NOTHING IN MOMA: Abraham Adams’s Exaltation of Absence

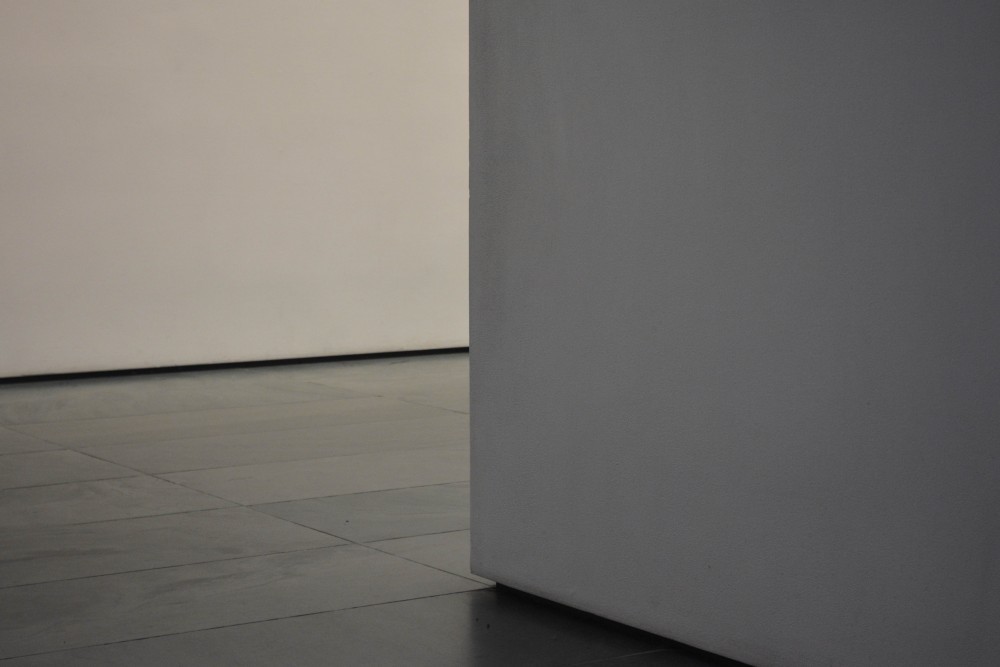

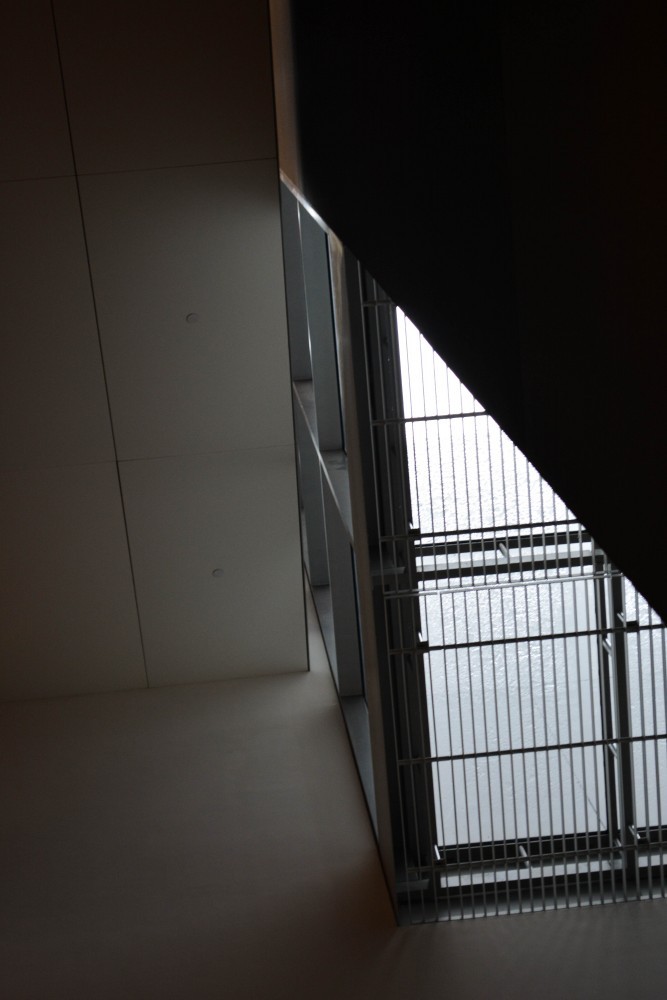

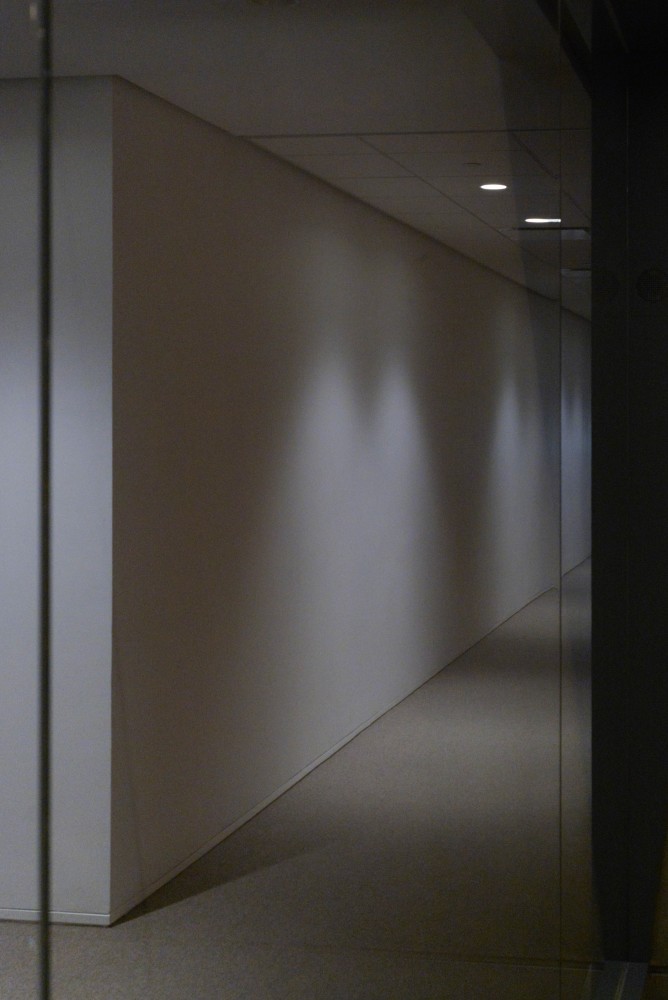

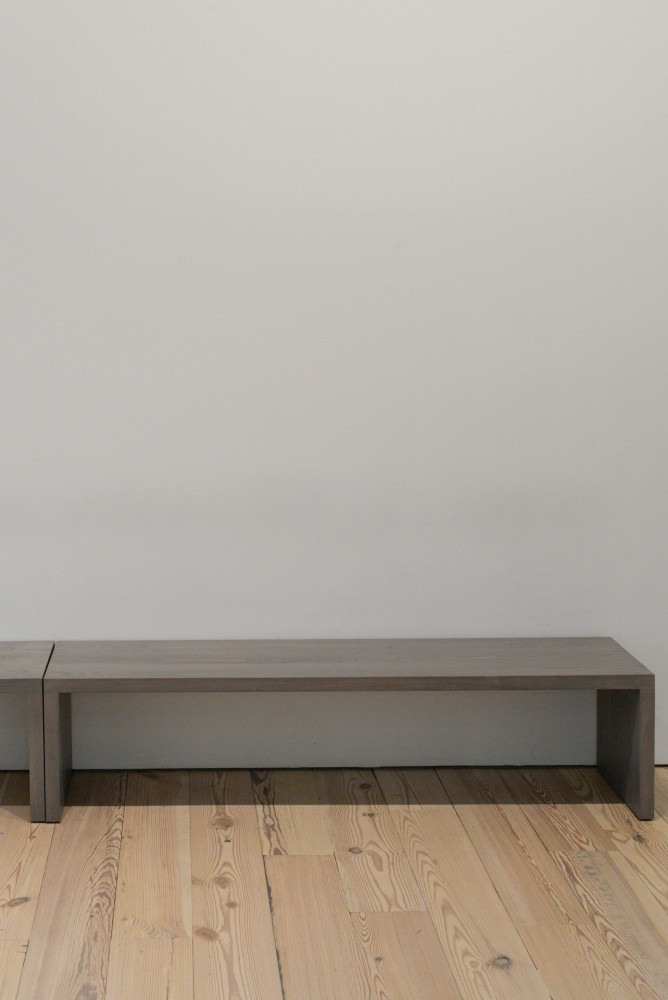

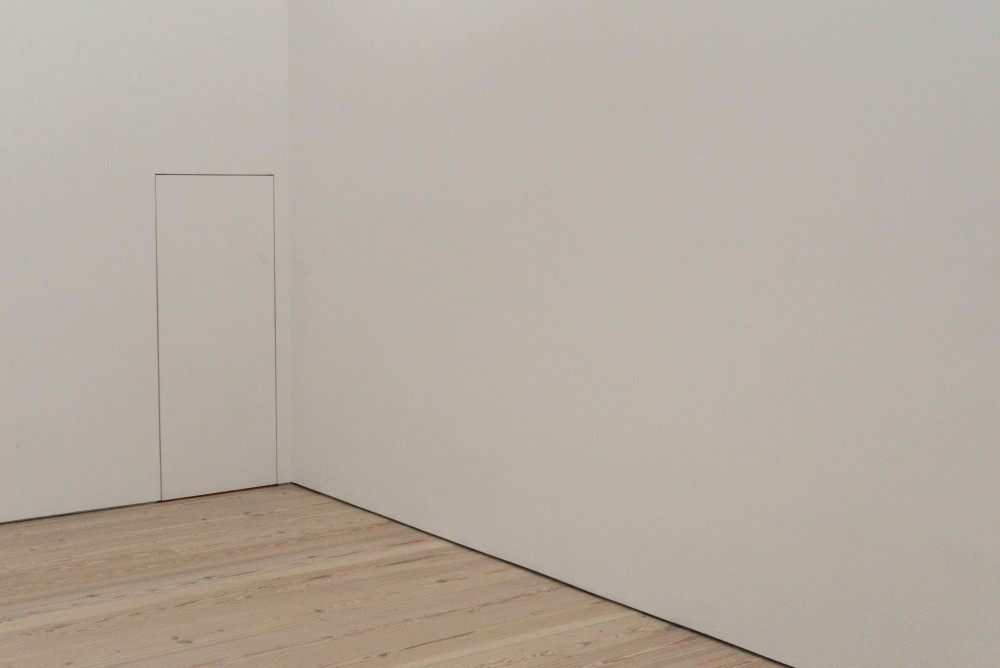

Abraham Adams’s book Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018) is a collection of photographs taken in New York museums where, at a given moment, there happened to be no artwork, wall texts, people. Apart from an introduction by the art historian David Joselit and the usual business of copyrights and colophons, the book contains no text. The photographs in Nothing in MoMA are presented without captions. Their layout is irregular — the photographs on any given page or spread might be printed alone, paired together, stretched across both pages unevenly, their centers disappearing into the shadowy folds of the binding. Unaffected, they exhibit dry reality: three empty seats in front of a tangle of empty coat racks; an ornate railing; a more bland railing; stanchions pulled taut, and slightly off-kilter, by the wires designed to keep people from getting too close; so much white.

One might expect these pictures to appear in a high-gloss coffee table book, something of almost architectural size. Those expectations would not be met. The book is small, thin, like that of a novella or book of poems; it doesn’t encourage a preciousness in its objecthood nor in its viewership. Rather, it suggests that always when seeing or looking we are reading. While there is not a single word in the book from Adams, a poet and critic, not even a dedication, the images still form a text, something that Joselit hints at in his introduction: the “empty, bland nowhere (of the museum) is always there, a grammar that organizes and secures our scene of looking.” If the museum-as-artifact acts upon us using a “grammar,” then this book is a syntactic and semantic re-structuring of the museum’s linguistic codes against its obfuscatory architectural artspeak. To read is to see spaces between letters printed and pages turned. It is nothingness that makes presence coherent and legible, the gaps between things that let us see those things as things at all.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

There is one photograph in particular that always stops me when I flip through the book. Haunting and still, it shows a square cutaway in the white wall of an unlabeled museum. A sleek version of a drop ceiling casts a shadow just along the square’s left edge. Through this would-be window, just darkness. We can’t see anything, it reveals neither outside nor other side. Holes, like mouths, speak, excrete, ejaculate, or at least they could. This one refuses, becoming not only the punctum of the photograph, but of the museum, and its very buildingness, itself.

What an empty buildingness. Despite their mandate of hoarding and accumulation, most modern museums make their presence most pronounced through lack. While luxury once was defined through performative excess — showy overstuffed rooms fit for soon-to-be-headless monarchs and opulent museums hung salon style with paintings reaching to the roof — this materialistic glut is now the déclassé way of the nouveau riche; today’s accepted mode of performing class is to mime modernism and create studied displays of just how much space you can waste. Like Kimye’s IG-ready beige-and-gray homes or high-end boutiques (the OMA-designed Prada store in New York comes to mind) that produce the sense of “luxury” with an abundance of absence, that is, by figuring and disfiguring of surplus, the contemporary museum often attempts to recede into its own background. While museums might at times be architectural marvels — the various international Guggenheims, with all their starchitect cred and dazzling façades that lead to interiors of questionable practicality are prime examples — most museum and gallery spaces choose not to assert themselves through manifest architectural imposition, but instead through their own studied minimality.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

Simply put, most museums are boring. At least inside. Their function of rerouting the gaze, as “engines of attention,” as Joselit puts it, is necessarily as much about focus as about boredom. One prime example would be the Renzo Piano-designed new Whitney on Gansevoort Street, a museum that is depicted in Adams’s book. It’s a rather dull building. Maybe that’s the point. Its bare expanses make it adaptable for displaying art, and for framing views of the Hudson.

Discussing the Whitney and its boringness, architect and historian James Graham writes in The Avery Review: “The paradox of hyper-minimalist detailing is the massive effort of architects, contractors, and tradespeople required to materialize that nothingness, and Piano’s modus operandi has long been a distinctive blend of tectonic over-articulation and concealment. The claim, as always, is that the architecture steps aside for the benefit of what’s on display.” Like the seamless planes of so much Minimalist and Conceptual art that were made by so many individual laborers that see so few dividends, not only the construction workers, but also the cleaners and art handlers and guards, all variety of underpaid contract labor, are disappeared by the museum’s self-conscious recession from itself. How many hands to make a white so white that it seems no hand has touched it at all? How many people attend to these corners that museumgoers are not meant to attend to at all? Adams doesn’t show these workers either, but by displaying the museum so prominently, and that is, displaying its nothingness, he reveals precisely what and that we don’t know. He reveals how little the museum wants to reveal (of) itself.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

-

Abraham Adams, Nothing in MoMA (Punctum, 2018). Photography courtesy the artist.

Andrea Fraser may have been bold enough to fuck the architecturally assertive and insertive museum in her brilliant institutional and feminist critique Little Frank and his Carp, the notorious 2001 video where, clad in a neon chartreuse dress, she rubs herself against the Frank Gehry-designed Guggenheim Bilbao, her disruption turning herself into yet another object to behold against the museum’s now overly visible backdrop. But Adams keeps his distance, all the more creepy, and perhaps all the more erotic. Scopophilia, like Fraiser’s parodic objectophilia, is just another form of sexual substitution; institutional critique, here as capture, is also just institutional embrace: a photo album of a dear friend-turned-frenemy clung onto, all so obsessive. Reproduction only produces so much distance from the so-called original. Joselit’s full quote from above: “That this empty, bland nowhere is always there, a grammar that organizes and secures our scene of looking is in fact obscene, an embarrassment.” The voyeur and the viewed both evoke disgust, never more so than when seeing themselves in the mirror.

However, this ambivalence does not weaken the critique, it only points out our own ambivalent feelings and values as museum-goers. In reproducing the museum, a “picture-engine” as Joselit terms it, in pictures, Adams’s images induce us to see the museum as the bare object it is. Nothing in MoMA rewrites the museum as a text, and by our reading that text we come to see the museum exhibit itself. These buildings are just that: they are material and produced by material conditions — by human labor and by economic contingencies — that have been subjected to a white-walled aesthetic erasure, a blank-pagification, which, like an ouroboros, creates and sustains the context for and ideology of capital-A “Art” as we know it. “Adams takes these vanishing points, and makes them into pictures,” Joselit says of the photos’ rendering the museum’s nowhere zones. Sometimes a hole promises somewhere else to go. Sometimes a hole is just a hole.

Text by Drew Zeiba.

Photography courtesy Abraham Adams.