INTERVIEW: Carson Chan on Climate Crisis and the Challenge of the Architectural Canon

Carson Chan in his MoMA office photographed by Maria Fonti for PIN–UP 31.

For curator, writer, and educator Carson Chan, architecture’s impact on the environment is not simply a question of how buildings produce greenhouse gases. “It’s about understanding where materials come from, how they were sourced, what the labor conditions are during construction. It’s about engaging with the historical, political, social, economic, and racial context of the site. It’s about designing the afterlives of the building. Where do the materials go? Can they be reused or repurposed?” These are the kind of questions he will be addressing as the inaugural director of MoMA’s Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and the Natural Environment, a new research endeavor dedicated to shaping the discourse on architecture and ecology. Chan, who was born in Canada and holds degrees from Cornell and Harvard, lived for over a decade in Berlin, where in 2006 he co-founded PROGRAM, an art and architecture non-profit. He was later co-curator of the 2012 Marrakech Biennale and executive curator of the 2013 Biennial of the Americas in Denver. A few months into his new MoMA position, the 41-year-old sat down with architect and artist David Tasman to discuss a wide range of topics, from his early interest in ecology and his experiences in exhibition making to his platform for climate activism (@climatelockdown) and the need to challenge the architectural canon.

David Tasman: Have you always been interested in exhibition-making?

Carson Chan: Yes. I curated my first exhibition at Cornell University in the student-run gallery in the architecture school. Around 2000, I read an article in Surface magazine about emerging designers in the New York fashion scene and got the idea to get in touch with Joseph Quartana and John Demas of Seven New York boutique and, with their help, I invited designers Benjamin Cho, As Four, and Pleasure Principle to Ithaca to exhibit their work. The process of developing the idea for the show, inviting the exhibitors, designing the displays in the gallery, announcing the exhibition, and organizing the opening gave me insight into the appeal of exhibition-making. It was a way of conveying ideas by convening various publics in a space. It required that there was an interested public and they made their interest known by showing up. As this first show was in an architecture school, it seemed obvious that architecture could benefit from this form of intellectual broadcast. The question of how we make architecture exhibitions was the focus of PROGRAM in Berlin.

When did you first become interested in environmental issues?

I became deeply invested in the environment in the first year of my doctoral studies at Princeton in 2014. I’d been studying architecture exhibitions for a while, and because I’d been living in Berlin for a decade by then, I applied with a proposal about early-20th-century German architecture exhibitions, in particular the work of Ludwig Hoffmann. But then I took several classes on environmental history and, through those, found that aquariums combined my interest in exhibitions and the nonhuman world. So I changed my topic to the history of postwar American public aquariums. They are exhibitions of nature, and I’ve come to see them as microcosms of how humanity endeavors to control the planet’s ecosystem. Well-managed aquariums give us the sense that, with enough technology and diligence, we can create a balanced, thriving community. They epitomize the dream of total control over nature. I’m particularly interested in the postwar moment in the U.S. because this was the context for the rise of the environmental movement. How did architects design buildings that were meant to focus our attention on the environment at the very moment the term was being redefined, contested, and protested?

How does this thinking inform your new role at MoMA’s Ambasz Institute?

I see my work at MoMA very much as a continuation, or amplification, of my previous engagement with architecture and the environment. In fact, I would like to critically re-evaluate what we mean when we discuss both architecture and environment. Buildings generate almost 40 percent of the world’s yearly greenhouse-gas emissions. The relationship between these categories is not neutral — it requires all our immediate attention if we want to stay on this planet much longer.

Carson Chan in his MoMA office photographed by Maria Fonti for PIN–UP 31.

What about your audiences at MoMA?

I’ve always been mindful of the various audiences I’ve created exhibitions for. As a U.S.-educated Hong Kong-Canadian living in Germany, what I communicated, how I did it, and who I was communicating to were always front of mind. I code switch when I make exhibitions in Berlin, Marrakech, Denver, or Oslo. I’ve worked in several formats. A biennial cannot possibly address the same things as an exhibition in a gallery or even a museum. MoMA has the attention of people from all levels of knowledge and interest. I’d love to engage everyone from tourists and children to scholars and other museum professionals. Public education about the climate crisis should aim to reach as wide an audience as possible. This is the hope at least, and all the work the Ambasz Institute produces will be accessible online. Interviews with architects working on ecological issues will be made available on MoMA’s YouTube channel, for example, while closed summits addressing environmental or climate issues in architecture schools can be held on Zoom.

MoMA, like many large institutions, has its own evolving sustainability mandates. Is this something the Ambasz Institute will be involved in at an operational level?

Yes, absolutely — working with the museum’s existing efforts at becoming more sustainable, including making some difficult changes in the curatorial process. That will all be an important part of the institute’s work. I’ve started conversations with colleagues at MoMA as well as at other institutions around the world to develop a method of sustainable curating. In the grand scheme of things, making museum exhibitions is not the most polluting activity in the world, but there’s no reason why it should contribute to the thoughtless destruction of the ecosystem. At MoMA, we’re switching from making new walls for every exhibition to a system that re-uses walls for up to ten years. The Ambasz is at heart a research institute aimed at advancing knowledge about the so-called built and natural environments, but, as an entity within MoMA, I want it to help transition other aspects of the museum into sustainable operations. The MoMA Design Store, for example, is an incredibly important interface between the museum and the public. I’m already working with them to investigate circular-economy products — things that will never see a landfill. The logic of ecology, of interconnected reliance, means that issues need to be addressed from many different angles: the source of materials, labor conditions, the historical, political, social, economic, and racial context of the site, as well as the building’s afterlives.

What does an equitable architectural landscape look like?

Architecture, unlike, say, music, writing, or drawing, often requires large sums of money. You can write a book or play a guitar without much money, but you can’t build buildings unless you have access to power. Because of this, architecture, especially in the global North, is not only intimately connected to systems of exploitation but also often enables the unequal treatment of minority communities. The structures of white supremacy, as Raoul Peck retells it in his recent documentary series Exterminate All the Brutes, are tied to the project of Western imperialism, and architecture has been instrumentalized to perpetuate it. France, for example, exploited Haiti’s resources and people, enslaving them to deforest land to grow sugar cane and coffee for French gain. France charged Haiti the equivalent of 21-billion U.S. dollars in 1825 for independence, effectively ensuring that generations of Haitians would be in debt and unable to prosper. Architecture, in this case, is not only the French cathedrals, forts, and government buildings still in Haiti today, but also the enduring changes to the lived environment caused by deforestation and soil depletion.

What changes you would like to see?

Well, to paraphrase Walter Mignolo, you can’t decolonize the museum or the university in the West, but you can do decolonizing work within them. Real change needs to be systemic. We need new leaders and educators who have lived experience of difference. We need to do away with the canon and recognize that multiple histories and multiple perspectives are valid.

Carson Chan in his MoMA office photographed by Maria Fonti for PIN–UP 31.

In your 2020 film Notes on Fortnightism, which you made with Gustav Düsing, the narrator states that “the global development of viral spread is hard to predict. An architectural response needs to be like a virus: adaptable, mobile, scalable, and resilient.” What brought about this project? How did your thinking evolve pertaining to architecture, the coronavirus, and the environment?

At the beginning of the lockdown, last March, Gustav and I started texting each other about the architectural implications of the pandemic. Everywhere in the news we saw field hospitals popping up, emergency care facilities being fitted into parking lots, and plastic membranes installed in nursing homes so that the elderly could hug their family without touching them. To me, these didn’t seem like viable long-term solutions. We understood that buildings — the rigid object at the center of architectural discourse — could not really respond to these bizarre bits of genetic material we call viruses. Early in the pandemic, virus outbreaks would appear almost without notice unexpectedly. Facilities to accommodate quarantine, treatment, and convalescence could not appear quickly enough. In Wuhan, a 645,000-square-foot, 1000-bed hospital was built in a little more than a week. But what happens after the virus subsides? We recognized that for architecture to properly respond, it had to be like the virus. Gustav and I devised a modular building system composed of a series of tents that could house what we call a responsive care center, or RCC. It’s a facility that’s deployed through shipping containers, easy to set up and quick to pack back up, that could plug into existing utility infrastructure. The RCC is part of a larger theory we devised called “fortnightism,” a term coined with respect to the 14-day mandatory quarantine required for those who have been exposed to the virus or want to travel across borders. These 14 days lie between many categories. Mandated by the state but experienced alone, these two weeks are part private, part public, neither vacation nor work. If you add to this the randomly enforced lockdowns, then fortnightism encompasses all the ways the pandemic fundamentally changed how we encounter the world. We see it as a new variant of humanity’s spatial and temporal paradigms.

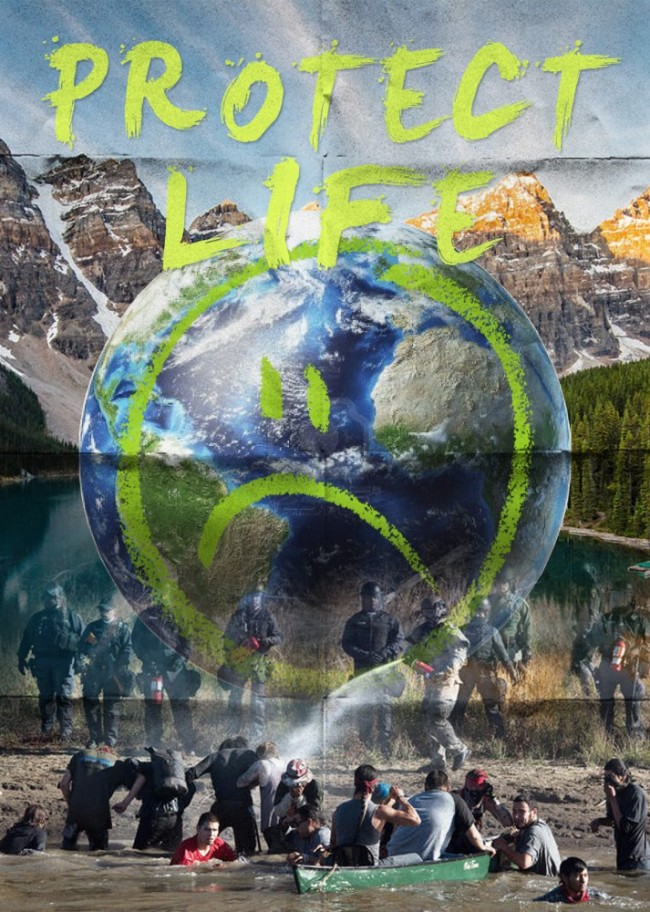

You started the Instagram account @climatelockdown in 2020. It now has nearly 20,000 followers. What is it and what prompted you to initiate it?

@climatelockdown was also a result of the pandemic lockdown, during which the Trump administration started rolling back long-standing environmental policies and safeguards. It was frustrating because the very moment we should all have been out on the streets protesting, we had to stay home. Also, I was amazed at how most people didn’t understand that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is itself a symptom of the climate crisis. It was by expanding cities and farmland, encroaching on areas that humans have never occupied before, that we encountered this pseudo-organism called SARS-CoV-2. The very moment we needed to bolster environmental protections, the Trump administration decided to weaken them. Without the ability to protest on the streets — this was before the summer of Black Lives Matter —, what if I transformed my lockdown into a protest? What if, instead of simply sitting in my living room, I was actually at a sit-in? It’s a sneaky semantic shift, but in fact most protest movements are about the mutual education that takes place before anyone is on the streets. The street protest is just a small part of it. At that point, I was consuming so much material about the intersectional relationship between the climate crisis, the pandemic, environmental racism, and how all of this is the effect of the long legacy of white-supremacist imperialism. @climatelockdown was a venue for me to share quotes from the material I was reading. In following the Instagram account, people understood that they were joining a protest movement centered on dismantling the structures that perpetuate our interconnected crises of climate, public health, and race.

Interview by David Tasman

Portraits by Maria Fonti for PIN–UP

A version of this interview was published in PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22.

Please visit the Ambasz Institute’s website for more information on Built Ecologies, a new video series produced by PIN–UP for the Ambasz Institute, aimed at drawing the general public deeper into major recent topics around architecture and the environment.