LIGHT READING: Discover The Surprisingly Frilly Silk Lamps of Early Modernism

Despite what some historians would have you believe, the 20th-century Modern movement was not a uniform style of all-white walls, utilitarianism, and exposed light bulbs. Between 1900 and 1939, the period when Modernism crystallized, a ubiquitous oddity stands out: simple decorative lamps incorporating shades of lustrous silk. Some perceived these lamps — predominant in but not exclusive to Vienna — as old-fashioned and in opposition to Modernism’s avant-garde ideals. But they broke tradition in their own way through their use of plain white silk — no patterns or decoration — which imbued them with sensuality, the fabric gently diffusing the intense light of the bulb so that, instead of harsh illumination and shadows, they gave out a soft, homogeneous glow that went beyond the merely functional to create a mood.

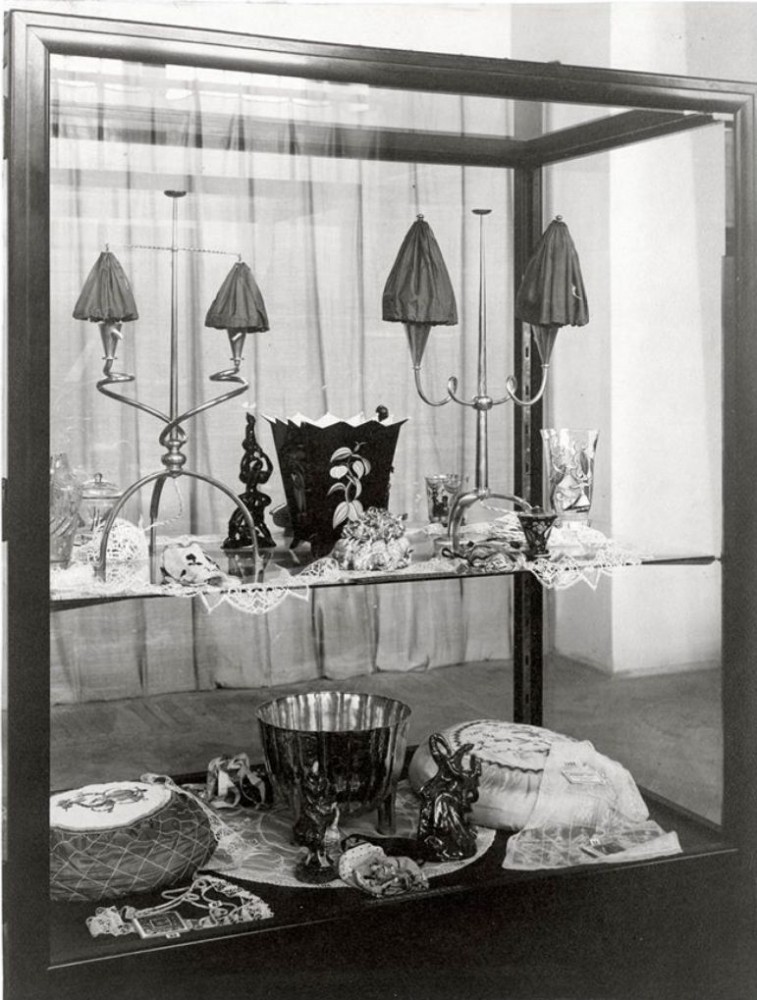

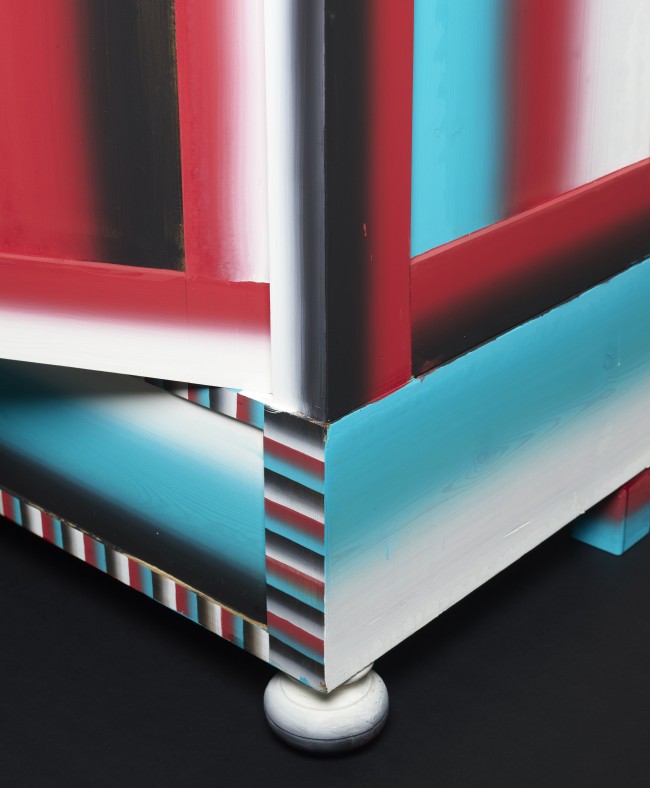

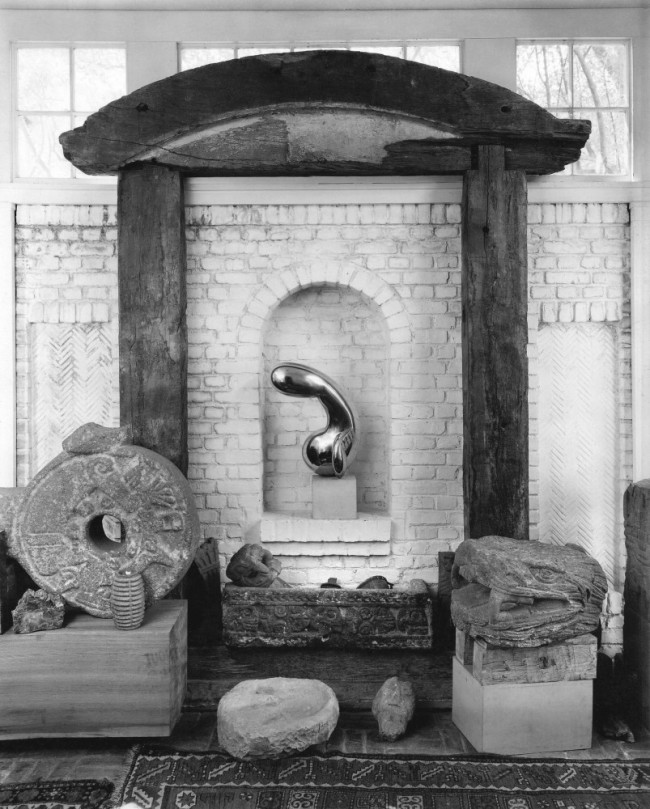

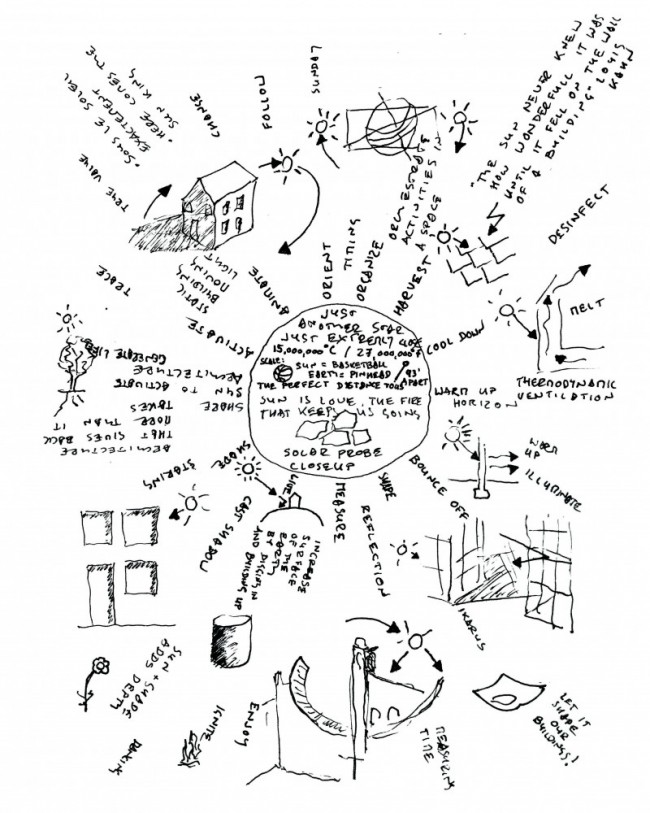

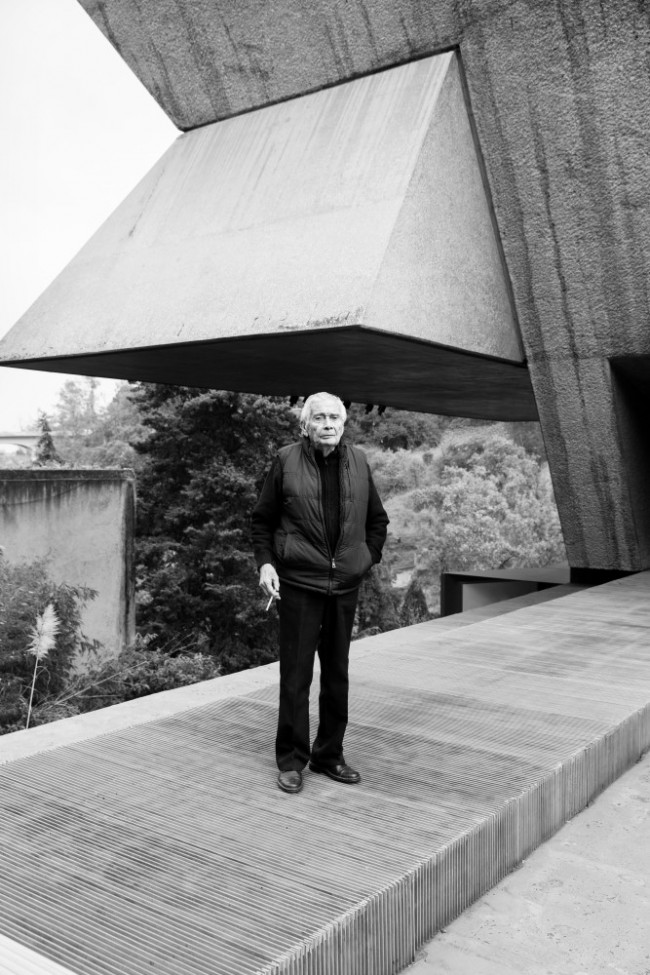

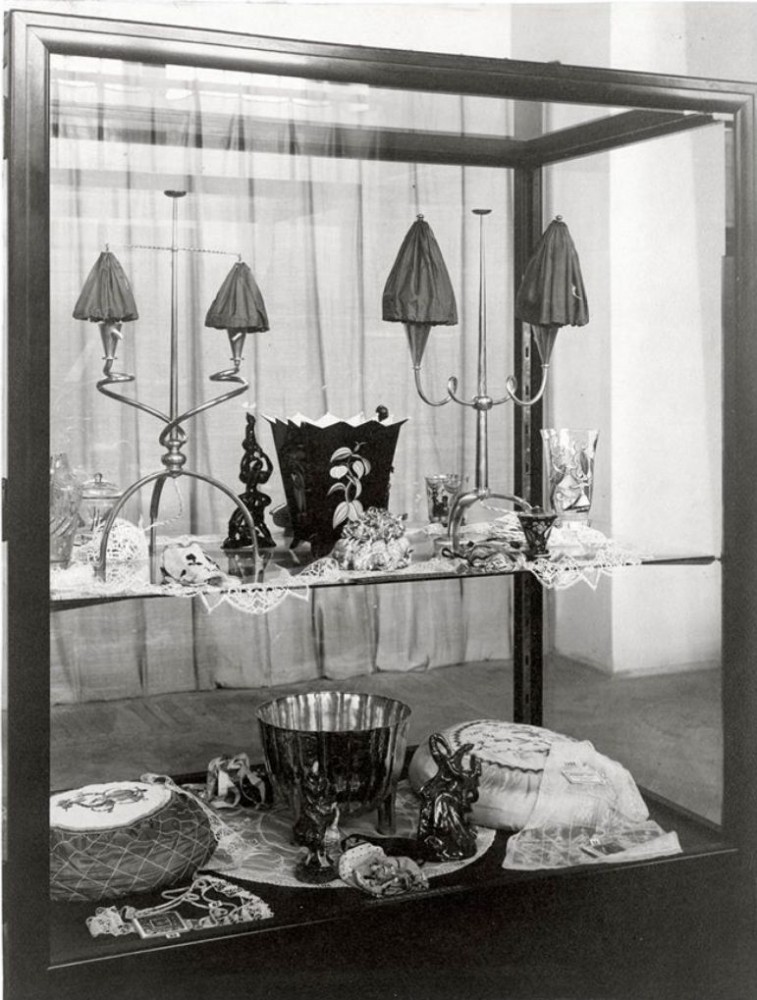

Wiener Werkstätte showcase organized by Otto Prutscher in 1920. © MAK. Taken from PIN-UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

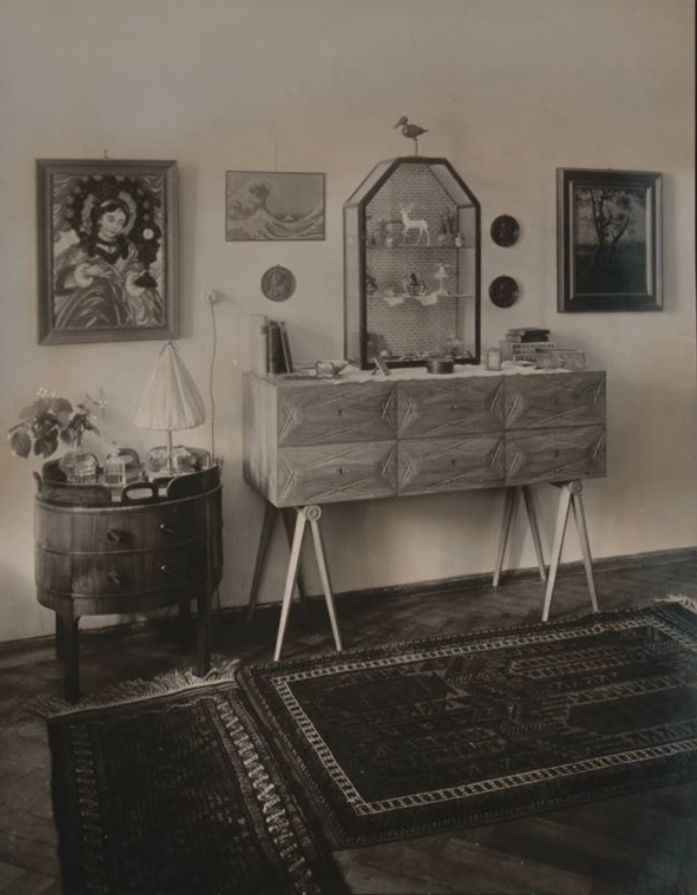

As is apparent from German-language publications of the time (for example Innen-Dekoration or Das Interieur, both founded in 1900), the extensive use of silk lamps in Viennese interiors was not uniform, nor did it respond to a clear manifesto or predefined style. Schematically, two main approaches can be identified. On the one hand, the fashionable and exquisite style of the Wiener Werkstätte — a cooperative, in operation from 1903 to 1932, that was founded by the designer and painter Koloman Moser, the architect Josef Hoffmann, and the industrialist and arts patron Fritz Wärndorfer — which strove to achieve a Gesamtkunstwerk of everyday objects in the home and produced some of the most stunning silk lamps of the time. The Werkstätte proposed numerous models in their extensive catalogue of household objects, which were also available in their shops, and Hoffmann himself used Werkstätte lamps in many of his interiors, such as the writing room at the Sanatorium Purkersdorf just outside Vienna (1904–05) or the salons of his most ambitious work, the Palais Stoclet in Brussels (1905–11).

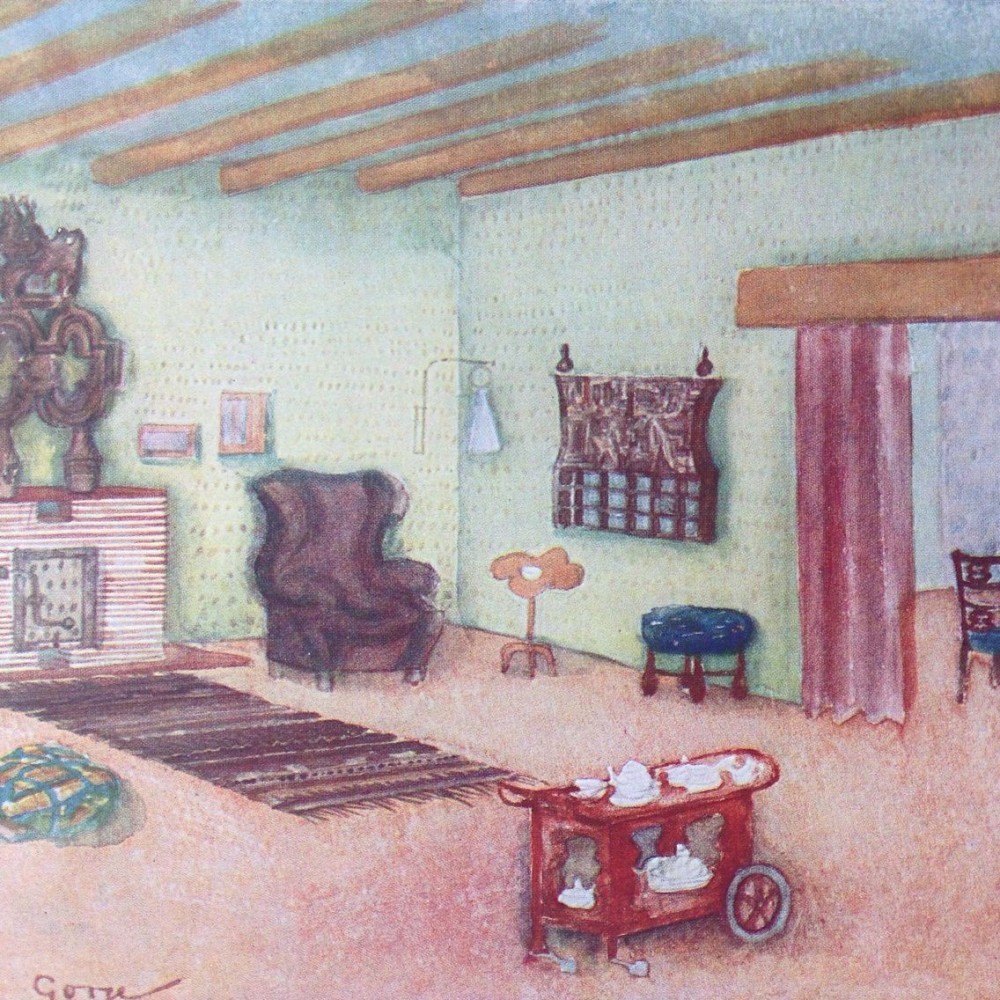

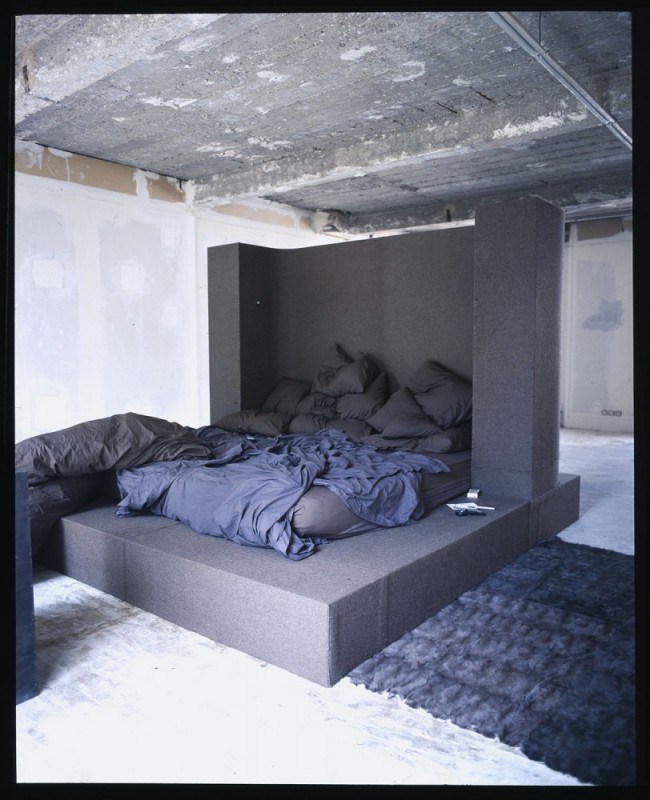

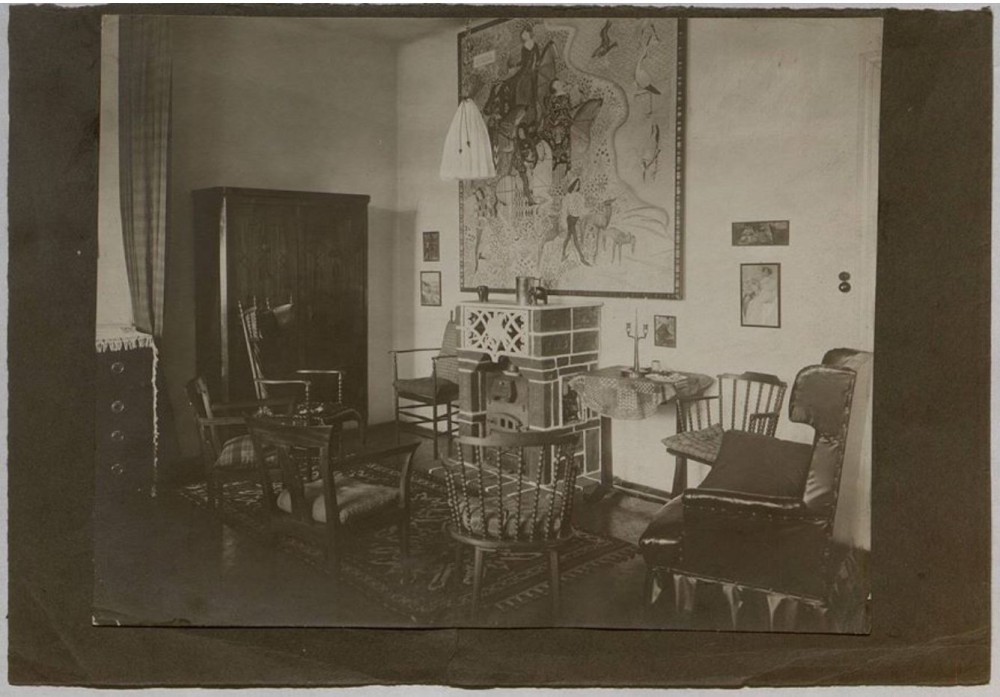

Then there was the approach adopted, around 1910, by a group of architects of which Josef Frank (who was also a member of the Wiener Werkstätte), Oskar Strnad, and Hugo Gorge were the most prominent members, and which took to heart some of the ideas put forward by Adolf Loos. Openly opposed to the creative universe of Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstätte, which he regularly attacked in print, Loos proposed instead a subjective attitude of renewal that defended the autonomy of the inhabitant against the tyranny imposed by styles and ornament, as set forth in his famous 1910 lecture Ornament und Verbrechen (Ornament and Crime). For this group, the silk lamp wasn’t just a stylistic anachronism or a mere fad, but part of a more human-centered approach to Modern design that rejected functionalist ideals in favor of what would come to be called Wiener Wohnkultur (Viennese culture of living). Frank, for example, eschewed the use of tubular-steel furniture, which to him merely represented a modern version of an overly prescriptive bourgeois style. The use of silk lamps and other artistically valuable textiles preserved the old ideal of home as a site of enlightenment and refuge, connecting with the pre-industrial world, but without, however, the slightest desire for historicism. Through his writings, designs, and interiors, Frank proposed a methodology based on the essential conditions of living, giving priority to the physical and emotional well-being of the inhabitant. His stance towards modernity could be defined as a domestic resistance to the radical renewal proposed by those who sought to invent a new Modern style. Similarly, Strnad and Gorge explored the symbolic dimension of these design objects, connecting them to the uncertain and not immediately perceptible emotional world. While this affect-driven perspective helps us understand the particularities of a distinct Viennese sensibility founded on a longstanding sense of tactile pleasure (something that a material like silk amply provides), it also invites us to reconsider these lamps as exemplary of a reaction to a functionalist strand of Modernism that was not, despite the claims made for it by its advocates, inevitable or self-evident.

-

Brass and silk lamp designed by Josef Frank for the Villa Wittgenstein. Manufactured by the Wiener Werkstätte. Courtesy of 1st Dibs.

-

Brass and silk lamp designed by Josef Frank for the Villa Pickler in Budapest, Hungary (1909). Manufactured by the Wiener Werkstätte. Courtesy of 1st Dibs.

-

Patinated brass and silk chandelier by Josef Frank for the residence of the Banker Dr Dietrich Moldauer. Courtesy of 1st Dibs.

-

Hammered brass and silk lamp designed by Josef Frank. Manufactured by the Wiener Werkstätte. Courtesy of 1st Dibs.

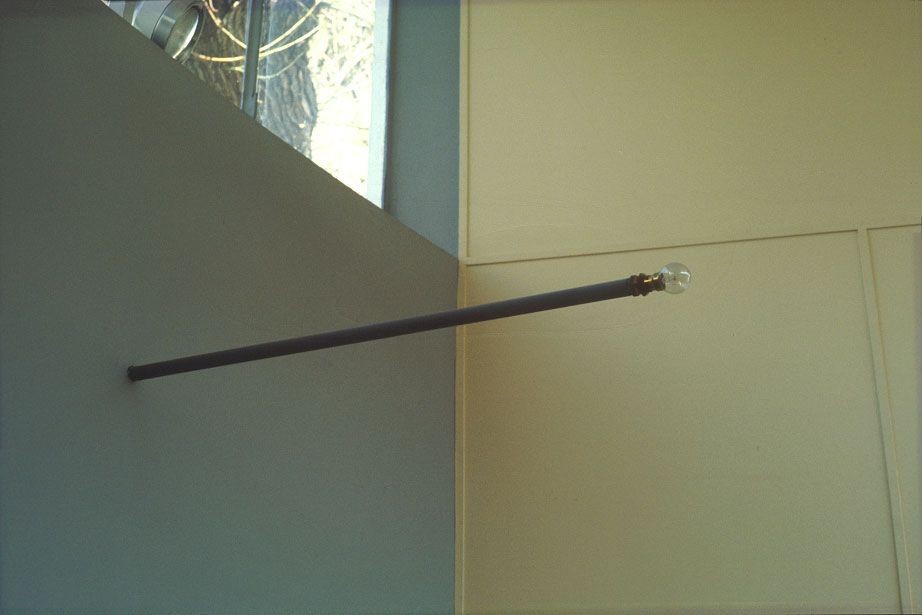

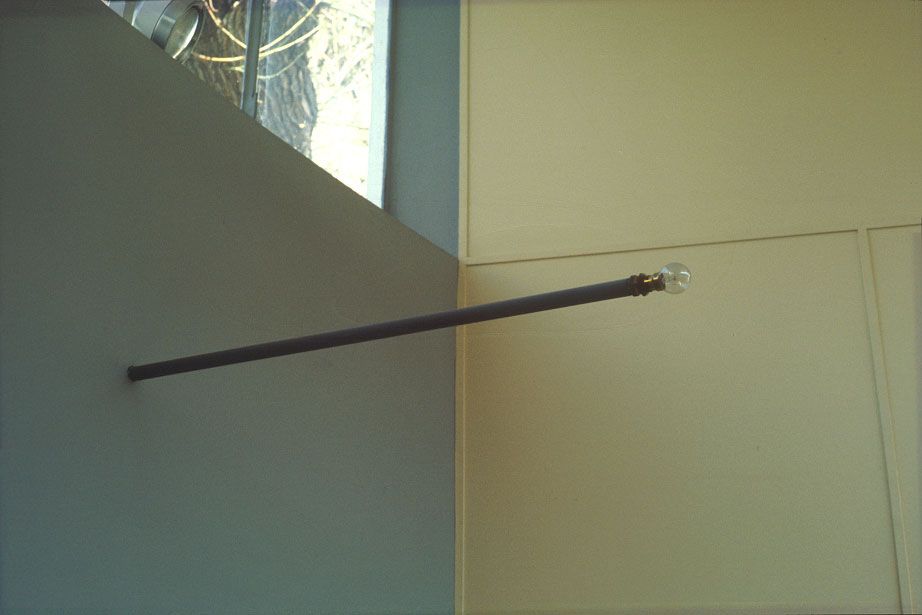

At the dawn of the 20th century, a new attitude towards interior lighting emerged. Whereas, in the 19th century, both electric and oil lamps had been regarded as an integral decorative and expressive part of any interior, lighting was becoming ever more standardized: reduced to mere technical considerations, it came to occupy a paradoxical position between the austerity of social-housing projects and the luxurious salons of the haute bourgeoisie, and as such was a vessel for the inherent contradictions of the period. Most Modern architecture was designed for sunlight — to be lived in (and photographed) by day. But what of the night? Some Modernist masters, such as Le Corbusier, tended towards a minimalist approach: his 1925 Villa La Roche in Paris, for example, had very little fixed lighting when first completed. While stumbling through the dark house at night cannot have been an amusing experience for its owner Raoul La Roche, he nonetheless seems to have been remarkably indulgent towards the inflexibility of Le Corbusier’s machine à habiter ideal, which presumably, compelled by the rationalist approach, reserved the night for sleeping and little else. But only a decade earlier, in 1912, the same Le Corbusier — then still known as Charles-Édouard Jeanneret — had used silk lamps, wallpaper, and all sorts of textiles for the interior of his first solo building, the Maison Blanche, also known as the Villa Jeanneret-Perret, the house he designed for his parents in his hometown of La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland. The evolution in Le Corbusier’s choice of lighting suggests a move towards the radical and the avant-garde, reinforcing the illusion of a historical rupture with which the Modern movement is assimilated. In contrast, the use of silk lamps in the Viennese context offers an alternative narrative, contradicting an ideology in which comfort and Gemütlichkeit seemed no longer to have any place.

Wall lamp at Villa La Roche (1923–25) designed by Le Corbusier. Photography c. 1975. Taken from PIN-UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

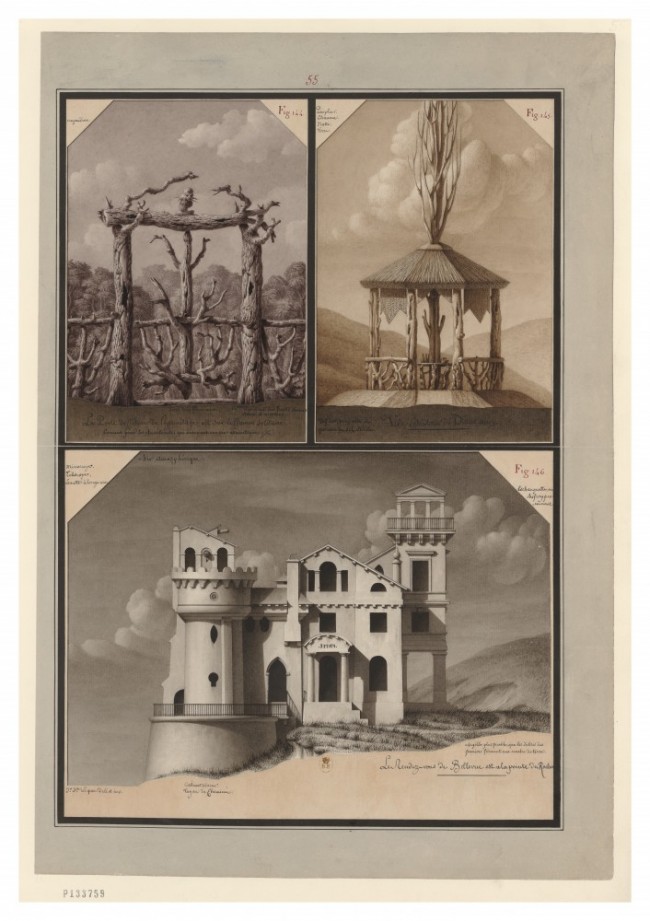

In 1907, the artists of the Wiener Werkstätte designed the Cabaret Fledermaus in the heart of Vienna, one of the cooperative’s most famous projects. The cabaret closed in 1913, but among the records that remain of it is a detailed sketch by Le Corbusier, which he drew from memory: in it, and in surviving photographs, we can identify rectangular silver wall and table lamps covered with a fine and almost translucent silk. Just a year later, Loos used a very similar design for the wall lamps at the American Bar in Vienna, and they would become a common sight in many of the city’s apartments and villas. Silk’s lightness and sophisticated appearance belie the simplicity of the objects themselves — generally just a brass foot with a rod of some sort to carry the bulb. But there is something uniquely beautiful in the tension between the cold metal, the warm light, and the fragile fabric. These silk lamps are just one example of the specific way in which the Wiener Werkstätte determined the taste and direction of early Modernism in Austria and beyond, even if its influence on interwar Europe is often overshadowed in historical accounts by the more imposing vision of the Bauhaus and its ilk.

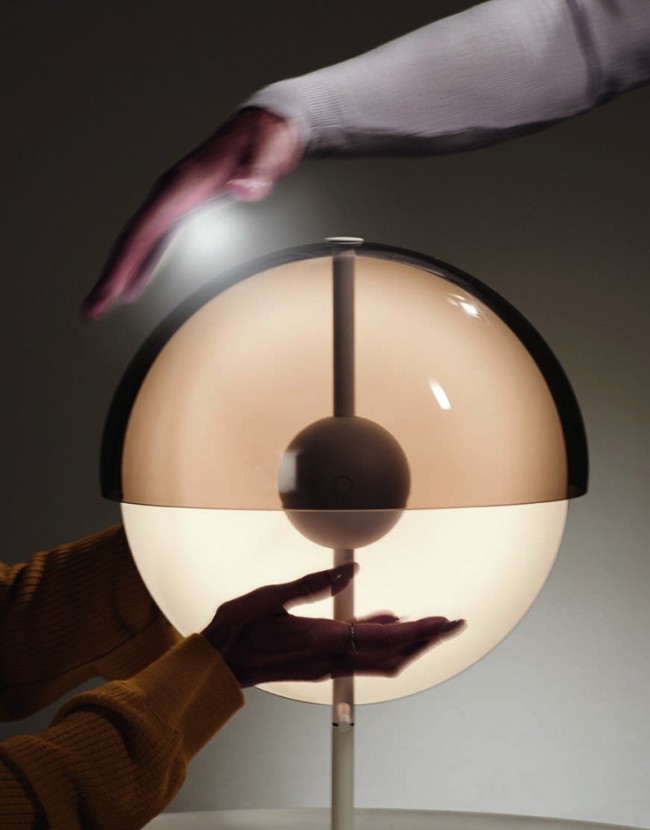

What should modern lamps look like? That was the rhetorical question Strnad asked in his famous 1914 lecture, Vom Licht, vom Besteck und Geschirr, von den Stoffen und den Teppichen, also auch vom Ornament (On Light, on Cutlery and Crockery, on Fabrics and Carpets, so also on Ornament). While Strnad failed to offer an answer, many later representative figures of the Modern movement tried. Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, et al. all made attempts to integrate simple lighting systems into their interiors with varying degrees of success, to a man favoring a decidedly industrial aesthetic. In this context, we can read silk lamps as a subtle rebuke to the fetishization of the Modern lamp as a standardized object, a pushback against the puritanical homogenization of interiors — and by extension their inhabitants — that such an approach implied. While Strnad never specified what a modern lamp should be, his lecture does clarify what it shouldn’t: “Then such atrocities arise, which our industry considers the latest creations in the field of ‘modern,’” he declaimed, railing against the industrial aesthetic in lighting design. Nor did he fully endorse silk lamps, describing their use as “a feminine gesture.”

Brass and silk lamp designed by Josef Frank, manufactured by the Wiener Werkstätte 1919. © MAK/Georg Mayer. Taken from PIN-UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

Though Strnad didn’t employ silk lamps as often as Frank or Gorge, all three shared a similar understanding of textiles as an essential part of a more human, intimate approach to designing interiors of cosmopolitan comfort. Frank, in his 1934 article “Rooms and Furnishings” (originally published as “Rum och inredning” in the Swedish Handicraft Association’s magazine Form), explained his interior design choices — which included, of course, lamps — in terms of their enigmatic quality:

Everything that can arouse our interest (and that should be every object in our home, otherwise they do not serve to express a personal relationship and remain dead) must in some way be a mystery to us, must conceal something secretive, that we cannot get to the bottom of. Every work of art is puzzle. This can only apply to a useful object because of its shape, the technique used to make it, its construction, ornamentation, or origin, as it is the product of a process of thought that is for us unfamiliar and unfathomable. That is why we have a particular fondness for strange objects.

Gorge went furthest in exploring the metaphysical qualities of silk lamps, studying their symbolic implications and enigmatic effects. Sometimes they are subtly incorporated into the composition of the room, at others they forcefully stand out, flaunting their graceful and decorative attitude. In many cases, their small proportions reinforce their otherworldly appearance, such as Gorge’s 1924 nightstand lamp that mimics the form and mobility of handheld candelabra and oil lamps, gesturing towards a more inclusive, humanistic Modernism that doesn’t sacrifice warmth or comfort — a celebration of the objet-sentiment (sentiment object) that Le Corbusier would come to deride (and to which he preferred the objet-outil (tool object)). As historian Christopher Long put it, when analyzing Frank’s ideas, “A reading lamp for a home not only illuminates, but through its design, material, and construction also brings joy and solace,” unlike the industrial workplace lamp, which was merely required to provide sufficient light for the task at hand.

Table lamp by Hugo Gorge at the 1925 International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. © MAK. Taken from PIN-UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

In its day, the silk-lamp typology raised more questions than it provided answers, yet through its contradiction it continues to elucidate specific conditions of Modern architecture and design history. Transcending mere technical function, the Viennese silk lamp, through its enigmatic and expressive grace, challenges the dominant narrative of austerity that historians generally ascribe to the period. The fact that fabric lampshades are ubiquitous today reminds us of the timeless properties of flexible textiles. With its uniquely playful character and lustrous texture, silk successfully served to materialize the formal and expressive fantasies of the Wiener Werkstätte, while at the same time helping Frank, Gorge, and Strnad formulate a distinctly moderate reaction to the needs of their time and assert their rejection of the industrial aesthetic. It can also be read as demonstrative of their desire to ensure that fragile connection with one’s own home that Henri Focillon so deftly encapsulated in his poetic text Éloge des lampes (In Praise of Lamps, first published posthumously in 1945): “Le soleil est un chef-d’œuvre public. Ma lampe, ce trésor, n’appartient qu’a moi” (“The sun is a public masterpiece. My lamp, this little treasure, belongs only to me”). It is in the solitude of the night that these creations unveil their true magic, demonstrating silk’s ability to render harsh electric light naturalistic, as well its power to conjure up the mysterious and the unknown.

Text by Adrián Prieto.

Adrián Prieto is an architectural historian, writer, and creator based in Vienna. He is currently working on a PhD exploring the cross-cultural relationships within Modern architecture and design.

Taken from PIN-UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.