PRADA, MINA, MONGIARDINO: INTERVIEW WITH FRANCESCO VEZZOLI ABOUT THE CITY OF MILAN

Italian artist Francesco Vezzoli's works range from the remake of Gore Vidal’s film Caligula featuring Cate Blanchett to one of Lady Gaga’s iconic performances on her pink Steinway & Sons piano. With an elegant craft in an array of mediums from film to painting to needlepoint embroidery, Vezzoli’s provocative work plays with themes of beauty, fame, and power with contemporary nuance. In his recent exhibition Teatro Romano, at MoMA PS1 in New York, Vezzoli, in his search of new beauty, traced back to his Italian roots. Working with a team of archaeologists, conservators, and polychrome specialists, Vezzoli painted five Roman busts in ways they would have been decorated — in vivid palettes of yellows, blues, reds, and greens, contrary to the white marble statuary people are used to seeing today. Subtle yet dramatic, Vezzoli’s work in Teatro Romano is beautiful and glamorous but in the ideals of a past time.

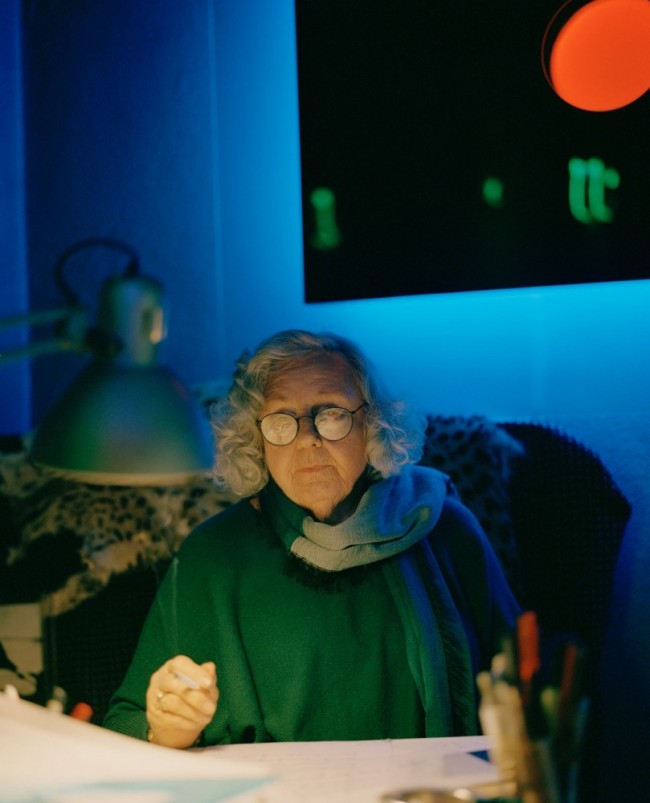

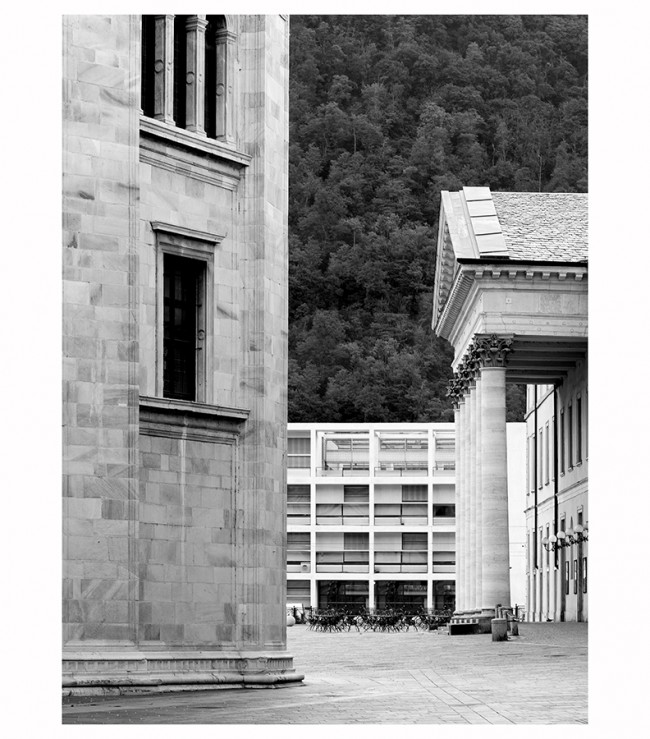

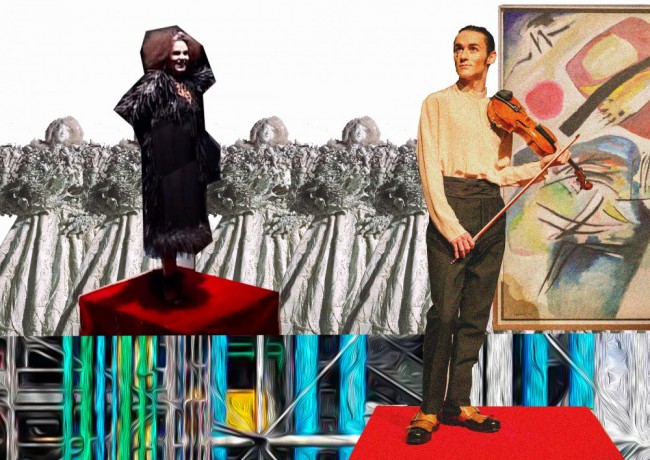

Vezzoli has also had a presence here at PIN–UP — we had the honor of the artist creating a metallic embroidery work, Hadrian Loved Antinous, as a tribute to New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp in PIN–UP 5, and a special story for our Milan Special in PIN–UP 16. In the feature, Vezzoli combined a portfolio of 14 personalities who all made a significant impact on the cultural identity of Milan, and in consequence on Italy as a whole. It’s a seemingly absurd and funny menagerie of luminaries, but for the artist Francesco Vezzoli they represent something quite serious: the cultural legacy of his adopted hometown, as well as its role in a nation currently in crisis. Born and bred in Brescia, 50 miles northeast of Milan, Vezzoli lived in London and Los Angeles for a number of years before moving back to the Lombard capital in 2010. Reached via Skype at his Castiglioni-designed studio near San Babila, the artist, whose work is no stranger to operatic oomph, muses on the city’s special brand of austerity, and on its capacity to fashion an Italian Dream.

So, Francesco, who are these people?

They are significant people in the history of culture in my nation, but there are of course plenty of those. The list could go on and on. The point for me was rather to discern a certain Milanese identity. And to do that you have to discuss the duplicity of identities reflected through the political, industrial, and social realities in Italy. If I were French or English, we wouldn’t even have this discussion, because in those countries there are just London and Paris, but in many countries there are two centers: New York and Los Angeles, Berlin and Munich, Beijing and Shanghai. In Italy, there is Milan, and there is Rome. Rome is the city of politicians, Milan is the city of industrialists. The weight of the aristocracy in Milan is zero, the influence of aristocratic families in Rome is enormous. In Rome you have the weight of the religious hierarchy, something that in Milan does not exist. Milan is a city where there is no room for decadence, there is no room for political games, there is mostly room for hard work.

That’s hardly news, though — everybody knows Milan is a rich city where people work very hard.

Well, you may think it’s a very banal and simplistic way of describing things, but this is a very serious topic: Italy is going through an enormous crisis, and more than ever we’re experiencing a dichotomy between the people who are working hard all over Italy, and Rome, which is doing a bad job administering all that hard work. But I’m not a businessman, so it’s not the business aspect but rather the moral qualities that I’d like to focus on. And I think the emotional identity of Milan is rooted in commitment and in modernity, whether in art, design, or fashion. Take two of the most obvious examples of Milanese artists, Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni: their courage was extreme and their art may still be considered more radical than most of what we see today. And I think the sense of freedom in their work comes from a sense of restraint. There is an important historic lineage in Milan, but the weight of history is not overbearing, so there is, and always has been, a certain freedom here.

Restraint isn’t a characteristic I would normally associate with either Maria Callas or Gianni Versace.

Well, but in a way they are the perfect example of what the Milanese identity is. They were both from very classic societies — Callas from Greece, Versace from Calabria — and they were both great baroque divas. But they came here because they felt compelled by the seriousness of Milan, and to rein in their decadence, to perfect their exoticism into a global persona, a brand. But what’s interesting is that most of these people came to Milan because it was the global stage for Italian Modernism. They were drawn to the city because it was the place where their instinct, their sensibilities could be understood, amplified, and they saw it as a ground upon which they could build their dreams. And in the process they became more Milanese than ever, ending up embodying the quintessential Milanese style.

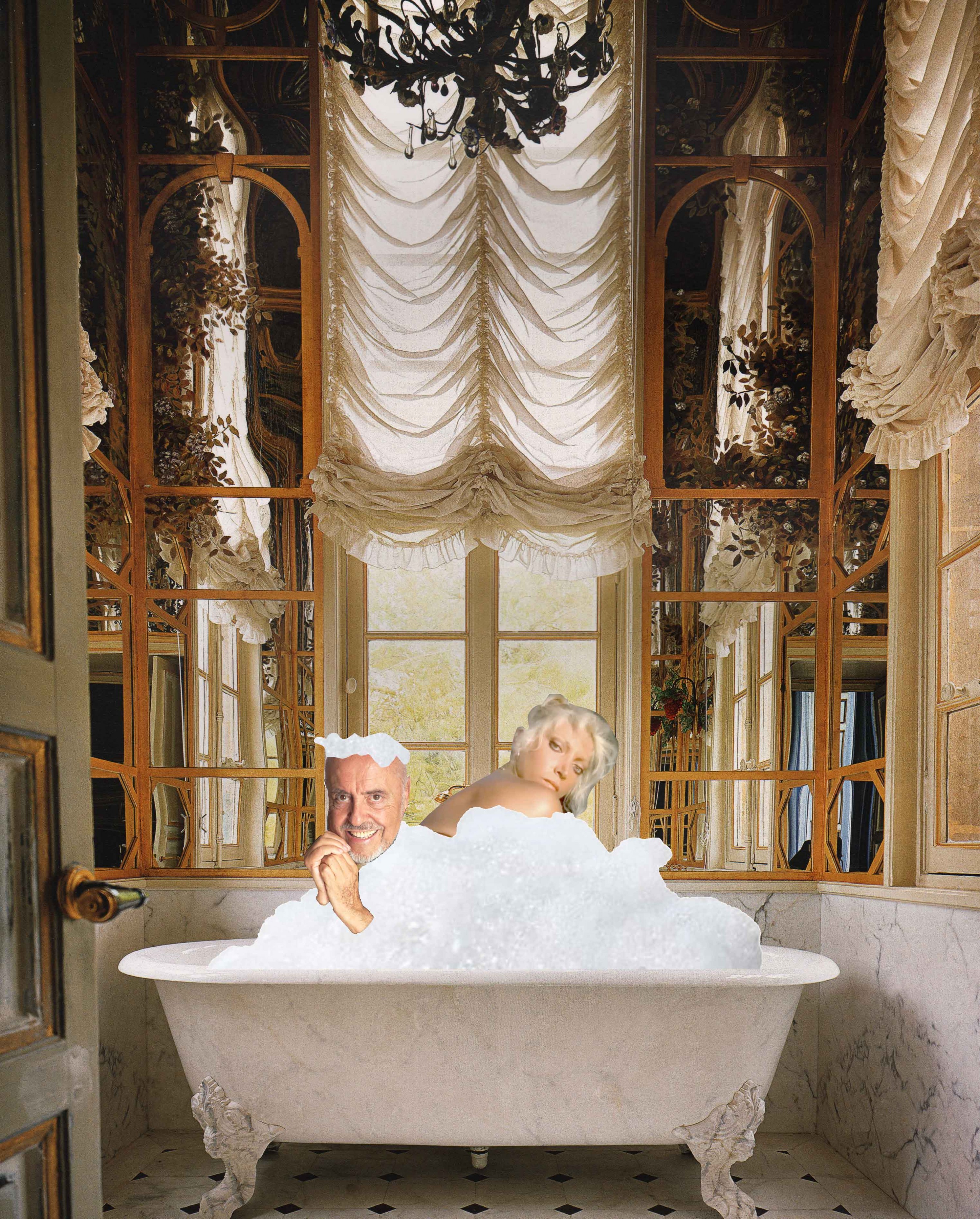

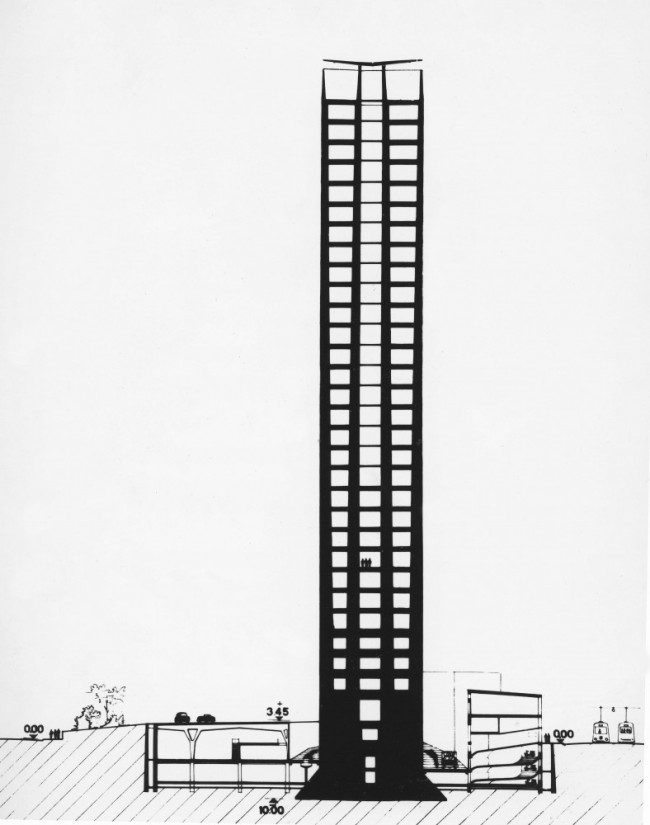

Speaking of style, what about Renzo Mongiardino, the interior decorator famously known for his lavish interiors, and whose work is the backdrop for all the couples in this story?

Well, that’s just another layer of complexity. Mongiardino established his offices in Milan — he was from Genoa, originally — but in order to gain success he had to go somewhere else. His style was decadent, it was anti-Modernist, it was hyper-decorative, all the things that the Milanese elite abhorred. Even Berlusconi, back in the 80s, wouldn’t let Mongiardino decorate his house. He was too sophisticated, too camp, too honest. So instead Mongiardino went to Hollywood, New York, eventually even Rome, where he worked for Valentino.

After living in London and L.A., why did you decide to move back to Milan?

I chose to come back to Milan to be closer to my family. But, more importantly, because of the city’s cultural heritage. I’m not talking about the 15th, 16th, or 17th centuries, I’m talking about now, or about the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. I’m talking about a city that for a relatively small amount of wealth — compared to New York, L.A., or London — has produced so many unbelievably relevant cultural figures, many of which are still growing now. Italy is suffering so much pain, facing so many problems, and experiencing such a level of humiliation compared to its past glory. Rome is without any doubt the most beautiful city in the world, it has the most amazing examples of art and architecture of almost every century in history. But if you try to produce your fantasies in Rome, you will be haunted by the unbearable weight of history. Milan is still a city where you can dream a dream, and actually produce it. In Rome those dreams may very quickly turn into nightmares.

Artwork byFrancesco Vezzoli. Special thanks to Gioele Amaro.