INTERVIEW: Miles Gertler On Funerals, Fitness, and the Design of the Body

Although he only graduated from Princeton School of Architecture in 2016, Toronto-based Miles Gertler has already proved himself a voice of the future with his accelerated accomplishments and sci-fi speculations. Together with former classmate Igor Bragado, Gertler is one half of the itinerant art-and-design research practice Common Accounts. Preoccupied with the design of the body, in particular through cosmetics, self-optimization, and — paradoxically — death, they’ve designed a prototype for a Korean funeral home where the body can be liquified into fertilizer for a memorial garden, as well as hybrid online/in-house platforms at Sephora’s Shanghai flagship store. In addition to lecturing at Harvard and teaching at Cornell, Gertler and Bragado have shown work at the Academia de España in Rome, the Istanbul Design Biennial, and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. Gertler also practices independently as a visual artist, creating architectural para-fictions that often collapse past, present, and future. PIN–UP paired the Canadian creator with Swiss super-curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, who asked him about his research-based architectural practice and how make-up tutorials, gym selfies, and emerging virtual afterlife rituals are all linked to our inability to face our own mortality.

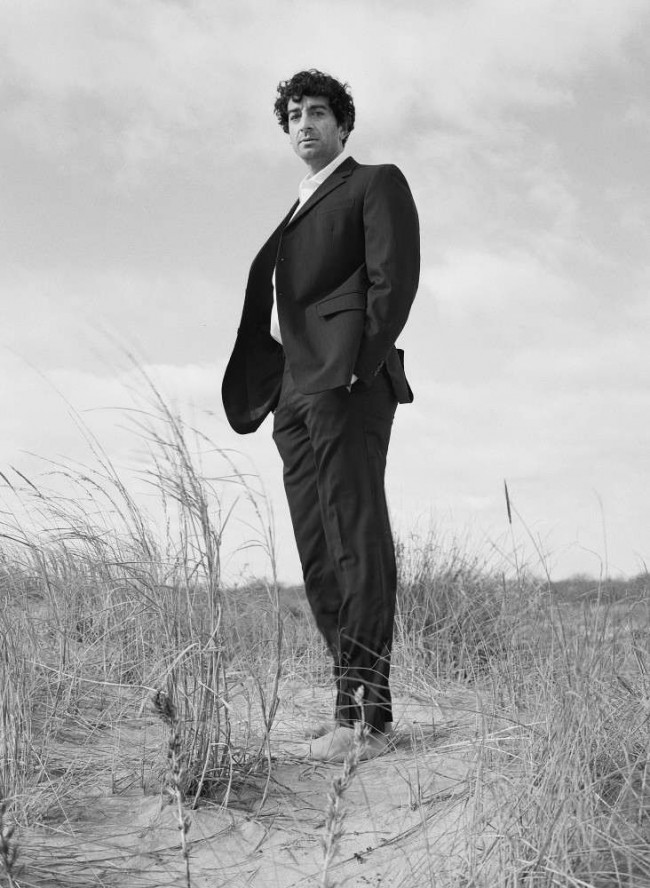

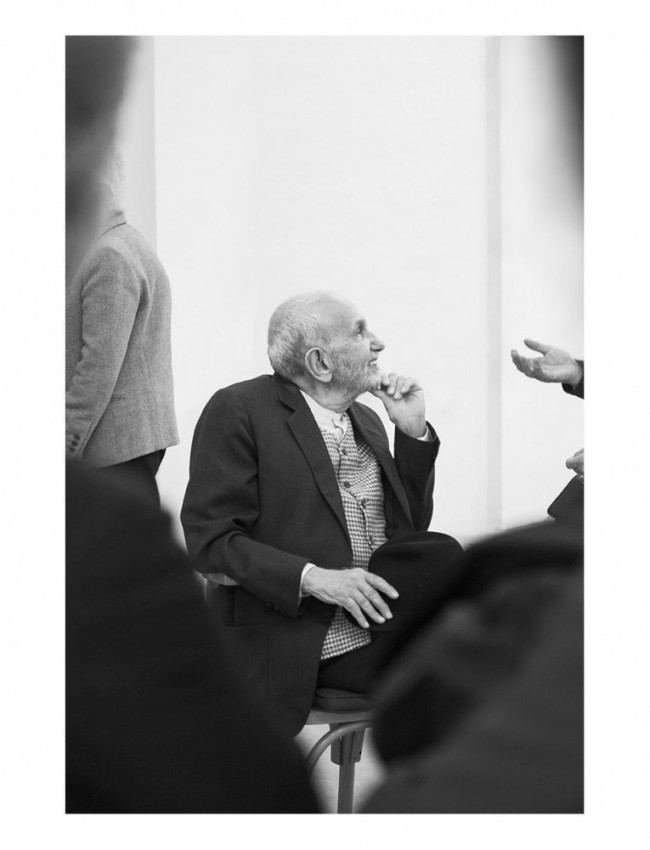

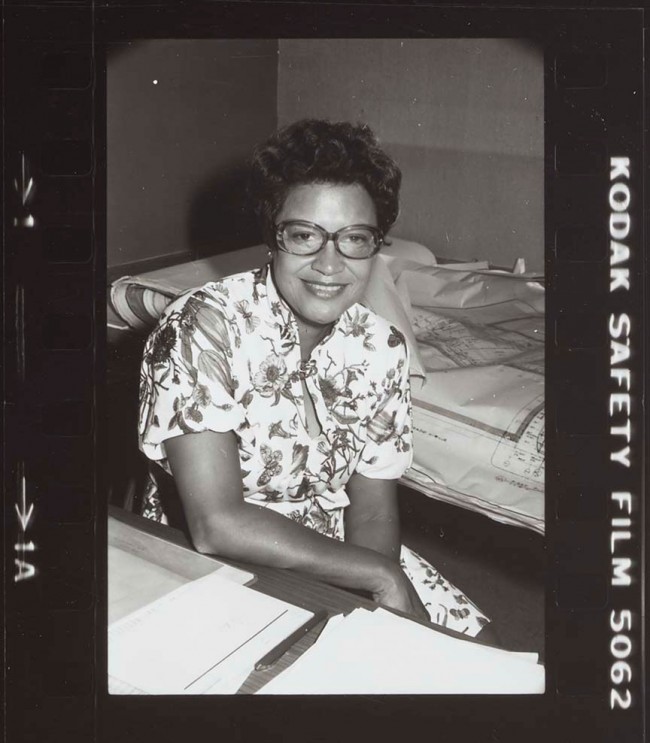

Miles Gertler shot by Rémi Lamandé for PIN–UP.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: I think it’s always very important to talk about unrealized projects so that their potential can be realized in the future. Can you describe your proposal for the Canadian Pavilion at the 2020 Venice Architecture Biennale?

Miles Gertler: Our proposal was called After Life. We were interested in looking at some of the unexpected conditions and behaviors that we felt were being initiated in the Anthropocene, in the face of climate change and other big hazards society is facing. We found that, perhaps somewhat paradoxically in this moment of the greatest existential threats to humanity, humans were spending more time than ever on the design of themselves and lavishing attention on the body, particularly through fitness and through optimizing and upgrading the body. Perhaps it's a means of producing a lifeboat or a placebo — a lifeboat in the sense of your own personal escape pod or survival bunker to avoid the most cataclysmic consequences of climate change, a figure of survivalist aesthetics around the body if you will; and a placebo in the sense of a therapy that helps overcome the existential anxiety engendered by the threat of environmental collapse. We felt that this was something that architecture should be looking at because it’s already one of the ways in which more people are engaging with design on a daily basis, and we’d be remiss not to examine it. Although this was for the Canadian Pavilion, we very much feel that this is a global issue, so we had an incredible team of people, in architecture and beyond, posted all around the world.

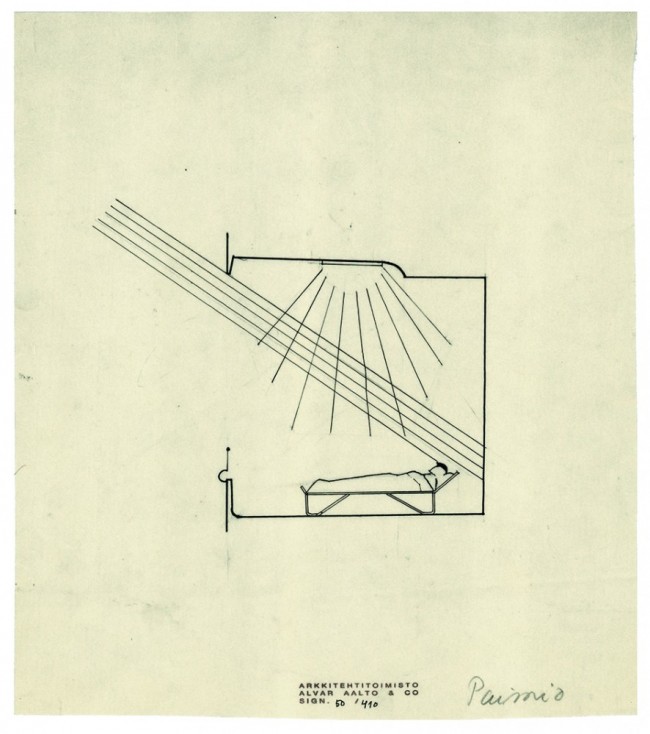

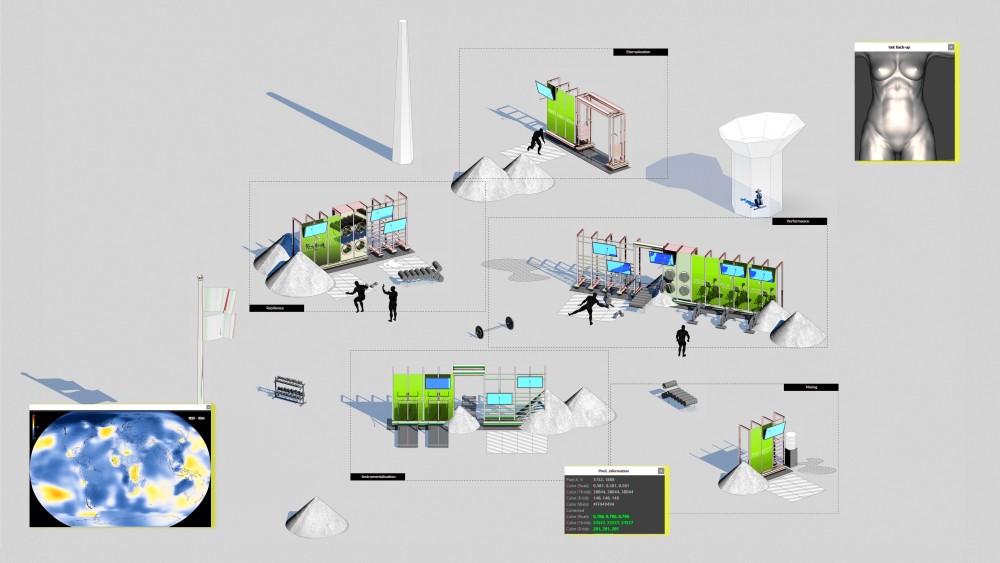

What would the After Life pavilion have looked like?

We were interested in the Bauhaus fascination with the gym as a paragon of public space, so the idea was to produce a series of fit-ness infrastructures that would at first glance look like the sorts of technologies and ephemera you would find in a gym — TVs, laundry machines, watercoolers — but which in fact were all demonstrating subtle ways in which the body is now being designed. For instance, a watercooler with synthesized tyrosine in it, which simulates the neural responses of engagement with social media, basically trying to simulate the neuroscience of the gym selfie. Also videos, which might at first glance look like the newscasts or shopping programs you see at the gym, but which on closer inspection turn out to be presenting something a little bit off, something more akin to, or at least more attuned to, self-design. There was the idea of hiring a cast of performers to exercise the entire time.

After Life (2018), a proposal for the Canadian Pavilion at the 2020 Venice Architecture Biennale by Common Accounts, the architecture and research group Miles Gertler founded with Igor Bragado. Through After Life, Common Accounts intended to subvert the spatial tropes of gyms — treadmills, TVs, laundry machines, and watercoolers — and other environments of self-optimization to interrogate how existential uncertainty has triggered humans spending more time on the design of the body through fitness and beautification.

(Erwin) Panofsky famously said that we invent the future out of fragments from the past. What kind of architects, designers, or artists from the past inspire your projects?

It was impossible for us not to consider OMA’s Casa Palestra installation at the 1986 Milan Triennale in this context. But we were also interested in the discourse created around the idea of the gym by much earlier figures, like Hannes Meyer from the Bauhaus. Many of our references also come from beyond architecture. We’re fascinated, for instance, by the way the artist Lu Yang, in Lu Yang Delusional Mandala (2015), is constructing a designed self very explicitly through her video work, in this case as a genderless, digitally-rendered humanoid undergoing a rapid aging process.

Hans Hollein also comes to my mind.

Oh my god, yes! How can I even talk about this without talking about Hans Hollein? We’re especially interested in the discourse around MAN TransFORMS, the 1976 exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt in New York he put on with Lisa Taylor. Also, as an image-maker, Hollein is a really important reference for us. In fact, Igor and I wanted to do sunglasses for Common Accounts, because of Hollein’s amazing 1973 collection for American Optical Corp.

Another unrealized project! How did you come to architecture and design in the first place? Was there an epiphany or a trigger?

It’s something I wanted to do since high school. Already I was drawing. But what I thought design was in high school was not at all what it ended up being for me. I went to architecture school for undergrad and graduate degrees. My grandmother, though, was a sculptor, and…

What was her name?

Anita Gertler. Anita Birnbaum, originally. She came to sculpture in an interesting way. She was liberated from Auschwitz and then was sent to a temporary working program in London, where she began to work with clay as a dental assistant — she was making casts of teeth. It was when she came to Canada that she enrolled in school to study sculpture. So that sort of climate of sculpture and artistic production has always been around me.

Itaewon Chair is the first furniture from Common Accounts. A stool and small coffee table, it is welded in the manner of urban roadside barricades that populate the streets and laneways of Seoul. Set down across its surface, a hardcover book provides a flat tabletop. Laid open, the table’s tubes display the spread of your choice, or simply hold your place like a bookmark.

You studied at Princeton University School of Architecture, right?

Yeah, first at the University of Waterloo in Canada, and then at Princeton.

I’m curious about who your influences were at Princeton.

There were influential figures like Andrés Jaque, who has a fascinating ability to construct a language around each new project in a way that forms discourse. Or Michael Meredith, who taught a class that was designed as a vacuum — a productive vacuum where you could produce essentially anything, but it had to be physical. And then there was Beatriz Colomina. She and Mark Wigley were working on the (2016) Istanbul Biennial at the time, and they had this statement which has deeply informed our practice: “Every theory of design is always common to the theory of its own inhabitant and ideal occupant.” That makes it quite clear that the body is always a subject and site for design, which for Igor and me was an important part of the foundation of our practice Common Accounts.

How did the decision for you and Igor to collaborate come about?

He and I were in a studio together under Stan Allen, and we kept checking in on each other’s work and critiquing it, somewhat jealously I think. We were each interested in the work the other was producing, and we also started to develop language for each other’s projects. It became quite clear by the end of that first semester that we needed to work together. And then, for our remaining time there, we developed projects which would ultimately become our thesis and the foundation of our practice — looking at the design of death and the body, and the way it navigates spaces both online and IRL, and the way that death and fitness and these other tropes of our practice are situated on this spectrum of healing and dying, construction and destruction of the body.

I’m curious about the constant theme of death in your work. Leon Golub once told me, “Death is a dull fact.” Which is a good definition of death. At the same time, we live in a culture where death is very invisible.

Yes, it’s this invisibility of death that we’re interested in. We think that architecture has not taken death seriously, or considered it deeply, for about 50 years — not really since Postmodernism. And we felt that even the Postmodernists were considering death only from the perspective of metaphysics and poetics, while we were interested in the material business as well. What do you do with a body that’s decomposing? How do you consider temperature and preservation? And, especially now with today’s environmental issues, can we continue to burn bodies? Can we continue to put them in the ground filled with embalming fluids? And so we started to look at the material business of death, and found that the death-care industry was a fascinating place where we couldn’t propose anything stranger than what was already happening.

Common Accounts’ Refresh, Renew continues their line of research on the subject of architecture’s role in the intersection of death and daily-life. If the cemetery and the mausoleum are no longer the exclusive spaces for the funeral ever since the arrival of social media a little over a decade ago, this alteration the funerary social spheres has multiplied the spaces through which ceremony is channelled.

What were some of your the most exciting findings?

Take the problematic issue of a dead person’s social media account, for example. There was a man named John Berlin who lived in Missouri and whose son died unexpectedly at the age of 21. Shortly after his son’s death, the father began producing YouTube fitness videos. We found that a lot of people who encounter the unexpected death of a loved one turn to fitness to distance their own selves from mortality. The father took it very seriously, not only transforming his body but also becoming younger looking, in a sort of strange memorial to his lost son. He also started to record his workouts in his home space, and eventually professionalized the gym. And so his mirrors and fitness equipment started to displace the photos of his deceased son, and the sort of memorial dressings of the room were slowly turned into a gym. And this was all seen through the web camera on his computer. And over a period of a few years…

Is this a real story? Because it sounds like fiction.

It’s real. And it gets weirder. At some point Facebook puts out his son’s “Look Back” video, which summarizes the greatest hits of your likes, photos, and friends’ messages. Because he and his son weren’t friends on Facebook, the father realized he couldn’t watch his son’s “Look Back” video. He became increasingly frustrated and recorded a plea on YouTube directed at Mark Zuckerberg to let him see it. The thing went viral and CNN and all these big news agencies started covering the story. Eventually Zuckerberg called him and granted him his request. It’s a funny story but it’s also super problematic because it brings up all sorts of ethical issues around the digital material of people who no longer have a say in how it’s regulated or distributed.

Digital immortality! My friend Hélène Cixous, the French visionary writer, has this conviction that cemeteries are very barbaric cities. That we need to pay more attention to cemeteries and create a more dignified environment, and consider them with the same attention that we pay to cities for the living. Would you agree with Cixous? And have you designed cemeteries?

We found that there was a tradition in many cultures in other times to have a nearness to death. And in our early projects on the subject, we always said that with all this death, the city should feel more alive than ever. So for Three Ordinary Funerals, our installation for the 2017 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, we built a prototypical funeral home.

-

For the 2017 Seoul International Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism Miles Gertler and Igor Bragado, who together form Common Accounts, created a prototypical funeral home for the virtual afterlife. Titled Three Ordinary Funerals, the project was staged in one of the South Korean capital’s traditional hanok villages and explored ideas of alternative technologies for the disposal of the human, such as alkaline hydrolysis, a technique in which the body is liquefied into a fertile solution, which can then be used

to fertilize a memorial garden. The project is now in the permanent collection at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul (MMCA). -

For the 2017 Seoul International Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism Miles Gertler and Igor Bragado, who together form Common Accounts, created a prototypical funeral home for the virtual afterlife. Titled Three Ordinary Funerals, the project was staged in one of the South Korean capital’s traditional hanok villages and explored ideas of alternative technologies for the disposal of the human, such as alkaline hydrolysis, a technique in which the body is liquefied into a fertile solution, which can then be used

to fertilize a memorial garden. The project is now in the permanent collection at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul (MMCA). -

For the 2017 Seoul International Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism Miles Gertler and Igor Bragado, who together form Common Accounts, created a prototypical funeral home for the virtual afterlife. Titled Three Ordinary Funerals, the project was staged in one of the South Korean capital’s traditional hanok villages and explored ideas of alternative technologies for the disposal of the human, such as alkaline hydrolysis, a technique in which the body is liquefied into a fertile solution, which can then be used

to fertilize a memorial garden. The project is now in the permanent collection at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul (MMCA).

Was it a digital funeral home? Or a physical one?

Both. But we primarily looked at new technologies for the disposal of the human. There is one new technology in particular called alkaline hydrolysis in which the body is liquefied into a fertile solution, which can then be used to fertilize a memorial garden. It’s touted as a green alternative to cremation because there is no carbon release through burning. It’s a technique that has long been used for the disposal of bodies of farm animals that pose a health hazard, or animals in scientific testing facilities. We found a Korean manufacturer and we produced a prototype for a funeral home in one of Seoul’s hanok villages whose houses are the traditional site of Confucian traditions like funerals and weddings. We had also produced a video, which simulated the uploading of the virtual material.

So you’ve also created and produced the actual rituals around this alternative funeral?

Yes. We worked in consultation with Korean experts and local curators to ensure it was done appropriately. What we found out is that Korea is one of the few places where the traditions around death have recently been up for redesign. For instance, in order to popularize cremation, the Korean government has embarked on an intense lobbying campaign over the past 20 years, putting pressure on TV producers to create more plots and episodes in which characters die in hospitals that handle death care and whose funerals take place in the new kinds of crematoria. As a result, attitudes have changed from 20 years ago, when nobody ever wanted to be cremated, to most Koreans now wanting it.

You mentioned earlier that there is a connection between your research on death rituals and your research about the cosmetic industry. Can you explain that jump?

Our interest in death came from looking at ways in which we design our bodies today. If we look at biological expiration as simply an inflection point between the design of the body in life through fitness and the documentation of that — for instance in photos and in selfies, and generally on social media — and the image of the body after death, we understood that death was another way and another space in which humans had the ability to design or reimagine themselves. And for us, that’s also cosmetics. Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley initiated the project. They knew our thesis and commissioned us to research the urbanism of plastic surgery in Seoul’s Gangnam district for the 2016 Istanbul Design Biennial. Furthermore, while we were in Seoul producing the prototypes for Three Ordinary Funerals, we were introduced to people who were working in the cosmetics and medical industries and who were consulting for Sephora. They were incredibly interested in how architecture might span the online and the in-store environment in similar ways, looking at the research we had done on John Berlin, death, and Facebook. And so, for them, this was actually a natural segue.

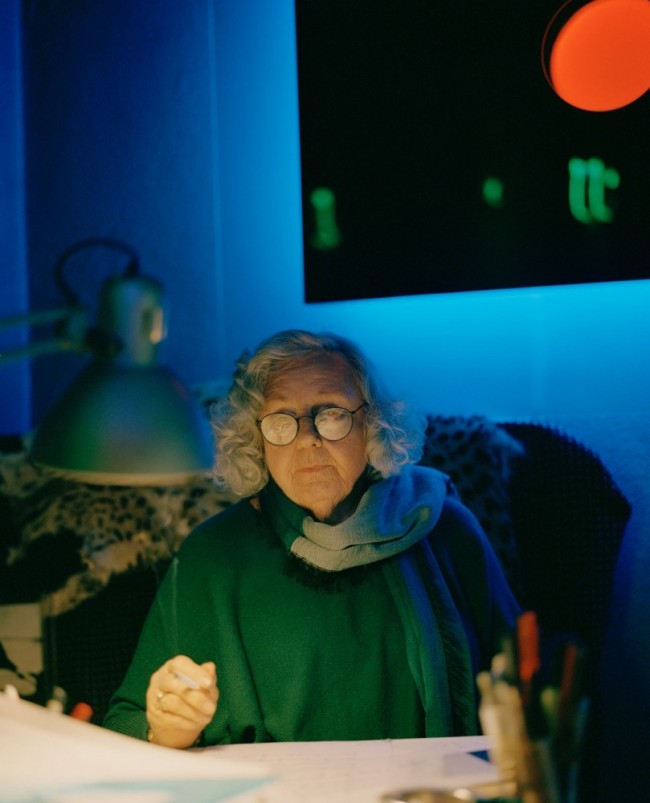

Miles Gertler shot by Rémi Lamandé for PIN–UP.

You’ve done several shows with Corkin gallery in Toronto, but they’re always under your own name, not Common Accounts. Can you tell us a little bit about that aspect of your practice?

For the past several years, independent from Common Accounts, I’ve been producing these architectural images which I think reach a completely different audience than our work as a collective. At first I was making mostly hand drawings, but then I started to translate them to the digital. When I was studying in Rome, in 2012, I worked on this catalogue of architectural possibilities in form that were sort of dropped into Mediterranean colonial-era photography. I made a Risograph book, only 100 copies, and at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale I gave them to anyone who seemed interested. One of the books fell into the hands of Jane Corkin, of Corkin Gallery in Toronto. The next day I had an email from her saying we should talk. So I started working on a show for the gallery, but my work with Igor on post-humanism started to inform the original images. The outcome was this series for the 2017 show Rare Item, where I was looking at these post-human pleasure gardens. These gardens reference botanical drawings from the early modern period. Also, in Toronto my boyfriend and I care for this tropical greenhouse of over 200 plants. It’s just one of those things that’s rubbed off on me.

So you have your own post-human pleasure garden?

In a way. Our studio is in the former gardener’s quarters — on the same site as the greenhouse but in a different building. We did a party in the greenhouse last year and the playwright Jeremy O. Harris came and did a performance there.

Jeremy’s so unusual for someone of your generation — playwrights and theater have become much less present in our culture.

Jeremy is someone I knew personally before I knew any of his work. But I started to hear about this play that he was developing, called Daddy. The set is a mid-century-Modern villa in Bel Air. The project was essentially about queering that space, not only through its inhabitation by gay men, but also by introducing black bodies that weren’t originally intended for this white, upper-class architecture. So instead of getting the outward-facing vista, the set put the audience in a place where it was confronting the villa — just like in David Hockney’s A Bigger Splash, looking across the pool back at the house. And in so doing, re-versing, queering that colonial gaze, turning back inward. I wrote an article about the set for the Avery Review.

Commissioned by the Spanish Academy in Rome, and installed in San Pietro in Montorio Square, Refresh, Renew proposes alternatives to the current funerary protocols for the channelling of ceremony both online and IRL. It manages the digital remains of a life lived online, matching the current multiplication of bodily images as they navigate online and persist after biological expiration.

What’s the role of writing in your practice? Especially when you and Igor write together.

It’s an exercise for us. We’re trying to ensure that the work maintains a critical perspective and also a radical foundation. We write together, which is the same way we produce projects — we pass files back and forth on a remote server. Igor and I are often apart. In fact, since we founded our practice, I don’t think we've lived in the same city. After Princeton, Igor was living in Seoul and I was living in Toronto. Now I’m living in Toronto but last year I was coming to New York half the time, and Igor and I were teaching at Cornell and Cooper Union. More recently he was in Rome for six months doing this project for the Academia de España, and currently he’s in Madrid. Neither of us is in Seoul but we’re doing a project for the Seoul Museum of Art opening next month, so we’ll be back there again. It’s a sort of itinerant mode of practice made possible by remote server. It’s now our second nature.

Well in a way it’s ironic that I’m sitting here today with you doing this interview. Because Ben Vickers (curator, activist, and Chief Technology Officer at the Serpentine Galleries) is currently working on this algorithm so that I’ll no longer have to do the interviews myself. Everything I’ve ever said and done is being fed into AI technology. Which also means that this might be one of the last interviews I do in person.

So you’re becoming a bot?

Yeah.

How do we know you’re not already a bot?

Exactly.

Interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist.

Portraits by Rémi Lamandé for PIN–UP. Work images courtesy Common Accounts.

Taken from PIN–UP 27, Fall Winter 2019/20.