Arno Brandlhuber’s Concrete Retreat in Rocha, Uruguay

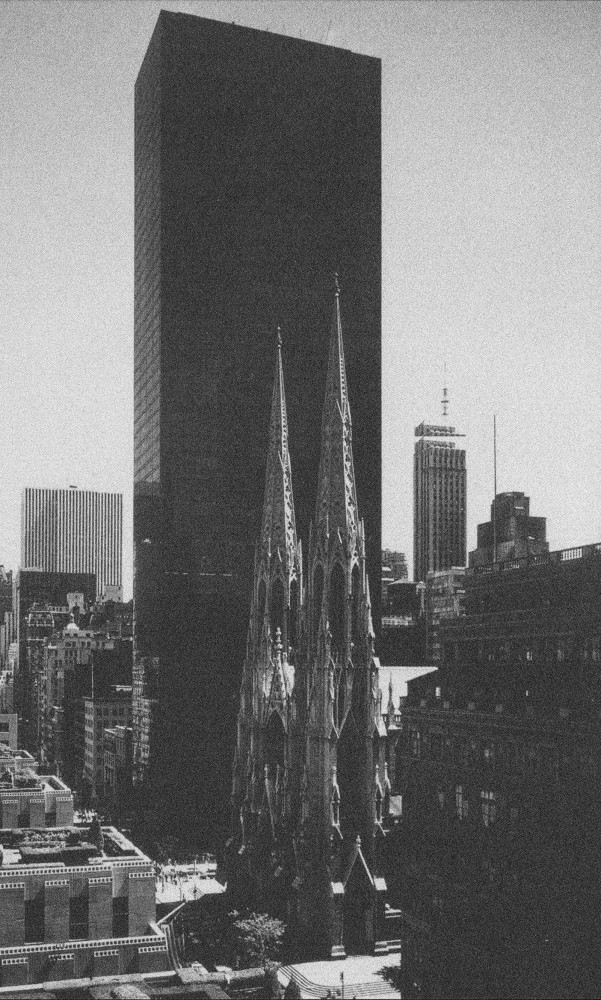

At its best, Modernist architecture attempted to materialize a progressive vision for contemporary life. But often the very people whose lives Modernism sought to improve were the first to resent having a new set of values imposed on them. It is no doubt an oversimplification of Modernism’s ambitions and attendant shortcomings, but it’s a useful starting point for understanding the work of architect Arno Brandlhuber of Berlin-based office Brandlhuber+. If Modern architecture’s apparent failure to garner mass appeal can, at least in part, be attributed to its perceived austerity and lack of charm, Brandlhuber’s response is to introduce a bit of hedonism into the mix.

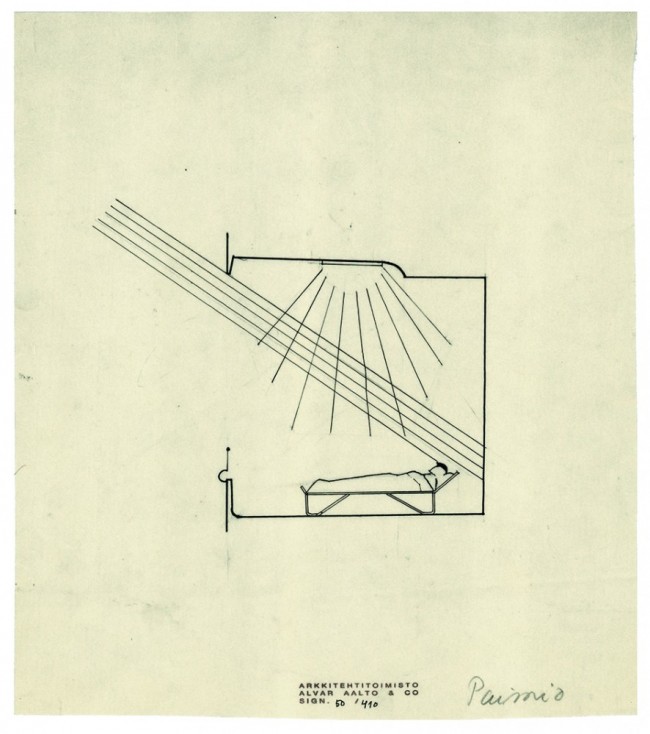

The house’s stacked interior levels maximize daylight for specific uses: sleeping and secondary rooms are oriented east-west, while more active areas are oriented north-south. The ground floor below is simultaneously aligned with all directions.

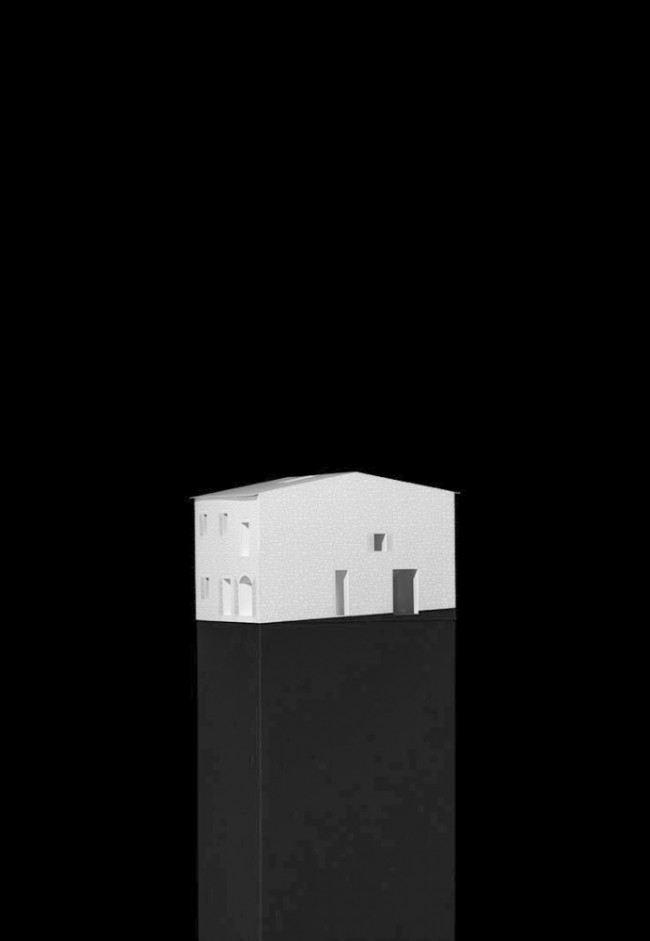

Nowhere is this ethos more apparent than in the architect’s design for a house near Rocha, a small town an hour north of Uruguay’s holiday hotspot Punta del Este. Completed in 2015, the three-story building is the first built example of Vier Richtungs Module (“four-directions module”), a live-work typology that Brandlhuber’s studio has been developing for over a decade. The typology is based on a combination of maisonette units whose first and second levels are disposed perpendicularly to one another, the idea being that an east–west orientation is ideal for living — morning and evening sun — while northern exposure (in the northern hemisphere that is) is preferable for working. Economical to construct, the module comes endowed with “built-in” luxuries: windows that face in all four cardinal directions, a double-height space, and an exterior entrance for each unit. The typology is motivated by a belief that architecture can empower its users, and is currently being proposed for stacked refugee housing in Hamburg, Germany, so that occupants are provided both with shelter and a space to set up a small business.

The rounded corners of the bathroom doors are Brandlhuber's nod to the interiors of Charlotte Perriand's 1970s ski resort Arc 1800. Built with unfinished plywood, the bathrooms run between the housing modules, such that each can also be accessed from the neighboring unit.

A vacation home on a sandy stretch of the Uruguayan coast might not seem the most obvious location to test a mass-housing typology designed to facilitate alternative domestic models, but it does serve as a case study for the scheme’s adaptability. Approached by German clients who run a youth services organization, Brandlhuber was asked for a building that could host one of their travel programs in the summer but also be subdivided into smaller apartments to be rented out individually the rest of the year. Perched up on pilotis above a pool, six 12-by-40-foot modules are stacked Jenga style and paired off into three two-floor units, each of which can function independently or be combined with the others to form a single villa. Collectively the units strike a balance between the desire to minimize redundancy and the requirements for self-sufficiency: one has a relatively large kitchen, one just has a couple of burners, while the third only has an outdoor grill. They all start from the same basic spatial condition, but each unit is designed to be used in different ways. The house fits the specifications of the project brief, but also suggests other opportunities, such as the possibility of hosting a visiting friend in one unit, or temporarily downsizing and renting out the other units when short on cash.

The lush dunes, mild climate and sparse population of Rocha, Uruguay’s easternmost province, offers a chill antidote to the 24/7 hedonism of nearby Punta del Este.

Overlooking the ocean from its beachside pine-grove location, the house is constructed from a concrete frame with brick infill, a method that local workers are familiar with and could realize cheaply. The materials are left raw, expressing a straightforward philosophy: concrete is concrete, wood is wood (the bathrooms, cabinets, and furniture are constructed from plywood and were built by German woodworkers who spent two months working onsite). Heating is provided by fireplaces, and curtains can be used to partition the open floor plan. The details are typically blunt, like the floor-to-ceiling mesh installed in place of handrails. “It shouldn’t look like the quality is coming out of detailing,” argues Brandlhuber. “Architects should spend their time on other things!”

Brandlhuber likes to describe his projects using words like "cheapness" and "luxury" in the same sentence, reconciling some of Modernism’s core tenets without compromising comfort and pleasure.

And it is from these “other things” that the house derives its energy. Customary appointments and amenities are sacrificed in exchange for an open-ended design that functions as an adaptable resource for its occupants. It’s an alternative conception of luxury, based on an egalitarian vision for society. “One of the biggest luxuries is to have a cheap home!” says Brandlhuber. “It allows for flexibility in your lifestyle and accommodates changing situations. But there should be basic qualities. It should be something you can celebrate — cheap but glorious!”