CHRISTO AND JEANNE-CLAUDE: A Posthumous Paris Rendezvous at the Pompidou

On May 31 this year, the artist known as Christo quit this mortal coil at the age of 84 — eleven years after his wife and partner in crime Jeanne-Claude. They were both born on June 13, 1935. Had the pandemic not shut down the whole of France, he would still have been alive for the planned inauguration of the exhibition Christo et Jeanne-Claude, Paris! at the Centre Georges-Pompidou, which was scheduled for March 18. Perhaps he might have even lived to see the realization of a 60-year-old dream in L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped, initially scheduled for September 19 and now postponed by a year to September 18, 2021 (the cause of his death has not been given). As it was, the Paris exhibition, orphaned from the event that should have been its culmination, opened posthumously at the beginning of July; what was intended as a celebration of the living has become an exercise in nostalgia. But for those in need of a tonic in these troubling times, this little show is a godsend.

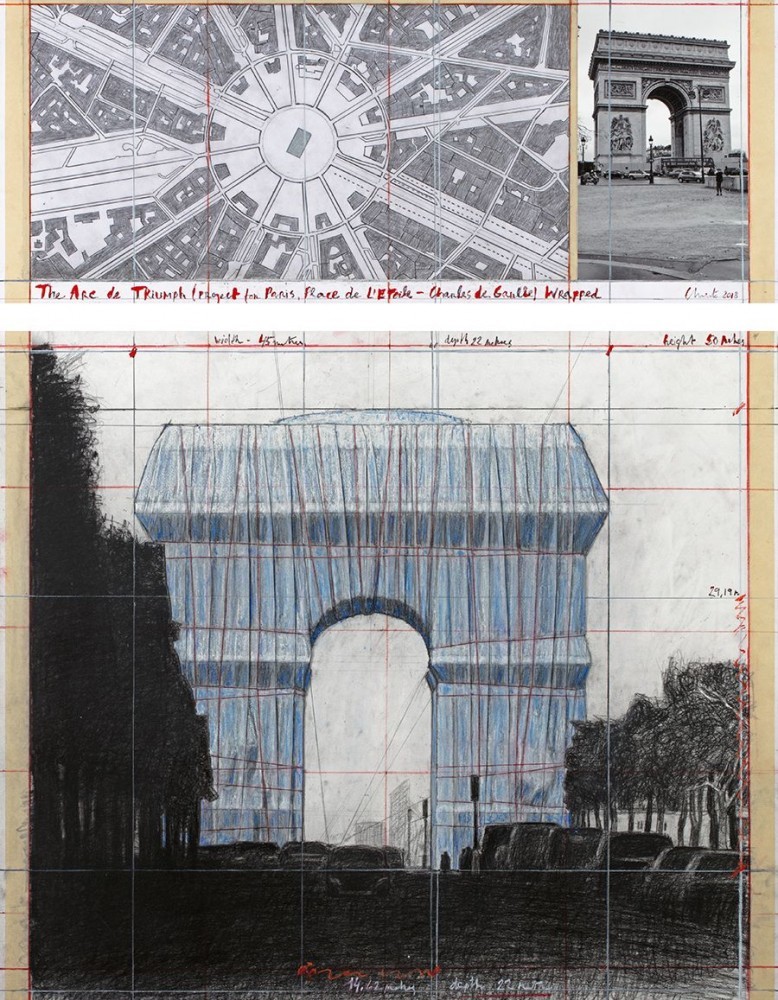

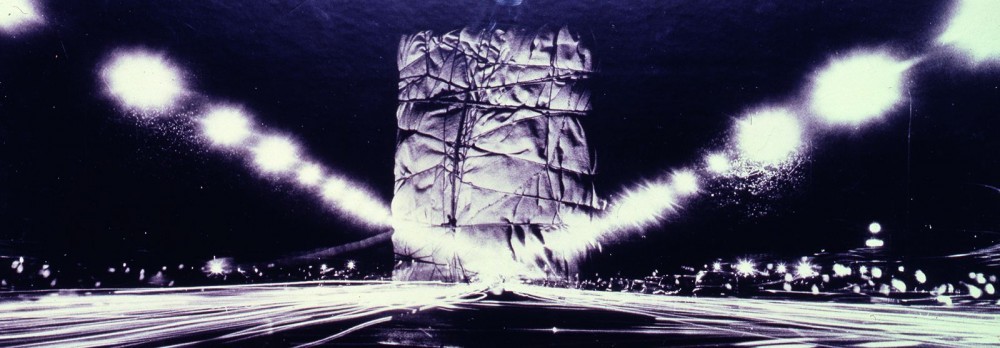

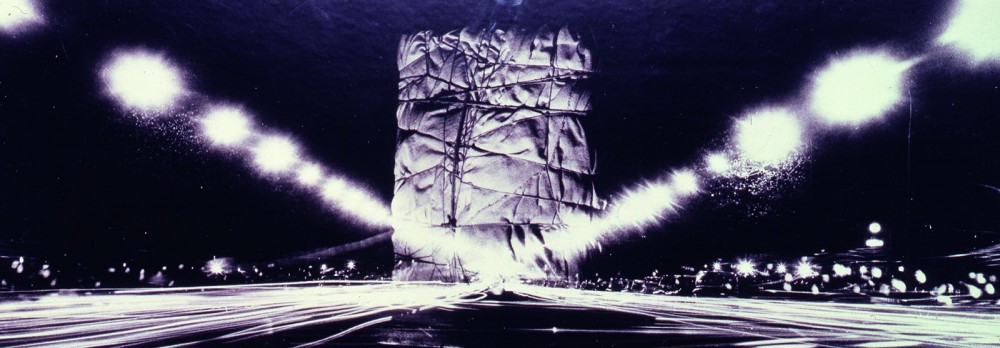

Édifice public empaqueté (Projet pour l’Arc de Triomphe, Paris) (Wrapped Public Building (Project for The Arc de Triomphe, Paris)), (1962–63); 25.2 × 70.8 cm. Photomontage of two photographs by Shunk-Kender. From the artist's collection. Photo by Shunk-Kender. © Christo

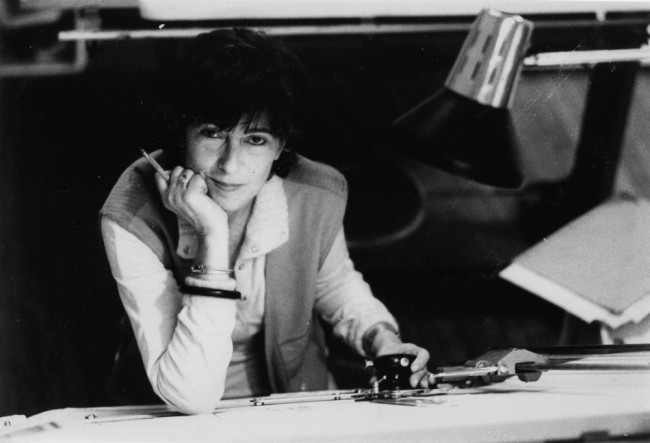

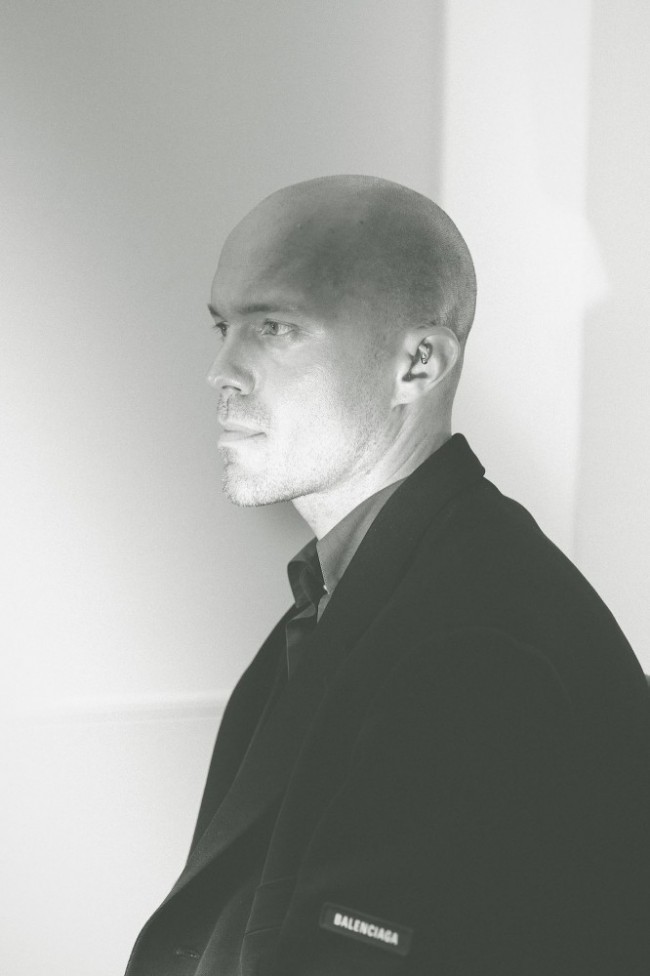

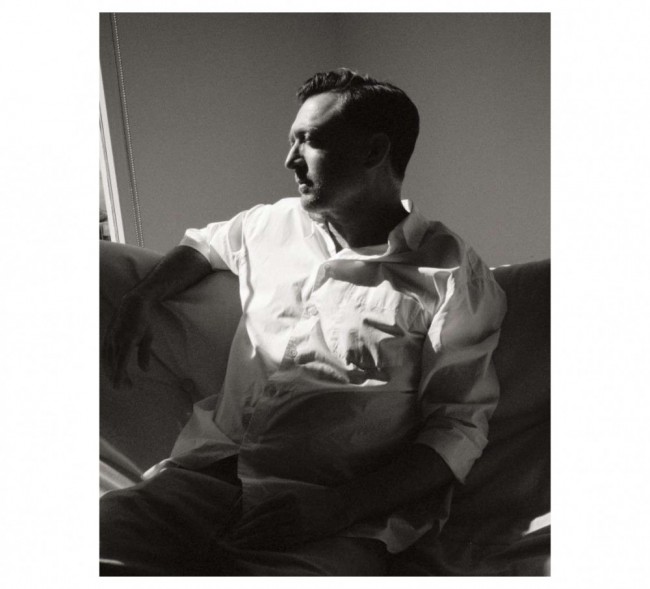

The exhibition opens with a portrait, a rather overwrought daub in the style of the times (think creepy painted ancestors in a Vincent Price horror flick), an example of the commercial work that Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, as he was born, did to survive when, in 1958, he arrived stateless in Paris after escaping from communist Bulgaria, the country he would never again call home. The sitter, Countess Précilda de Guillebon, wife of French Liberation hero General Jacques de Guillebon, had seen Javacheff’s work exhibited at her high-society hair salon, and insisted on meeting the artist. Little did she know that, through her unwitting entremise, one of the great art partnerships of modern times would be born. For madame la comtesse had a daughter. Her name: Jeanne-Claude.

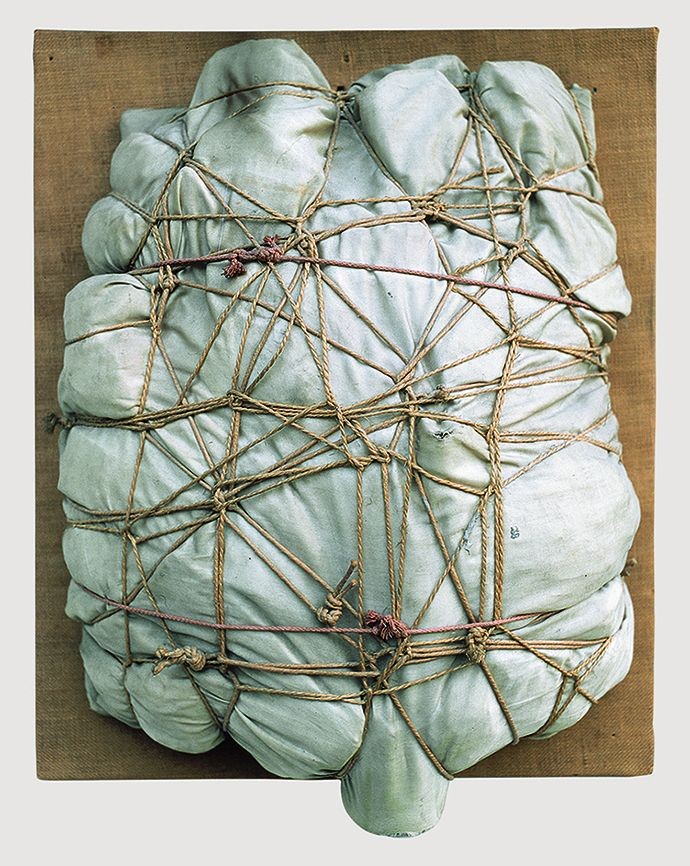

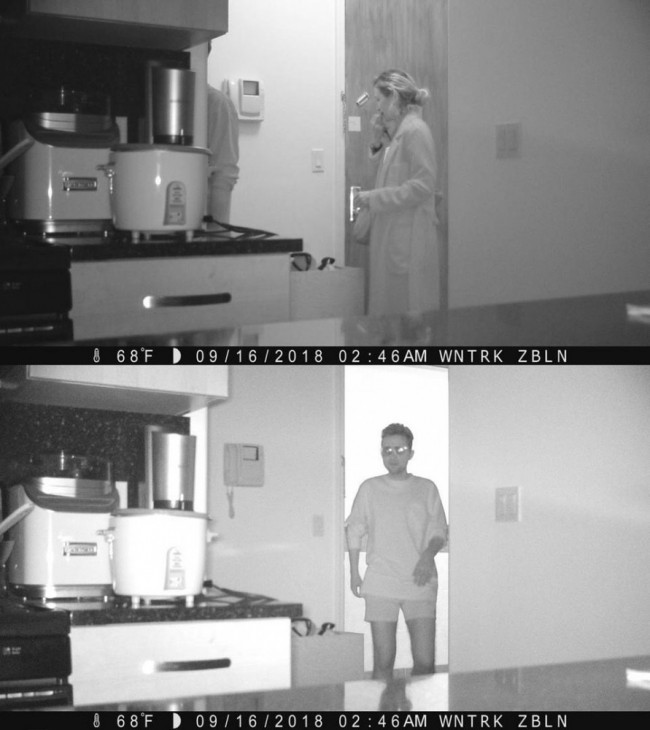

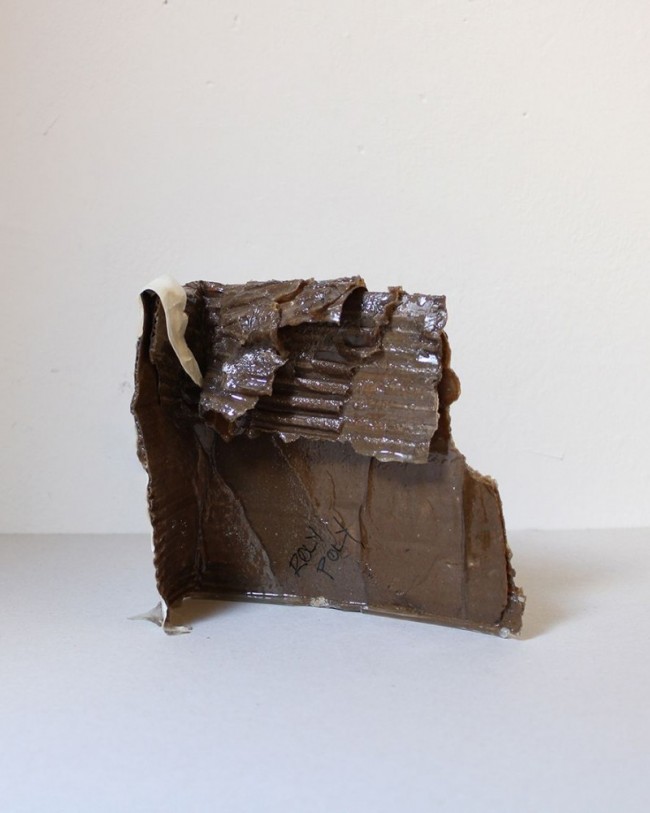

Empaquetage (Package), (1961); 47.5 × 42.5 × 22.8 cm. Fabric, string, cord and various objects on panel. From the National Gallery of Art, Washington, Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection, 1999.4.1. Photo by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, NGA Images. © Christo

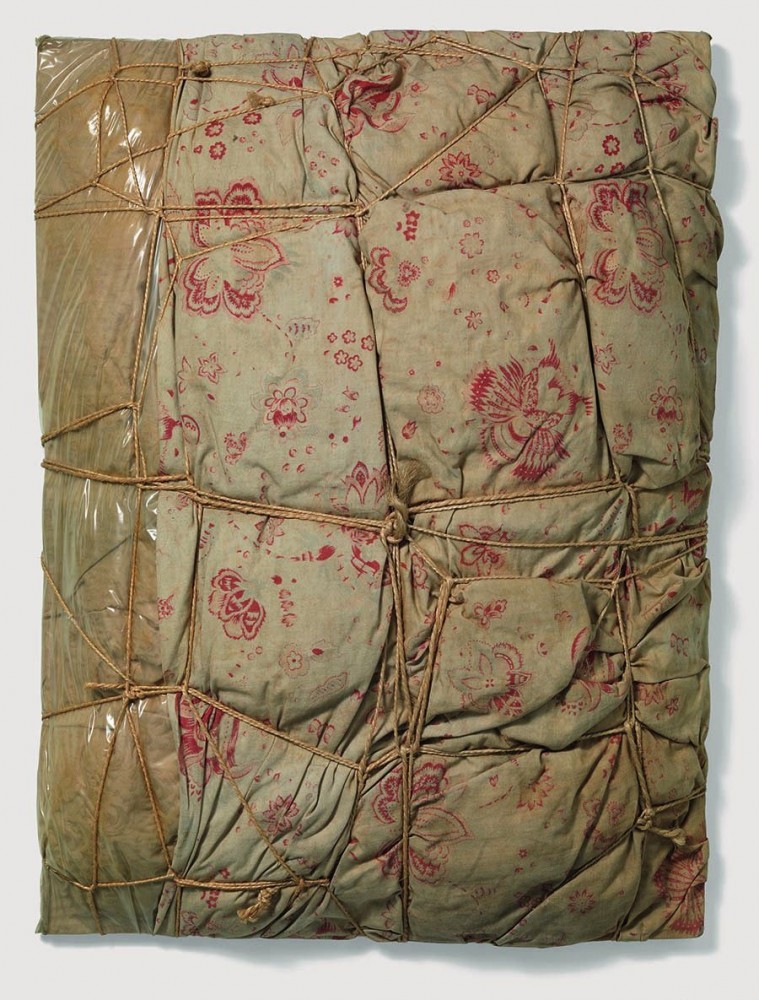

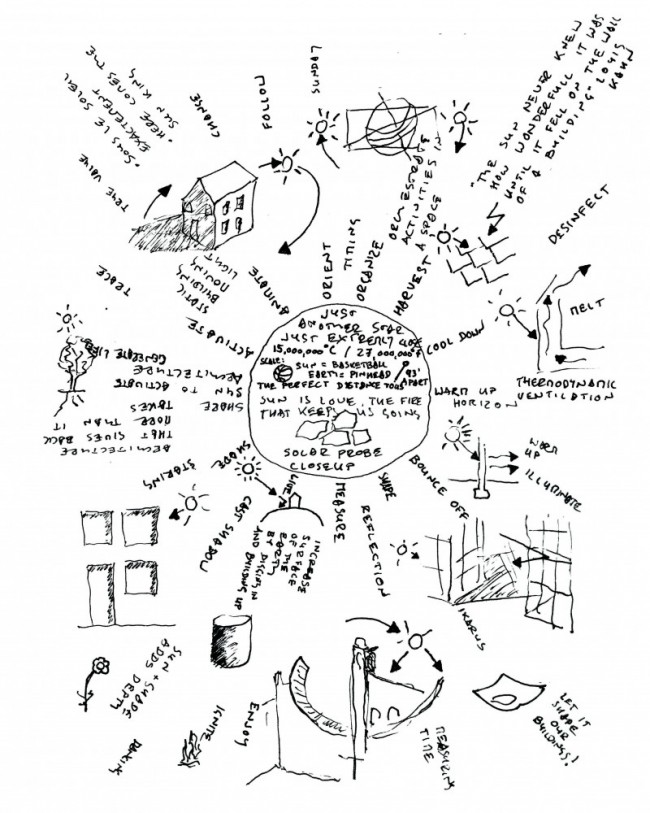

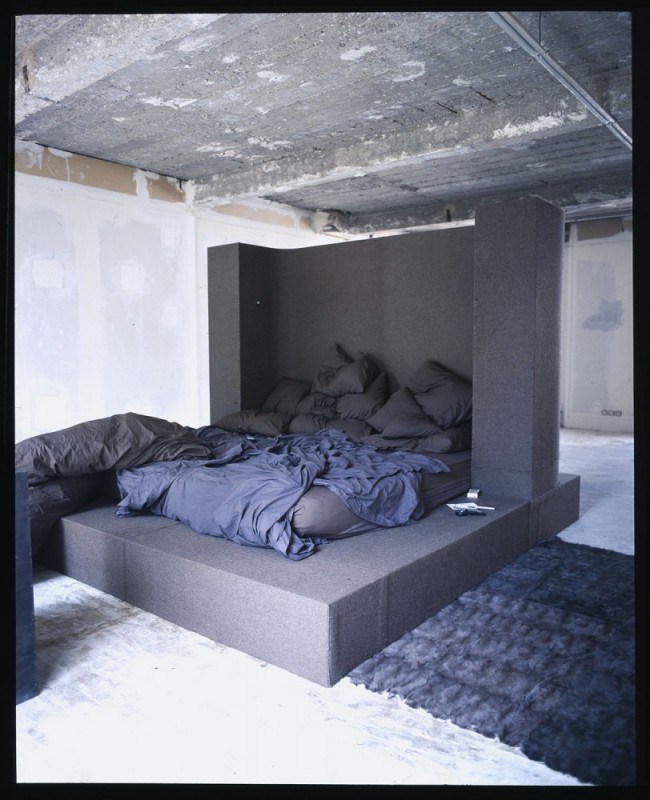

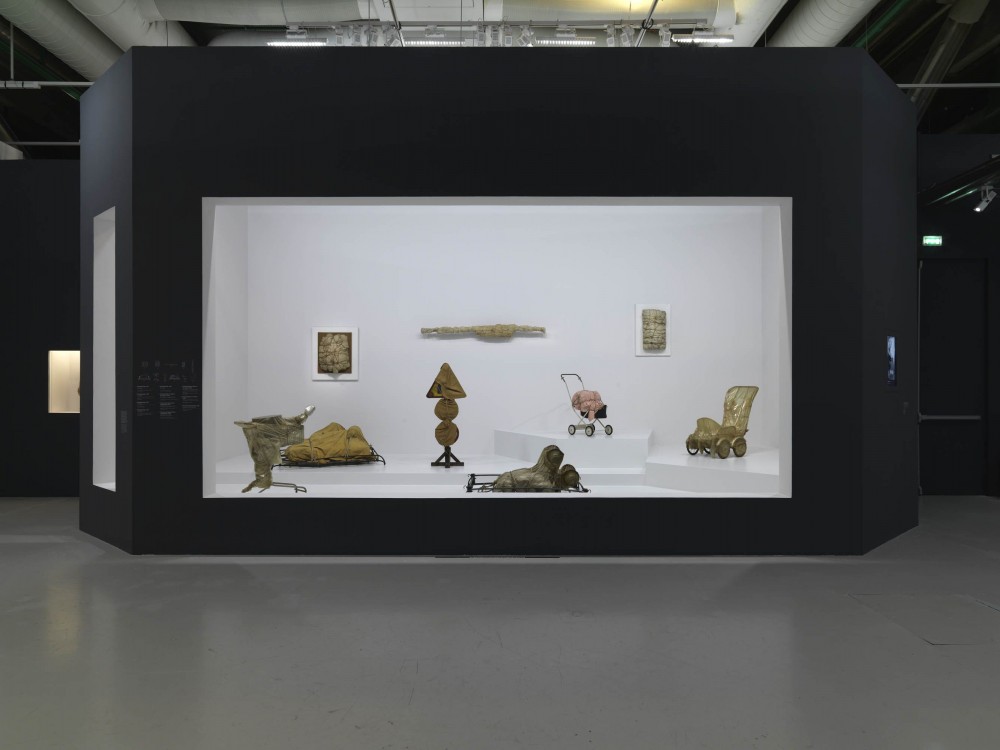

When they first met, the penniless refugee signed his commercial work Javacheff, but used just his first name for the pieces he considered serious. She later recounted with delight the occasion when, early in their relationship, she feared she might be dealing with a psychopath as, after he led her up seven floors of stairs to his chambre de bonne, the timed lighter in the hallway clicked off just as he opened the door and she crossed the threshold into a dimly lit room filled with the strangest packages wrapped in cloth and string. Christo initially covered small objects, bottles, and metal boxes, although quite why he never would say. Some have read into his work a critique of our consumer society, others saw him as a neo-Dadaist playing with readymades. An ancestor of his oeuvre can be found in Man Ray’s Surrealist sculpture L’Énigme d’Isidore Ducasse (1920), a mysterious object tied up in cloth with a string (as it happens a sewing machine, although you’d never know it, a reference to Ducasse’s fêted poetic novel Les chants de Maldoror). But while Christo’s first wrapped objects were entirely dissimulated, he soon began to half-wrap objects, and later used transparent polyethylene to wrap consumer goods such as prams and chairs as well as statues and people (the latter preserved for posterity as photographs). Many of these objects appear in the Paris show, and though in photos taken at the time a buggy or a shopping trolley swathed in polyethylene still appears fresh and contemporary, in real life, nearly 60 years on, the transparent plastic has yellowed and puckered into a Pop-era Miss Havisham shroud. Time, at the Pompidou, has horribly withered those swinging sixties, Christo’s early wrapped works appearing like something from a sordid horror film. Seeing them next to their photographs is almost as shocking as looking into a mirror and seeing one’s own cadaver.

-

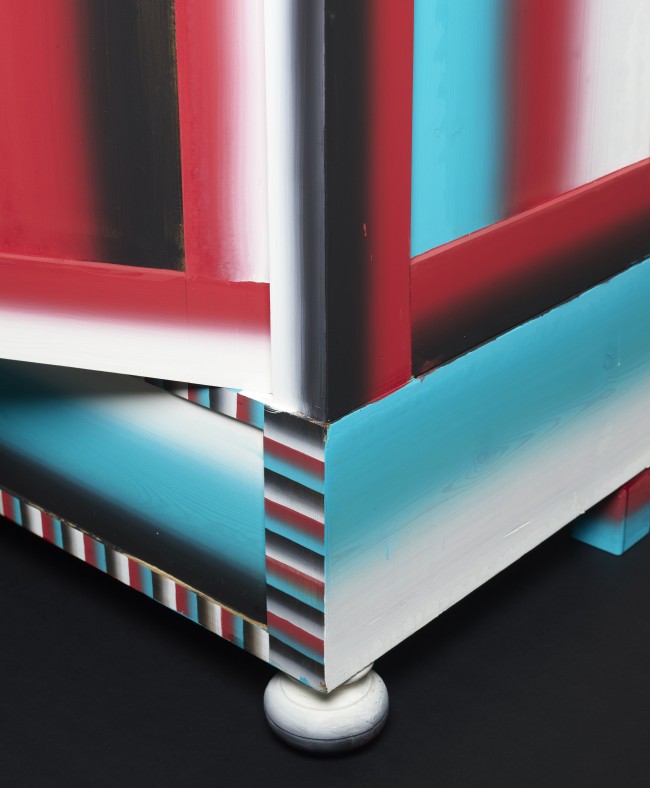

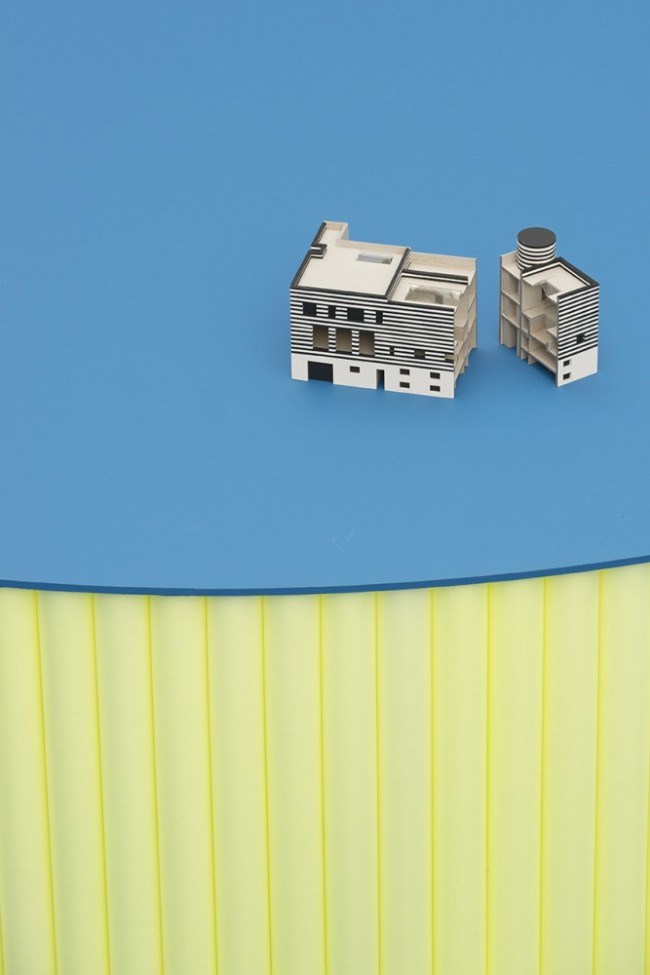

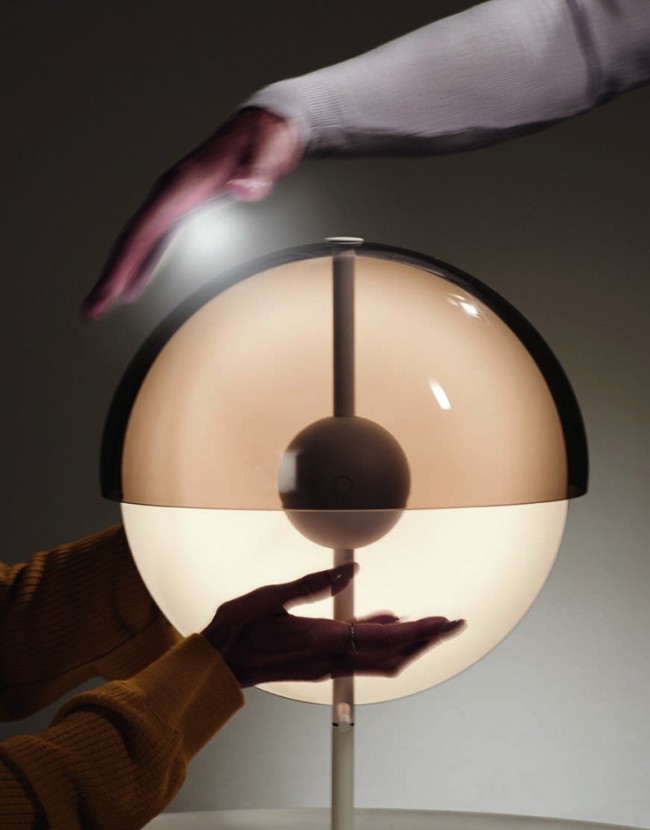

Exhibition view of Christo and Jeanne Claude: Paris! at Centre Pompidou in Paris, open from July 1 to October 19, 2020. Photo by Audrey Laurans

-

Exhibition view of Christo and Jeanne Claude: Paris! at Centre Pompidou in Paris, open from July 1 to October 19, 2020. Photo by Audrey Laurans

-

Exhibition view of Christo and Jeanne Claude: Paris! at Centre Pompidou in Paris, open from July 1 to October 19, 2020. Photo by Audrey Laurans

-

Exhibition view of Christo and Jeanne Claude: Paris! at Centre Pompidou in Paris, open from July 1 to October 19, 2020. Photo by Audrey Laurans

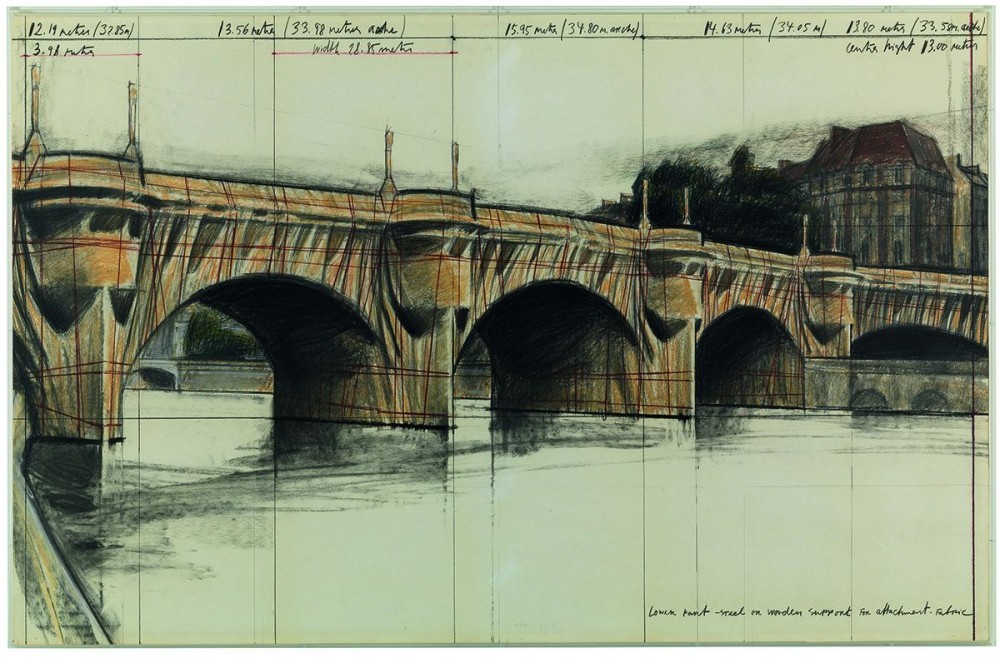

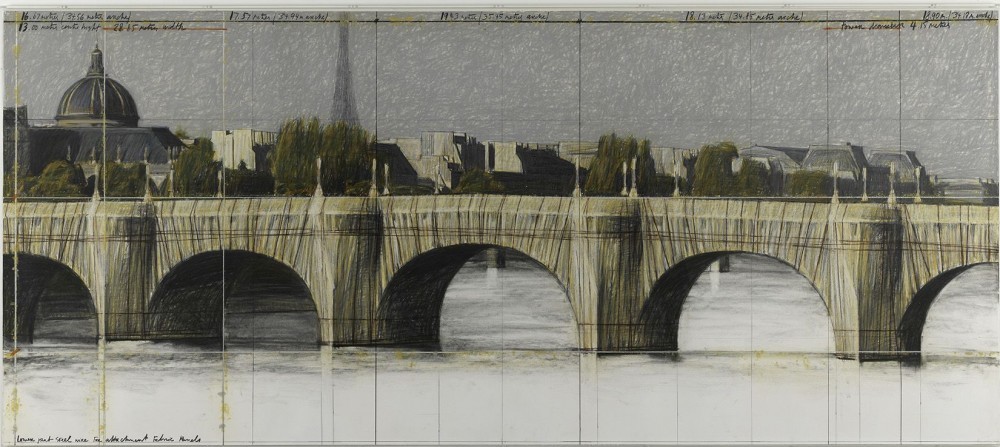

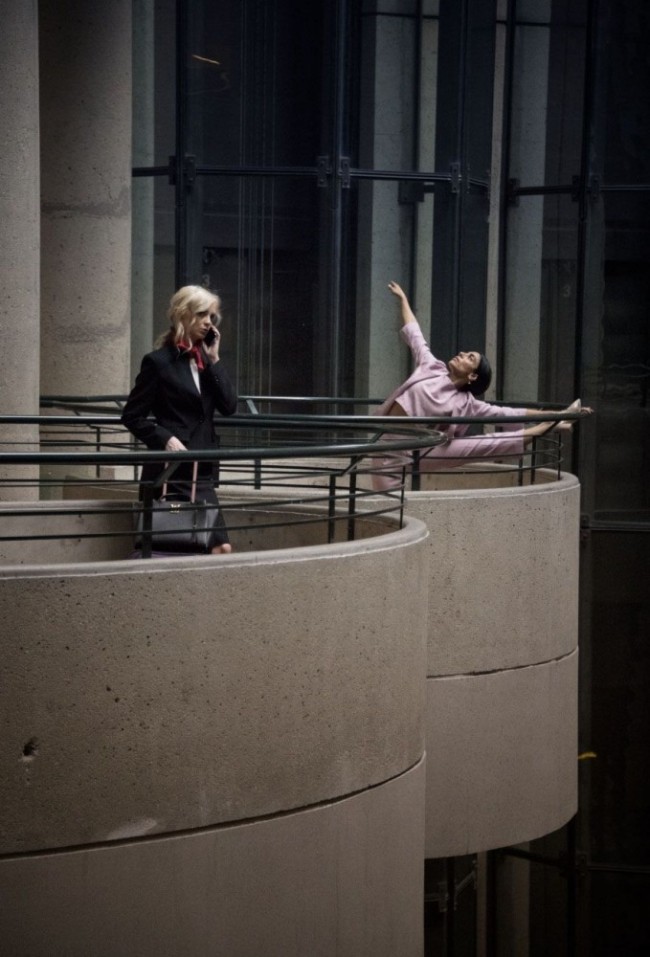

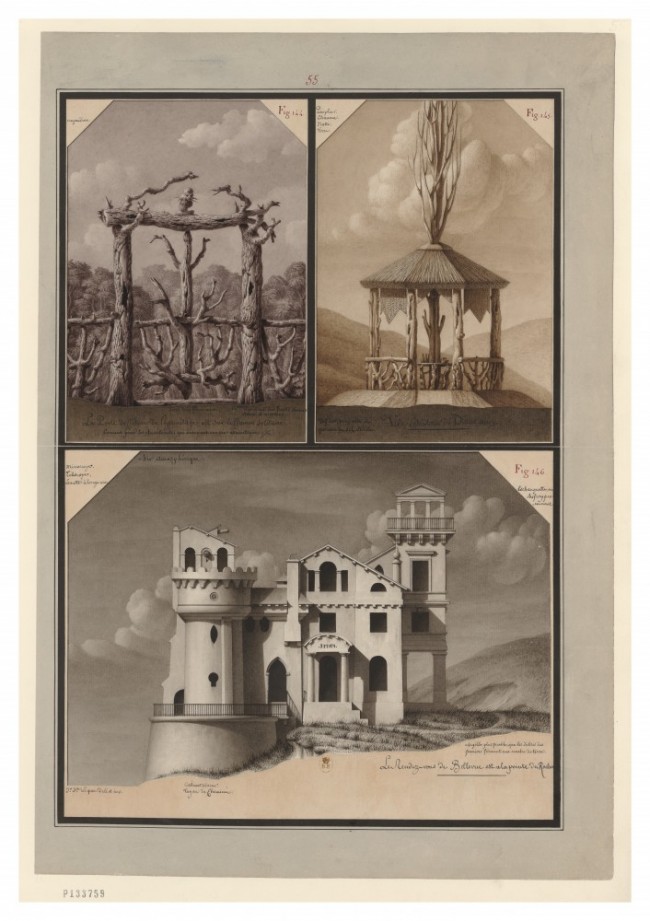

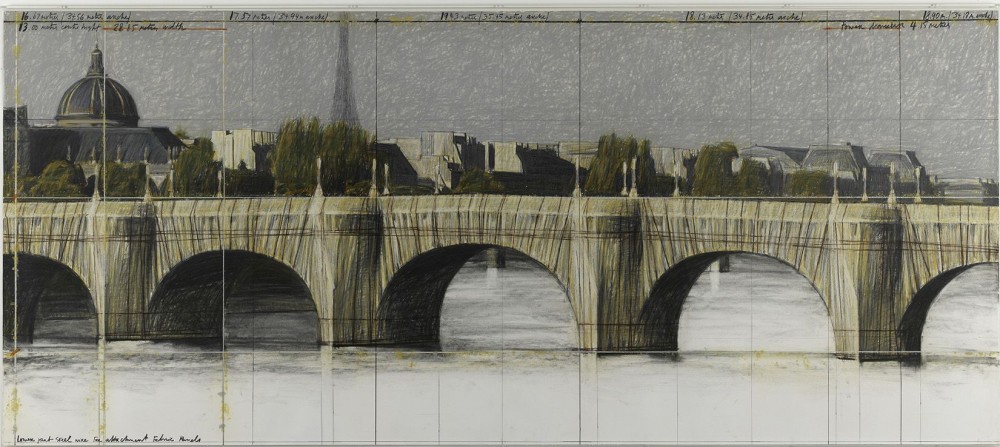

Christo came up with the idea of wrapping buildings very early on — the plan to cover the Arc de Triomphe dates back to at least 1962 — but the practical obstacles meant that decades would often pass before the work could be realized. It was Jeanne-Claude’s charm, chutzpah, connections, and organizational skills that made it all happen, as becomes clear in the second half of the Paris exhibition, which is dedicated to the 1985 wrapping of the Pont Neuf. This show within a show, assembled by Jeanne-Claude and Christo themselves, documents the decade-long process to bring the project to fruition. “For me aesthetics is everything involved in the process — the workers, the politics, the negotiations, the construction difficulty, the dealings with hundreds of people,” Christo told The New York Times in 1972. “The whole process becomes an aesthetic — that’s what I’m interested in, discovering the process. I put myself in dialogue with other people.” This is precisely what is on display at the Centre Pompidou, in the form of countless preparatory drawings, maps, tables of technical data, photographs, and some of the unthinkably voluminous correspondence required to get the thing off the ground: letters exchanged with Jacques Chirac, then mayor of Paris, with Jack Lang, France’s culture minister at the time, with contractors and lawyers, and also with the Prefect of Police, who, two months before the scheduled wrapping, was still refusing to give his formal approval. At the heart of this section is a must-see 1990 documentary by Albert and David Maysles (of Grey Gardens fame) entitled Christo in Paris: at times moving and at others hilarious, it shows us all the main players: a reluctant Chirac, worried about reelection, General de Guillebon, suave, cynical, and savvy, Lang, who got it straight away and could see, despite others’ skepticism, both the immediate political benefit and the grander picture, and, on the day of the inauguration, Madame de Guillebon herself as fairy godmother. But the film also illustrates the “love story ... between a refugee artist and a French general’s daughter,” as the filmmakers’ promotional blurb has it, set on “the oldest bridge in Paris — the same bridge where Christo courted Jeanne-Claude.” Being from a wealthy privileged background, Jeanne-Claude was not expected to marry a penniless Eastern European refugee. Indeed she first married someone else, whom she left after just three weeks, still enamored of Christo. “I had money and Christo didn’t,” she says to the camera. “I had never used my money for anything very exciting. But Christo, with no money, could offer me a very exciting life.”

-

The Pont-Neuf Wrapped (Project for Paris), (1985); 106.6 × 244 cm. Pencil, pastel, charcoal, wax crayon, ink prints and glue on paper mounted on cardboard in a Plexiglas vitrine frame. From the artist's collection. Photo by Philippe Migeat. © Christo

-

The Pont-Neuf Wrapped (Project for Paris), (1975–85). Photo by Wolfgang Volz. © Christo

-

The Pont-Neuf Wrapped (Project for Paris), (1975–85). Photo by Wolfgang Volz. © Christo

The Pont Neuf Wrapped lasted just two weeks, but 3 million people — a stupendous figure in an age before budget flights — came to see a work that marked the imagination of a generation. Jack Lang, spot on as ever, said, “Never did anyone look at the Pont Neuf as much as on the day that it was hidden. Christo teaches us to see.” As enigmas, Christo’s first wrapped pieces remained essentially mute, which is no doubt why he moved on to half-wrapping his pieces, thereby allowing the objects to be both recognizably themselves and something else, enriching the experience. With his wrapped buildings, he squared the circle. Though they are entirely dissimulated in the manner of Man Ray’s L’Énigme d’Isidore Ducasse, there is no longer any enigma in the sense that the audience knows exactly what the objects are and what they look like from having seen them so often, whether in real life or in paintings and photographs. By veiling landmarks from our gaze Christo turned the process of unveiling an artwork on its head, allowing us to experience them anew.

Portrait empaqueté de Jeanne-Claude, (1963); 78.5 × 51.1 × 5.1 cm. Polyethylene, rope, oil on canvas signed Javacheff, mounted on painted wooden board. From the Collection Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego; Gift of David C. Copley Foundation, 2013.50. Photo by Christian Baur, Basel. © Christo

When Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapped their first building in 1968 (Bern’s Kunsthalle), public reaction was skeptical. Twenty-seven years later, when they wrapped the Reichstag, they had become a globally popular art phenomenon. Critics were divided, many accusing them of vacuity: “Whether it was ‘art,’ (the public) neither knew nor cared,” wrote The New York Times’s John Russell in 1985 of the wrapped Pont Neuf. “If it was fundamentally vacuous, nobody complained. It was something to look at, something to walk on, and something to think about.” But surely there was always more to it than that. If Christo fled Bulgaria, it was because he resented the narrow definition of art that held sway there, nor the fundamental dishonesty of much Socialist Realism, which painted an idealized picture that was little more than propaganda. In 1962, he and Jeanne-Claude realized one of their first public-space works, an unauthorized intervention in Paris’s very narrow rue Visconti, which they blocked with piled-up oil barrels (a symbol of the modern world and its problems if ever there was one). Entitled The Iron Curtain, it was Christo’s reaction to the Berlin Wall, which he had seen go up a year earlier in 1961, but also an echo of Paris’s revolutionary barricades, erected in the name of fairness and freedom. In Bulgaria, Christo’s father was tried and imprisoned for sabotage, the “intentional destruction of Soviet production,” after a drunken worker at the factory he managed to accidentally destroy 100,000 meters of fabric by overbleaching it. When, after the fall of the Soviet Empire, Berlin was reunited and Christo and Jeanne-Claude at last wrapped the Reichstag, they used exactly 100,000 square meters of polypropylene fabric. Moreover — if the official narrative is to be believed — the artists self-financed all their interventions through the sale of related works, refusing grants and sponsorship so as to keep their art autonomous and free. If art has to be about anything, Jeanne-Claude and Christo’s was about liberty — the freedom just to do it, and to do it gratuitously, generously, and gloriously.

Text by Andrew Ayers

All images courtesy of Centre Pompidou, Paris.