RECONSTRUCTIONS PORTRAIT: Mario Gooden on the choreography of Black Spatial Praxes

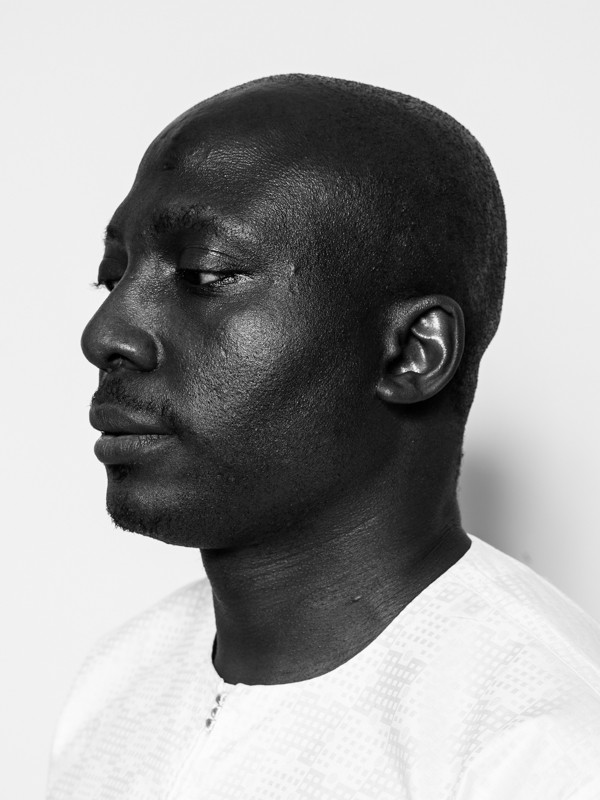

𝘖𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘔𝘶𝘴𝘦𝘶𝘮 𝘰𝘧 𝘔𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘯 𝘈𝘳𝘵, 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵 𝘋𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘥 𝘏𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘰 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘸’𝘴 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘳𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘪𝘦𝘸𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘵 (𝘴𝘦𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘰𝘸). 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗’𝘴 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘚𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘈 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘩𝘪𝘱 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘮 𝘉𝘳𝘰𝘸𝘯𝘦.

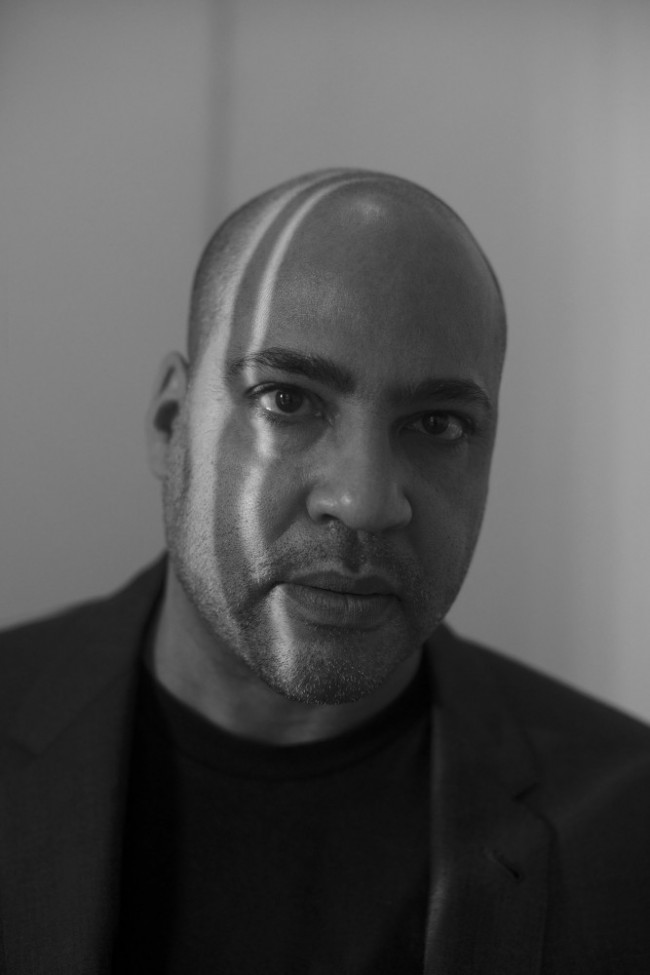

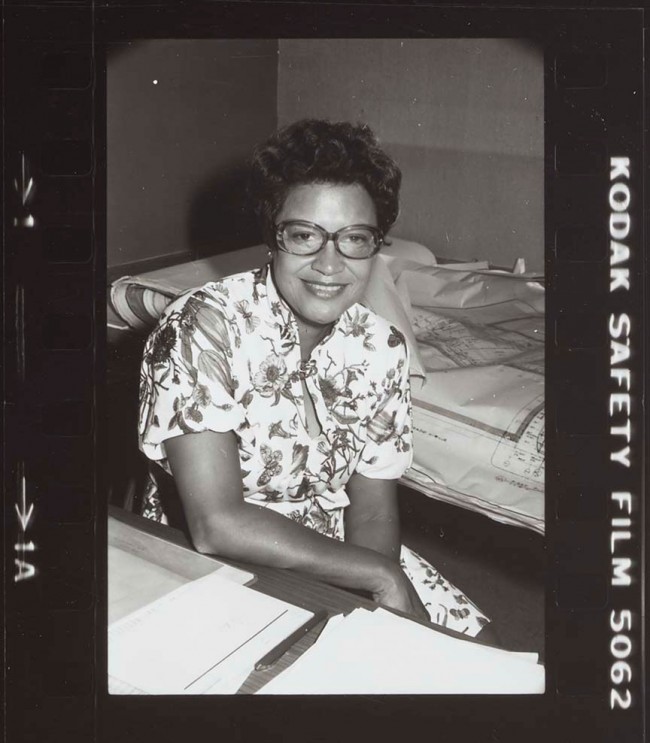

Architect, artist, and researcher Mario Gooden’s practice ranges from physical buildings to solo and collaborative multimedia performances. Founder and principal of Huff + Gooden Architects, as well as Associate Professor and Co-Director at the Global Africa Lab at Columbia GSAPP, Gooden examines and complicates the interstices of race, gender, sexuality, and technology as they play out in the built environment.

Mario Gooden photographed by David Hartt for PIN–UP.

PIN–UP: What led you to architecture?

Mario Gooden: From a very young age I was always interested in the liberatory potential of space, subjectivity, and identity. I first became enthralled with architecture around age ten or eleven, and in particular with Le Corbusier’s Œuvre Complète and the Five Architects book. Although the architecture and the spaces were not designed for me — just the opposite, they were spaces of exclusion — I nonetheless projected myself in those spaces and felt I had a right to occupy that space. I was much more interested in the space-making, event-space, and performative conditions of occupying Modernist space than the image qualities or form-as-object conditions of these buildings.

How has your practice evolved?

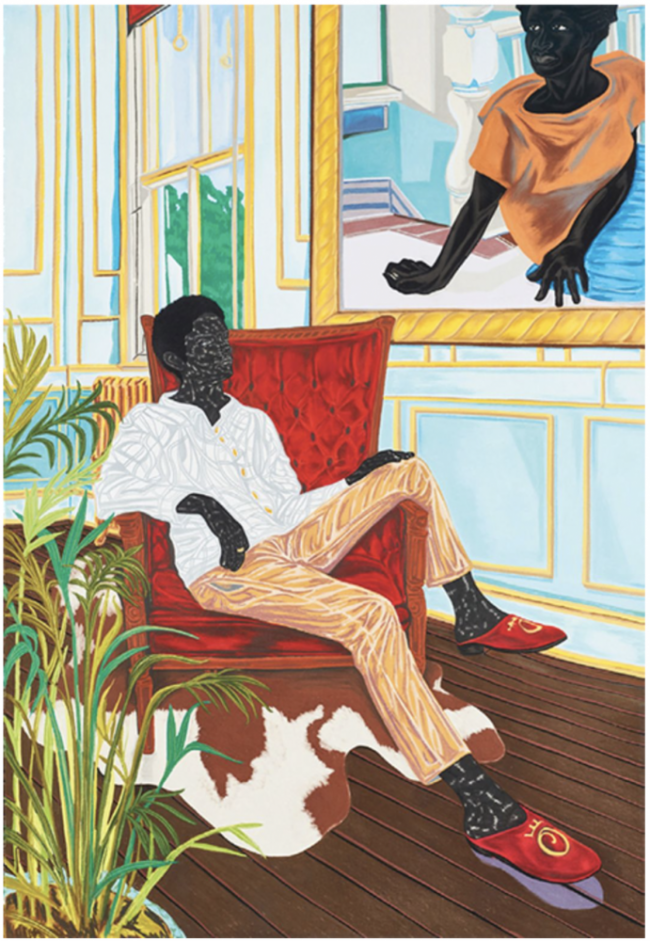

My practice is interdisciplinary and my studio approaches architecture as a mode of culture and knowledge production very much in alliance with artistic, literary, and performative modes of production. The practice has evolved to become multi-disciplinary in terms of thinking of architecture within these other disciplines and not separate or apart from them. I see my work as a cultural practice engaging the intersectionality of architecture, race, gender, sexuality, and technology by crossing the thresholds between architecture and the built environment and writing, research, and performance. In particular, the consideration of performance and multimedia in my work opens up a mode of architectural representation that is much more specific with regards to subjectivity and identity in architecture. My collaborations with the choreographer Jonathan González and the performance collective Dark Adaptive (artist Torkwase Dyson, movement artist Zachary Fabri, and artist and designer Andres L. Hernandez) have been intended to further explore liberatory spatial practices within architecture. For Black people, liberation has always been a spatial practice.

What does “reconstructions” mean to you? Both as the title of the show and as a historical reference?

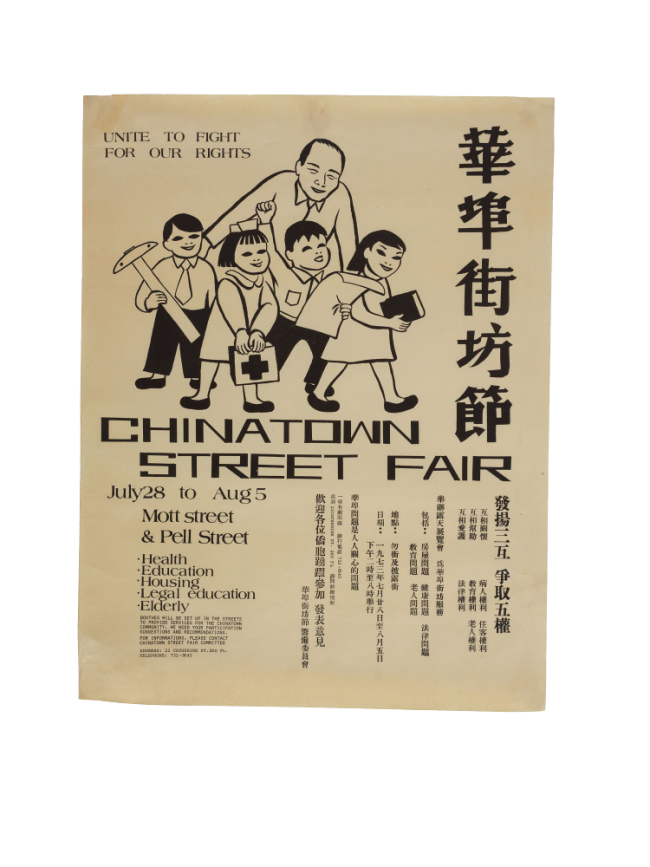

WEB Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America revised the historiography of the Reconstruction era and illuminated Black agency not only towards our own liberation but also towards reconstructing the ideals of American democracy. Since emancipation, Black people in America have continuously pushed the U.S. towards that becoming. First, America was built by the free labor of enslaved Africans who are just as much founding fathers and mothers of America as the signatories of the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Then, Reconstruction showed the possibilities of what America could become. But it would take the civil rights movements to further unmoor the conscience of the nation and to pierce its soul while at the same time Black culture and Black cultural production were becoming the soul of the nation. There is a clip in Arthur Jafa’s *(Love is the Message, the Message is Death )(https://www.moca.org/exhibition/arthur-jafa-love-is-the-message-the-message-is-death)of the actress and activist Amandla Stenberg asking “What would America be like if we loved Black people as much as we love Black culture?” And I believe that we see now that Black people and Black culture-makers and thinkers are at the forefront of a coalition of people of color, women, and the LGBT community working for justice and bringing about a social and cultural revolution. *Design creativity and space-making have been key at each moment of this continuous reconstruction. From the period of chattel slavery, Blacks have creatively appropriated various aspects of the built environment and landscape to invent new uses, programs, and forms of visibility. Out of necessity and due to the fugitive conditions of Black life, these modalities have always been and remain agile, transformable, and fluid — suggestive of the ways in which Black people have moved through space, negotiated the barriers of social, political, and economic landscapes, and reformulated spatial conditions through these very migrations and displacements, improvising new ways of being. Furthermore, out of these conditions emerged painting, sculpture, dance, and music unlike anything anyone had ever seen before. Yet, in some ways, the formal conditions of architecture have been the most resistant to respond to the Black imaginary and agility.

Can you describe the project you are creating in response to the MoMA Reconstructions brief? Where is it and why did you choose that location?

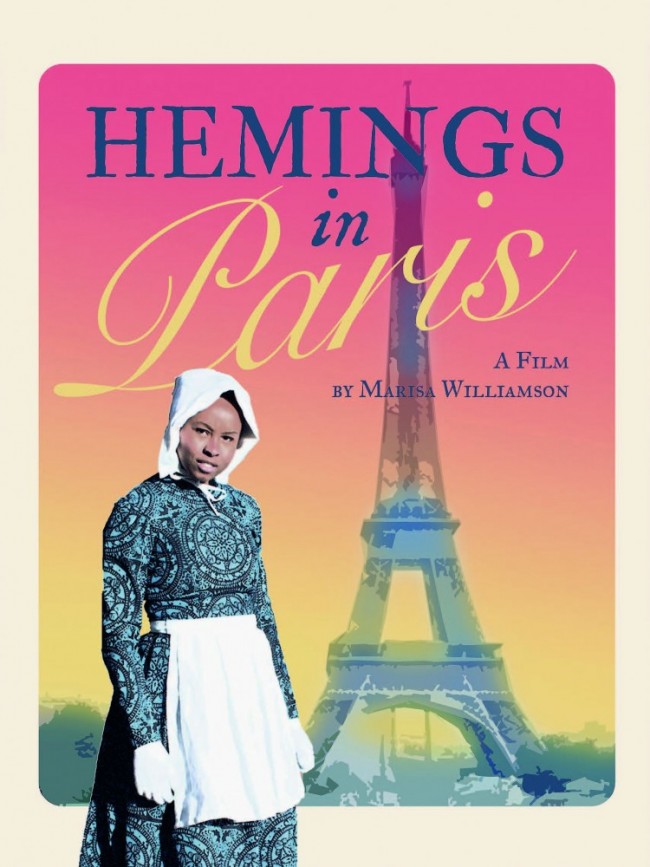

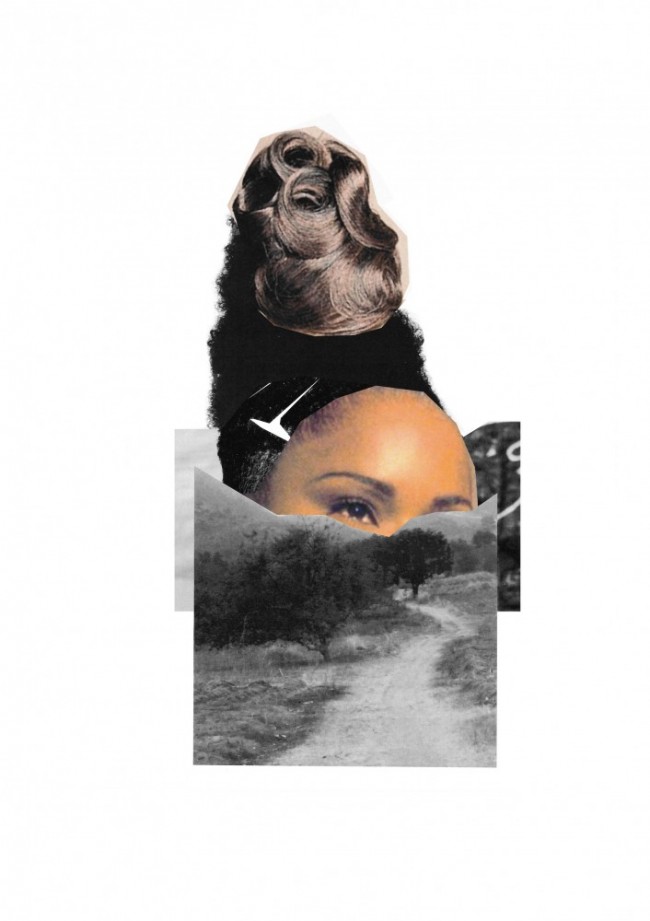

My project explores the choreography of Black spatial praxes and modalities in Nashville, Tennessee, including the formation of the first Black-owned independent streetcar line in 1905 and some of the first civil rights sit-ins, marches, and protests of the 1960s, which foreshadowed the Black Lives Matters protests, marches, and die-ins from 2015 to the present. Entitled, The Refusal of Space, the project is a “protest machine” and multimedia mobile architecture incorporating sound, video, and projected photography to recall and enact the spatial action of protests, marches, and sit-ins in downtown Nashville. The three significant sites of the civil rights movement have recently become part of Historic Nashville’s Civil Rights Tour. Enacting feminist theorist Tina Campt’s concept of “practicing refusal,” the project uses juxtaposition and collage to resist conventional forms of architectural representation as a counter to the historic exclusion of the Black body and manifestations of Blackness in architecture.

Interview by Drew Zeiba

Video portrait by David Hartt

Editing by Jessica Lin

Music by King Britt presents Moksha Black

A PIN–UP production in partnership with Thom Browne

This video is part of a series of ten portraits David Hartt created for PIN–UP on the occasion of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America at the Museum of Art (Feb 20–May 31, 2021), curated by Mabel O. Wilson and Sean Anderson. The portraits were also published in the print edition of PIN–UP 29.