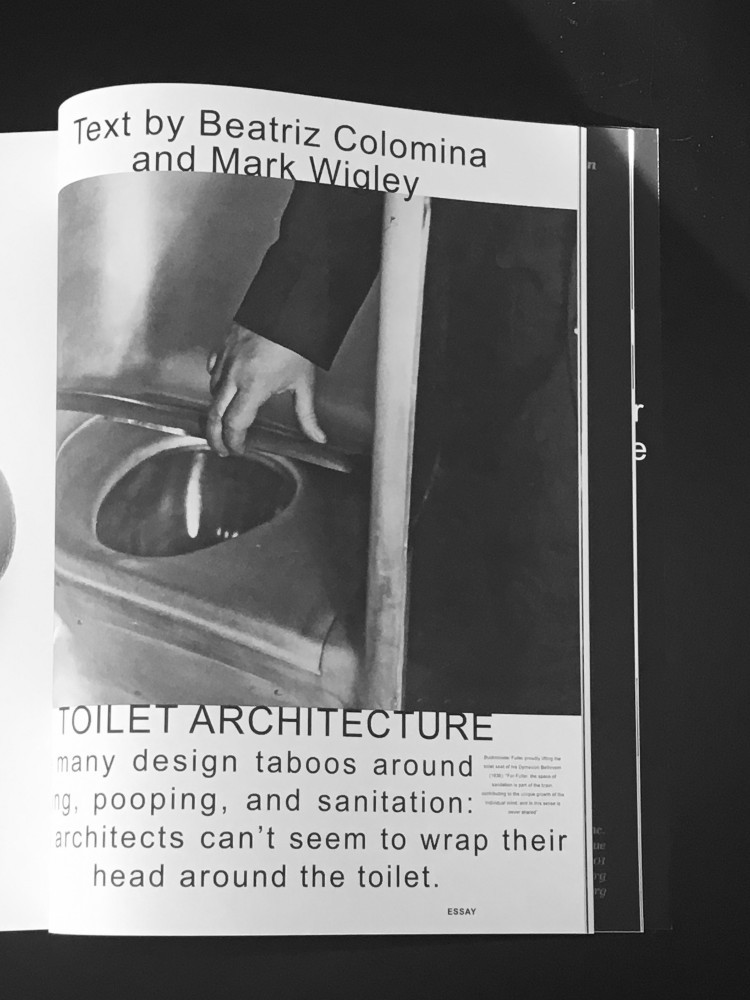

TOILET ARCHITECTURE: AN ESSAY ABOUT THE MOST PSYCHOSEXUALLY CHARGED ROOM IN A BUILDING

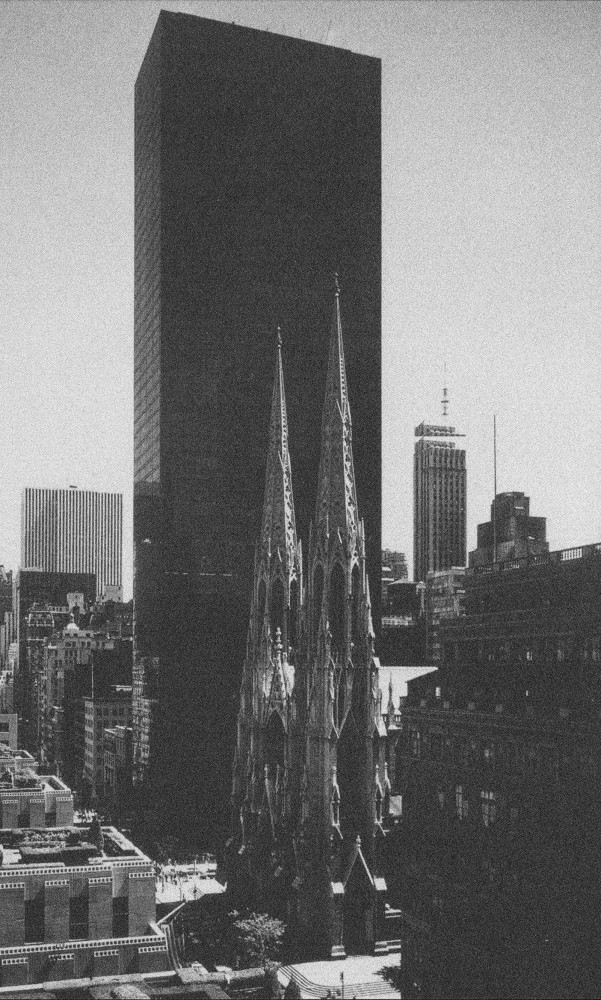

The toilet is the most psychosexually charged room in any building. But to speak of it as a room is already to speak too quickly. The toilet is technology. More precisely, it is a pipe that has been shaped into a piece of furniture so it can be occupied. It is the space where the hidden interior of the body comes into intimate contact with the hidden interior of the building, two plumbing systems temporarily connected. So intense are the psychosexual associations that one of the hallmarks of Anglo-Saxon repression is the mandatory look on emerging from the toilet to show that nothing happened. No one wants to acknowledge the transaction or especially the fact that each toilet is directly connected to the toilets in the neighboring buildings, and on and on in a vast unspeakable empire. To enter the toilet is not to enter the smallest room in a building but to enter a space as big as a city whose smells, noises, flows, and chemical processes are deeply threatening. Toilet technology is designed to whisk away all visual, acoustic, and olfactory evidence of both the interior of the body and the vast interior of this abject urbanism — such that what is happening can quickly be disavowed, even while it is happening. This ability to keep the smells and noises of the toilet at bay is linked to a wider disavowal of sweat, spit, phlegm, pus, vomit, semen, menstrual blood, and vaginal juices. To talk about architecture without talking about toilets is to operate in denial of whole array of sexual, psychological, and moral economies. For all the endless apparent talk about the body in architecture, architects don’t really want to talk about it. Architectural discourse is a deodorizer.

A history could be written of this deodorizing effect. Postmodern architecture, for example, was toilet free. There was no Postmodern toilet, no desire to return to Greek plumbing while celebrating Classical pediments. Nor is there a Critical Regionalist or Parametric toilet. Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown didn’t offer a complex and contradictory toilet experience. Even the High-tech architects who see all architecture as a form of glorified plumbing largely stay away from the toilet. Zaha Hadid’s posthumously released porcelain “sanitary fittings” took her signature curves into the bathroom, blending toilet and bidet into the walls, but left the basic architecture of the toilet intact. It is as if the toilet is simply not open to architectural experiment or speculation. For all the promiscuous inventive talk of architects in which nothing seems off limits, the toilet is treated as a kind of given — something to be simply selected from a catalogue. Its look might need to be harmonized with the interior, and it can be a marvel of innovation — as in the extraordinarily complex apparatus of Japanese toilets requiring a driver’s license in which sprays, rinses, temperature, and vibrations can be electronically controlled and chemical analysis is carried out in real time with forensic precision — but the toilet itself is outside the architect’s purview. Architects are not known for their toilet philosophy and design students are rarely asked to explain what kind of space they prescribe for shitting and peeing. The door to the toilet remains discreetly closed.

But this sanitized discourse is itself a historical effect. Modern architects spent a lot of time in the toilet — not simply searching for modern plumbing but seeing the toilet as crucial a way of modernizing architecture. For them, the question was not so much what it meant to enter the toilet as what it meant for the toilet to enter architecture. In that sense, the history of Modern architecture could be written from the point of view of the toilet. Modern architects turned private bathrooms into public spaces and in so doing sexualized architecture. From Adolf Loos and his poetry on American plumbing to Le Corbusier, who used the bidet as a polemical device by placing it in the middle of the living space of the house, to Paul Rudolph and his Manhattan penthouse whose entrance lobby provides a view up through the bottom of the glass bathtub above, Modern architecture challenged traditional morality.

Loos’s writings are full of scatological references. In his magazine Das Andere (subtitled A Journal for the Introduction of Western Culture into Austria, published in just two issues in 1903), he compares Austria to America in terms of the use of toilet paper (absent in the former and ubiquitous in the latter). The critic and journalist Karl Kraus, his great friend and ally in the campaign against the decorative impulses of the Austrian Secessionist movement, ridiculed their contributions to culture using the chamber pot as a reference point:

“All that Adolf Loos and I have done, he literally and I verbally, is to show that there is a difference between an urn and a chamber pot, and that in that difference there is latitude for culture.” (Die Fackel, December 15, 1913.)

In his essay The Plumbers (1898), Loos wrote that “the only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges,” anticipating by almost two decades Marcel Duchamp, who, in response to the rejection of his porcelain urinal Fountain by the Society of Independent Artists for being “plagiarism, a plain piece of plumbing,” reputedly said, “The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges” (a phrase used by Beatrice Wood in her defense of the piece in the magazine The Blind Man).

Frank Lloyd Wright, who said he arrived in architecture at the same time as modern plumbing, was extremely proud to have invented the idea of toilet bowls suspended off the wall for ease of cleaning, along with the partitions between them, in the Larkin Company administration building (Buffalo, New York, 1906). Indeed he was so proud that he published the toilet bowl in question — invented, what’s more, for a company whose products included Oatmeal toilet soap — in the April 1908 issue of The House Beautiful. He was always sensitive to the proximity, cleanliness, and view of toilets, argued that combined modern sanitary units could be delivered to houses like cars, and was convinced that squatting was the most healthful way to defecate. The toilet with large windows overlooking the landscape in his most famous house, Fallingwater (Mill Run, Pennsylvania, 1937), is therefore just 10.5 inches off the floor.

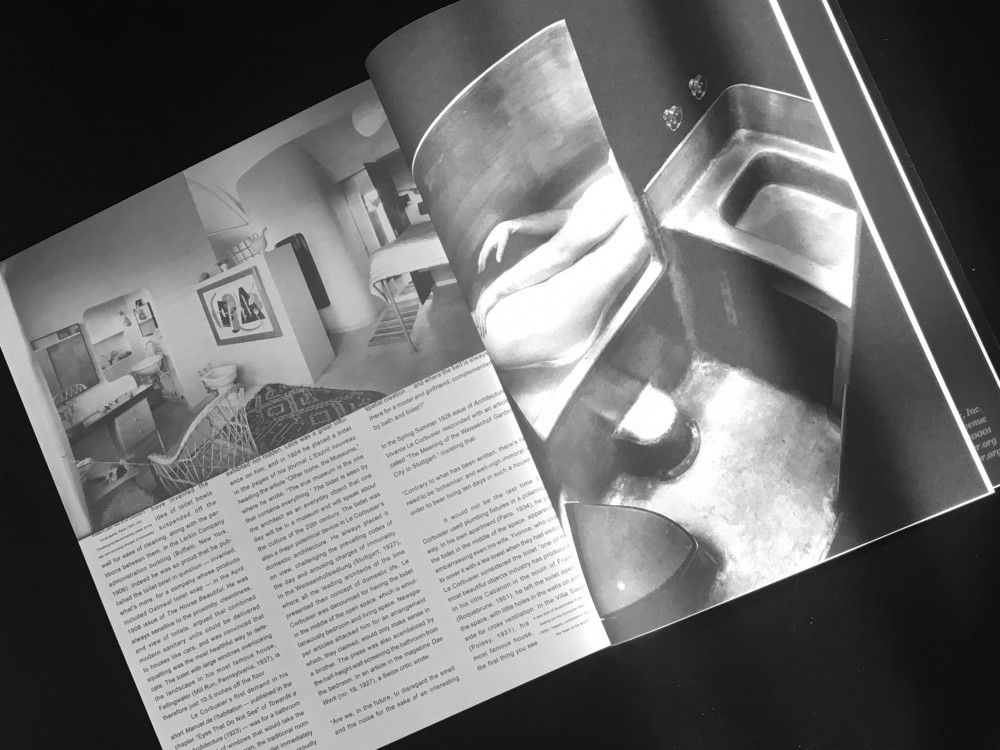

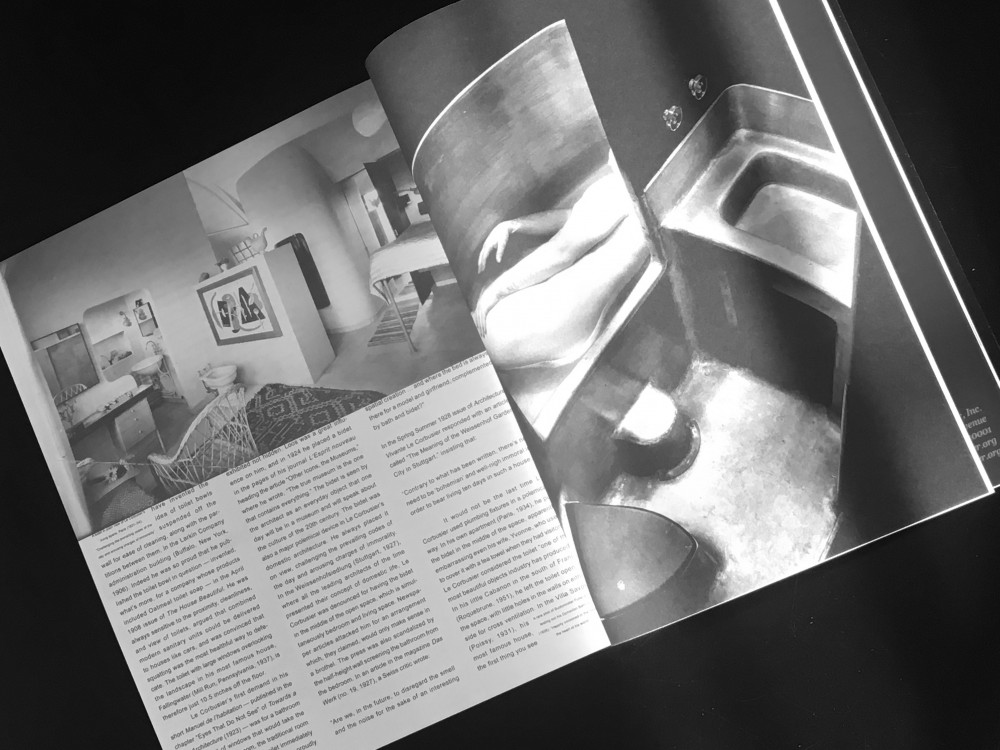

Le Corbusier’s first demand in his short Manuel de l’habitation — published in the chapter "Eyes That Do Not See" of Towards a New Architecture (1923) — was for a bathroom with a wall all of windows that would take the place of the drawing room, the traditional room for meeting visitors, with the toilet immediately adjacent. Sanitary fittings were to be proudly exhibited not hidden. Loos was a great influence on him, and in 1924 he placed a bidet in the pages of his journal L’Esprit nouveau heading the article "Other Icons, the Museums," where he wrote, “The true museum is the one that contains everything.” The bidet is seen by the architect as an everyday object that one day will be in a museum and will speak about the culture of the 20th century. The bidet was also a major polemical device in Le Corbusier’s domestic architecture. He always placed it on view, challenging the prevailing codes of the day and arousing charges of immorality. In the Weissenhofsiedlung (Stuttgart, 1927), where all the leading architects of the time presented their concept of domestic life, Le Corbusier was denounced for having the bidet in the middle of the open space, which is simultaneously bedroom and living space. Newspaper articles attacked him for an arrangement which, they claimed, would only make sense in a brothel. The press was also scandalized by the half-height wall screening the bathroom from the bedroom. In an article in the magazine Das Werk (no. 19, 1927), a Swiss critic wrote:

“Are we, in the future, to disregard the smell and the noise for the sake of an interesting spatial creation … and where the bed is always there for a model and girlfriend, complemented by bath and bidet?”

In the Spring Summer-1928 issue of Architecture Vivante, Le Corbusier responded with an article called "The Meaning of the Weissenhof Garden City in Stuttgart," insisting that:

“Contrary to what has been written, there’s no need to be ‘bohemian’ and well-nigh immoral in order to bear living ten days in such a house.”

It would not be the last time Le Corbusier used plumbing fixtures in a polemical way. In his own apartment (Paris, 1934), he put the bidet in the middle of the space, apparently embarrassing even his wife, Yvonne, who used to cover it with a tea towel when they had visitors. Le Corbusier considered the toilet “one of the most beautiful objects industry has produced.” In his little Cabanon in the south of France (Roquebrune, 1951), he left the toilet open to the space, with little holes in the walls on either side for cross ventilation. In the Villa Savoye (Poissy, 1931), his most famous house, the first thing you see when you enter is a plumbing fixture, a white sink positioned at the beginning of the promenade architecturale like a work of art in a museum. And the most elaborate space in the house is the bathroom, with its sunken bathtub and built-in chaise longue in blue tiles like a sensuous body in the space, or the space itself becoming a sensual body. The bathroom is not really a room; it is open to the rest of the house thereby sexualizing the whole internal landscape.

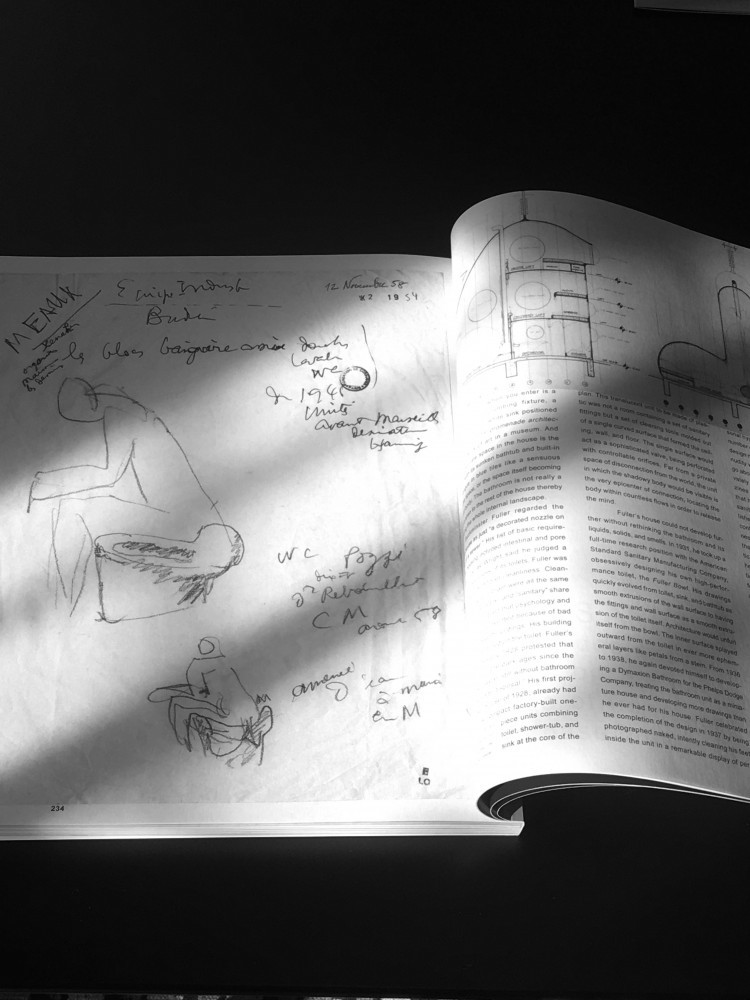

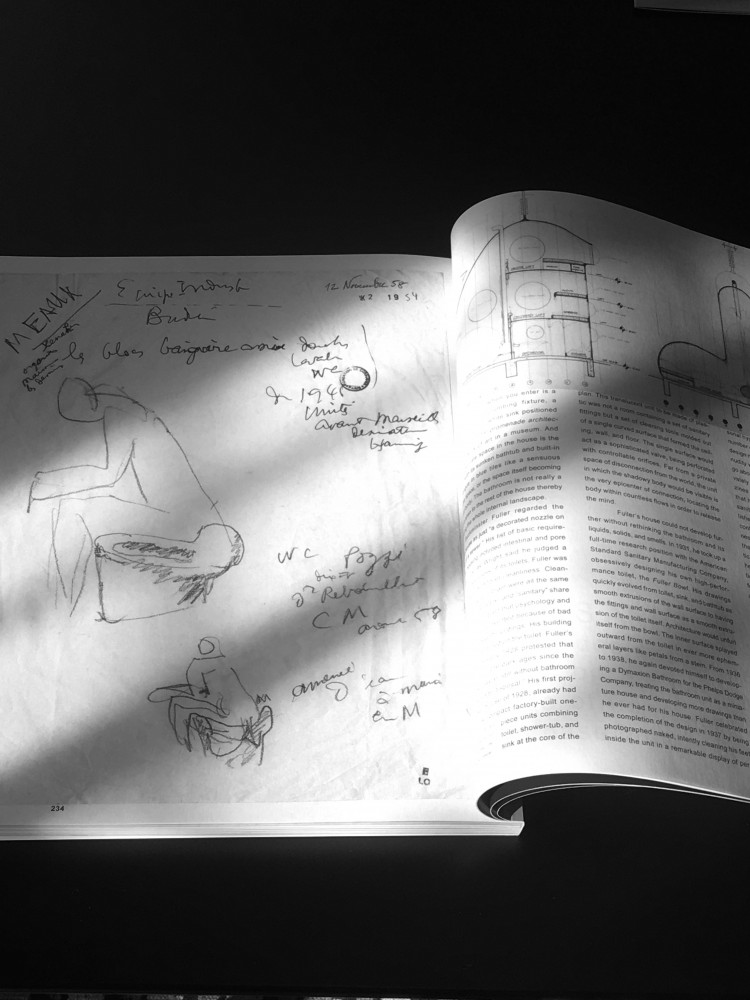

Buckminster Fuller regarded the average house as just “a decorated nozzle on the end of a sewer.” His list of basic requirements for housing included intestinal and pore cleansing. Just as Wright said he judged a hotel by the cleanliness of its toilets, Fuller was hyper-obsessed with toilet cleanliness. Cleaning body, building, and brain were all the same thing. He noted that “sane” and “sanitary” share the same root and argued that psychology and psychiatry were only invented because of bad plumbing in bodies and buildings. His building designs were all centered on the toilet. Fuller’s first manuscript in early 1928 protested that society remained in the dark ages since the majority of houses were “still without bathroom or toilets and sewage disposal.” His first project, the 4D Tower House of 1928, already had two back-to-back compact factory-built one-piece units combining toilet, shower-tub, and sink at the core of the plan. This translucent unit to be made of plastic was not a room containing a set of sanitary fittings but a set of cleaning tools molded out of a single curved surface that formed the ceiling, wall, and floor. The single surface would act as a sophisticated valve, being perforated with controllable orifices. Far from a private space of disconnection from the world, the unit in which the shadowy body would be visible is the very epicenter of connection, locating the body within countless flows in order to release the mind.

Fuller’s house could not develop further without rethinking the bathroom and its liquids, solids, and smells. In 1931 he took up a full-time research position with the American Standard Sanitary Manufacturing Company, obsessively designing his own high-performance toilet, the “Fuller Bowl.” His drawings quickly evolved from toilet, sink, and bathtub as smooth extrusions of the wall surface to having the fittings and wall surface as a smooth extrusion of the toilet itself. Architecture would unfurl itself from the bowl. The inner surface splayed outward from the toilet in ever more ephemeral layers like petals from a stem. From 1936 to 1938 he again devoted himself to developing a “Dymaxion Bathroom” for the Phelps Dodge Company, treating the bathroom unit as a miniature house and developing more drawings than he ever had for his house. Fuller celebrated the completion of the design in 1937 by being photographed naked, intently cleaning his feet inside the unit in a remarkable display of personal hygiene published without comment in a number of architecture, literature, and interior-design magazines in the USA and England. The nudity went unnoticed — as if he were able to go about his personal rituals of hygiene as privately on the pages of mass-circulation magazines as within the house itself, or any house that had been enhanced by this new piece of sanitary equipment. In a remarkable unpublished image from the same photo shoot, Fuller confidently presents his naked rear end to us, nestled within the curves of the metal bathroom that was designed to be of translucent plastic. He is happily cocooned in the heart of the heart of his world, in which frequent evacuation, cleanliness, sensuality, architectural performance, and the performance of the architect are one — a polemically personal manifesto to the infinite hospitality of the toilet renders his colleagues forever modest.

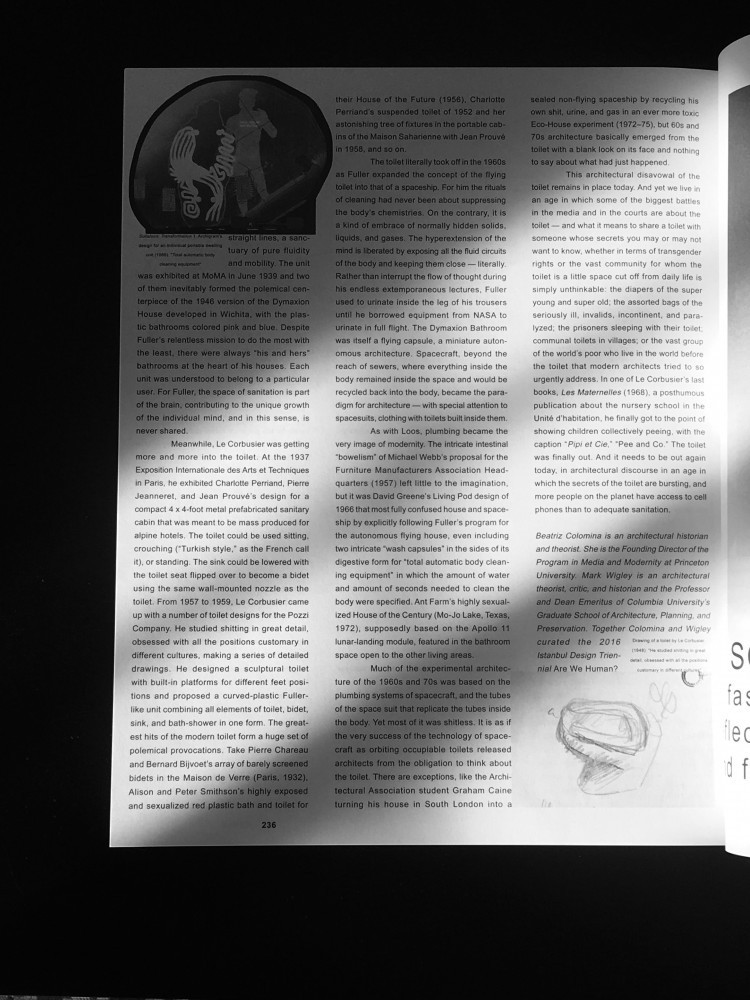

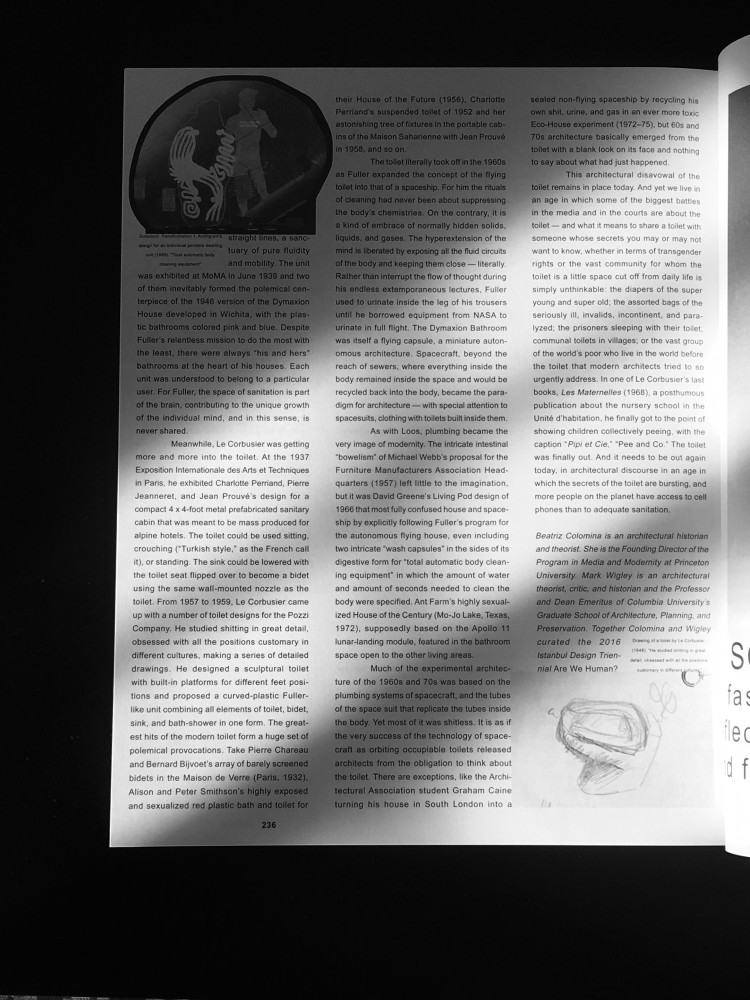

Nothing coming out of the body would leave the house. Even solid waste was automatically shrink-wrapped for later use. Fuller imagined that people would want to take their bathroom with them, as a kind of prized possession or even as an intimate extension or container of their body. The toilet space would be at once the most intimate space and the most mobile. It was like a portable personal cave with its internal curves closely molded to the curves of the body and internally heated to the same temperature. It was in every sense a frictionless space with a single naked person smoothly nestled inside it. A uterine haven from straight lines, a sanctuary of pure fluidity and mobility. The unit was exhibited at MoMA in June 1939 and two of them inevitably formed the polemical centerpiece of the 1946 version of the Dymaxion House developed in Wichita, with the plastic bathrooms colored pink and blue. Despite Fuller’s relentless mission to do the most with the least, there were always “his and hers” bathrooms at the heart of his houses. Each unit was understood to belong to a particular user. For Fuller, the space of sanitation is part of the brain, contributing to the unique growth of the individual mind, and in this sense is never shared.

Meanwhile, Le Corbusier was getting more and more into the toilet. At the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques in Paris, he exhibited Charlotte Perriand, Pierre Jeanneret, and Jean Prouvé’s design for a compact 4 x 4-foot metal prefabricated sanitary cabin that was meant to be mass produced for alpine hotels. The toilet could be used sitting, crouching (“Turkish style,” as the French call it), or standing. The sink could be lowered with the toilet seat flipped over to become a bidet using the same wall-mounted nozzle as the toilet. From 1957 to 1959, Le Corbusier came up with a number of toilet designs for the Pozzi Company. He studied shitting in great detail, obsessed with all the positions customary in different cultures, making a series of detailed drawings. He designed a sculptural toilet with built-in platforms for different feet positions and proposed a curved-plastic Fuller-like unit combining all elements of toilet, bidet, sink, and bath-shower in one form. The greatest hits of the modern toilet form a huge set of polemical provocations. Take Pierre Chareau and Bernard Bijvoet’s array of barely screened bidets in the Maison de Verre (Paris, 1932), Alison and Peter Smithson’s highly exposed and sexualized red plastic bath and toilet for their House of the Future (1956), Charlotte Perriand’s suspended toilet of 1952 and her astonishing tree of fixtures in the portable cabins of the Maison Saharienne with Jean Prouvé in 1958, and so on.

The toilet literally took off in the 1960s as Fuller expanded the concept of the flying toilet into that of a spaceship. For him the rituals of cleaning had never been about suppressing the body’s chemistries. On the contrary, it is a kind of embrace of normally hidden solids, liquids, and gases. The hyperextension of the mind is liberated by exposing all the fluid circuits of the body and keeping them close — literally. Rather than interrupt the flow of thought during his endless extemporaneous lectures, Fuller used to urinate inside the leg of his trousers until he borrowed equipment from NASA to urinate in full flight. The Dymaxion Bathroom was itself a flying capsule, a miniature autonomous architecture. Spacecraft, beyond the reach of sewers, where everything inside the body remained inside the space and would be recycled back into the body, became the paradigm for architecture — with special attention to spacesuits, clothing with toilets built inside them.

As with Loos, plumbing became the very image of modernity. The intricate intestinal “bowelism” of Michael Webb’s proposal for the Furniture Manufacturers Association Headquarters (1957) left little to the imagination, but it was David Greene’s Living Pod design of 1966 that most fully confused house and spaceship by explicitly following Fuller’s program for the autonomous flying house, even including two intricate “wash capsules” in the sides of its digestive form for “total automatic body cleaning equipment” in which the amount of water and amount of seconds needed to clean the body were specified. Ant Farm’s highly sexualized House of the Century (Mo-Jo Lake, Texas, 1972), supposedly based on the Apollo 11 lunar-landing module, featured a dramatic exposed toilet fed by a thick transparent tube descending from a visible chamber in a free-standing blob in the bathroom space open to the other living areas.

Much of the experimental architecture of the 1960s and 70s was based on the plumbing systems of spacecraft, and the tubes of the space suit that replicate the tubes inside the body. Yet most of it was shitless. It is as if the very success of the technology of spacecraft as orbiting occupiable toilets released architects from the obligation to think about the toilet. There are exceptions, like the Architectural Association student Graham Caine turning his house in South London into a sealed non-flying space ship by recycling his own shit, urine, and gas in an ever more toxic “Eco-House” experiment (1972–75), but 60s and 70s architecture basically emerged from the toilet with a blank look on its face and nothing to say about what had just happened.

This architectural disavowal of the toilet remains in place today. And yet we live in an age in which some of the biggest battles in the media and in the courts are about the toilet — and what it means to share a toilet with someone whose secrets you may or may not want to know, whether in terms of transgender rights or the vast community for whom the toilet as a little space cut off from daily life is simply unthinkable: the diapers of the super young and super old; the assorted bags of the seriously ill, invalids, incontinent, and paralyzed; the prisoners sleeping with their toilet; communal toilets in villages; or the vast group of the world’s poor who live in the world before the toilet that modern architects tried to so urgently address. In one of Le Corbusier’s last books, Les Maternelles (1968), a posthumous publication about the nursery school in the Unité d’habitation, he finally got to the point of showing children collectively peeing, with the caption “Pipi et Cie,” “Pee and Co.” The toilet was finally out. And it needs to be out again today, in architectural discourse in an age in which the secrets of the toilet are bursting, and more people on the planet have access to cell phones than to adequate sanitation.

Text by Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley.

Taken from PIN–UP No. 23, Fall Winter 2017/18.