SEEING AND BEING SEEN: A Cinematic Diptyque Explores living online

There is a severe polyvocality to being online, a multithreaded logic that pervades our very psyches. Filmmakers Micaela Durand and Daniel Chew capture this logic in First and Negative Two, two short films they co-directed and which are loosely-linked.

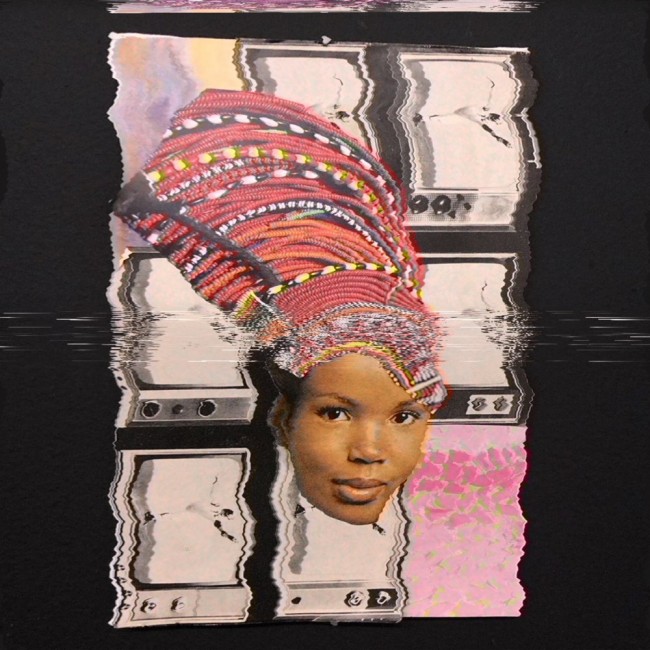

Both First and Negative Two explore this cacophonous contemporary condition by layering text, voice, and image. First follows a young girl through an average day in New York — out in the city itself as much as in her bedroom, in ride shares, and online. Durand and Chew describe it as a character study, but it perhaps best explores the camera as character. Some shots bounce and fall as if captured by an iPhone swinging in someone’s hand; others stalk like an Instagram story made behind someone’s back. (At one point, our protagonist follows through the streets a woman she finds fascinating, her camera consuming the stranger’s aesthetic like an IRL moodboard.) Subtitles appear, rendering not dialogue, but what we can assume are incoming or outgoing text messages. They act as anti-captions of a sort: the relationship of the text to the onscreen imagery, even conversations being had, are circumstantial. While there of course is the human protagonist living her life and making herself-as-image, the film, in its imagistic immateriality, lives the life of the camera phone.

-

Still from First by Micaela Durand and Daniel Chew. Image courtesy of the artists.

-

Still from First by Micaela Durand and Daniel Chew. Image courtesy of the artists.

-

Still from First by Micaela Durand and Daniel Chew. Image courtesy of the artists.

In Negative Two, Durand and Chew continue their investigation of polyphonic, mediated online life. The camera follows Devin, a young gay architect who spends his days staring at screens at home and at work, talking on dating apps, chatting about birth charts. The usual. Unlike First, the filmmakers do away with subtitles, relying instead on voiceovers to relay Internet conversations.

If the camera was a character in First, in Negative Two the city of New York joins the cast as well, its urban landscape playing an active role. In the film, Devin chats with Grindr guys about architecture: “Do you have a favorite building?” “Ford, Sunnyside Gardens, Grand Central is great.” “That forest lobby is cool.” “You should go, it’s better in person.” “I can just walk in?” “Yeah, it’s supposed to be public.” “What does that mean?”

What does that mean? The phenomenon of private-public spaces is a perverse regulatory regime of the neoliberalized city whereby corporations own our so-called “public spaces,” courtyards and parks and indoor seating areas that municipalities mandate companies to make room for when building new buildings. It’s a physical parallel to the way in which private companies — like Instagram or Grindr — own the data we choose to publish about our most private selves. In both Durand and Chew’s films the bedroom is as much the landscape of public life as the city, and as the screen.

In the same way that we expose ourselves online, much of New York City’s architecture of the last several decades exposes too; there’s a lot of glass. In Negative Two, the Ford Foundation with its visible beams, is distinguished by its large central atrium garden, an oasis in the gray stretches of midtown. It may be his favorite, but Devin’s visit to the Roche-Dinkeloo-designed building is uncomfortable. Its forested center serves less as an oasis than an abyss. The camera is held at a distance, a sneaking voyeur, moving behind trees to capture a glimpse, looking away and spiraling up vertiginously. One almost expects a homicide about to happen. In another glass building, Devin finds himself in the dimly lit apartment of an older man. “Your view is so nice,” he says, looking out the large windows. He pauses. “It feels like we’re so high up. We’re designing a building at work right now that’s — I think — a little higher than this.” Awkward chit chat follows. “Take your inspiration,” the mature hookup says as Devin admires the nighttime cityscape. Some tequila gets poured. The man kisses Devin’s chest, possibly more — it’s ambiguous from the camera’s vantage point, outside looking in through a window frosted with condensation. In the midst of their presumed sexual encounter the camera wanders, training itself on an adjacent, anonymous building, its glass façade reveals no interior, just the mercurial, flowing reflection of lights from cars down below.

Reflections abound in the film. Lights flow as Devin and the camera stare up on the gleaming escalator of Herzog & De Meuron’s Public hotel. Passersby on the street take selfies in the shimmering façades of new construction. Reflections reveal the surfaceness of things, with shiny surfaces acting as mediators between us and the way we see ourselves, producing always in their mirrored seeming-sameness a distance and difference. A similarly shiny building also served served as a backdrop for the films’ New York premiere at The Shed, the new arts center that is part of the recent Hudson Yards development. More and more we experience buildings as images — whether that’s Devin staring at 3D renderings at work or the shiny towers that backdrop the sexy selfies on our feeds — the glass buildings themselves becoming like the screens we access them through.

Negative Two opens with what might seem a non-sequitur: guys, all guys, working out at a gym while loud industrial music plays. Bodybuilding, a nice pun for a film about an architect. But these gym bodies are also are designed to look hot in photos — maybe photos sent to Devin on Grindr. Existence has become just another form of looking. We’re voyeurs of our own lives.

The camera in both of Durand and Chew’s films is evocative of yet another form of seeing and being seen: the reality of constant surveillance. It’s a manifold phenomenon: state surveillance, certainly, but also the self surveillance of living in a world that demands constant documentation. Also, the surveillance of others. The city becomes a place of witnessing and avoiding witness, of becoming witness, refusing. The stalking is sometimes half-hearted: the camera floats away and wanders the streets of Chinatown by itself to reconnect with Devin further along. Even handheld, our cameras have lives of their own.

Watching and thinking through both First and Negative Two, neither run more than half an hour, one could be led to believe all life has just become Rear Window with a software update — our windows, that is, our frames of seeing and surveillance at once mobile and fixed. Our eyes and cameras move, but the movement is maybe a false sort of independence. We’re never alone if we don’t want to be, even when we’re by ourselves. We’re one alert away from a dopamine hit, one Grindr location shared away from a blowjob. Or we’re sending nudes, heads chopped off, from the safety of our own homes, now just a platform. We’re always too seen and not seen enough. Someday the only thing of us left will be pictures.

Text by Drew Zeiba.

Images courtesy of the artists.