RECONSTRUCTIONS PORTRAIT: Germane Barnes on Reframing Blackness

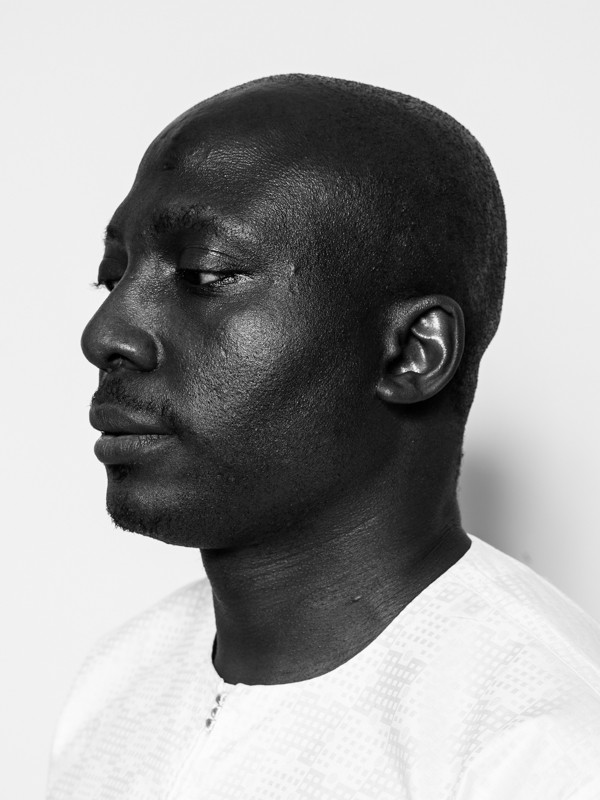

𝘖𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘔𝘶𝘴𝘦𝘶𝘮 𝘰𝘧 𝘔𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘯 𝘈𝘳𝘵, 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵 𝘋𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘥 𝘏𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘰 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘸’𝘴 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘳𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘪𝘦𝘸𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘵 (𝘴𝘦𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘰𝘸). 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗’𝘴 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘚𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘈 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘩𝘪𝘱 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘮 𝘉𝘳𝘰𝘸𝘯𝘦.

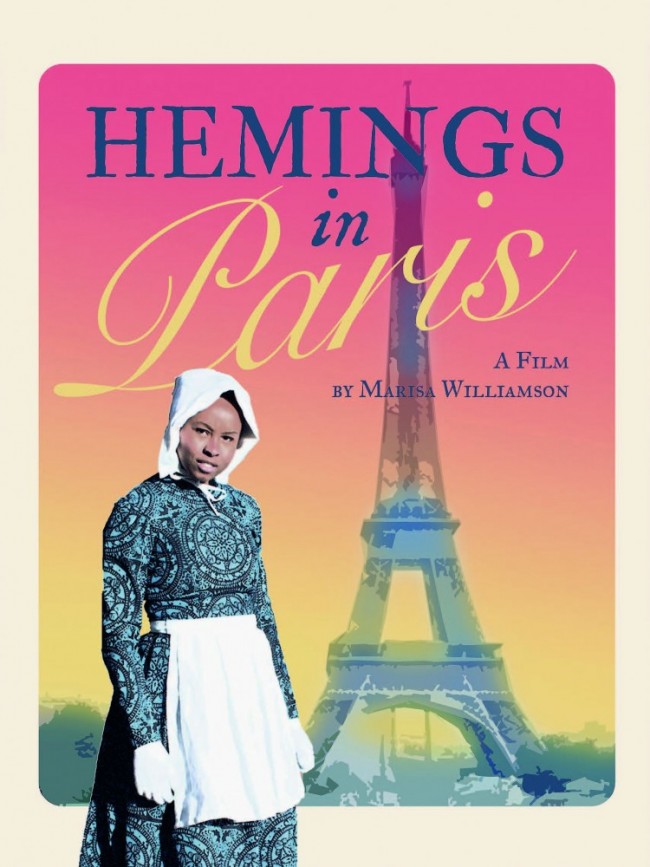

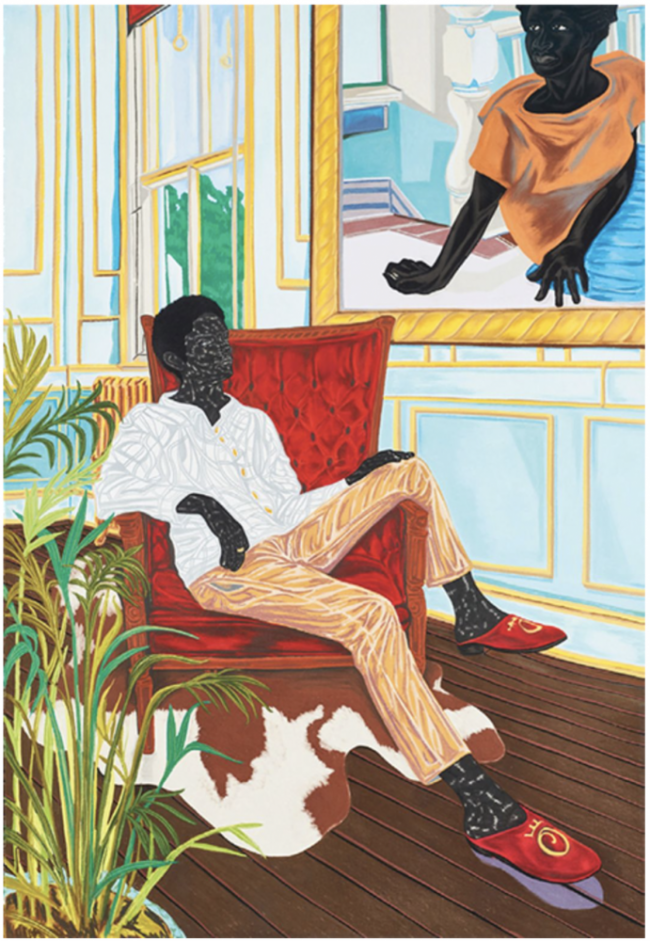

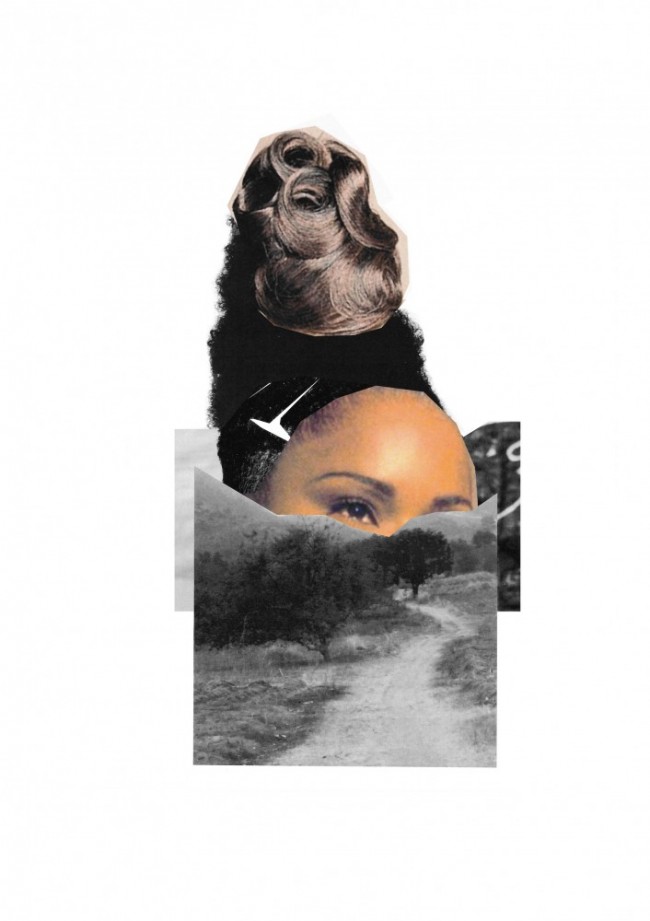

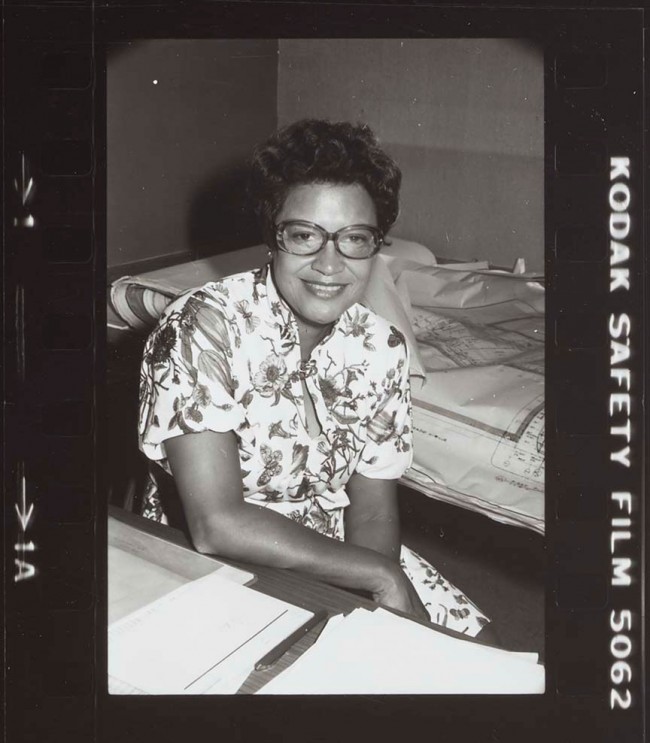

Miami-based architect, urban planner, and professor Germane Barnes uses speculation and historical research to examine the reciprocal relationship between architecture and Black domestic and city life. Through his practice, Studio Barnes, he has created pop-up porches and stoops that consider different sites of gathering and the thresholds between the home and the public, developed urban agricultural environments, and designed residential and private projects.

Germane Barnes photographed by David Hartt for PIN–UP.

PIN–UP: What led you to architecture?

Germane Barnes: To be honest, becoming an architect was really an act of defiance. My mother wanted me to be a lawyer and then a politician. I worked on political campaigns in high school, took government and politics classes at my prep school, and served on their peer jury. But I always knew I would be an architect. As a Chicago native, I was born in a culturally rich city with ample examples of influential architecture. Living in close proximity to Oak Park, Illinois certainly helped. Driving by the beautiful homes and manicured lawns definitely left an impression. My mother worked in the Sears Tower (I will never call it by any other name) when I was a child. I often played in the Holmes Elementary School fields across the street from Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio before I knew of the building’s significance. I built a model of the Guggenheim Museum in the seventh grade. If there were a person with a clear track to architecture, it was me, even though I never met an actual architect (who happened to be Black) until I was 17. I resided on the west side of Chicago in an area called K-Town. However, I attended elementary school on the far north side of the city in Albany Park via yellow school bus. I witnessed how the city and urban fabric varied based on neighborhoods at a very early age. It has certainly helped shape the way I work today.

How has your practice evolved?

Chicago, as a notoriously segregated city, has had a large hand in my practice as I am always searching for the identity and history of Black spaces. Professional and academic stints in Cape Town, Los Angeles, and Miami have only reinforced that search. In the past, I could not narrow the focus of my practice as I was trying to find and celebrate every aspect of the Black experience in the built environment. It is subject matter that is woefully absent from the field and discourse, so I tried to do it all. It was not until I began drawing from my own experiences that I understood my unique perspective in this field, specifically the Black experience at a domestic level. I am a Black man from an economically privileged family who attended the best schools in the country, but the irony is that I grew up in a neighborhood that many would deem dangerous, disenfranchised, and vulnerable. I clearly understood the difference between poverty and affluence because I lived it. I grew up in a five-bedroom home with both my parents; however, when visiting relatives, I learned how to heat bath water on the stove because there’s no hot water. It was normal to have pants tucked in socks, because it would deter pests from entering your clothes while you slept. My porch research, which started my personal trajectory of spatializing Blackness, was born of many summer nights occupying this critical space with family. It is where I had my first lemonade stand, and where I was arrested for “mistaken identity.” My practice’s sole goal is to use architecture as a griot because there are so many beautiful stories that deserve to be celebrated and championed.

What does “reconstructions” mean to you? Both as the title of the show and as a historical or contemporary reference?

Historically we are taught that Reconstruction was the period after the abolition of slavery. Well that is bullshit — it was simply rebranded. It is 2020 and I am still feeling the reverberations of slavery. My maternal family hails from Arkansas and the paternal side from Mississippi. The stories my grandparents would tell me about their youth sound exactly like slavery. I am the legacy of the Great Migration, which happened because of failed “reconstruction.” So naturally, I have a skeptical view of its historical significance. Especially when I have only been fed a white-supremacist history to the point of gluttony. However, when placed in the context of the show, I thought it was a very clever way to frame the work of the selected exhibitors. It gives us the opportunity to address so many of the ills of this country from the Black perspective. MoMA has one of the oldest architecture departments in the entire country, yet has never had an entirely Black architecture exhibition. How is that for reconstruction? In a way we’re taking back the institution and reconstructing it with our own vision. I love that I get the opportunity to reframe the perception of Blackness in this country that was built off our backs, and to reconstruct the opinions of many bigoted individuals.

Can you describe the project you’re creating in response to the MoMA Reconstructions brief? Where is it and why did you choose that location?

My project is titled A Spectrum of Blackness and it looks at Miami — as the exhibition’s youngest participant, it made sense to pick a young city. The goal is to highlight the various sediments of Blackness, utilizing the kitchen and porch as the spaces to excavate these complexities. Many individuals foolishly perceive Blackness as a monolith — I was one of them, even though I’m Black! When I first moved to Miami, I was repeatedly asked, “Where are you from?” I would always reply, “Chicago.” They would always follow with, “But from where?!?” I would get more specific and say “The west side of Chicago.” And I would repeatedly be met with angst and annoyance, not realizing I was really being asked what country my family is from, since in Miami one can be Black but identify as Haitian, Jamaican, Cuban, Dominican, Bahamian, etc. This spectrum encompasses so many legacies that are shared and singular. I’m trying to highlight the variations of language, dance, and spatial occupation. It’s more anthropological in nature than specifically architectural. But that’s what makes my practice unique, since I use architecture as the vehicle to tell these important stories. Hopefully, when you leave my portion of the exhibition you’ll have a better understanding of Miami as a Black city, and the significance of the kitchen, porch, and water to these communities. The other part of my project is joining forces with nine fierce architects to create a collaborative and fill the gaps that architecture doesn’t appear to prioritize. It is a clear act of reconstruction on its own and a real personal step towards crafting our own architectural narrative. My hope is that when the show is de-installed, this will continue to move things forward for Black architects and create more opportunities for us to express ourselves. Not just as Black architects — because that assumes we can only design things related to the Black experience — but so that we can fully realize all the intellectual and radical ideas we’ve had to suppress as a result of white supremacy and racism.

Interview by Drew Zeiba

Video portrait by David Hartt

Editing by Jessica Lin

Music by King Britt presents Moksha Black

A PIN–UP production in partnership with Thom Browne

This video is part of a series of ten portraits David Hartt created for PIN–UP on the occasion of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America at the Museum of Art (Feb 20–May 31, 2021), curated by Mabel O. Wilson and Sean Anderson. The portraits were also published in the print edition of PIN–UP 29.