LAND ARTISTIC: Yorkshire Sculpture Park’s New Visitor Center by Feilden Fowles

The Weston, the new gallery space and visitor centre at Yorkshire Sculpture Park in the north of England, can be understood as an architectural exploration of duality. A relatively simple project in terms of program, scale and site, there is nonetheless a rich attention to detail and intelligent engagement with context in-keeping with the previous work of the project’s young, London-based architects Feilden Fowles.

The Weston visitor centre at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Exterior view of restaurant. Photo by Peter Cook.

The park itself is a 100-hundred-acre slice of 18th-century landscaped countryside, once the grounds of Bretton Hall, dotted with original follies, pavilions, bridges and a lake, as well as modern sculptures and gallery buildings that have been added to the landscape since the sculpture park’s opening in 1977. Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Bob and Roberta Smith, James Turrell, Anthony Gormley, and Ai Weiwei are among the artists with pieces on display to Yorkshire’s inclement weather and the park’s 500,000 annual visitors.

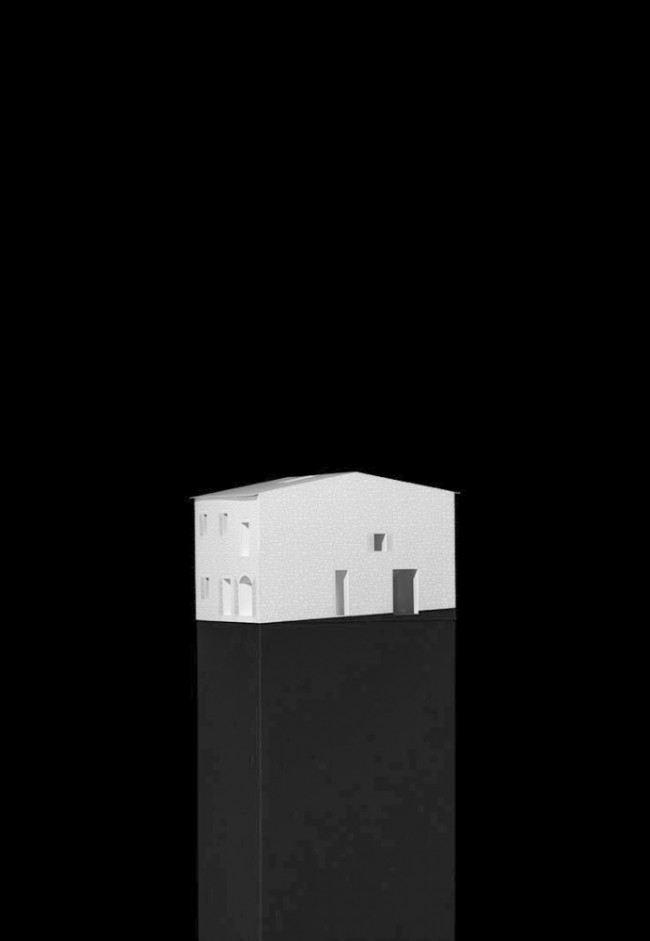

The Weston visitor centre at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Photo by Peter Cook.

It was inside Turrell’s Deer Shelter Skyspace (2007), a deer shelter converted to frame the sky above through a simple square aperture, that Fergus Feilden and Edmund Fowles contemplated how to fit a new piece of architecture onto a site loaded with natural and cultural reference points. “What is sculpture? And what is the relationship between sculpture and architecture? How would we embrace those two things?” mused Fowles at the project’s opening.

-

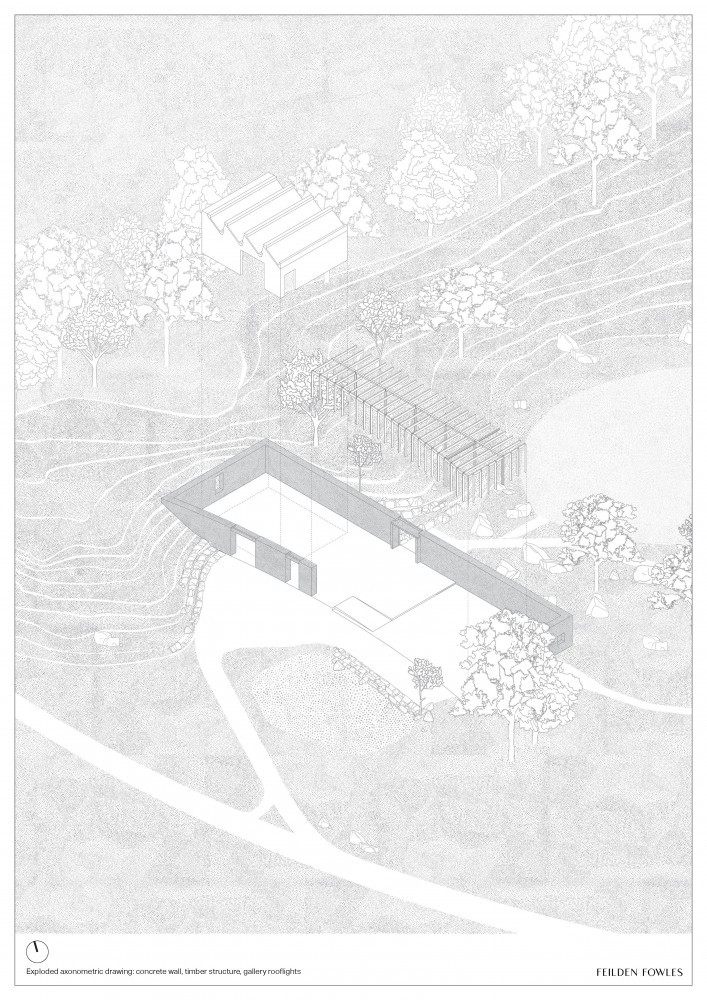

Weston visitor centre at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Axonometric plan. Courtesy Feilden Fowles.

-

Weston visitor centre at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Ground plan. Courtesy Feilden Fowles.

-

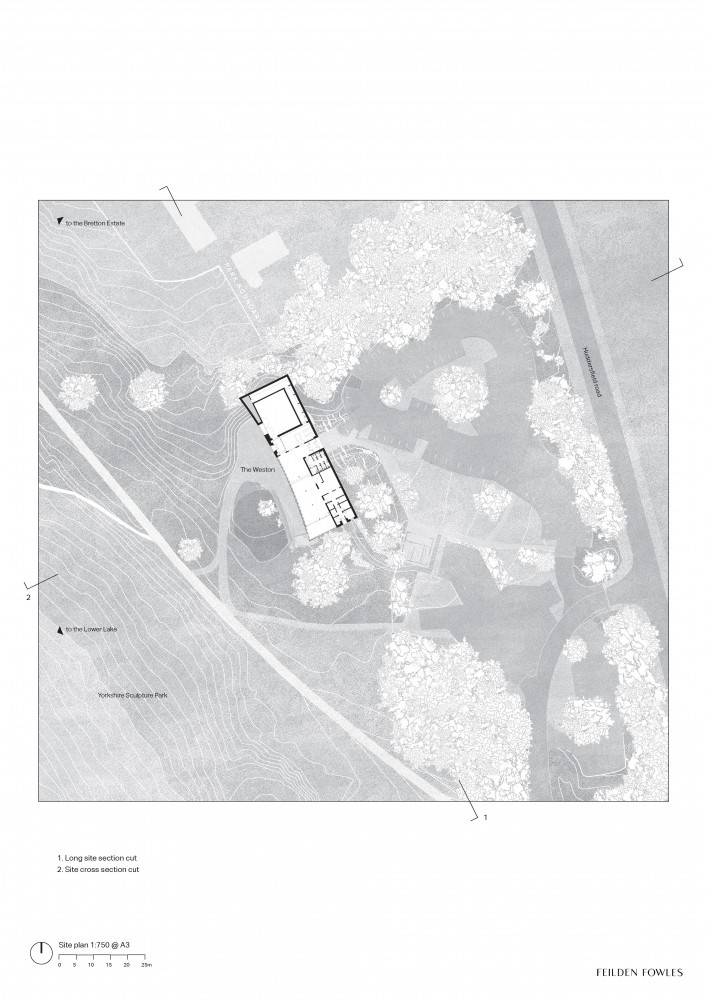

Weston visitor centre at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Site plan. Courtesy Feilden Fowles.

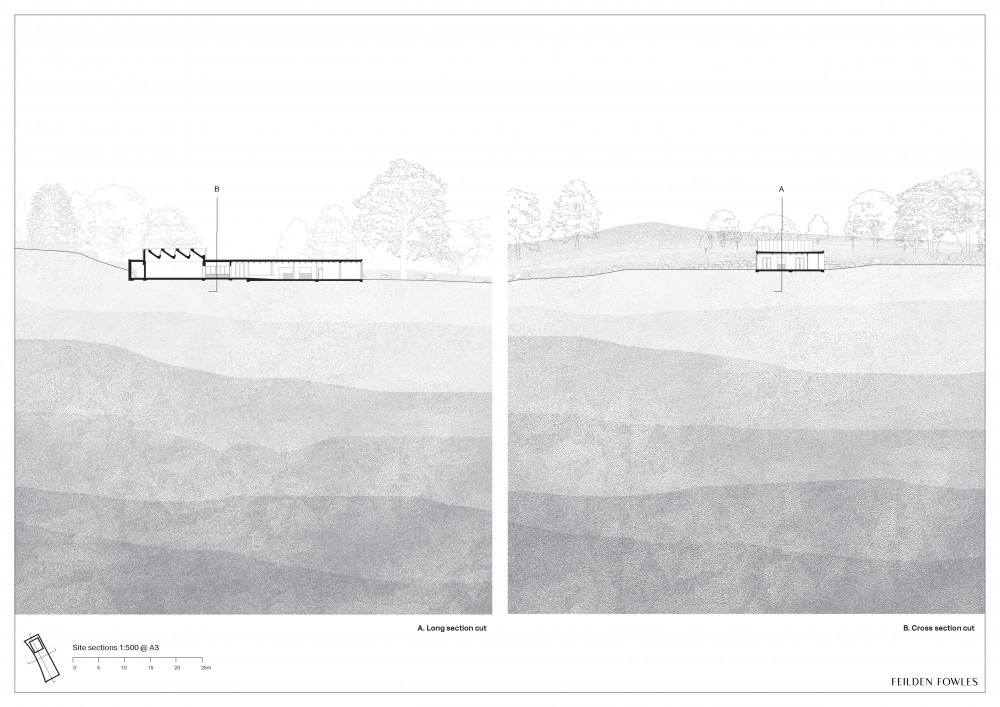

The resulting structure is more Robert Morris earth mound than Henry Moore on a plinth, informed by the architects’ long-term interest in the land artists of the 1960s and 70s, Morris and Michael Heizer among them. Indeed, the rectilinear form of The Weston seems to emerge out of the Yorkshire hillside, on a former quarry site, as though its the positive relief to Heizer’s Double Negative, cut out of the Moapa Valley in 1969.

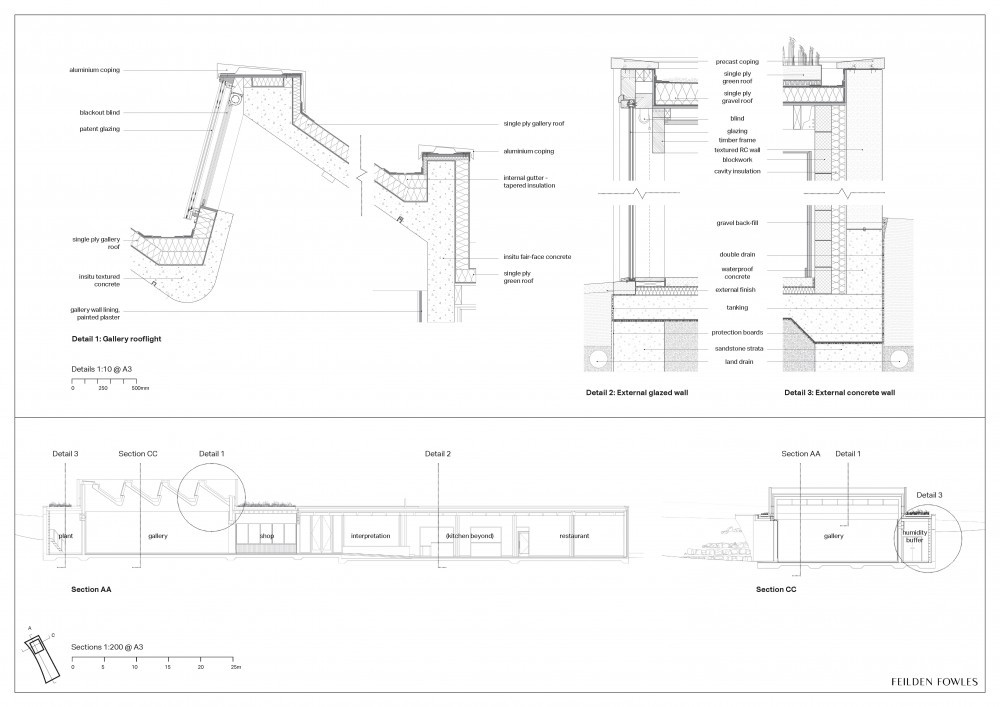

Approaching from the east, with the M1 motorway behind, The Weston is first experienced as a “monolithic wall,” in Fowles’ terms. A single entranceway punctures the wall, through which visitors are filtered before the park’s landscape is unveiled by the fully glazed western facade of the single-story, 673 msq building. The building’s frontier character, between the infrastructural noise to its east and the Arcadian landscape to its west, is echoed by the building’s own internal split between an expressive gallery space and more muted visitor centre. The visitor centre, complete with cafe/restaurant, gift shop and in-built cast-iron fireplace, is contained within a simple timber frame, giving it the air of a sleek Nordic retreat. In contrast, the gallery space is more rugged with its saw tooth roof elaborated in board-form concrete, above white walls “like a stretched canvas around the gallery,” says Fergus Feilden.

-

The Weston houses rotating exhibitions of 20th- and 21st-century artwork, complimenting the park's outdoor collection. Photo by Peter Cook.

-

Exterior view of the Weston's restaurant. Photo by Peter Cook.

-

The Weston's restaurant is contained in a timber-framed glass box that looks out onto the park. Photo by Peter Cook.

-

Weston visitor centre at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Interior view. Photo by Peter Cook.

Passing through the glazed door leading from the gallery to a patio and the park beyond, the weight and character of that monolithic wall becomes most apparent. Having investigated the geological history of the park and its surroundings, the duo developed an aggregate made from local stones to give the project walls their sandy, almost pink, hue. Above the gallery, a corrugated GRP screen filters light into the space by day and creates a lantern by night, while adding some sculptural dynamism to a relatively calm exterior.

At a time in which we, humans, must reframe our relation to the natural world, a sculpture park is a good place to begin. Here, where landscaping devices such as ha-has survive as early markers of human attempts to master — cut, mould, trim, sculpt — the form of our environments, and where some sculptures can appear like rigid markers of the divide between nature and culture, what can be the role of the contemporary architect?

The west façade is covered with a timber glazed screen, providing a barrier against the highway as well as a view out across the sculpture park.

At The Weston we begin to see some answers. Feilden Fowles’ project exhibits an impressive intellectual investment in the material and form of the natural world which is incorporated, in a manner akin to a Turrell installation, into the project as a source of inspiration, rather than exploitation. The split between nature and culture is still there, but it’s as though the architects have picked it up to look at it, to work out what it means in 2019 and how, in the words of artist Richard Wentworth, writing about the project for a newly published book, “to be present whilst being absent.”

Text by George Kafka.

All images courtesy Feilden Fowles.