INTERVIEW: Joy Matashi On Black Hair As Architectural Medium

In post-independence Nigeria of the 1960s, buildings were radically transformed thanks to new Modernist approaches to African architecture. At the same time, fashion, art, design, and personal style also experienced their own shifts. Iconic architecture has long inspired other aesthetic fields, and in Nigeria hairstyles and gelés (head ties) drew explicit inspiration from the built environment around them, including from new structures like the Cocoa House in Ibadan, Nigeria’s first skyscraper and the National Theatre in Lagos which opened a decade later in the 1970s. Trained as an architect, artist Joy Matashi brings this West African Modernist heritage into the 21st century by exploring the architecture and geometry of hairstyles in her cross-disciplinary practice. She describes her hair designs as a form of “small architecture,” where the head serves as a foundation for her creations. Based between London and Abuja, Nigeria, Matashi realized the potential of using black hair in her work. She spoke to PIN–UP about the versatility and politics of experimenting with black hair as an artistic and architectural medium.

Jareh Das: Can you describe how you came to use hair as a medium for bringing together ideas of weaving (braiding), architecture and design?

Joy Matashi: The architecture school I studied in allowed for experimentation with nontraditional materials to create nontraditional forms of architecture. Anyone who knows the AA knows the school isn’t concerned about “building buildings,” but developing experimental concepts. School was a laboratorial mess, and hair felt like a natural medium to experiment with — following a bad hair experience at the age of 12 — I vowed to

Black hair is political, personal, and cultural. Do you see your work as furthering the conversation beyond identity politics by reframing “hair as architecture?”

It’s an unavoidable conversation; black hair will always be political, personal, and cultural however I play with it. An afro will always be a symbol of resistance and a celebration of black beauty. One of the first notable waves of resistance to eurocentric standards of beauty, the Black is Beautiful movement, was a celebration of Afrocentrism in the 70s and we recently saw the second wave online, with the natural hair community coming together through blogs YouTube and other online platforms. Now you can see black women cutting their hair, getting a fresh start on hair that’s been damaged by chemical treatments, in real life and online through computer and phone screens. Black hair is my subject matter and there’s no way that it can be separated from identity politics. I posit “

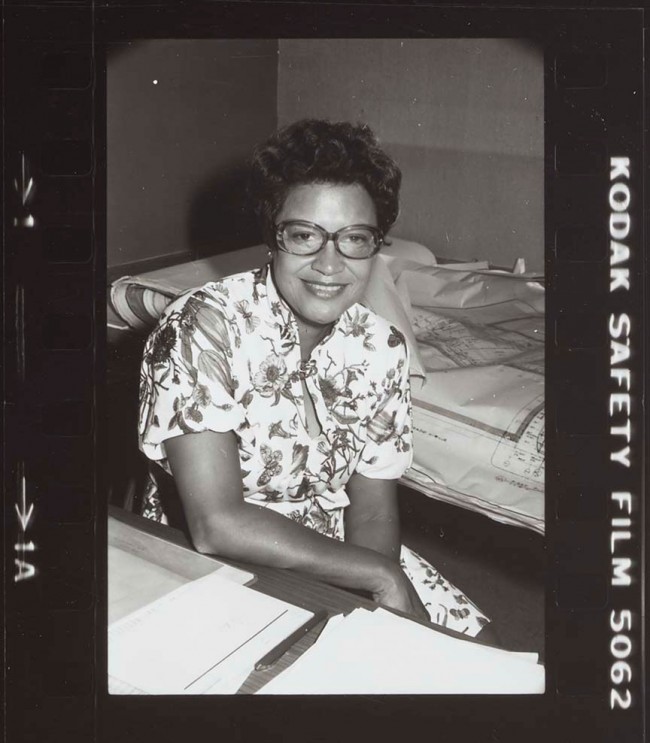

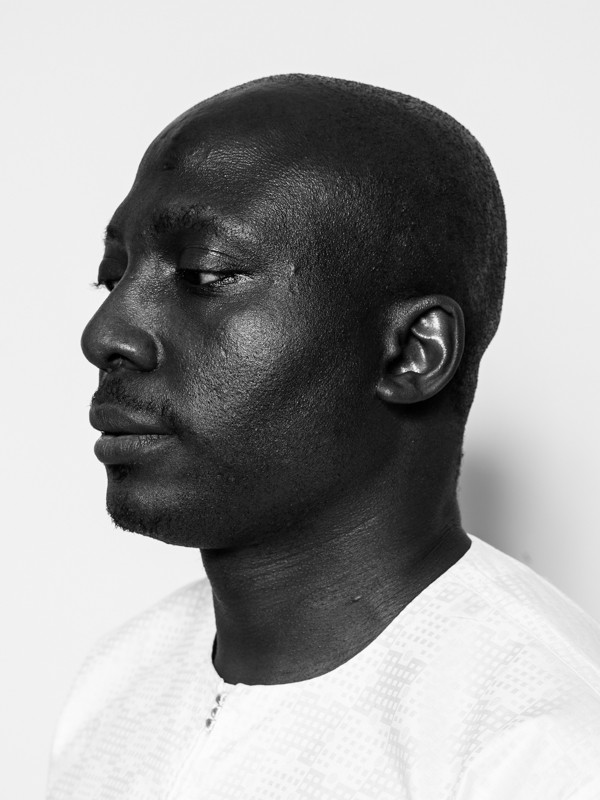

Portrait of the artist Joy Matashi. Photography by Damilola Quadri.

You described in an interview for

Rem Koolhaas’s and Bruce Mau’s book S,M,L,XL introduced me to the idea of playing with architectural scales. I began playing with the idea by scanning braids of hair 1:1 and superimposing them on a 1:50 street plan. Now 50 times its size, I began to imagine this braided object weaving its way through the city. Once you play with an object’s scale, its function changes. Recently, I discovered that there were gelés tied to imitate the National Theatre. It’s interesting how the city’s vernacular scale can influence dress, in this instance headdress.

The Nigerian photographer JD Okhai Ojeikere once said: “Hairstyles are an art form.” Does this statement resonate with you and has Ojeikere’s work influenced your own?

Ojeikere was one of the first artists to document black hair by solely focusing on its form, with the wearer as the support, almost as if they were a plinth. This focused the viewer’s attention on the aesthetics of hair, reframing the hairstyles as sculptural. I lay emphasis on the aesthetics of hair by dissecting popular Nigerian hairstyles and presenting them as small forms of architecture. I see parallels in a conscious act of removing hair from its everyday function to reframe it differently. With Ojeikere it was through the lens of photography, with me it’s through the lens of architecture.

How does living across two geographies and urban environments — London and Abuja — influence your work?

In Abuja it’s so refreshing to not be a minority, to see people who look like you. Wuse Market’s braiding area became a great place for research. I could connect with the braiders. Watching the arguments, listening in conversations whilst hairstyles being done in that space definitely shaped how I view my hair today. You don’t really get the same experience in London.

-

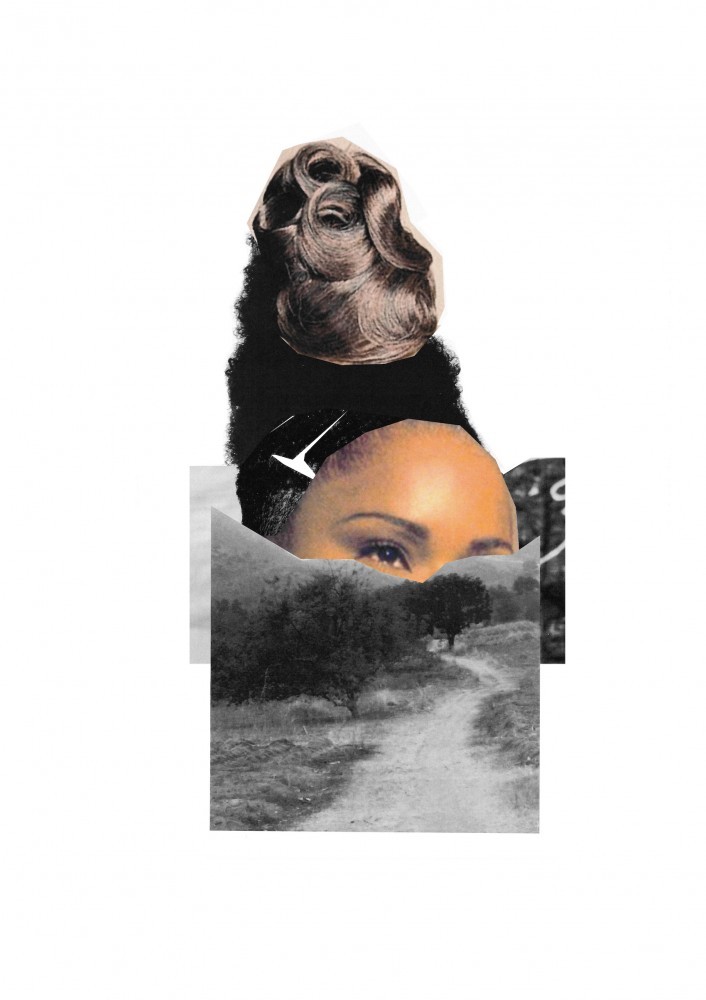

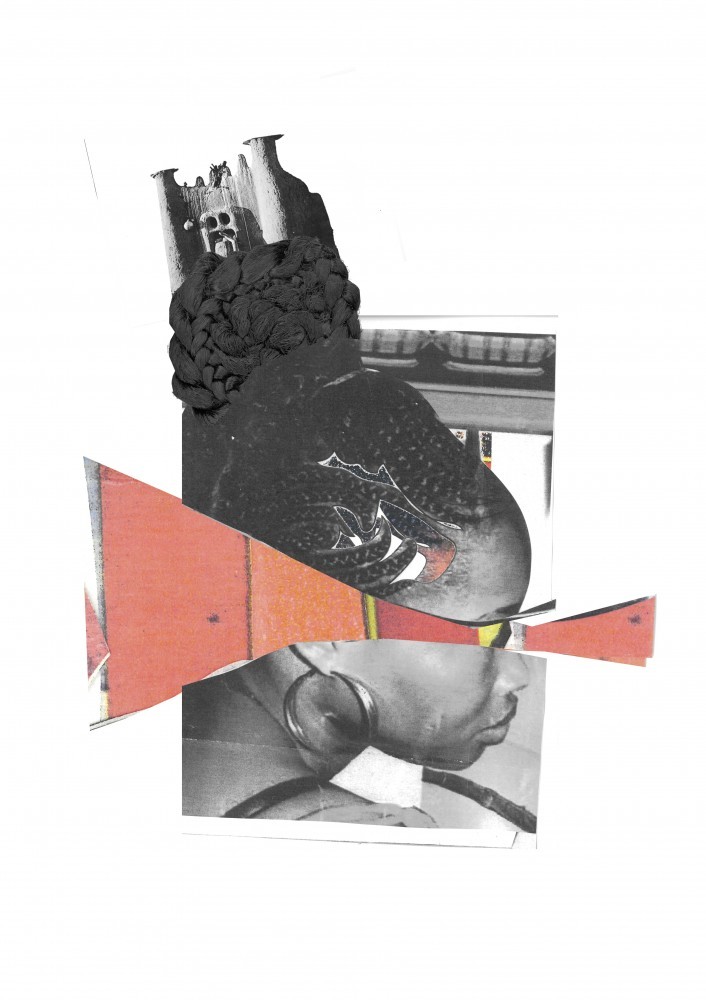

Hair collage by Joy Matashi. Courtesy of the artist.

-

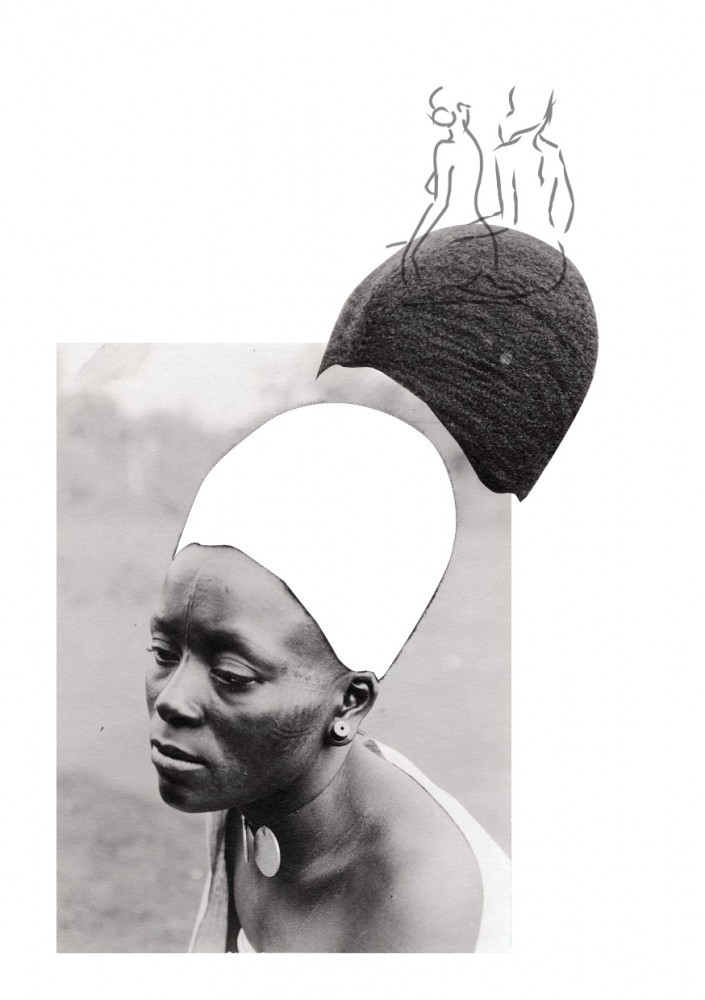

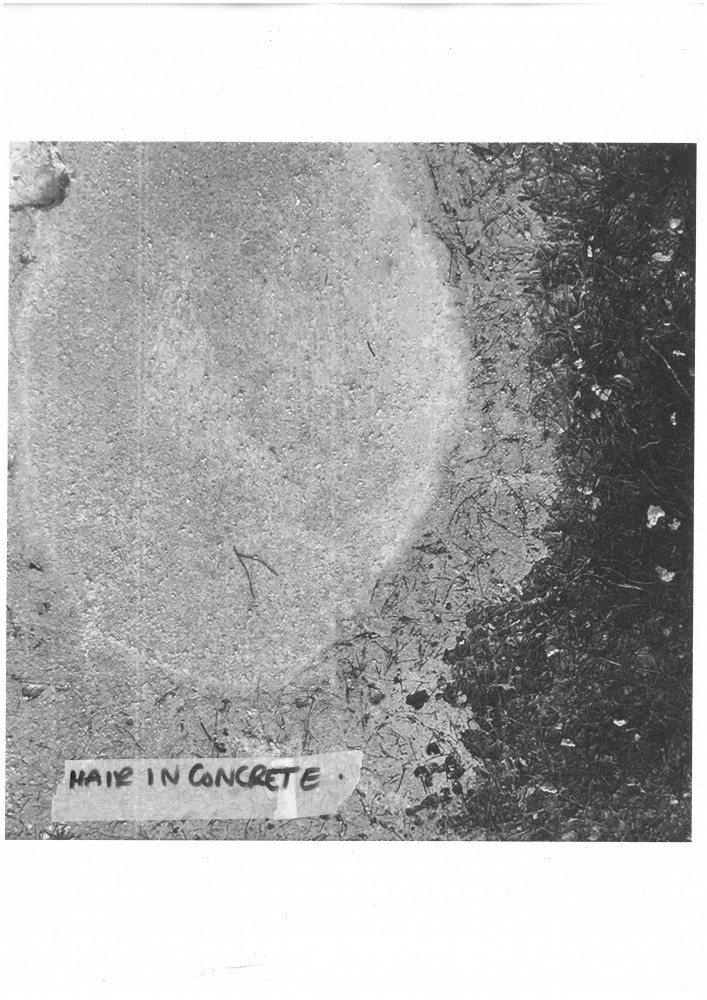

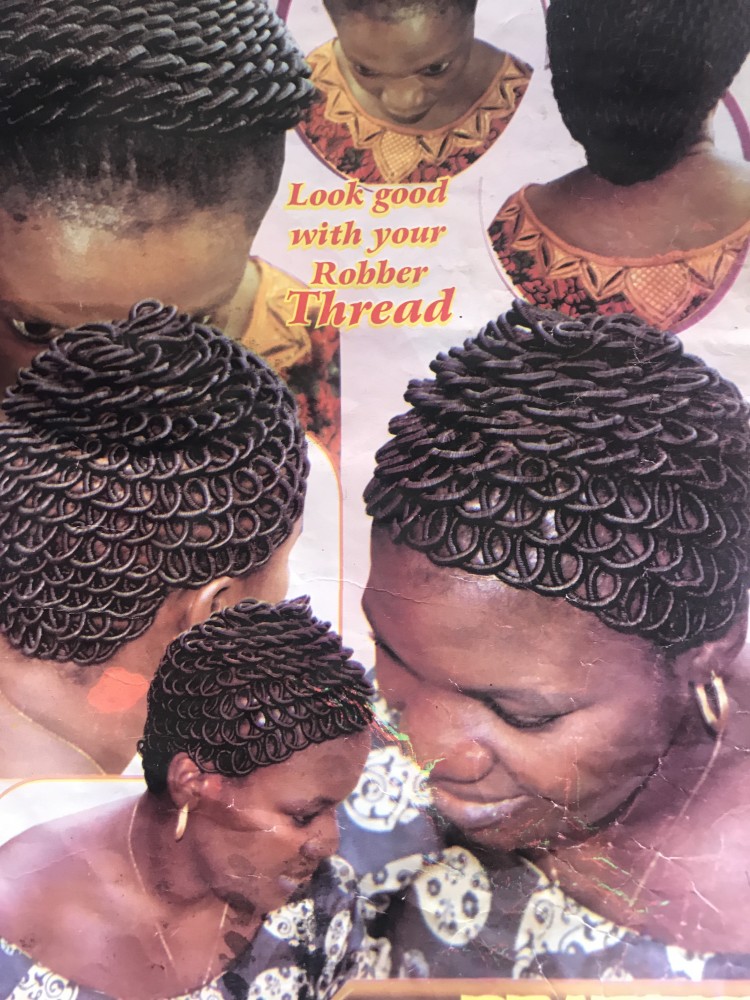

Excerpt from Maman's Braid Catalog. Courtesy Joy Matashi

-

Hair collage by Joy Matashi. Courtesy of the artist.

-

Collage by Joy Matashi. Courtesy of the artist.

What would a hair salon you design look like?

bell hooks stated in “Straightening Our Hair” (an essay in Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black, 1988) that the beauty parlor was a space of consciousness-raising, a space where black women shared life stories — hardship, trials, gossip; a place where one could be comforted and one’s spirit renewed. It was for some women a place of rest where one did not need to meet the demands of children or men. It was the one hour some folk would spend “off their feet,” a soothing, restful time of meditation and silence.” Growing up, the hair salon was activated in spaces I already lived in from the living room, in front of my bathroom sink to on my mother’s lap. To translate being in the comfort of your home to a salon space, would be interesting, but I’d question whether we have it already. The salon space is so portable now, all you technically need is a tool and a chair. In Wuse Market, you would never know a salon existed, ten minutes to closing time chairs are stacked and locked by the side, leaving space in the middle. The next day the chairs are arranged, and work begins for the braiders. I wouldn’t design a salon, but a chair. A chair that could hold the tools and assist the work of a braider, without the client interfering. While the chair’s in use the salon space is in operation, once the hair styling is finished the chair is folded away into a cupboard or a sophisticated bag — the salon is closed, and the room returns to its original function.

Text by Jareh Das.

Jareh Das is a London-based curator, writer, and researcher. She holds a Ph.D. in Curating Art and Science from Royal Holloway, University of London for her thesis Bearing Witness: On Pain in Performance (2018).

Images courtesy Joy Matashi.