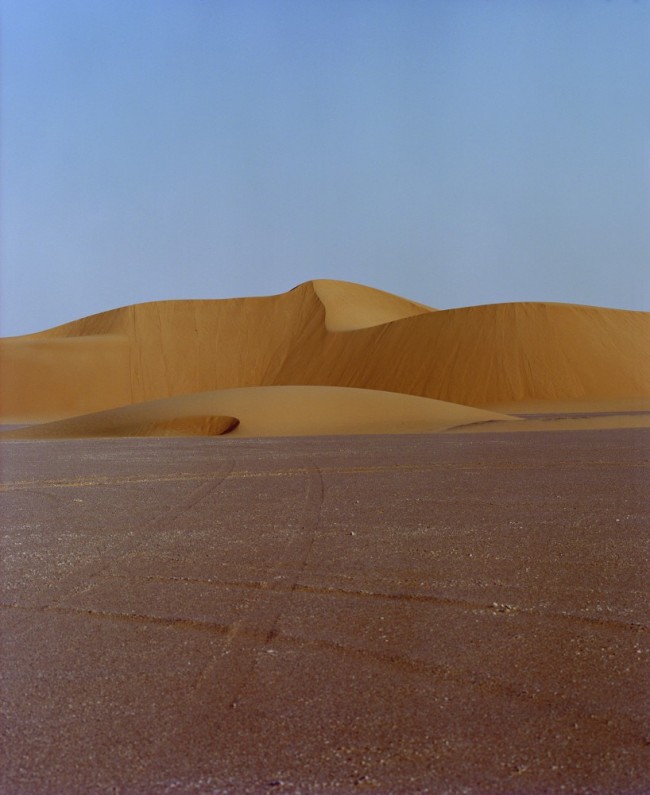

BOOK CLUB: Arthur Elrod, Desert Decorator

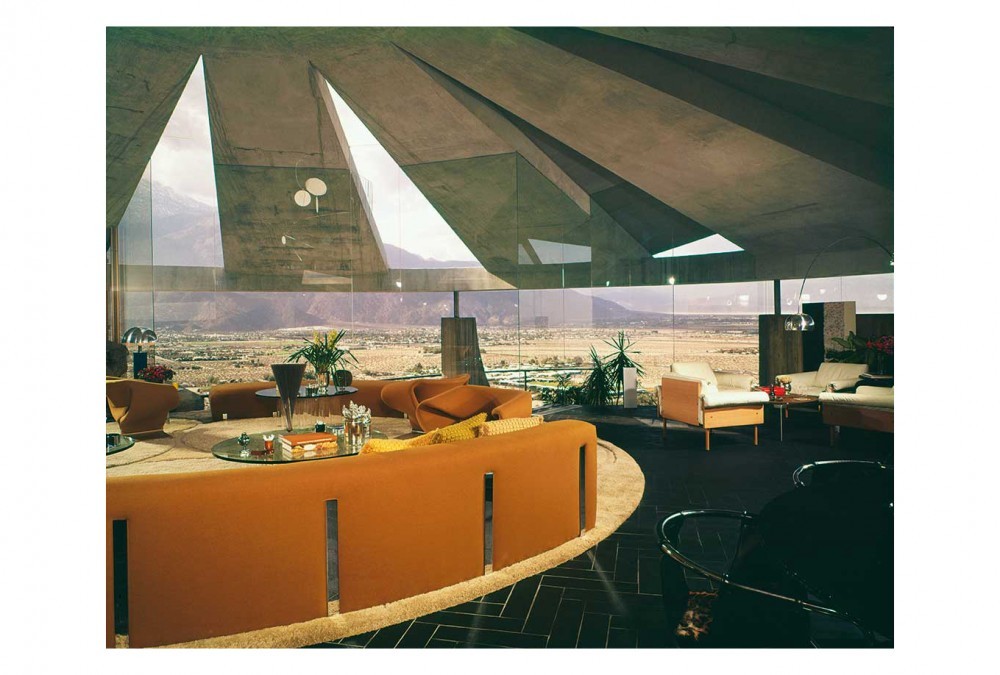

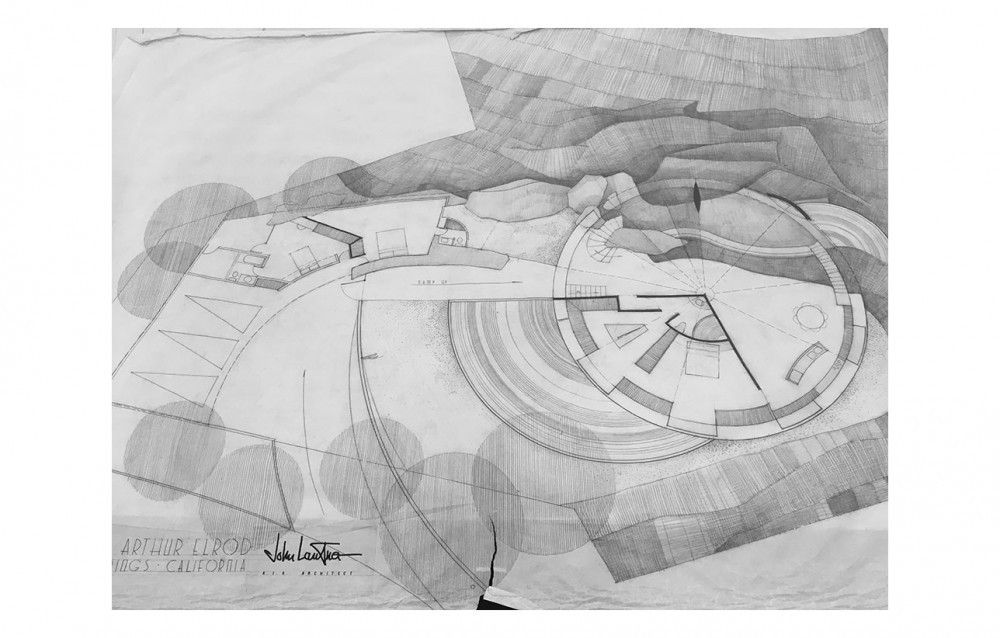

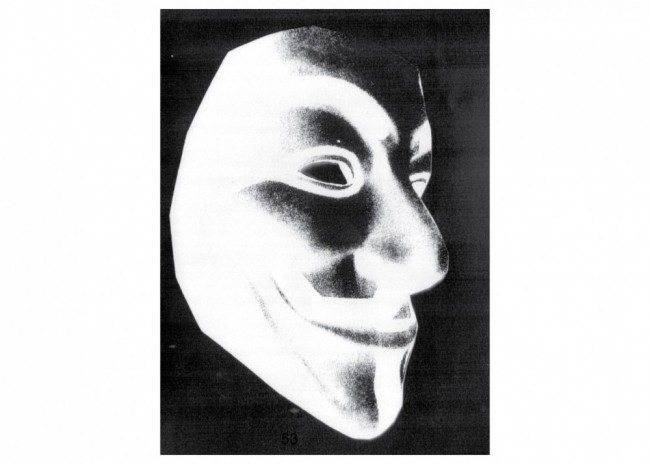

The first monograph about Arthur Elrod (1924–74), the celebrated Palm Springs interior designer, portrays his rise to prominence as a Bildungsroman about metamorphosis, even glamorization. Known as the “design king of the desert” for his prolific work during the town’s post-war housing boom, Elrod is particularly remembered today as the client behind the concrete-domed hilltop dwelling that John Lautner custom-built for him in 1968. “Give me what you think I should have on this lot,” Elrod is supposed to have exclaimed by way of a brief, perhaps indicative of his confidence that his decoration would define the space in spite of Lautner’s expressionist architecture. But, as Adele Cygelman’s new 224-page book, Arthur Elrod: Desert Modern Design, reveals, the designer didn’t always work in the James Bond style that his eponymous Palms Spring home, star of Diamonds Are Forever, evokes.

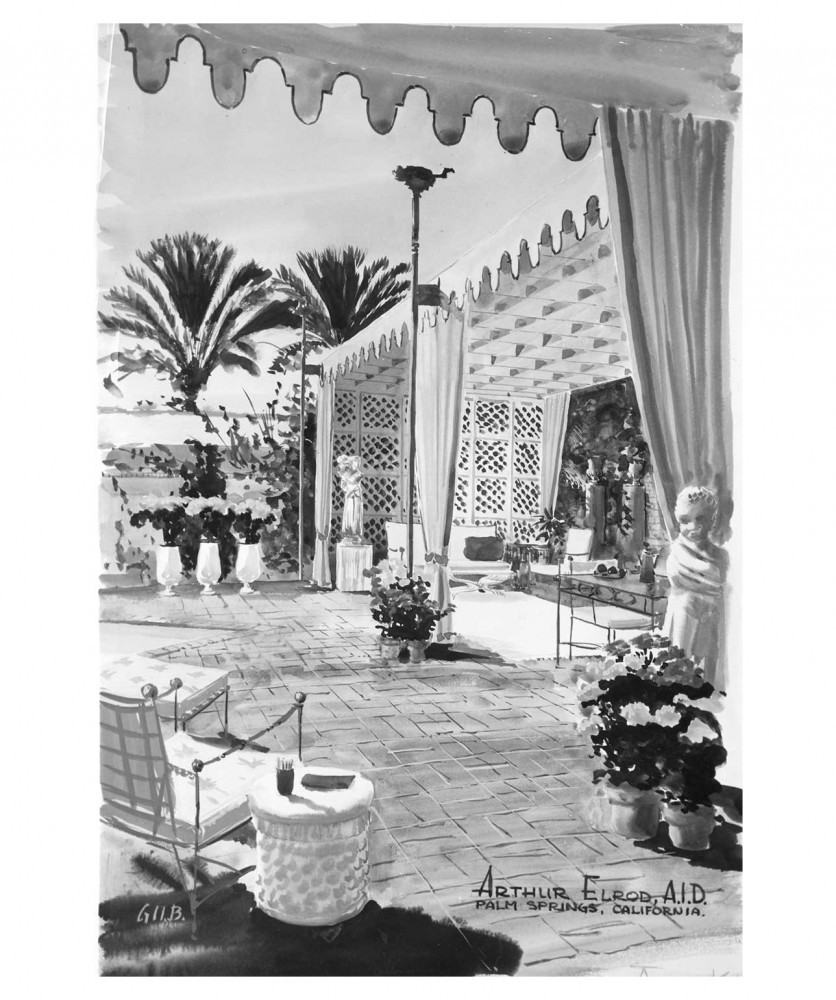

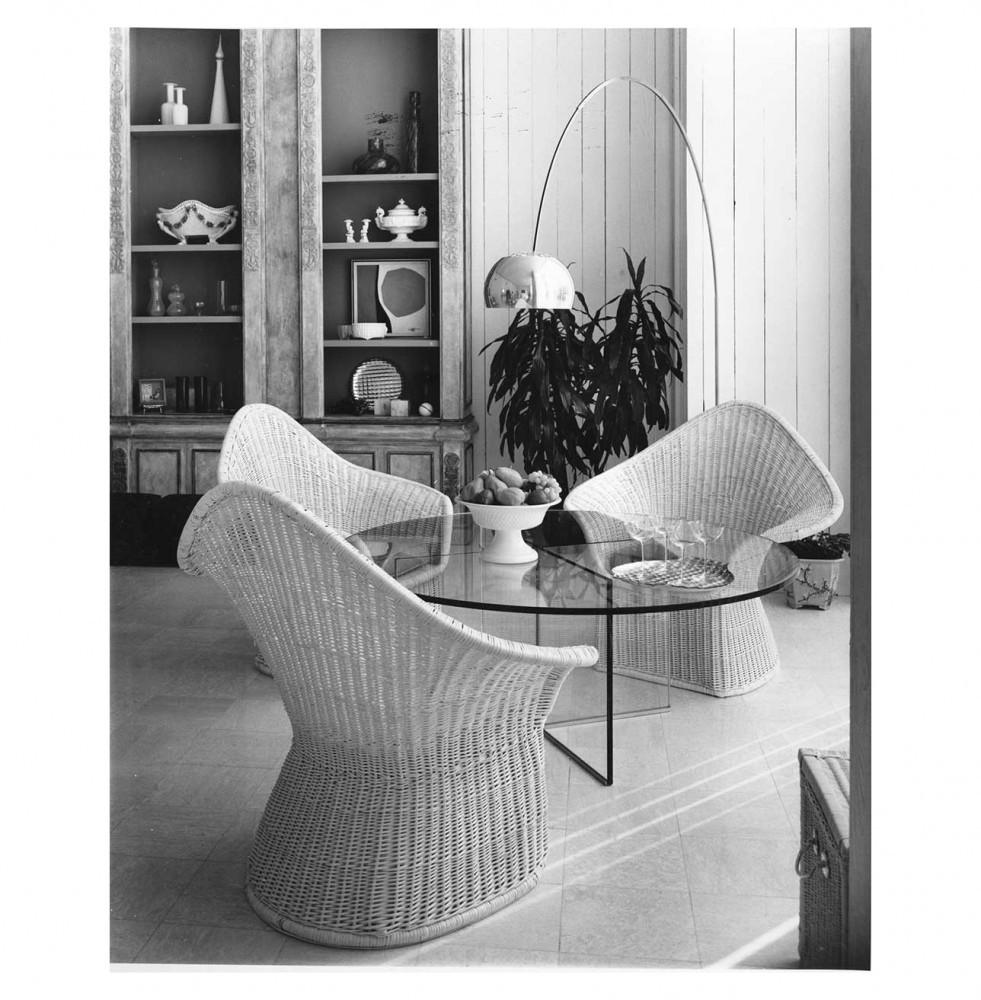

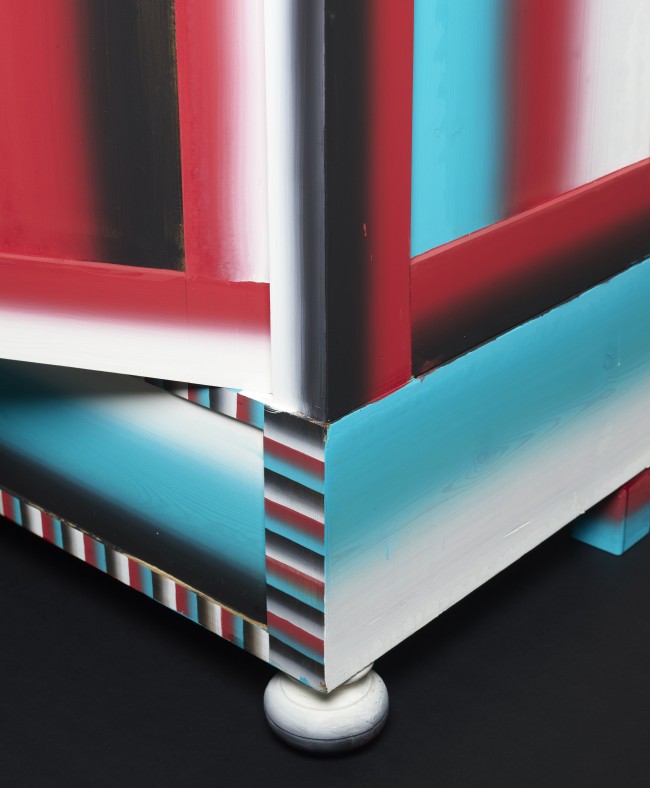

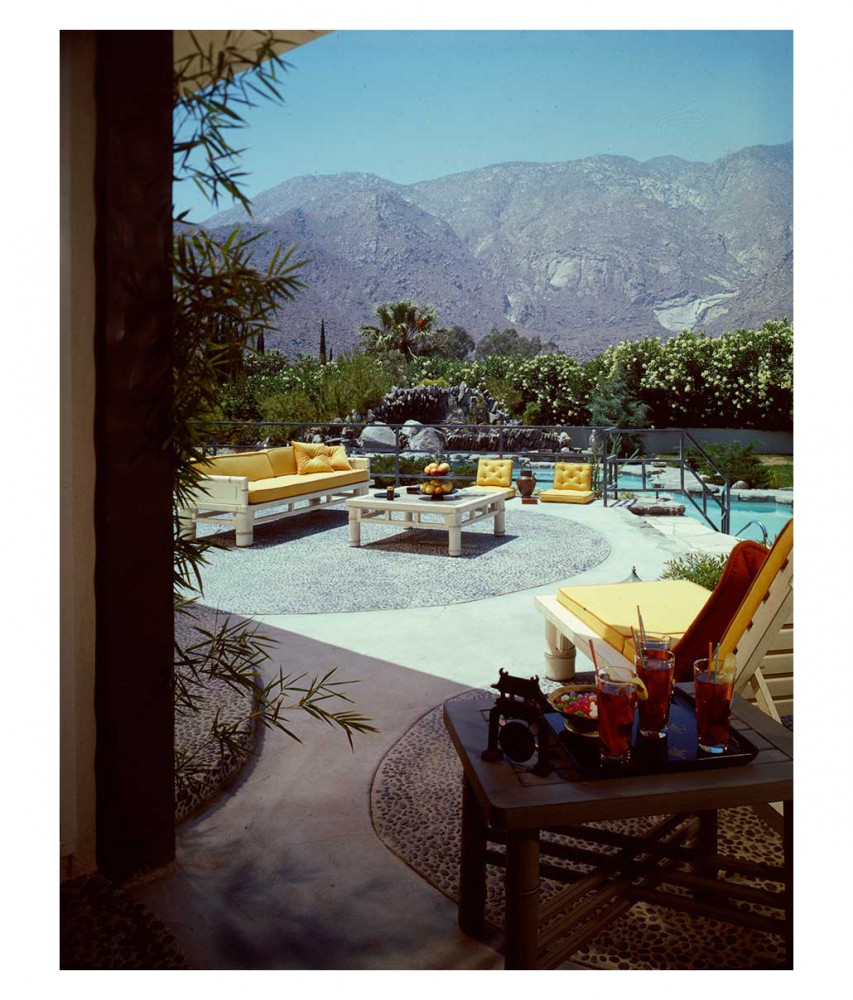

ARTHUR ELROD HOUSE I

419 Valmonte Sur, Movie Colony

In his early years, Elrod clung to pastoral fantasies, attracting a conservative clientele that included Walt and Lillian Disney, as well as composer Hoagy Carmichael. To be sure, trends change over time, but even Cygelman can’t avoid cringing at what she humorously describes as a style that channeled “the rustic country houses of Provence by way of New England” and involved a grotesque amalgam of cypress wall paneling, braided-wool rugs, Windsor chairs, and floral curtains that always matched cushions and bedspreads — a nostalgic visit to grandma’s, in other words.

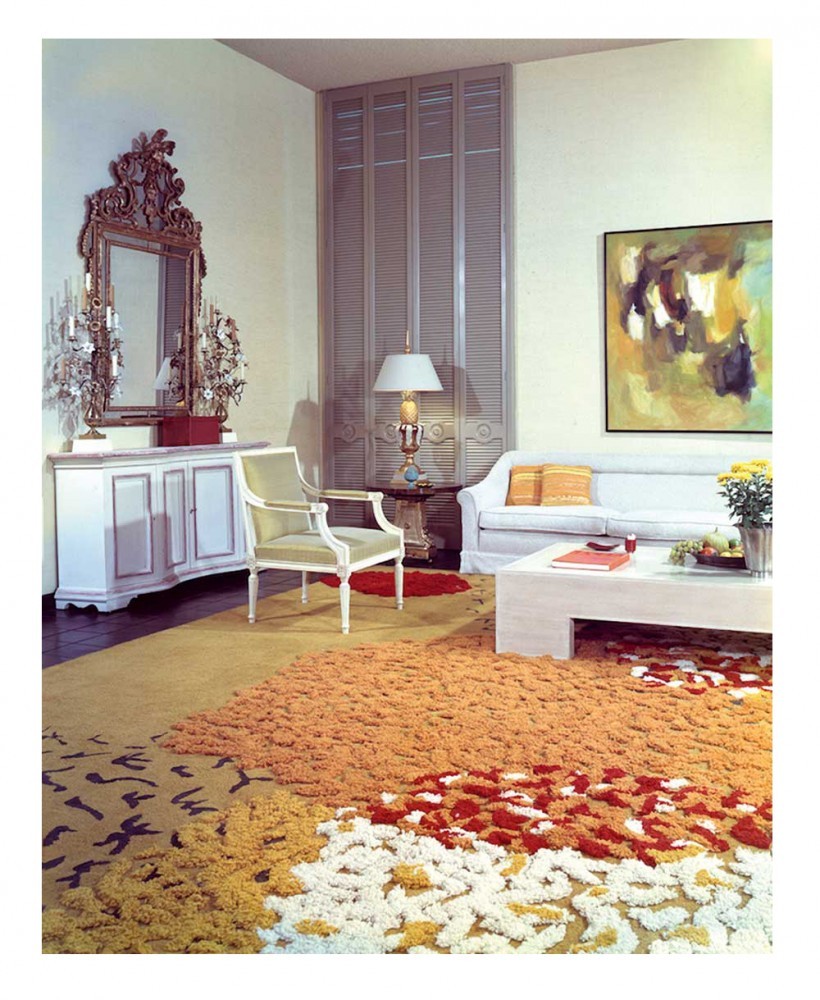

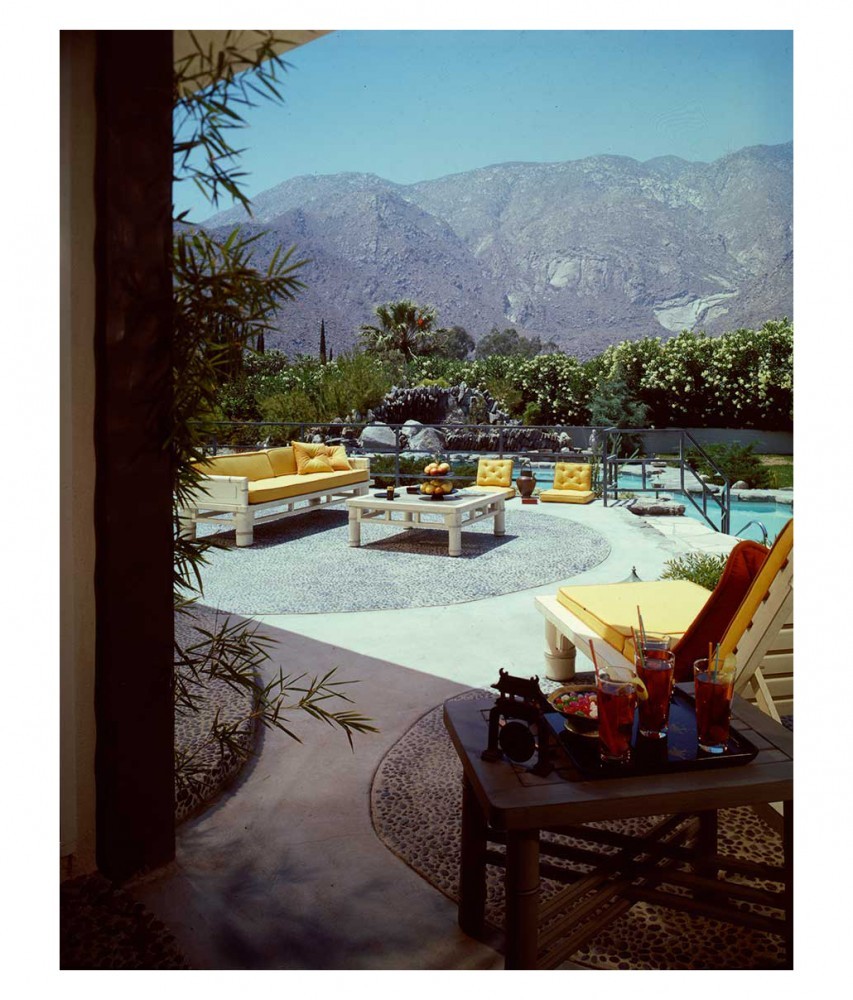

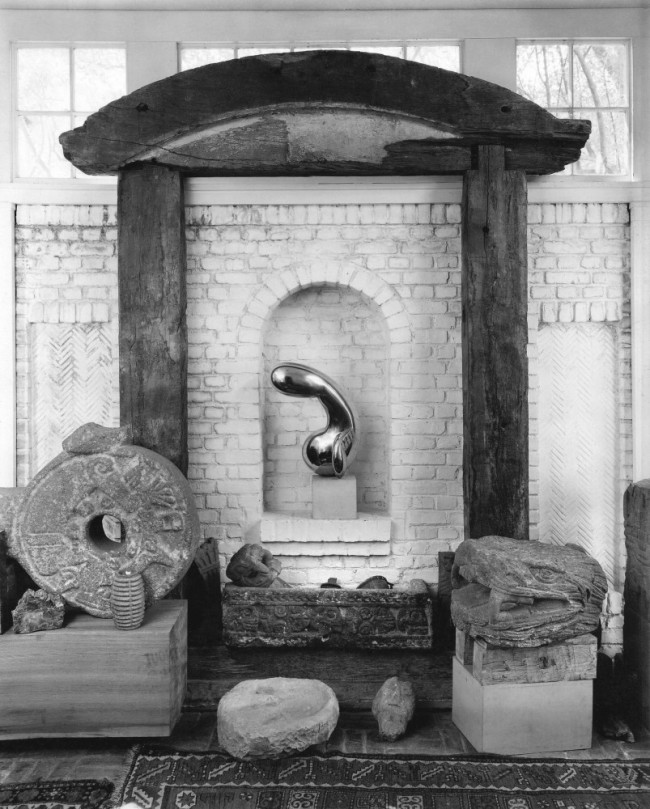

ALTA AND ROY G. WOODS HOUSE (1960)

40995 Thunderbird Road, Thunderbird Heights, Rancho Mirage

Cygelman has more admiration for Elrod’s business savvy during these “pre-modern” years. At a time when Hollywood’s elite was seeking the prime location for its second homes, Elrod bought up cheap properties in Palm Springs, refurbished them, and then flipped them at higher rates, effectively turning a profit while advertising his design practice. To augment yet further his visibility, and eager to cast himself as an authority on all things design-related, Elrod wrote his own column in Palm Springs Villager magazine and took on the role of editor of the desert-living section of Palm Springs Life. By 1959, tides were turning, and if he wanted to keep his credibility as a design authority, he needed to embrace Modernism. As he remarked to the Los Angeles Times that same year, “The mark of perfection in decorating must remain — as it does in any lines of art and design — an understatement.”

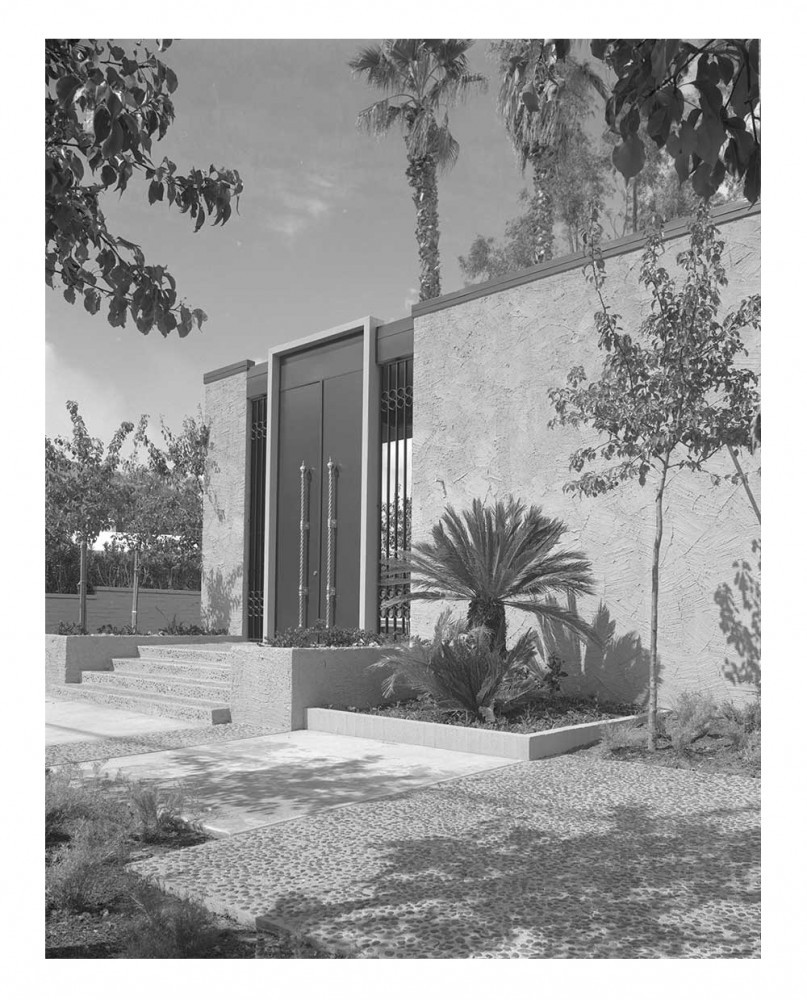

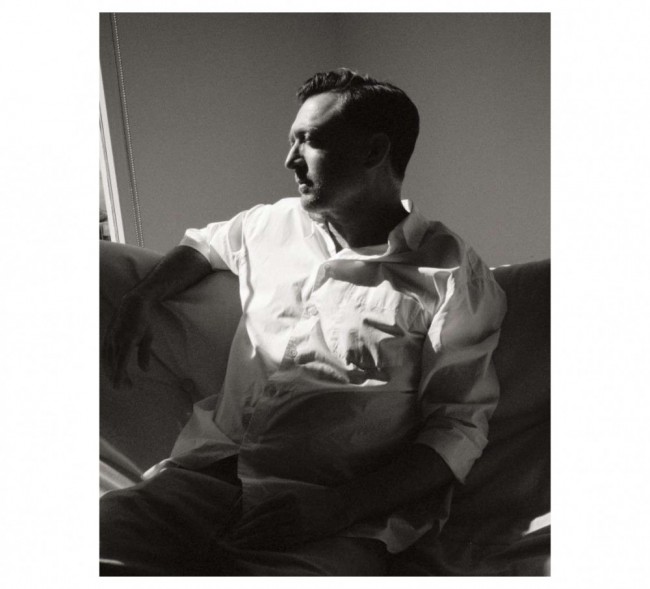

ERNEST AND LEONORE ALSCHULER HOUSE

425 Via Lolas, Old Las Palmas

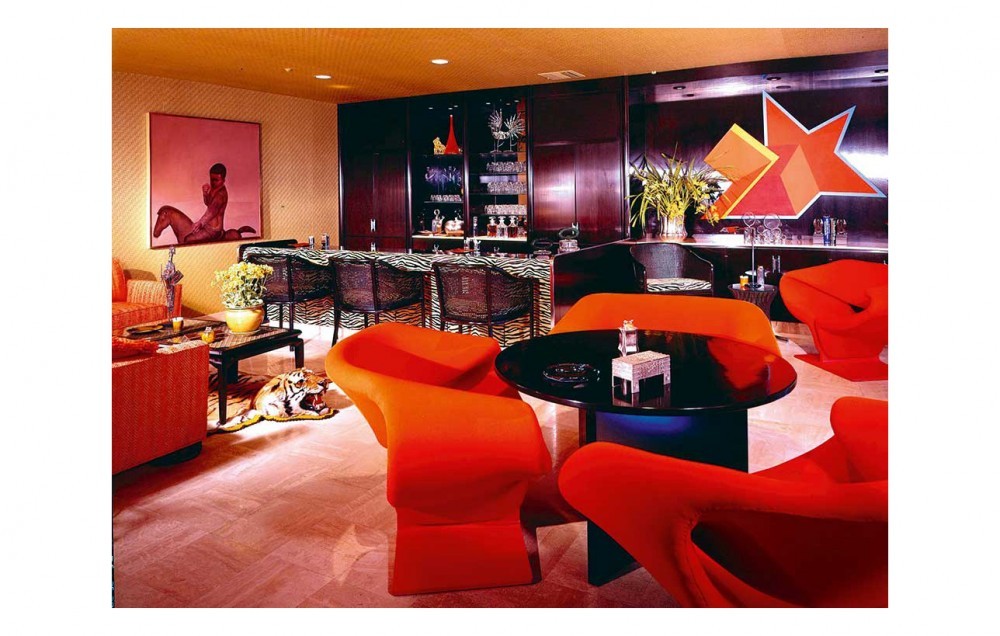

And so Elrod’s style transformed as demand continued to rise for his Palm Springs work, although he never gave up his overstatements. His most original interiors were not in the desert but the offices for the Johnson Publishing Company in Chicago. Another interesting example is in Bellevue, Idaho, a house that was designed for E. Hadley and Marion Stuart. Predominantly rendered in shades of gray, the ranch’s rooms were theatrically picked out in an electro-Victorian symphony of light pastels and dark organic hues — “crushed-raspberries-and-cream pinks, lime green, and deeper green,” as the Los Angeles Times described it when writing up the owners’ housewarming party. Indeed much of Elrod’s work was defined by a fusion of the traditional and the contemporary, until he surrendered to the streamlined vision exemplified by his namesake house — a style that eschewed pastiche and gaudiness in favor of the neat and the sharp. It is precisely this journey of decluttering, focusing and paring down that Cygelman’s book so elegantly recounts.

Text by Arshy Azizi