INTERVIEW: Nargis and Nasir Kassamali’s Faith in Design as a Language

Few retailers have done more to promote contemporary design in the US than Nargis and Nasir Kassamali, the Kenyan-born entrepreneurs and founders of the design emporium Luminaire. The septuagenarian power couple is based in Miami, where Luminaire was founded back in 1974, but Luminaire the company has since successfully proliferated, with outposts in Chicago, Los Angeles, and more to come (in 2017 American design giant Haworth became Luminaire’s majority partner). What distinguishes Luminaire in the marketplace is the Kassamalis’ unflinching passion for educating, create sustainable networks, and democratize design knowledge by making it available to anyone whose minds are curious enough to explore and learn. The goal, to use one of Kassamali’s favorite analogies, is to make people experience design “like a third skin,” and understanding it as a universal language. Such dedication to the cause hasn’t gone unnoticed by the design industry, which found in the couple impassioned ambassadors for quality, originality, and authenticity — most important in a field where copying is often still considered a cavalier offense, this lead to the Kassamali’s being awarded the design industry’s highest honors for a lifetime of celebrating design: the 2020 Compasso d'Oro. Far from looking towards retirement, the Kassamali’s are facing a new surge in customers driven by a pandemic-induced urge to rediscover design, keeping Luminaire’s over 80 employees busier than ever. Nasir Kassamali, one half of the founding couple, found time to talk to PIN–UP from their home in Miami, to reminisce about humble beginnings, his and wife's lifetime mission, and the most valuable element in your home (hint: it’s not an object).

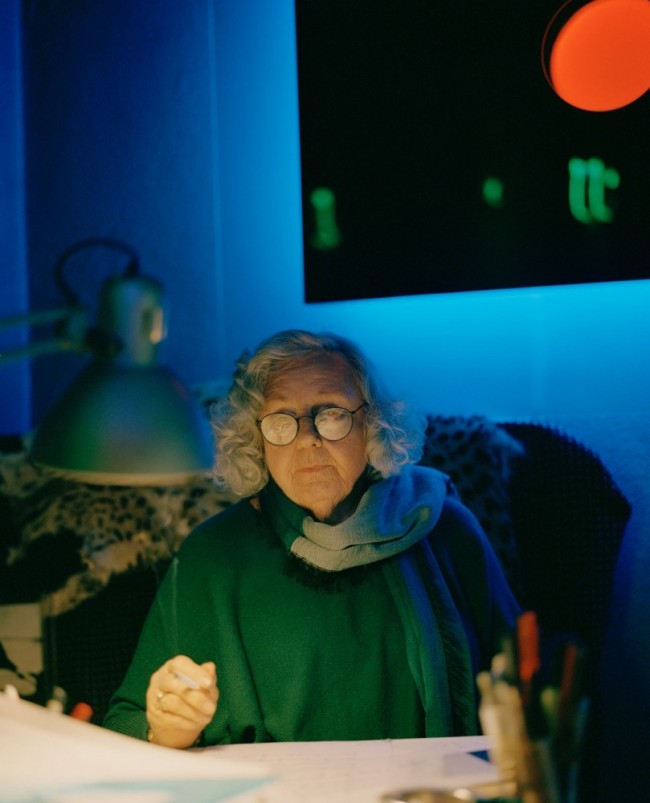

Nasir and Nargis Kassamali on the signature black steel-clad central staircase in the Luminaire Coral Gables showroom. Photographed by Devin Christopher for PIN–UP.

Felix Burrichter: When you were growing up in Kenya in the 1950s, could you have imagined that 70 years later, you would be based in Miami, at the head of an international design empire?

Nasir Kassamali: No. But I always knew I was different. I was always a very curious kid. For example, I was a vegetarian even when the rest of the family all ate meat and fish. They sometimes even joked that I got mixed up in the hospital. (Laughs.) My father and grandfather had a business of generating power in Mombasa, and they were outfitting all the big offices and government buildings with lighting. Travel was very restricted, but they were allowed to go to the UK to make purchases, and from there, my father would go to Germany to buy industrial lighting. He’d also always bring back design and architecture magazines for me, and so from a very young age, I knew the work of Gio Ponti, and so on. One time my father brought back a book about the Bauhaus, because one of the workers in the factory in Germany had recommended he get one for me. I still have the book to this day. It was incredible because it completely altered my way of thinking. I even started applying ideas from the book to my parents’ house. Pretty soon, the house was very contemporary, devoid of any classic English furniture — very minimal. So I started to formulate ideas about design thinking from a very young age.

It sounds like everything pointed to you becoming an architect.

Yes. But my father and grandfather were both electrical engineers, and so they also wanted me to become an electrical engineer instead. But my teachers at the university in Nairobi were from Denmark and Norway, and they would tell me: “What are you doing in electrical engineering? Your vocabulary, the way you see things — you think like an architect. You should be in architecture school.” But to my benefit, to this day the way I approach a problem is very different than most people, and that's because of my engineering background.

Is it at university that you met your wife, Nargis?

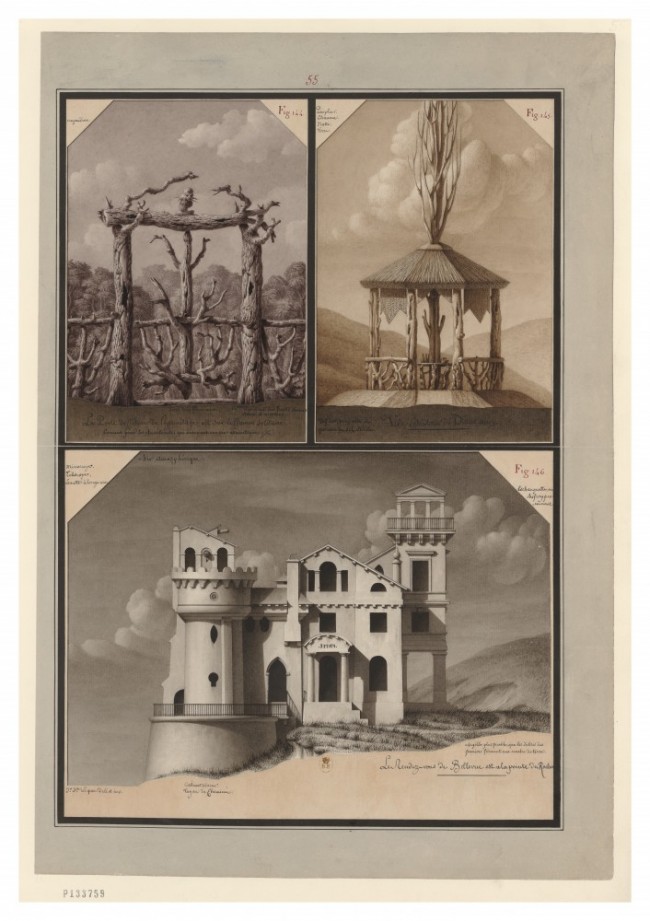

Yes, it was during my final year that I met Nargis. We signed up for an exchange program between my university and a Danish university in Copenhagen, and we both got accepted. This was in 1970. And as soon as we landed we went straight to this location called Den Permanente, where for the first time we could see in person the work of Alvar Aalto, Hans Wegner, Le Corbusier... it was unbelievable! That summer they also had an exhibition of the Bauhaus in a separate room. That's where Nargis and I understood that our future would not be in Kenya, but somewhere where we could create a church for design, where people could experience and appreciate it.

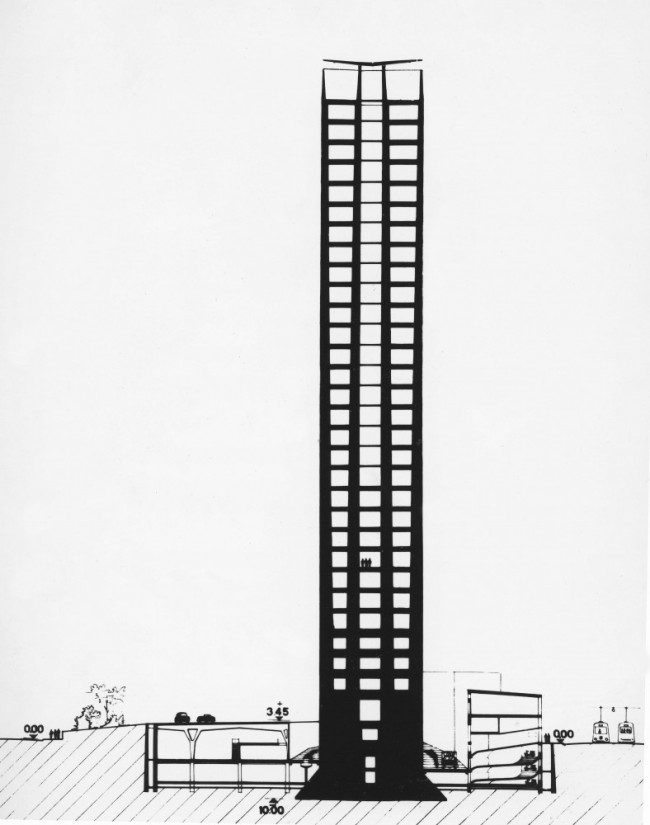

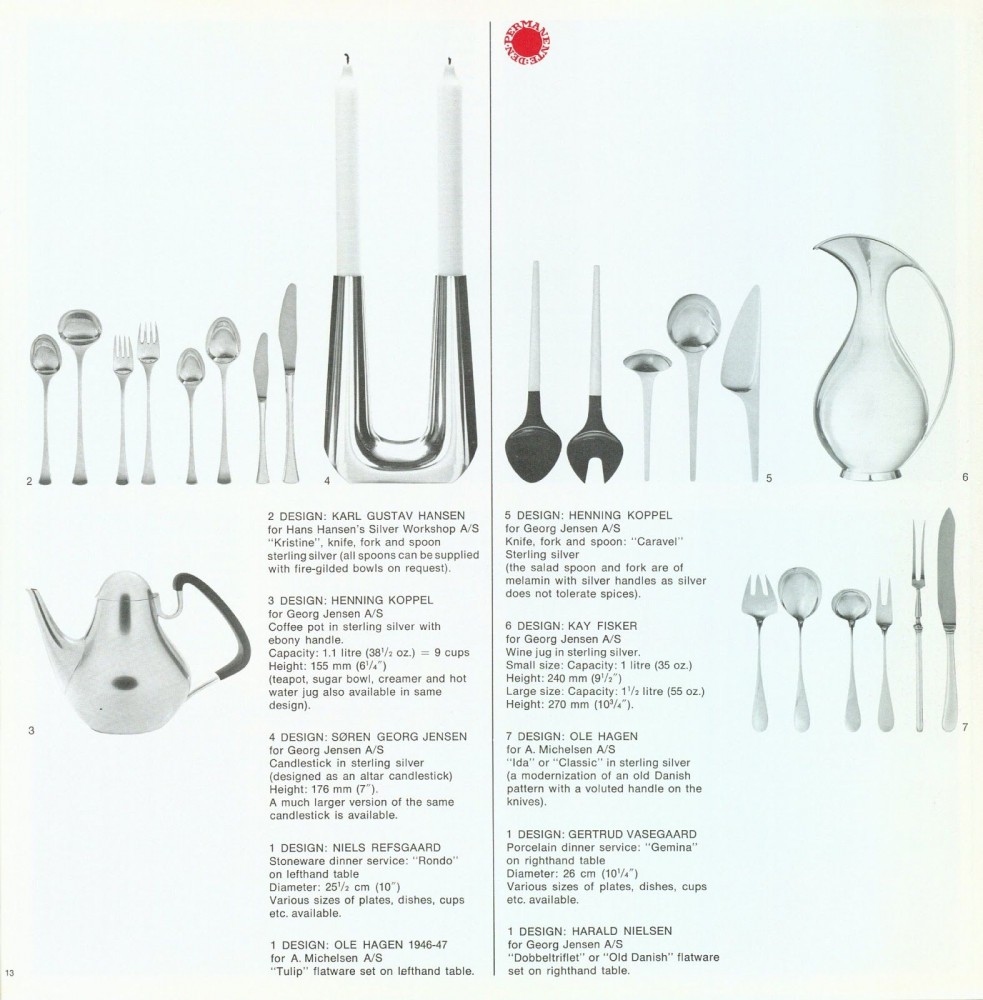

Exterior view of Den Permanente in Copenhagen (c. 1970), a permanent exhibition space and store for Danish applied arts that operated between 1931–81. Nasir and Nargis Kassamali visited in 1970.

Do you think in the 50 years since you’ve been trying to recreate that first experience that you had that day in Copenhagen?

Every day! The idea to create a design driven company started during that trip. Nargis and I spent three more months traveling together to London, Paris, Milan and Barcelona. We didn’t have a lot of money because Kenyan currency wasn’t recognized internationally, so we often stayed at youth hostels. But when we were in Milan I already started doing studio visits with designers. I had the address for Marco Zanuso’s studio and we were able to see some of the early prototypes they were working on. Nargis understood more and more what my dream was and the more she understood what made me happy inside, the more I fell in love with her. Even if that meant we had to sleep on a railway bench, she was game for it. (Laughs.) I knew I had found my soulmate.

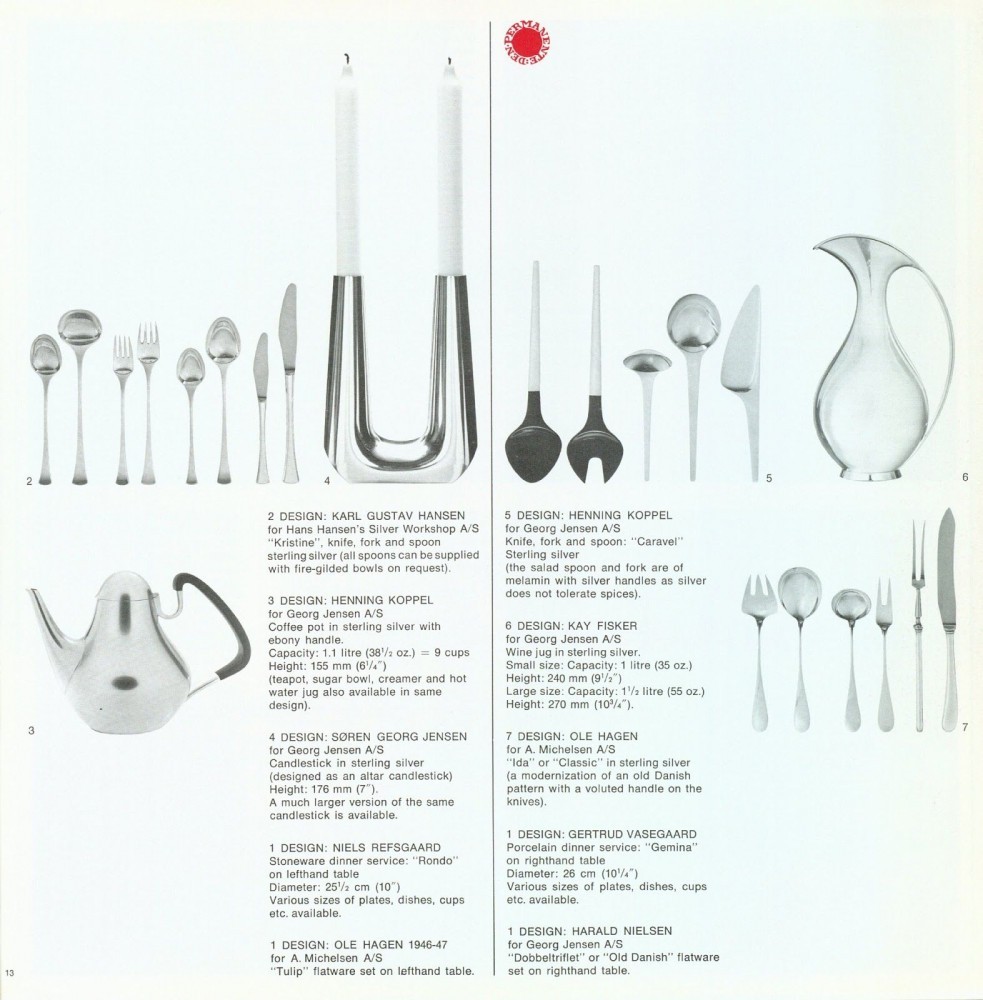

1972 Catalogue of Den Permanente in Copenhagen, featuring Scandinavian design classics.

How did Nargis and you plan your future?

Our plan was to marry once Nargis finished university in Nairobi. In the meantime, I worked as a designer in Mombasa, designing hotels and shops and so forth, all with local materials and with the few things that our company could order or was allowed to order. Once Nargis graduated we got married in London. It was a difficult time because that year Idi Amin in Uganda threw out all the Indians, and we were afraid something similar was going to happen in Kenya. Since we were recently married and had no children, our parents recommended we settle down somewhere else. From London we went to Montreal in Canada, because Kenya and Canada were both former British colonies.

Going from Mombasa to Montreal must have been quite a culture shock.

Yes. And there was 40 centimeters of snow; it was horrible. From there we went to Toronto, but we didn’t like it either. But in Toronto I ran into a friend whose house I'd designed in Mombasa, and he said, “What are you guys doing here? You should come to Miami, it's nice and warm there.” We followed his advice and I remember we arrived in Miami in the middle of November and it was beautiful temperature, palm trees — it felt exactly like Mombasa. We knew we were going to stay.

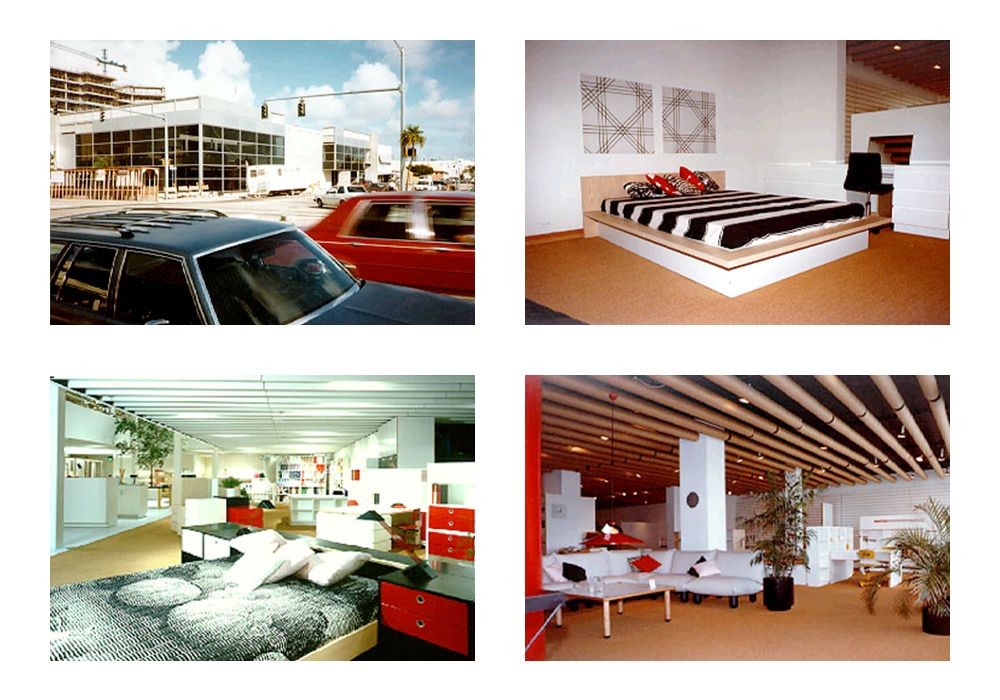

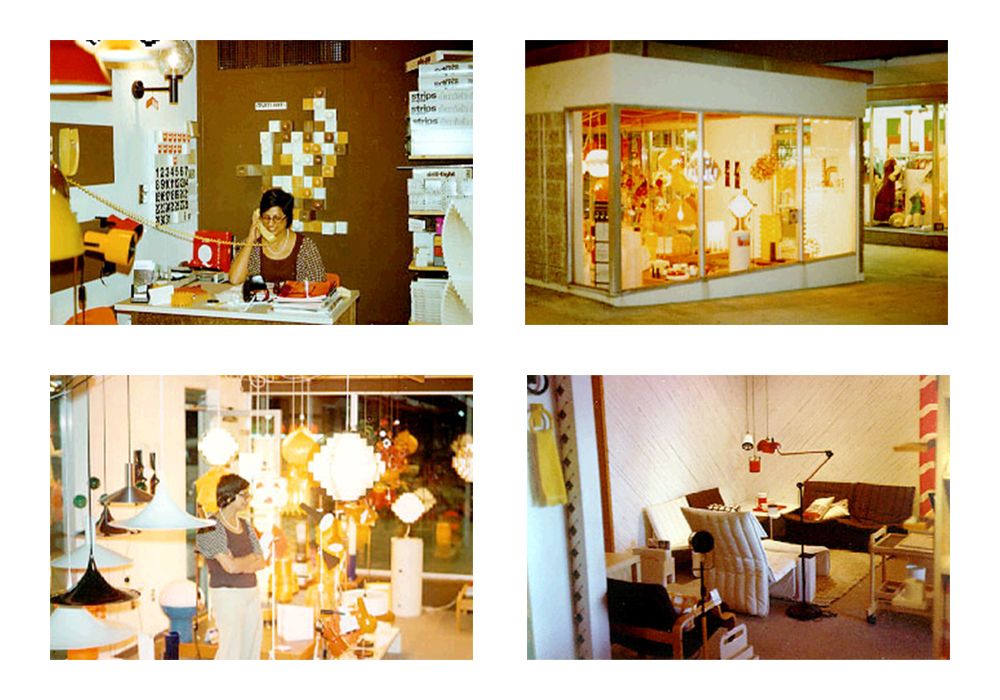

Archival images of Luminaire's first locations, including the lighting kiosk in North Miami Beach, which Nargis and Nasir Kassamali opened in 1974.

How did the idea for Luminaire start?

We went looking all over Miami for furniture for our friend's house that we were designing for him and we couldn't find anything. So our friend suggested that we start our own store. I remember him saying, “Miami needs it. This is your chance to make it happen.” Nargis and I didn't come with tons of money. Together we had about 10,000 dollars. But we found a small space, which was 500 square feet, and we only sold lighting. That’s why we called it Luminaire.

And it was an instant success?

Not really. The first day we did 300 dollars in sales, and then the next five days: nothing. We were so desperate, we would open the store to anyone, at any time of the day. One day this guy walks in and says “What is this thing?” pointing at the Semi lamp by Thorsten Thorup and Clause Bonderup. Once I explained it to him he asked me to teach his students about it — he was an architecture professor at the University of Miami, and he was also an architect. Soon enough he also sent his clients our way, and slowly but surely business took off. Two years later we opened a bigger store. And two years after we opened an even bigger store. The idea was to create a complete space, a space of knowledge, and an experience. That’s why I always refer to design as a third skin.

What do you mean by “design as a third skin”?

The first skin is the skin you're born with. You pinch it and it communicates pain or you stroke it communicates sensuality. The degrees are interpreted by the amount of feeling you have. The second skin is the clothes you wear, the clothes you choose for yourself, or that someone decided for you. The question is: do they represent who you are? And how do you feel in them? And then the third skin is the design around you. So not just object oriented, but as a complete space. That’s why I call it the third skin. The best example is the inside of the car. Good marketing for cars always shows you the interiors, so you can imagine how you feel inside of it. And when you leave the car most people leave the feeling behind. But some people carry this bubble around them even when they no longer sitting in the car — it’s an understanding of the world around you, and the aesthetic circles around you grow, and start to be better defined, and the bubble of your third skin grows and grows.

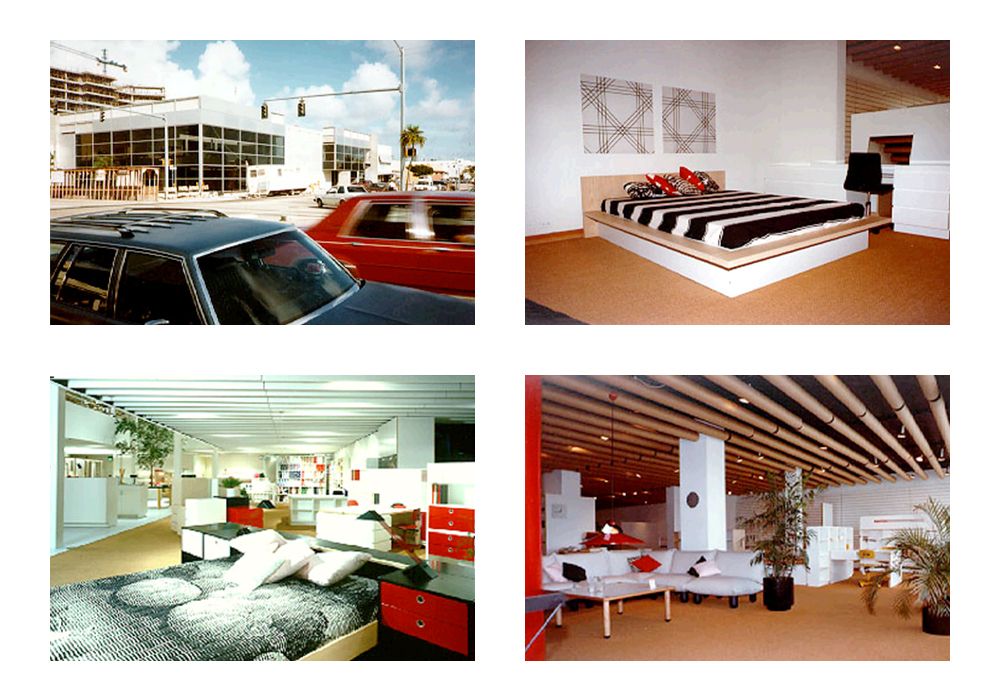

Archive images from Luminaire’s Coral Gables contemporary design showroom from the 1980s, the first of its kind in the U.S.

The fact that you were honored by the Italian design industry with the Compasso D’Oro is also thanks to the many Italian companies you work with. Was that always like that or has that changed over the years?

During the earlier years of Luminaire we worked with a lot more Scandinavian brands and very few Italian brands. But by the time 1980 arrived we had more Italian brands than Scandinavian brands. But to us design is not a national thing. It’s not Italian, or German, or Swedish, or whatever else it may be. Even when you go as far back as the Bauhaus, they were not all German. They were from many different countries and cultural backgrounds. But they shared a philosophy. Some people may look at a Naoto Fukusawa chair for Maruni and they’ll say, “Oh, is this Italian?” Yes, but no, it’s also Japanese. I want to avoid this attachment to nationalities. For me, design is a language on its own. That’s why I’m not into describing a movement, or overly dating things. Design stands on its own, and it is only valid if it has consistency and stands the test of time.

This brings us to the educational mission of Luminaire, which I know is very important to you.

Yes. We never wanted Luminaire to only be a furniture or lighting company. Our whole purpose is to enhance understanding of what design is, that it is not just computer generated or a lot of thought processes going on — it’s also a feeling. And for a long period of time, I fought the mindset that art is not design. I said, art is not design. Art is without compromise and design is with a lot of compromise. But people would not agree with me, but in 1984 I invited Massimo Vignelli to give a lecture in Miami, and that's when he enforced my point: design is a language. It’s not a style. Styles come and go, but design is a language.

-

Luminaire's flagship showroom in Coral Gables, which first opened its doors in 1984.

-

Exterior façade of Luminaire’s Chicago location, which opened in 1989.

-

Luminaire Lab, the Kassamalis’s dynamic Miami Design District location, host to many events and special artist collaborations.

-

Luminaire's Los Angeles showroom on famous Beverly Boulevard. The 15,0000-square foot space is the most recent one to open in the U.S.

Nonetheless you do have to respond to certain trends, no? I recently had a discussion with the architect and researcher Anna Puigjaner about the evolution of the kitchen, for example. It used to be considered the place of labor and efficiency, and now it has become the center of the home, it represents comfort and conviviality. I’m really curious how you have experienced these sorts of trends and evolutions over the past 46 years.

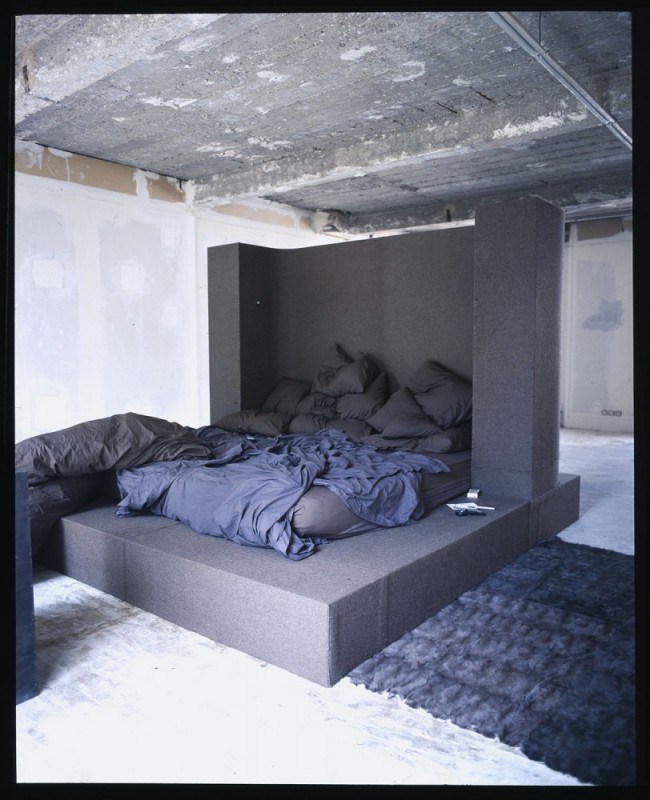

We have an in-house architecture team and when we were working on residential projects back in the 1979 we were the first ones to open the bathrooms. The bathroom is the most sacred place in your home. It’s where you are bare and sometimes by yourself. And they used to be the smallest spaces in most apartments. Every building that I worked on here in Miami, the bathroom has always been so that you can look outside. Even in my own home, our bathroom has a huge skylight and lots of natural light comes in. Ten or 15 years ago I wrote a foreword on what the future bathroom is going to be like and it enforces these ideals. It comes with the sensibility of understanding how precious you are as an individual. The most important element in our home is not the art that you have on the walls or the objects you bought for it — the most valuable thing in your home is you.

I am finding an ideological consistency and dedication to quality at Luminaire, which seems almost counter-intuitive to running a business, which is based on selling new things all the time.

I’m glad you recognize that. I think what we try to do is to deliver not to the appetite but to the emotions of a human being. And over all these years we've learned so many lessons on how to do that, from traveling to exotic places, or from studio visits with designers and architects like Tadao Ando, whom I worship passionately. We bring these experiences with us to Luminaire and our “tribe.” This goes from the arrangement of the coffee cup and the spoon on the tray, to the way the hang tags are organized, the scent in the showrooms — these may seem trivial things, but all of that creates an experience of a sense of wanting to be there. The Luminaire is built with experiences that range from members that have been a part for over 30 years to those who have recently joined, our strength comes from that diverse and rich minds of curious individuals.

Luminaire trucks at the company's warehouse and dispatch center in Coral Gables, Florida.

You almost make Luminaire sound like a religion.

Yes. I actually sometimes tell people that, and I’m only half joking. We have people who communicate the essence of living now in connected mentally, as well as with the soul being connected now, because the amount of joy you get and the peace that you get surrounded by things that evoke meanings to you is significantly better than just a bank account that you have. Especially in this pandemic, people started to understand what they have is one of two things, a box as a shelter for the soul, or a box as a shelter from rain and tears? That's a goal and a mission. I will never allow Luminaire to just be a furniture store.

Interview by Felix Burrichter.

Portraits by Devin Christopher.

All other images courtesy of Luminaire unless otherwise noted.