INTERVIEW: Agustín Hernández’s Futuristic Monoliths Inspired By Mesoamerican Architecture

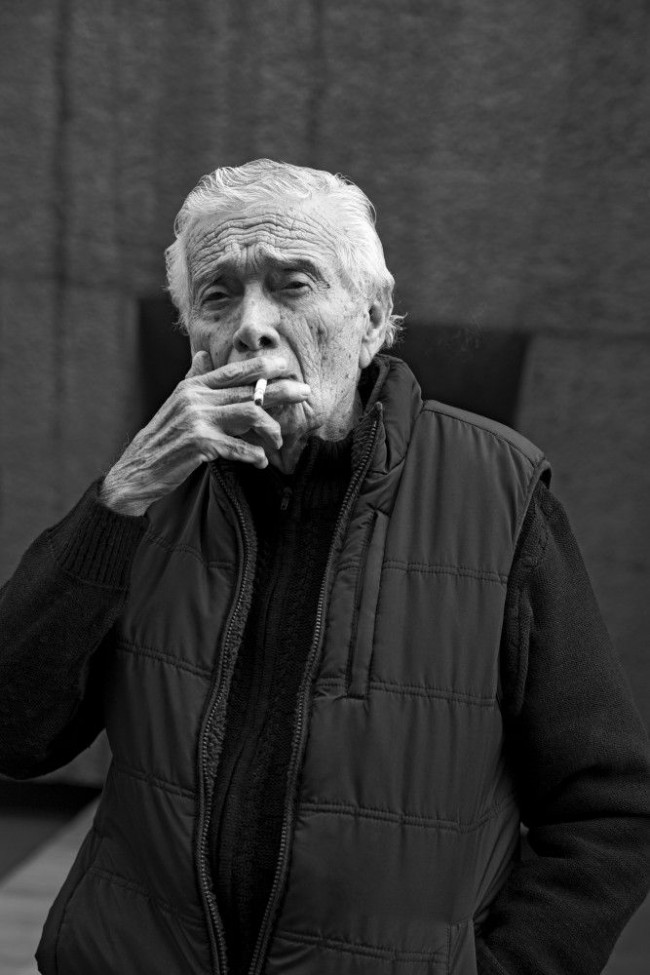

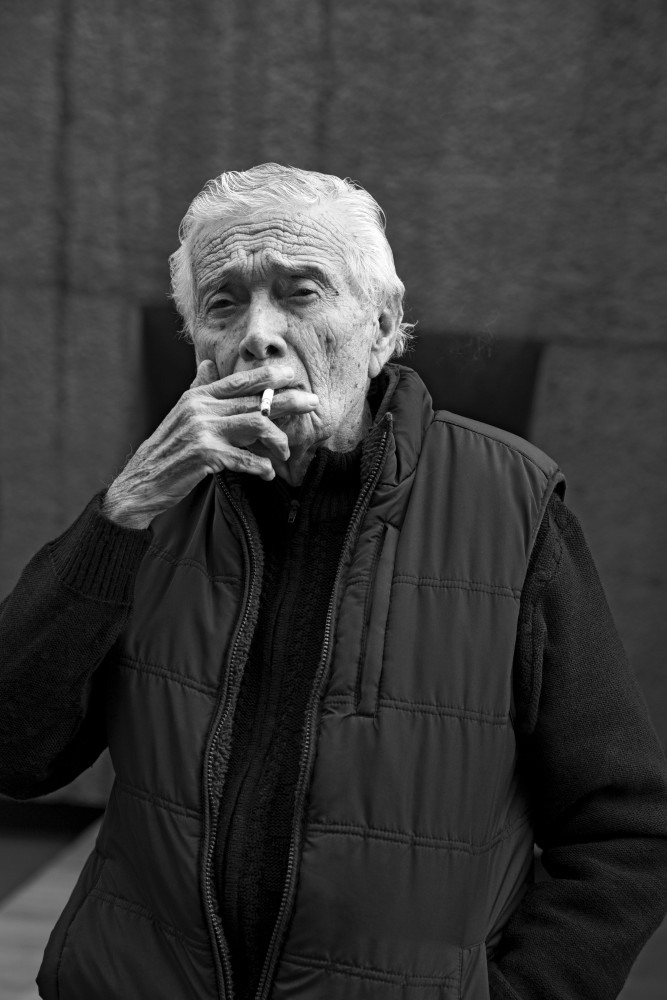

Agustín Hernández photographed by Dorian Ulises López Macías for PIN–UP.

Agustín Hernández is one of the last living masters of 20th-century Modernism — although his is a Modernism with a gloriously idiosyncratic twist. The Mexican architect, born in 1924, boasts an impressive built oeuvre that serves as a link between grand mid-century urban-planning visions and the formally adventurous high-tech fantasies rising in cities around the globe today. His Heroico Colegio Militar (military academy), completed in 1976 in Mexico City (with Manuel González Rul), is perhaps his most important built project, melding indigenous Mexican tectonics and Modernist rationalism to stunning effect. Its rigor and expressive force is said to have inspired Ridley Scott for Blade Runner, and Paul Verhoeven filmed parts of Total Recall there.

But while some of his buildings seem lifted straight from science fiction, Hernández’s greater body of work is defined by its diversity and contradictions. There’s a lightness to his architecture, with volumes that appear to soar or float, but it’s decidedly monumental; sharp, geometric forms abound, but look closely and you’ll find as many sensual, warm shapes; there’s a freedom in his defiance of gravity, but meticulously controlled design and engineering are needed to achieve it. Despite his future-forward vision, Hernández’s work isn’t universally loved in Mexico — neither by fellow architects nor the common folk. Take the Calakmul Building (1997): cited by Hernández as his personal favorite, residents of Mexico City have cheekily nicknamed it “la lavadora” for its resemblance to a washing machine. Hernández — who works as a poet and sculptor as well as an architect — usually gives interviews at the Taller, the much-photographed cantilevered studio he built for himself in Mexico City's Bosques de las Lomas neighbourhood in 1975, but a torrential summer downpour compelled him to make an exception and invite PIN–UP to the house he shares with Trudy Kaegi, his wife of 65 years. It is the day before his 95th birthday, or, as he likes to say, having been born on February 29, his 23rd.

Suleman Anaya: You’re turning 95 tomorrow, and you still design and teach and are as vibrant and curious as someone half your age.

How do you do it?

Agustín Hernández: I think it’s genetic.

My father and mother lived to be 93 and

88, respectively. And honestly, I think smoking is what’s kept me here. I smoke like a chimney.

One of the remarkable qualities in your work is the many oppositions it encompasses.

Dualities are part of life, and I would hope that is reflected in my work. I’ve used many forms, but when it comes down to it, geometry is my religion. I’ve used every existing geometric form — circles, triangles, squares, rectangles.

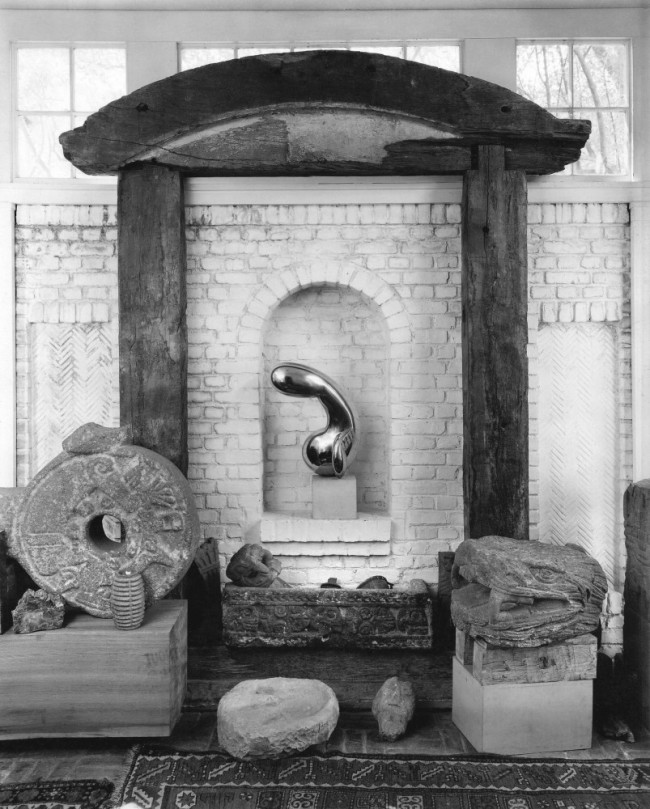

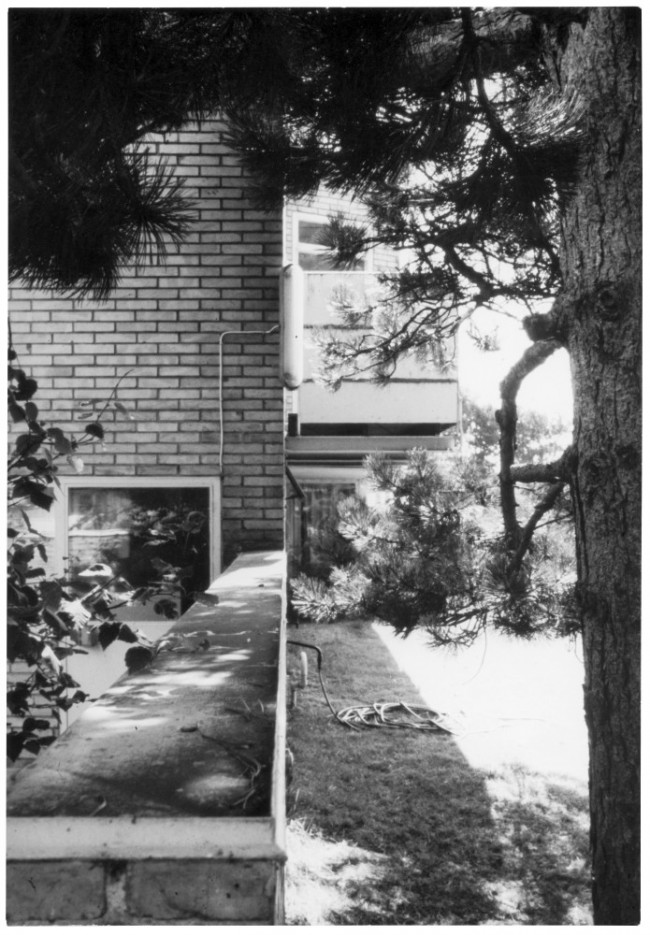

Casa Álvarez, 1971-76. Image courtesy Archivo de Arquitectos Mexicanos (AAM). Fondo Agustín Hernández Navarro. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.

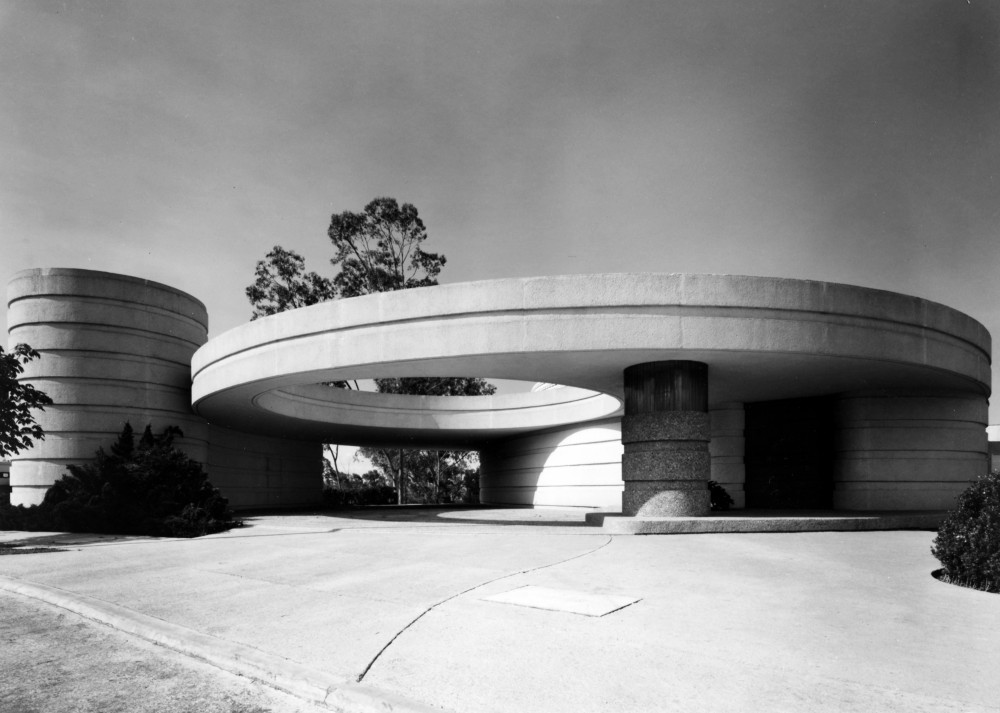

Didn’t you design a house based completely on circles?

You mean the Casa Álvarez? (Mexico City, 1971–76.) It’s a grid made up entirely

of circles, in which curved walls run through the exact midpoint of each circle. It wasn’t easy to build, but necessary for what I had in mind. I like it when a precise logic underlies the architecture, rather than shapes that respond merely to a whim, form for form’s sake. In my work, everything follows a clear trajectory based on geometry. That foundation gives me the liberty to create any shape or space I want.

Where do your designs come from?

They can come from anywhere. For that house, for instance, I had seen a picture

of a fetus — an X-ray — that had really

captivated me, so I knew I had to use it for

a project. I wanted to produce some

thing that responded to that powerful

form I couldn’t stop thinking about.

A building composed from nothing but curves. Other times the references are more obviously architectural. My sister (the dancer and choreographer Amalia Hernández) wanted a convent-like house (Casa Amalia Hernández, Mexico City, 1968–70), with reclusive, compartmentalized rooms, so we toured a bunch of convents. That’s how I arrived at details like ocular openings, which were my interpretation

of 16th-century windows.

At what point and why did you turn away

from your lesser-known early work, which was more conventionally Modernist?

I’ve always sought to make something that’s new. I never repeat myself in my work.

I have always been driven by the desire

to find unknown forms, solutions that didn’t exist before. That’s why I don’t have

a style. Having a style is easy. For me that’s the lazy way out. I am proud I can

say each work of mine has its own

vocabulary. There’s nothing worse than falling into repetition of one mode.

What’s the fun in that?

Still, people have tried to pin you down.

Your work has been called futurist, organic, neo-Aztec — some even refer to it as Brutalist. But it seems to transcend all these categories.

I’m glad you see it that way. I have undeniably been very inspired by pre-Hispanic forms — not just architecturally speaking, even the urbanism of ancient Mexico

is a source of wonderment to me. The

Colegio Militar is based on the concept

of pre-Columbian ceremonial centers.

-

Heroico Colegio Militar, 1976. Image courtesy Archivo de Arquitectos Mexicanos (AAM). Fondo Agustín Hernández Navarro. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.

-

Aerial view of Heroico Colegio Militar, 1976. Image courtesy Archivo de Arquitectos Mexicanos (AAM). Fondo Agustín Hernández Navarro. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.

You once said that a building’s monumentality has little to do with its size.

Yes. Just look at the Olmecs. They could make a sculpture this size (gestures a small height), and you wouldn’t question that

it’s a monument. That’s what I mean — how

a little Olmec figurine can have such

extraordinary force. It’s monumental, but

it doesn’t come from scale.

How do you produce that expressive quality without going big? Your building for

the Folkloric Ballet School (Mexico City,

1968–70, commissioned by Amalia Hernández) is a good example.

There it has to do with how sculptural that building is, and with the movement I was able to produce. The school is basically

an interplay of two opposing forces, upward and downward.

I think more visitors to Mexico City ought to know about your design for the ballet school. Just the intricate window with

the lattice screen is a feat of craftsmanship.

Oh that window! What a piece of work that was. It took thousands of precisely cut pieces

of glass to make. I think it was more labor-intensive than the whole of the rest of the school. It still looks great, though it’s darkened a lot. Sadly, that’s one of my buildings that isn’t very well maintained.

The building is also full of symbology.

Yes. I’ve always been interested in symbols. I even keep a book about the subject on my nightstand. Up until the Renaissance, symbols were used a lot in architecture. Then it stopped, which I think is a shame because it’s a system of meaning that transcends eras and cultures. The square and the circle are universal signifiers

for Earth and time. Other symbols stand for the feminine and the masculine. You have similar representations of opposites with the Aztec and the Chinese. Even the Gothic cathedral is essentially about the union of earth and sky. I don’t see why Modern architecture shouldn’t speak to basic truths that have been part of humanity for so long across so many different places. Take the Colegio Militar, for example. There the building that looks like a mask is based on a temple in Uxmal in Yucatán. I had seen this mask of (Mayan rain deity) Chaac

with protruding eyes and a strong jaw, and it gave me the idea for the school’s director’s office. It was the perfect solution for

an element that needed to have a lot of force,

since that’s where the most important

generals sit. Then a silly rumor started when a picture was published in a gringo magazine showing cadets doing a drill facing that

façade, and people said it was proof that,

in this day and age, Mexican soldiers are still

worshipping a “primitive” god.

-

Folkloric Ballet School, 1968-70. Image courtesy Archivo de Arquitectos Mexicanos (AAM). Fondo Agustín Hernández Navarro. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.

-

Folkloric Ballet School, 1968-70. Image courtesy Archivo de Arquitectos Mexicanos (AAM). Fondo Agustín Hernández Navarro. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.

Mesoamerican ideas of space and building

are the most salient influence in your work. But rather than mimic these shapes, you abstract them and meld them with Modern functionality and maybe a Corbusian sense of volume.

Even though all Mexicans are said to be of two cultures, I have always felt a lot more indigenous than Spanish, so it’s natural

if that comes through in my work. We cannot forget that in this country we are the heirs to a glorious legacy. Whether they were molding built space or empty space, our pre-Columbian ancestors brought a mathematical, almost symphonic rhythm to their cities. I have sought to capture and distill that immense spatial sensitivity in my work.

But at the same time, all architecture

needs to be of its time. I make buildings for

today. I guess that’s why my buildings

feel modern even if they’re rooted in our heritage. Moreover, any form I choose

has to obey a function. Nothing is ever arbitrary. Take the Folkloric Ballet School.

The walls are slanted, which may seem like an aesthetically motivated choice but

actually has to do with optimizing acoustics, since angled walls help avoid the rebound effect of the zapateado (characterized by loud rhythmic footwork), which would be a terrible noise factor for dancers to have to work with day in day out. For me, architecture is the union of structure, form, and function. That’s been my law, as it were.

Some of your shapes also suggest a deep fascination with technology and engineering.

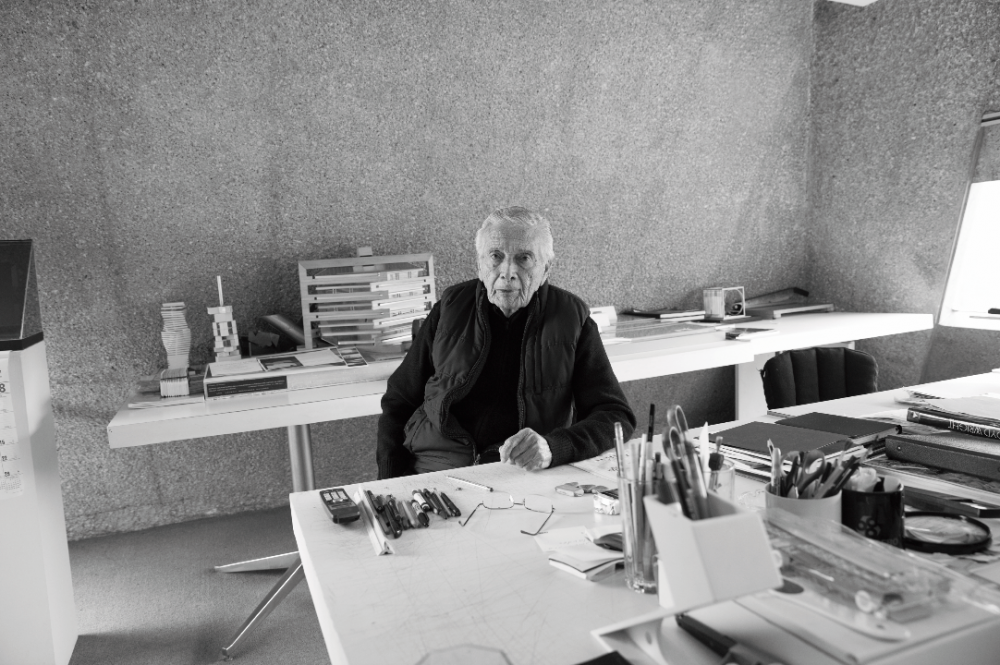

I think that, at the time, my Taller building was

the first to apply the latest suspension techniques. That’s what keeps its walls in place and allowed me to achieve the form I imagined. Even when you see a shape that seems suspended, it is in fact firmly anchored through compression.

Is that what’s helped the Taller withstand Mexico City’s frequent earthquakes?

The Taller doesn’t show a single crack. Though I do get frightened when I’m up there and there’s an earthquake. The building doesn’t oscillate, it’s more of a twist-like motion you feel in there if the earth is shaking. That worries me a bit.

-

Taller de Arquitectura, 1975. Image courtesy Archivo de Arquitectos Mexicanos (AAM). Fondo Agustín Hernández Navarro. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.

-

Taller de Arquitectura, 1975. Image courtesy Archivo de Arquitectos Mexicanos (AAM). Fondo Agustín Hernández Navarro. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.

The Casa en el Aire (Mexico City, 1991)

certainly looks like a science-fiction novel come true, a veritable machine for living.

What happened there is that the clients asked me for something similar to my studio,

and I thought, “Well it can’t be exactly the

same,” so I came up with something that had the appearance they wished for but that made total and unique sense for how they lived. Structure, form, and function had to be

one; therefore, what look like solid walls from the outside actually contain fully functional spaces for various uses. That project is a good example of my guiding principle. The shape you see may be striking, but

it’s not gratuitous.

Your work has been featured in many films. Have you seen any of them?

I’ve seen some of the movies. There’s the one with that German guy, what’s his name?

You mean Arnold Schwarzenegger, the Austrian muscleman, in **Total Recall?

**Right, him! I liked it. And I’ve seen some Mexican films with my buildings in them.

I just never remember the names. My studio is also featured in fashion photo shoots all the time. They fill my office

with models and clothes. Several truckfuls of people and stuff come and stay all day just to shoot a few pictures. It’s crazy.

There was also a hugely successful telenovela in the 1990s called **María Mercedes in which the obligatory female villain lived in one of your buildings — the Taller, I think.

**I forgot about that. But teen idol Luis Miguel filmed a music video at the Colegio Militar. Then they prohibited filming there. As if the school guarded such great secrets!

Does nature ever inform your work?

Sure it does. My studio is in essence a tree — you have the trunk and foliage. The Casa Neckelmann (Mexico City, 1980) is based on the form of a snail. And I often dream

of ocean waves, so they’ve appeared in my sculptures.

What about the role of light in your work?

Light is everything. But I like to enhance

its emotional effect by modulating it,

controlling how it fills a room and affects the feelings of the person inhabiting the space. If you pay attention, you’ll see that in my houses central covered patios are

a recurring feature — in the Casa Álvarez you have a garden with a glass ceiling,

for instance. The goal is to provide each place with what I call a “psycho-biologic” lung. You cannot overestimate the effect on whoever lives there of having a double-height space in a house. Even a small house like the Casa de Adobe (Xalatlaco, 1986), which ended up winning several awards, has a little patio, just four-by-four meters, double height. It’s the house’s lung.

Casa Neckelmann, 1980. Image courtesy Archivo de Arquitectos Mexicanos (AAM). Fondo Agustín Hernández Navarro. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.

It’s interesting you say there’s a practical

justification for all your designs. Sometimes it seems as if you were just realizing a vision you had in a wild

dream. What is the functional reason for

a house that’s totally buried in the ground, like the Casa Neckelmann?

Oh, that was simple. Doris Neckelmann, who commissioned it, wanted a lot of garden space for her kids to play in, but the lot of land we had to build on was quite small. By making the house subterranean, I was able to give her the garden she wanted.

Who has been your favorite client so far?

I think it would be General Cuenca, for whom I designed the Colegio Militar. He let me do whatever I wanted. When I won that competition, all the architects who had submitted designs were in attendance, including some pretty big names. When Cuenca called out my name and “First place!” Mario Pani said to me, “You won yourself a beast Agustín —

good luck feeding it!” He knew it was going to be a challenge to manage such an enormous project, especially given that a lot of generals had a say in it. These were military people, not used to being told how things are

going to be. I actually think I may have adopted a deeper voice to establish my authority and tell them what needed to be done.

Your wife says she barely saw you for months while the school was being built. Did you know this was the commission that would put you on the map?

I was aware that in terms of both quality

and size, this was the job of a lifetime.

It took incredible organizational discipline and stamina. I would drive around the

vast site on my motorcycle all day checking everything, making sure the concrete

was being cast correctly, etc. The scale

and amount of things to oversee was

staggering — just imagine, they asked for

a plaza for military drills twice the size of

the Zócalo (Mexico City’s 500,000-square-foot Plaza de la Constitución).

I can only imagine how dashing you must have looked on your motorcycle. It’s no secret you were very handsome.

That’s why it’s not good for my buildings to

be photographed with me in the frame — even the best architecture can’t compete with my charisma. (Laughs.)

Diego Rivera was a fan of your work, and

supported you early on. Did you know

him well?

Yes, Rivera wrote a big article praising my work. He loved my thesis project. He liked that he could fit it into his nationalist ideology. I didn’t know him too well, but was with him at his studio a couple of times. The thing I remember most about him is his lies. (Laughs.) He enjoyed making up the most fantastical things.

Speaking of men who became myths, I noticed you don’t seem as impressed as the rest

of the world by Luis Barragán. For example, you’re openly and fundamentally against the use of color in architecture — one of Barragán’s major trademarks.

I just don’t think architects should use color to define space. That’s for painters to do. Form is so rich that, if you know how to use it, you don’t need color. For me, color in architecture is like makeup, a trick to get

a result you can achieve with pure volumes. I believe in using light and shadow to highlight the material rather than covering it up. Otherwise it’s just scenography.

Casa en el Aire, 1991. Image courtesy Archivo de Arquitectos Mexicanos (AAM). Fondo Agustín Hernández Navarro. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.

Whose work do you admire? The parallels between your work and Kenzō Tange

are inescapable.

I did like Kenzō Tange a lot, both his work and as a person. Once I had him over at a party

I had at the studio. There were fireworks and

he was jumping around with delight. I like some of Foster’s work. As for Mexican architects, Abraham Zabludovsky and Teodoro González de León were magnificent when

they worked together — their Museo Tamayo (Mexico City, 1979–81) is excellent — but separately, forget it. González de Leon’s Virreyes Tower (Mexico City, 2015) is terrible,

it upsets me. Ricardo Legorreta could have been great if he had stuck to making Modern buildings, but then he fell for Barragánisms, doing houses with thick walls,

all that. It’s a shame he lost his way — he could have been fabulous.

What about Le Corbusier?

He was simply my greatest teacher.

You say that even though you never met him, correct?

Sure, but I have all his books and analyzed him tirelessly.

You’ve said you owe becoming an architect

to your mother, who herself liked designing buildings.

It’s true. My mother would have liked to

be an architect herself, if she could have.

She was a teacher, like her mother had been, but had an innate interest in buildings,

and designed several houses and then hired men to build them for her. My mother made my older brother study architecture. I wanted to be a mechanical engineer because I wanted to build things, not necessarily houses. But my mother said, “No. You have to become an architect like your brother.” But she never liked what I did. (Laughs.) Her taste was too conservative.

It’s fine because I find the house she made for herself in Cuernavaca horrible.

Of all your built designs, which is dearest

to you?

I love Calakmul, I think it’s my favorite. I like

it because it’s different to everything

and it really illustrates my philosophy.

Does it bother you that people call it the washing machine?

No. One time the daughter of a president

said to me, “You know what they call

your building? The washing machine. And

you know why? Because it was used

to wash dirty money.” Just imagine, the daughter of the head of state making

a comment about how corrupt our government is. I thought it was clever, and it

made me see the nickname in another way.

One of your lesser-known works is a sort of Zen retreat on a hill in Cuernavaca (Centro de Meditación, 1986). I think it’s abandoned now, but it’s still maybe one of the

projects that best expresses your interest in symbolism.

That building was for my sister who had

a meditation group, and they needed a

place where they could meditate. A local priest lived nearby and hated the building

I designed. He thought I’d made some

sort of demonic monster and was furious, just because I designed it in the form

of a serpent! And you enter the building through the serpent’s mouth, which

was not unusual in pre-Hispanic temples.

Agustín Hernández photographed by Dorian Ulises López Macías for PIN–UP.

Would you describe your work as emotional?

I don’t know. But there was this time when

a lady entered the meditation center

and flung herself on the floor in some sort of shock state, and they said it was because the space had affected her

so much. So maybe my buildings do have magical powers. Tell me something,

do you know what type of aircraft you’re flying back to New York in?

I’m not sure yet. But I can find out. You’re obsessed with planes and cars, no?

You also used to be an avid horseback rider. Is it the speed you’re interested in?

I loved riding horses, until, through my kids, I discovered cross-country motorcycle racing and traded horses for that. I was also a pretty decent polo player when

I was younger. It’s all about fun. Architecture and work matter, but not more than having fun and living life. You can’t just be thinking about buildings. You have to care about other things. That way you relate to others first as a human being and then as an architect. I still love cars. Not too long ago

I got some prize money from the military and used it to buy a new Mercedes. But my wife won’t get into it.

She told me she’s afraid of being in the car with you if you’re driving because you’re always imagining projects and getting

distracted from the road.

She’s probably right. I like to say I owe the periférico (Mexico City’s orbital highway) my career, because a lot of ideas come to me while driving and being in traffic, and I’ve spent countless hours on the periférico. I’m definitely a contemplative person — that’s my design approach. The first time it happened — where I saw something and was carried away envisioning a building that didn’t exist yet — was with the Taller.

How do you want to be remembered?

For me, the Colegio Militar is my greatest accomplishment, not just the buildings

but how I planned the whole complex, which is actually quite Corbusian with

its central axis. I think one of the most

difficult things in architecture is to design

a project with an encyclopedic list

of requirements, and the program for the academy was like a phone book. There’s

a hospital, a church, a supermarket, everything you can imagine, like a proper city.

It’s 4.3 million square feet of built space.

If it was 20 by 20 meters, it would be

a 100-story tower.

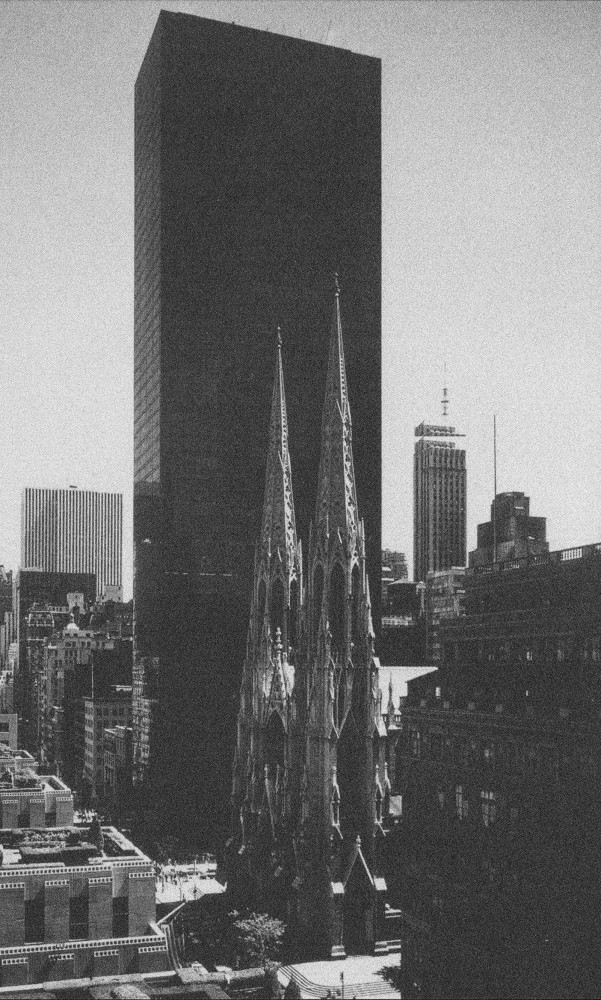

Why did you never build a skyscraper?

It just never happened. I would have liked to — I have some models, but they’ve remained unrealized. Maybe one day.

Text by Suleman Anaya.

Portraits by Dorian Ulises López Macías for PIN–UP.

Work images courtesy Archivo de Arquitectos Mexicanos (AAM), Fondo Agustín Hernández Navarro, and Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.