CONCRETE RESULTS: Arno Brandlhuber Transforms a Former Sicilian Police Station

Forty-five minutes west of Palermo, a three-mile gap prevents the network of roads that outline Sicily’s coastal perimeter from completing itself. The interruption is the legacy of a political struggle which culminated in 1981 with the creation of Sicily’s first nature reserve, the Riserva Naturale Orientata dello Zingaro. The fight was led by a group of three engineers and a lawyer who, in order to prevent the development of this last stretch of virgin coast, had the foresight to buy the land and then refused to budge. They became known locally as the quattro cavalieri dello Zingaro, and it’s thanks to them that the roadway and the likely construction of a nearby oil refinery were scrapped.

Brandlhuber, together with Giacomo Messina, Martha Michalski, and Marco Wagner, stripped all walls of stucco, revealing blocks of creamy volcanic tuff stone typical in Sicilian construction.

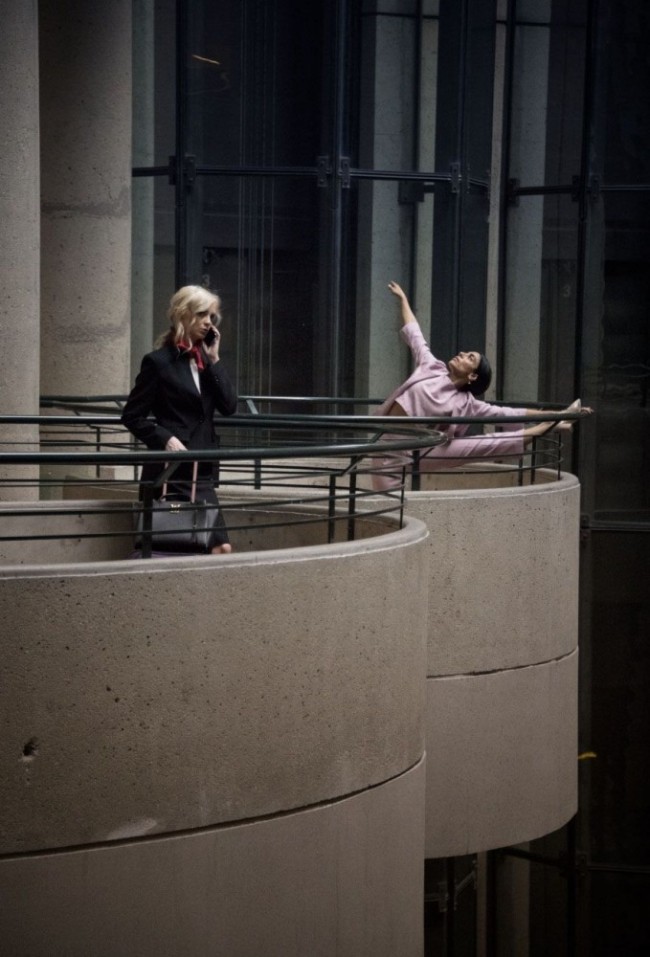

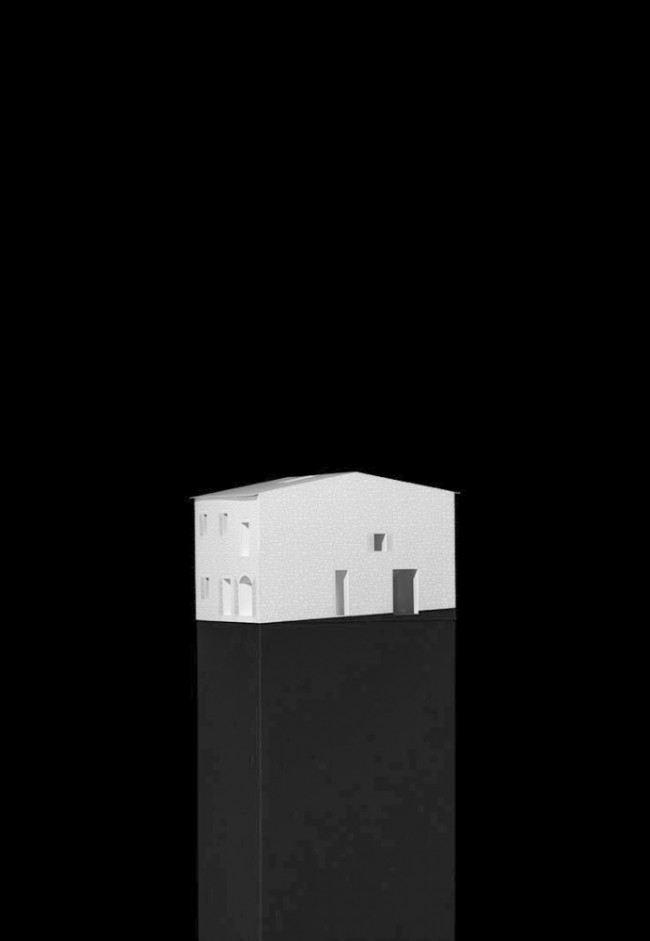

Half a mile or so back down the road, towards the village of Scopello, there is a formerly derelict guesthouse which Berlin-based architect Arno Brandlhuber purchased from the son of one of the cavalieri in 2015. Originally completed in 1976, the building is unremarkable apart from distinctive curving concrete balconies which also feature on the other known buildings by its designer, Michele di Simone. The house first operated as an albergo before being taken over by the Guardia di Finanza, the Italian police force responsible for investigating financial crime and smuggling. After several decades of using the building as their headquarters for customs patrols along the coast, the Guardia abandoned it. Large cracks that had formed sometime in the 1980s due to structural settlement warded off potential buyers, and the house sat empty for several years.

The wooden chevron partitions separate the bathrooms from the rest of the house while baby blue cotton curtains serve as shower curtains and also provide further privacy between living areas. © Erica Overmeer

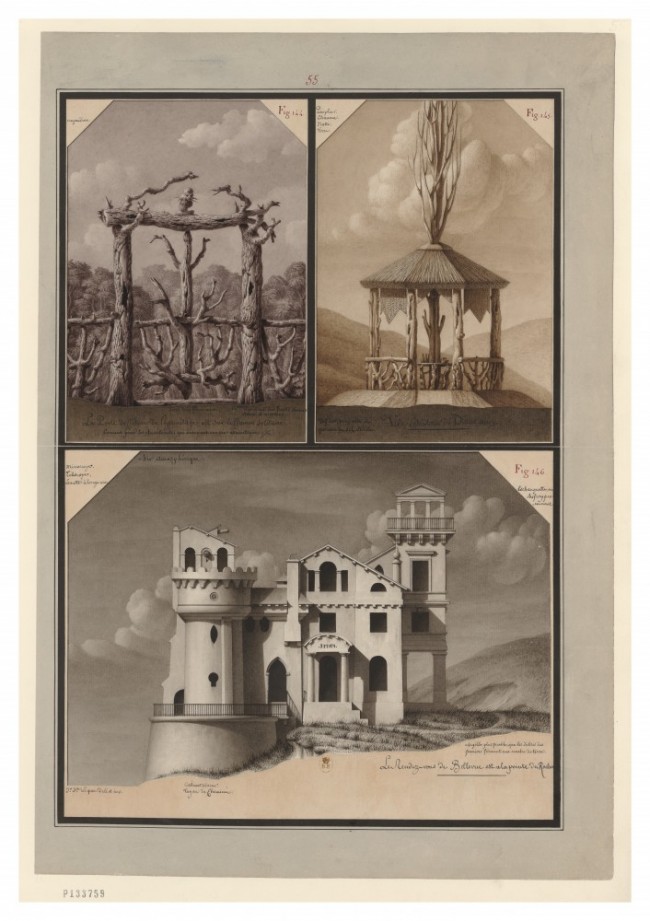

Dubbed simply Finanza, it is the second in a series of collaborative projects that Brandlhuber has undertaken in Sicily in the wake of a two-week travel he made in 2014 to retrace Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s 1804 Italian tour. The trip resulted in the purchase of a house in Castellemmare del Golfo and in the full-time relocation of two members from Brandlhuber’s Berlin office. Working together with Giacomo Messina, Martha Michalski, and Marco Wagner, Brandlhuber and his team took an archaeological approach to the project, peeling back layers of rendering and plaster both inside and out and removing all the interior walls to reveal the building’s structural essence: a concrete frame, typical of 20th-century construction in the area, filled with blocks of creamy tuff stone, a soft volcanic rock used for building in Sicily since Roman times. The two most notable additions to the house are the large sliding windows which completely open up the seaward façade, and a stairway leading up to the rooftop, converting it into a large terrace with panoramic views of the nearby mountains and the Gulf of Castellammare. Regulations in Sicily preclude major alterations within 300 meters of the coastline, however, the team discovered that the local authorities had lost one of the original drawings and found an engineer willing to sign off on the changes.

-

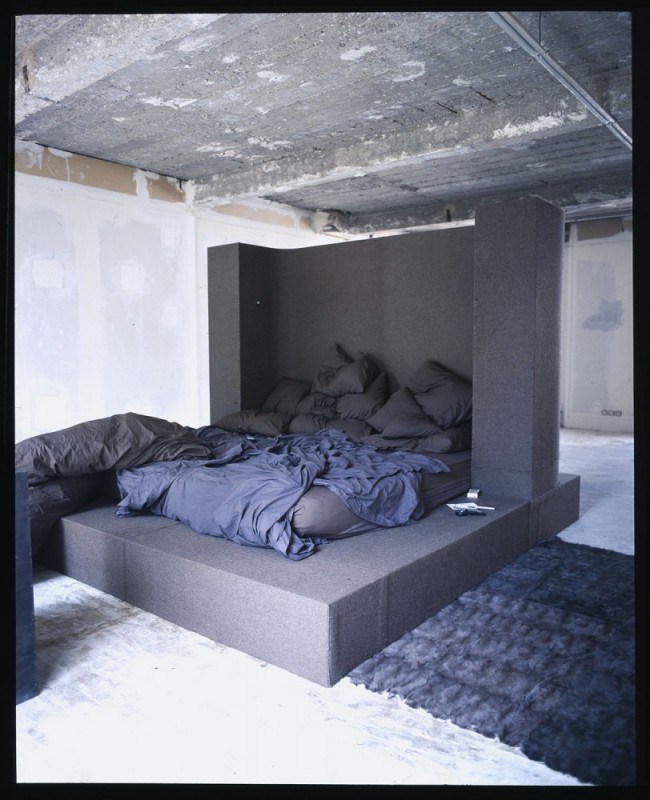

After removing all floor coverings and non-structural walls, Brandlhuber poured new concrete floors and a new staircase.

-

The roof terrace, which is accessed through an industrial steel hatch, offers views over the Mediterranean sea and nearby mountains.

Inside, the floor plan repeats on both levels: a mixture of chevron partitions made from scaffolding planks and ceiling-hung curtains define a large bedroom, a small bedroom, a large bathroom, and a living space. Both bathrooms feature a shower head at the center of the room, encircled by baby blue cotton curtains, turning the daily business of cleansing into a ritual act. The raw finish emphasizes the house’s select provisions: a polished concrete floor, sliding doors made out of single floor-to-ceiling Carrara-marble slabs, and furniture left over from past photo shoots (including two LC5 sofas by Le Corbusier and identical fiberglass beds by Andreas Christen in all four sleeping spaces).

-

The industrial-size sliding windows completely open up the seaward façade and the outdoor patio. Right next to it a set of concrete stairs leads through a bamboo forest to a small, private bay with direct access to the Mediterranean.

-

Located near Scopello, a small fishing village not far from Sicily’s capital Palermo, the building was originally completed in 1976 and was used by the Italian police force as the local headquarters for customs patrols along the coast.

Like his Antivilla in Potsdam (2010–15) — a GDR underwear factory turned weekend home with windows that were crudely enlarged with a sledgehammer — and the concrete retreat he built in Rocha, Uruguay (2011–15), Brandlhuber’s Finanza appears brutally straightforward but is nuanced in its orchestration. Its appeal lies in the opportunities it uncovers. “Normally architecture is about the object. You never discuss it as something time-based, evolving,” says Brandlhuber. “I like old buildings because they already exist and become more like a novel — you’re writing a new chapter.”

Text by Stephen Froese

Photography by Erica Overmeer

Originally published in PIN–UP 25, Fall Winter 2018/19.