NOGUCHI’S MIDWESTERN MOONSCAPE: From Magic Chef To A U-Haul Center

In 1904, St. Louis, Missouri hosted the World’s Fair: an exhibition of architecture, culture, and technology; the debut site of the first wireless telephone, the dirigible, and the ice cream cone. However, the city that once was a hub for innovation and success eventually faded into the background in the 1950s. Despite being the eighth largest American city in 1950, St. Louis’s population and economy declined after large local companies were bought from out of state. By the late 1950s, St. Louis fell into the shadow of Chicago’s growing metropolis. In the context of architectural history, St. Louis is now often placed on the map for two quite opposite developments: Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch and Minoru Yamasaki’s infamous Pruitt-Igoe housing projects. The former a monument to American success and the latter a tale with an unsettling end. While the Modern architecture narrative often forces St. Louis into this dichotomy, the midwestern city houses other projects that are worth celebrating.

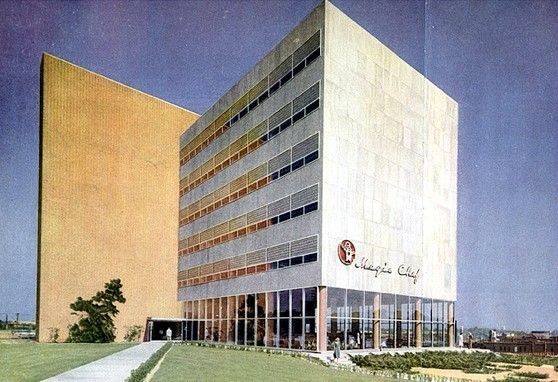

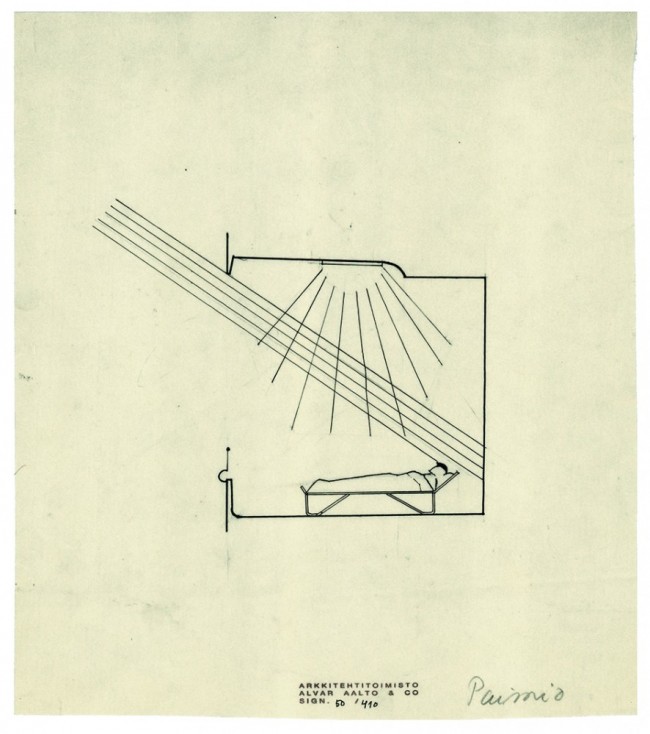

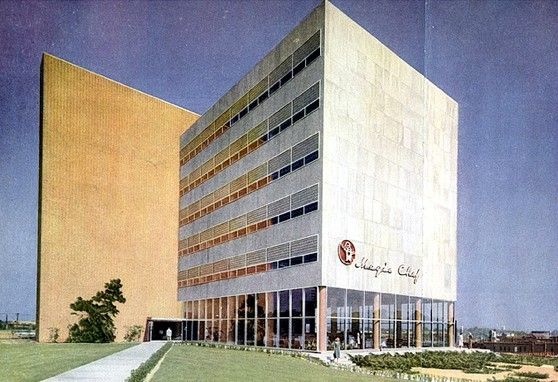

In 1946, local architect Harris Armstrong was commissioned to design the headquarters for St. Louis-based gas stove and kitchen appliance manufacturer Magic Chef (formerly the American Stove Company). The building was furnished by Armstrong and Charles Eames, but the Isamu Noguchi-designed ceiling steals the show. Reminiscent of the technology-obsessed era that produced Peter and Alison Smithson’s House of the Future (1956), Noguchi’s work is similarly molecular and undulant. The ceiling, consistent with Noguchi’s early sculptural pieces, is one of three “lunar landscapes” inspired by the artist’s experiences at a Japanese internment camp in 1942 Arizona. Despite the fact that this was more than two decades before man had ever set foot on the moon, Noguchi captured the futuristic yet lonely topography of a place untouched by man: a “moonscape of the mind.” The Magic Chef lunar landscape is the only lasting of the three, with both Noguchi’s ceiling in the Time & Life Building in New York and his interior wall of the SS Argentina Ocean Liner since removed.

Harris-Armstrong-designed headquarters for the Magic Chef Company in St. Louis, Missouri (1946). Courtesy of U-Haul.

Genny Cortinovis, Assistant Curator at the St. Louis Art Museum, notices a subtle trend in Armstrong’s interiors. The Noguchi in the Magic Chef headquarters arguably resembles Armstrong’s Shanley Building from 1935: a dentist office whose reception room ceiling was painted with a starry skyscape. While a nighttime scene might understandably calm an anxious patient’s nerves, some wonder what a Noguchi was doing in a kitchen appliance showroom, drawing shoppers’ eyes skyward rather than toward the products for sale. Strangely placed, yet oddly amusing. Was the Noguchi ceiling merely an item for the mid-century consumerist culture, no different from the superficial, ultra-Modern Villa Arpel? Or perhaps, was it something deeper? Armstrong seems to have possessed a restless mind, eager to see beyond his immediate environment. Maybe in Armstrong’s world, the Noguchi is representative of a yearning for adventure, juxtaposed with quotidian ovens for a midcentury housewife.

Dentist office reception room of Harris Armstrong's Shanley Building in St. Louis, Missouri with painted night sky ceiling (1935). Courtesy of the Harris Armstrong Collection, Julian Edison Department of Special Collections, Washington University in St. Louis and the Saint Louis Art Museum.

Magic Chef left the Armstrong building after the gas stove industry was replaced by electric. The site was vacant for a decade until American moving and storage company U-Haul took over and eventually hid Noguchi’s work with a drop ceiling in the 1990s. Though Noguchi couldn’t have seen this coming, maybe his imagination for the future warned him that his moonscape would find itself in a lonelier, colder darkness. In 1987, 40 years after the Armstrong building opened, Professor M.B. McNamee of Saint Louis University requested that Noguchi donate a sculpture to the school’s campus, only for Noguchi to respectfully decline. Sure, Noguchi’s heart was set on designing works for other sites, but maybe he had a feeling that his earlier commission for the city would not be appreciated to his liking.

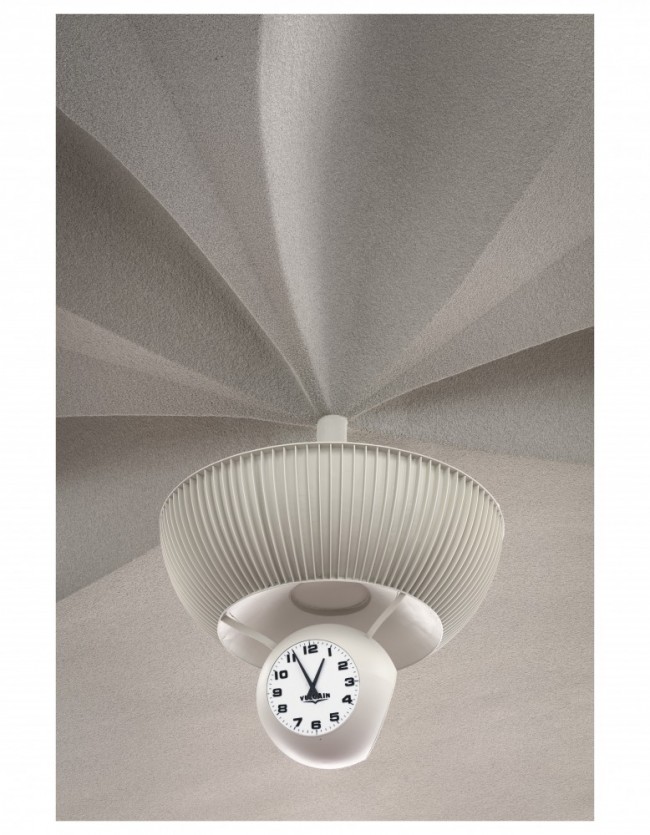

Noguchi-designed ceiling panel in the St. Louis U-Haul building. Image courtesy of the author.

Through the years, Noguchi’s lonely landscape was caught by the eyes of only those who knew to lift the ceiling panels, peeking at it in fragmented sections. Finally, in 2016, the year following the 50th anniversary of the Gateway Arch Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (for which both Noguchi and Armstrong also submitted designs) and a mid-century Modern design exhibition at the Saint Louis Art Museum (co-curated by Cortinovis), Noguchi’s sculpted ceiling was made visible to the public eye once again, visited by St. Louisans with a piqued interest in their city’s past. Repainted and fitted with new lighting, the landscape now acts as a backdrop for shipping boxes and storage unit plans.

Noguchi-designed ceiling panel in the St. Louis U-Haul building. Image courtesy of the author.

St. Louis is making an urban comeback, with efforts popping up around the city to preserve and protect its mid-20th century Modern attractions. The Noguchi is seen again, both by those who seek it out and by those who stumble across it while preparing to move homes. A gentle reminder of glory days that once were, and the glory days to come. Or at the very least, a bit of surprise among the mundane tasks of daily life.

Text by Karina Encarnación.

Special thanks to Genny Cortinovis, Assistant Curator of Decorative Arts and Design at the Saint Louis Art Museum.

Images courtesy of the Saint Louis Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, U-Haul, and the author.