INTERVIEW: Design Studio Formafantasma On Their Material Investigations And Return To Italy

Where do things come from? Where do they go when we’re finished with them? Whether it’s studying computer detritus, volcano ash, or forest ecosystems, research-based design studio Formafantasma melds the poetic and analytic in their material investigations. Though their studies often inform the production of some very beautiful (and functional) pieces, the Italian duo — Simone Farresin from Vicenza and Sicilian Andrea Trimarchi — eschews the object cult of design. Since founding their studio in 2009, they’ve brought a unique perspective to the design world, and their signature mix of artfulness and advocacy was on full view last year with their most impressive exhibition to date, Cambio, at London’s Serpentine Galleries, simultaneously a love letter to trees and an ode to mindfulness, as well as a probing examination of the timber industry. Based in the Netherlands for more than a decade, where they set up their studio after graduating from the Design Academy Eindhoven, the duo is returning to Italy this year, establishing their practice for the first time in Milan, arguably the capital of European design. Serpentine artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist reconnected with the pair to discuss their recent homecoming, their new role at Artek, and their expansive approach to using design as an agent of social transformation.

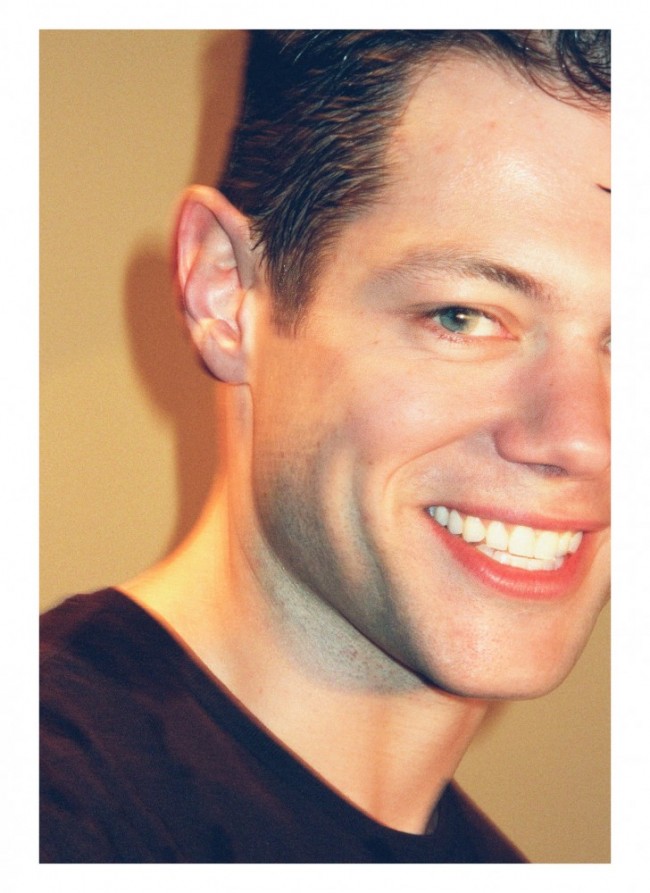

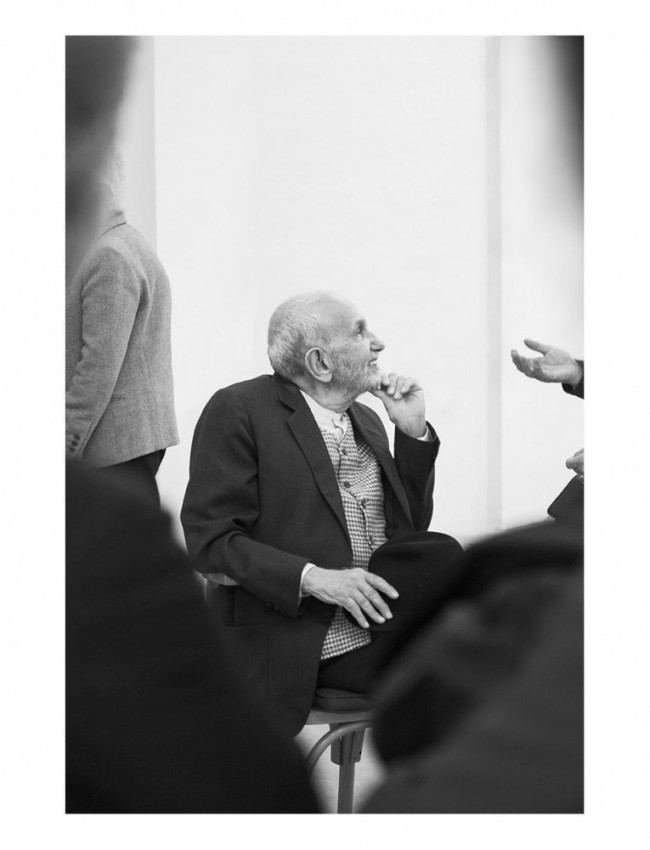

Simone Farresin and Andrea Trimarchi photographed by Bea De Giacomo for PIN–UP Magazine.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: You took the big decision to move to Milan from Amsterdam. It’s a homecoming after many years of exile. It would be great to begin with that: le retour à Milan. What prompted it? Is Milano again the caffeine of Europe?

Simone Farresin: To be honest, we really avoided Milan for many years. But we felt it was the right moment to come back. Holland was a fantastic chapter, a bit of an exile. We felt that. We never learned Dutch. Of course, that was our fault. We never felt we belonged there, but that was the great part obviously, because both in Holland and Italy, they are all about Dutch design/Italian design. We hate nationalism in design. We think it’s a cheap branding strategy. We’re not interested in that, so we escaped that definition. People didn’t know where to place us because we were Italians living in Holland. Now that we’re back in Milan we will not be overruled by all the cocktails and aperitivi. We’ll just keep on working and following our path.

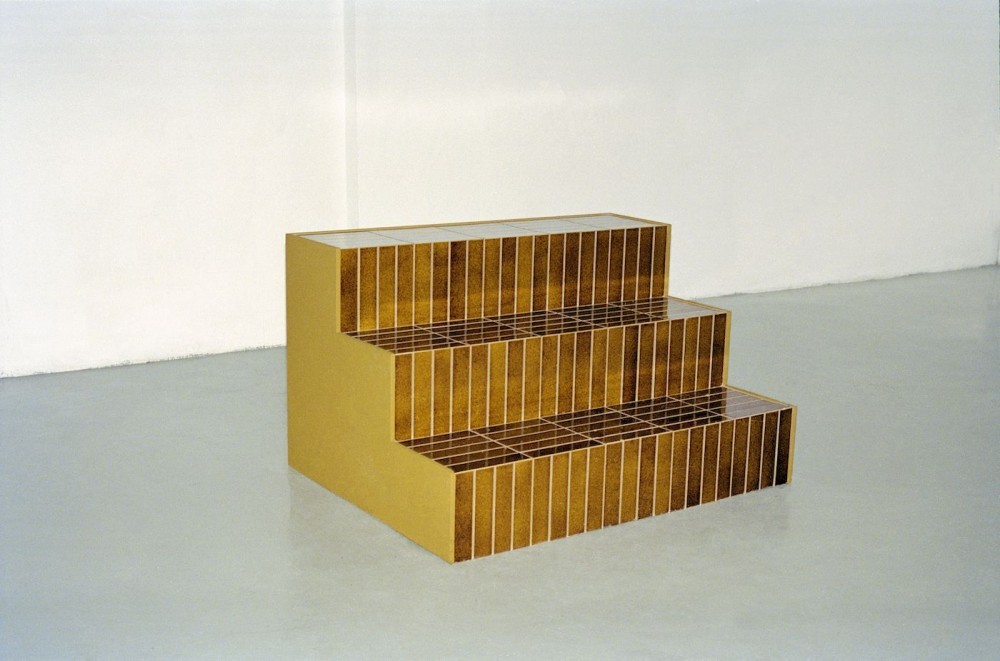

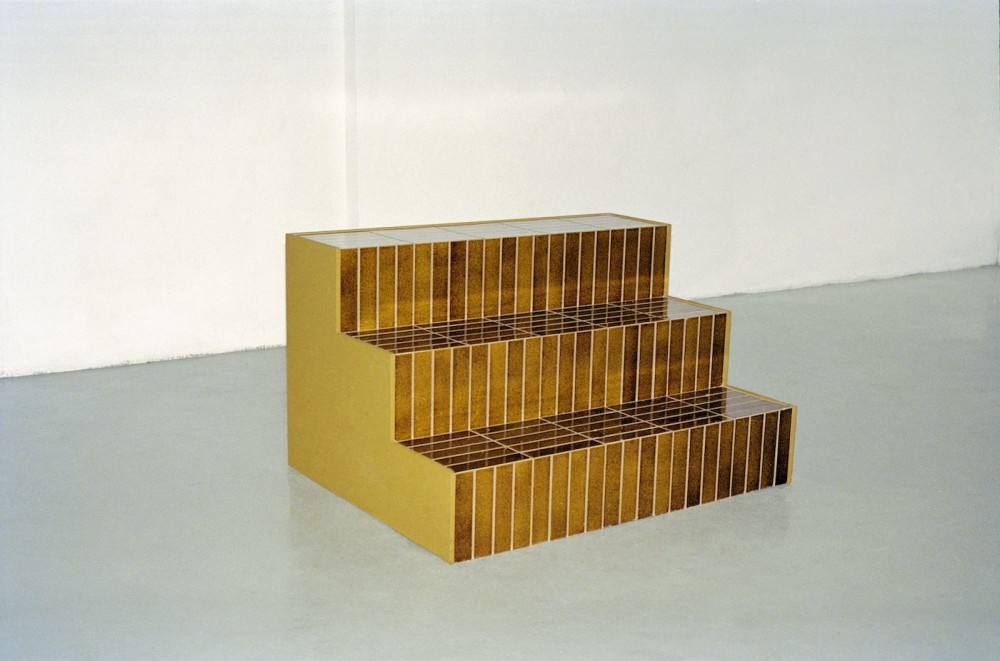

Formafantasma Ore Streams cabinet (2017–19); clear glass, digital print on aluminum computer cases.

In terms of work, it’s been an interesting moment because you have an anniversary. Ten years, but in a way it seems like 20 years, because it’s so much work. What are your favorites among the amazing inventions you have made?

Andrea Trimarchi: The straw brooms we designed for Autarky (2010). That is one of our best projects, I think. It’s very Enzo Mari. A broom is one of the simplest and most functional objects that exist in the world. It’s like a gesture, wrapping some straw around a stick.

SF: I say Botanica (2011). I still remember when we did those pieces. We thought they looked so weird. It’s interesting when you are surprised by your own work. You know where you start but you don’t know the ending. That’s what keeps you thrilled.

AT: Also the research we did with lava for De Natura Fossilium (2014). It was an alchemical process, almost primordial. You go to a foundry, you melt stone, and it becomes glass. They were cryptic objects we didn’t even design. They were coming out of the mold without us even thinking about them. That was a very exciting process.

SF: The recent work we are proudest of is what we did for Ore Streams (2017–19) and of course Cambio (2020). They go in a direction that is more like what we hope our next ten years will be.

Let’s talk about Cambio. It was an extraordinary process to work with you on this exhibition. The exhibition made me think of a proverb told to me by the legendary photographer James Barnor: “A civilization flourishes when people plant trees under which they themselves will never sit.” It made me think of Cambio with its long-durational dimension.

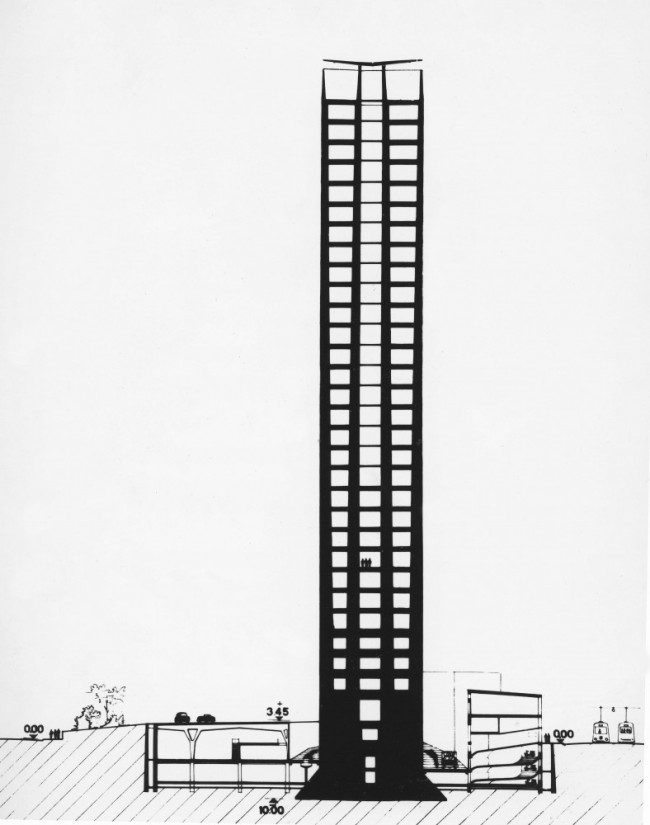

Exhibition view of Formafantasma's Cambio in Serpentine Galleries's North Gallery. The archive of lost forests.

SF: For us, time and duration are central. Looking at design and the materials we use daily, we can think how long it takes for a tree to grow, or for minerals to form on the planet. If you take this into account, the production time suddenly seems irrelevant. It’s about the growing of an ecosystem. If we designers start considering this, we can really develop the moral thinking that’s needed. It’s a huge problem in design: people always think of short-term solutions and results. There are different ways in which we are trying not to think short-term. One is like what we did at the Serpentine: we took almost two years to build the exhibition. Also, not consider- ing it the end of a beginning, but to expand it as much as possible, both in the format we use — online content, exhibition, catalogue — and by making it part of the educational curriculum of the GEO—DESIGN department at the Design Academy Eindhoven. Contributing to education is important to us. Our thinking is often more radical than what we do, because our design is mediated by the commissions we receive. We think education can help us share some of our ideas and questions with a generation that will outlive us physically and surpass us with its own ideas. So thinking about time in design includes thinking about education. We are limited by what little we can do in one generation, but if we work with others, they can contribute to achieving things that we cannot at this moment. When we create a body of independent work like Cambio or Ore Streams, it is often supported by institutions. We do not see this as the end, but as an opportunity to show how our thinking could be applied. Recently, the Finnish company Artek generously opened its doors to us, to look at what they do and see how our thinking can continue within the way they work. We really care about applying what we look into, not have it just be an intellectual statement in a museum. Mind you, there is nothing wrong with intellectual statements. But, for us, this is a moment where we have to take action, especially because we can. The good thing about being designers is that we can speculate, but we can also take action, and this is our position.

Formafantasma, Cambio (2020); video still.

To take action in a context of “emergency,” to quote our friends Alice Rawsthorn and Paola Antonelli.

SF: Absolutely. We are in an emergency situation. Especially after COVID, we will need to reconstruct again. But it is also an exciting moment to be alive and working. The best design was developed after World War II, because there was a need for reconstruction. Design can heal broken relationships with the environment and society.

Your work at the Serpentine Galleries in London all began with a tree. You made furniture from a single tree knocked down by a storm in Val di Fiemme, Italy. You then added archives from Kew Gardens and several other archives about timber history, and you presented research. As a highlight, you presented the visitor with a 13-minute video showing how the world is experienced from the perspective of a tree, with a monologue written by the philosopher and botanist Emanuele Coccia. In his new book Correspondences, Tim Ingold says we need to write letters to trees, because it creates empathy. In my experience working with you on the exhibition Cambio, with the curator Rebecca Lewin and the team, there was empathy.

Cambio exhibition view. On the Governance of forests. Serpentine Galleries, West Gallery.

SF: It was a generous process on a human level. We really enjoyed that. When you work, it is important that there is the human aspect in there. I agree that the most empathic element in the show is the contribution by Coccia for the film Quercus. For the show’s next destination, the Centro Pecci in Prato, we are adding two elements. One has to do with Kew Gardens, which is linked to the colonial past of the British Empire. Since Centro Pecci is in Italy, we felt obliged to reference the sometimes-forgotten history of Italian colonialism. We address how much Europe’s development was based on the exploitation of cultures and resources outside Europe. It is important to remember, especially in a country such as Italy, where the partisan forces fought Fascism, and Italians feel much less responsible for what happened in World War II than the Germans, for example. We need to be reminded that Benito Mussolini was elected. The other element added to the show is a story about the building of Florence. Ecosystems and the city are related. The walled city of Florence was built in the Renaissance with the use of one species of tree, the white fir, from an area named Vallombrosa. There is a monastery there. The monks introduced the tree in plantations to allow the city to grow. Now there is a sylvicultural museum, basically a large area of the forest where these trees are still planted, where they are growing. They are meant to live there for centuries so they can become a big as the trees that were used in the past to build the city of Florence. It’s a small story, but it illustrates the relationship between cities and the ecosystem. With the sylvicultural museum in place, if something happens to any of the buildings in Florence, they can be reconstructed with the same kind of living creatures that existed in the past. The meaning behind this is, if we lose our ecosystem, we lose our culture. The two are indivisible.

Formafantasma, Cambio (2020); video still.

What forms the legacy of a designer?

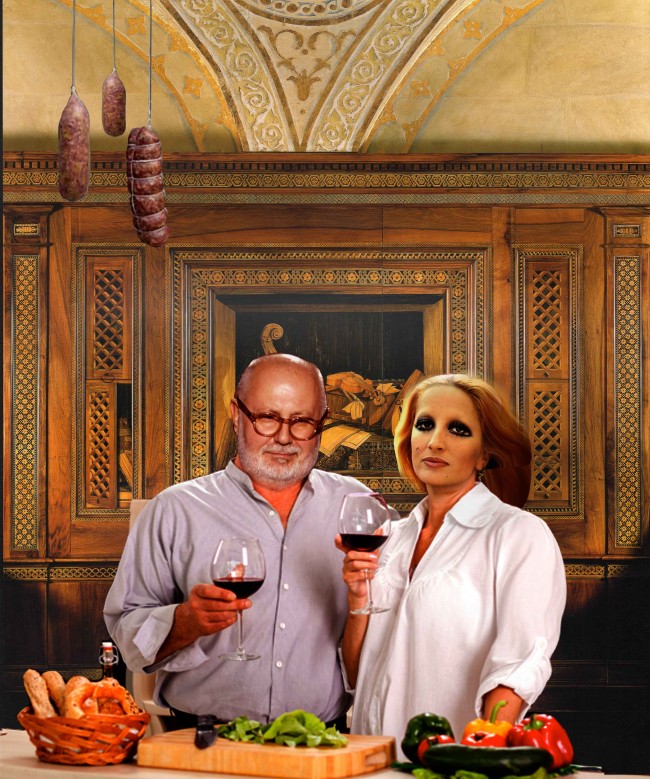

SF: I was quite young when I became interested in design. I loved the work of Enzo Mari and Ettore Sottsass, as different as they are. We did not own any of their objects, but I did not need to own any of their objects. I think that was their legacy. There is a thinking behind what they did that went beyond the objects. Objects testify to a way of thinking. In design, the object too often takes center stage. When you asked us to work on Cambio, a liberating thing for us was that you said that you were not interested in making an exhibition of objects, but rather about designers’ way of thinking, a show that is their manifesto. Of course the object is important, especially for museums, which are responsible for legacy. Some of our most research-based work could only exist in a museum through the object. Museums still have traditional ways of archiving design. The majority of design museums want stuff — furniture, lights, etc. The MoMA under Paola Antonelli has been forward thinking in this regard. Still, the object is needed for the archive of ideas. The ideas survive and become timeless when they transcend the stuff itself, the materiality. Mari’s objects vehiculate his ideas. What I learned from him is not his materials, but his choices. The interviews and writings of Mari, Sottsass, and Alessandro Mendini — speaking of Milanese designers! — are their real legacy.

How do you archive your work?

SF: In our first ten years, we were not good at archiving. We are starting now to do it properly, categorizing and all. We’ve been through other designers’ archives, like Roberto Sambonet’s, Enzo Mari’s, and Pier Luigi Nervi’s at the MAXXI in Rome. The Nervi archive stressed us out, because it was so incredibly well done. It made us realize how sloppy we are. Most things from our past ten years are already lost. I don’t think we have our own Autoprogettazione yet, but with our latest work, which is more research based, we are trying to make a good selection of the research we do available for others. It’s not exactly a way to make our work survive, but it gives others the information we collected so that they can build upon it. This makes design go beyond being authorial. Design is obsessed with who did what. The most important thing to archive is information, interviews, the knowledge you acquire.

Formafantasma’s ExCinere volcanic ash-glazed porcelain tiles for Dzek. Photographed by Adrianna Glaviano for PIN–UP.

Then there are your books. How do you see books with respect to legacy?

SF: The Cambio catalogue is not really a catalogue, it’s a book. It was extremely important to have it, and important to work with the Dutch graphic designer Joost Grootens. The book was important because we all face the limitations of the medium we work with. Of course the exhibition is an amazing way of reaching people and doing things in space, but that’s a spatial experience, and you cannot convey everything from there. The book gives another dimension to our work, a long-lasting one. Paper is proving to be longer lasting than digital tools.

You thematized the idea of paper in the Cambio catalogue, and how paper is being used in a more responsible way.

SF: Yes. And now we are expanding our research to forestry in Finland, for Artek. We looked at the ecosystem first. We saw how the paper industry totally influenced forestry there. But you need to make choices. I will always be ready to cut down a tree to print a decent book. There’s nothing wrong with materials, not even plastic — the question is what you do with them. When making the Cambio catalogue, we wanted to address the materiality of it, so we tried to make the issue more transparent. We asked an institute in Germany about some of the paper samples Grootens used for the book, and sought to mention which kind of trees were used. This is not necessarily a solution, but it’s an attempt to make people more empathic towards the materials that surround us. The act of leafing through a book is a way of leafing through an ecosystem. We are fascinated by the idea that objects recreate different planets. We see planet Earth as the Blue Marble, but an iPhone is a completely different planet — shifted materials, minerals, plants, and animals from all over the world, assembled in a different form.

Simone Farresin and Andrea Trimarchi photographed by Bea De Giacomo for PIN–UP Magazine.

Something that has been widely discussed since the beginning of the pandemic is the emphasis on the local. Are you interested in that? Édouard Glissant said we are living in a world of globalization, and though there have been previous globalizing movements, none have been as violent as the current one. Glissant said we need to resist homogenized globalization, while simultaneously also needing to resist new nationalisms and new localisms, which refuse the global dialogue — something that has been exacerbated through the current crisis. Glissant said we need to ask ourselves how we can be local without being localists. How do you feel about these discussions that art and design should be more local?

SF: We have tried to explore the issue of the local many times in our work — also how on a political level it can be dangerous. Design has played an important role in the development of national identities. Think of how often the idea of local craft is used to represent local identity. It is weaponized to represent an immutable entity. UNESCO used to give strict directives to citizens on how to maintain what it thought was their heritage. Then it realized how dangerous it was. Our project ExCinere (2019) looked into the possibility of using volcanic ash from the Etna volcano in Sicily to develop glazes for tiles. Why would we do that? Many glazes for tiles are made with mined minerals. We wanted to see what kind of formal outcome we would obtain by rooting the process in a specific locality.

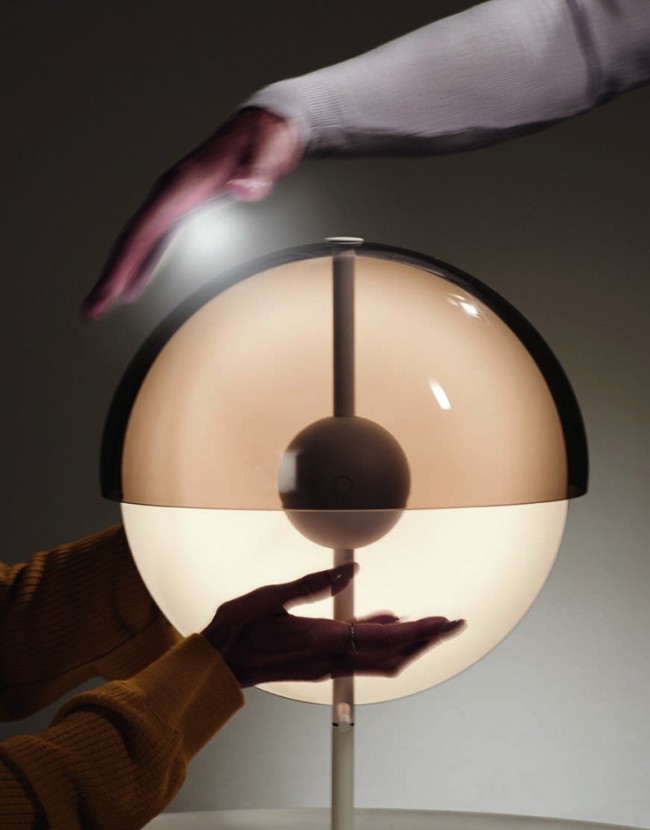

When I visited the late Achille Castiglioni, he showed me a light switch and a spoon, saying they were two of his favorite works. He said design should not be luxury goods, but for everyone. It should reach millions of people if we want to change the world.

SF: I completely disagree with Castiglioni. The switch and the spoon are not his best works. I don’t think ownership is a way of building legacy. I don’t think his work reached people because they could afford it. Actually, those works are probably the most irrelevant he made. He subscribed to the Modernist, idealistic idea that design could reach everyone, but those “everyones” are living in a small part of the world, and those switches probably ended up polluting the oceans. His is an old utopia we shouldn’t consider anymore — the idea of democratic design is utter nonsense in our times. It’s still used by huge companies selling T-shirts for 2 euros at the expense of the environment and the workers. We don’t believe design should be elitist, but the best design to me is not because I bought it, but because I engaged with the designer’s ideas. I never bought an object by Enzo Mari until recently, but I did engage with his ideas.

Formafantasma, De Narura Fossilium salina detail (2013); mouth blown lava, casted lava, lava rock, textile, Murano glass.

What did you buy?

SF: The Java box by Danese. We also have the Putrella centerpiece and we even built our own Autoprogettazione. (Laughs.) But I don’t believe in ownership. The great contribution a designer gives is on a cultural level. Sometimes people say our work is elitist because not many people can own it. They ask how we could reach a bigger public. Well, we hope to reach people with our ideas most of all. With Artek, we are not working on a product, but at a systemic level — we’re studying the supply-chain management, where the material goes at the end of its life cycle. This requires restructuring the company in a long-term way. It’s easy with Artek, because they are already engaged with these subjects. They ask the right questions. This is finally the kind of relation we wanted. They came to us after they saw Cambio.

-

Formafantasma, Cambio (2020); video still.

-

Formafantasma, Cambio (2020); video still.

-

Formafantasma, Cambio (2020); video still.

Where do you see the future of design?

SF: We are lucky to be operating at this moment in time, because through social media and other platforms we have the agency to reach people beyond the product, which is a privilege the previous generation didn’t have. As for the economy, it’s the elephant in the room. When we were working on Ore Streams, trying to come up with pragmatic strategies to make electronic objects more repairable and recyclable, we knew it was a short-term strategy, a way to act in the system at this moment, but not a long-term solution. Long term is only if we rethink the economy, if we establish new business models. Ecology cannot exist based on growth. People are critical of capitalism, but it’s the only utopia we humans have managed to construct. We built an economy around perennial growth, like a Pantagruel that keeps on eating and devouring the world. It’s fascinating and exciting, but extremely problematic. What we can do on that level, I don’t know. When we work with our students at GEO—DESIGN in Eindhoven, we hear them calling these ideas into question, so we definitely have faith that the generation after ours will be more radical than we are. Probably because they didn’t grow up in the 1980s like we did. They will be able to put into practice some of the ideas that are just now emerging.

Interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist.

Portraits by Bea de Giacomo.

Work images courtesy Formafantasma.