In Search of a New Spatial Contract at the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale

How will we live together? Following a year of industry hand-wringing and Zoom roundtables about adapting cities for social distancing, the pandemic-era irony of the curator Hashim Sarkis’s central question seemed refreshingly distant at the in-person opening of the 17th Biennale di Architettura in Venice. Save the mandatory masks and paucity of parties for the young architecture crowd, it was back to regularly scheduled programming, grasping for design solutions to longstanding crises like climate change, mass migration, and systematic inequality.

In his manifesto and in interviews, Sarkis, Dean of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning, made one thing clear: politics is not the answer. Instead, to figure out how we should live together, designers need to embrace their power “to propose a path towards a better future,” defining a new spatial — as opposed to social — contract. In a year when politicians seemingly failed humanity while doctors and scientists saved us, the call to bypass politics and listen to the experts has a seductive, pandemic-era ring.

-

Resurrection of the Sublime (2019), an immersive installation by Christina Agapakis, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, and Sissel Tolaas, allows visitors to smell extinct flowers lost due to colonial activity.

-

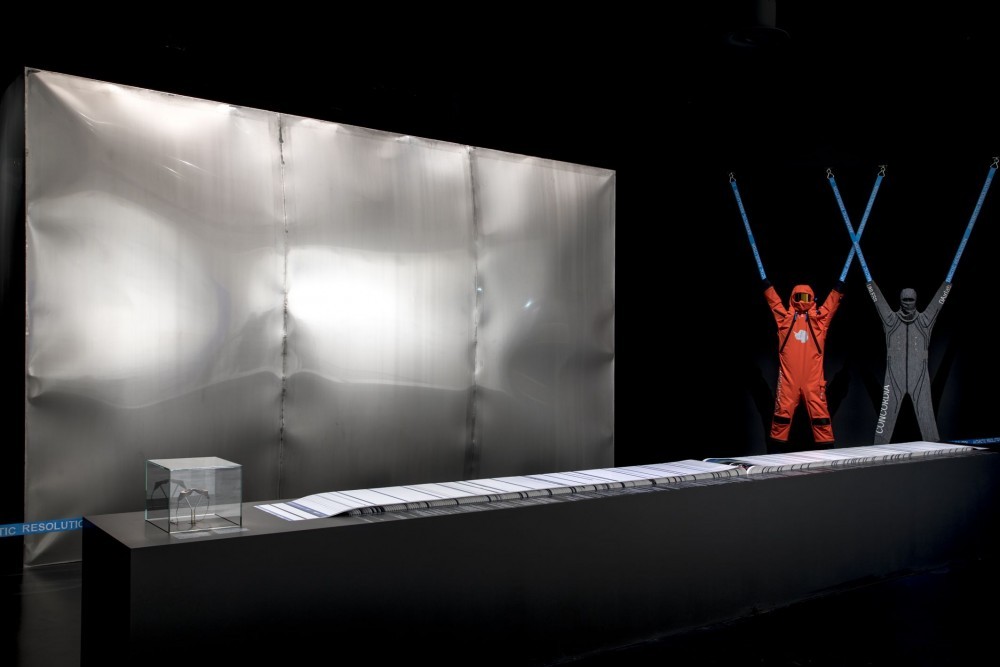

Antarctic Resolution (2021) by Giulia Foscari / UNLESS in collaboration with Arcangelo Sassolino, D-Air Lab, and The Scott Polar Research Institute.

-

An experiment in structural stone vaulting by AAU Anastas Studio from Bethlehem, Palestine.

-

Museo Aero Solar For an Aerocene Era (2007) is a collective project initiated by artist Tomás Saraceno. The installation at the Venice Architecture Biennale consists of an inflatable balloon made out of reused plastic bags cut, pasted, and joined together. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

-

Timber structure in the Arsenale for the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale. The construction was conceived by Elemental, led by Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena.

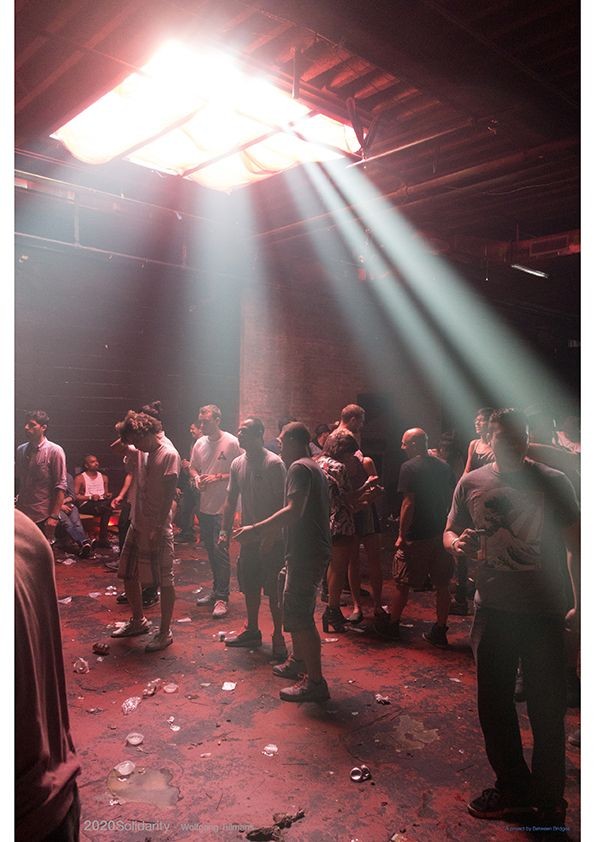

The sprawling main exhibition is organized along five scales from the bodily (Among Diverse Beings) to the planetary (As One Planet). While the Arsenale’s cavernous Corderie will often drag on endlessly, Sarkis’s fertile main question and clear curatorial structure help whisk visitors along a succession of interactive environments, climbable structures, and even hospital beds to lounge on. What the main exhibition — and the Biennale at large — lacks in the way of specific architectural proposals, it compensates with sensory experiences and conceptual conceits. You can hear a sound simulation of icebergs cracking, step inside a hot air balloon made of recycled plastic bags, smell extinct flowers, and see a 3-D data sculpture based on MRI scans. If dry design exhibitions sometimes feel akin to the dusty curios of a 19th-century academy, elements of the current mishmash in Venice would seem at home in a well-executed science museum for children. While addressing tough topics, many contributions favored the whimsical over the polemical, the poetic over the concrete. Remember: technology not politics.

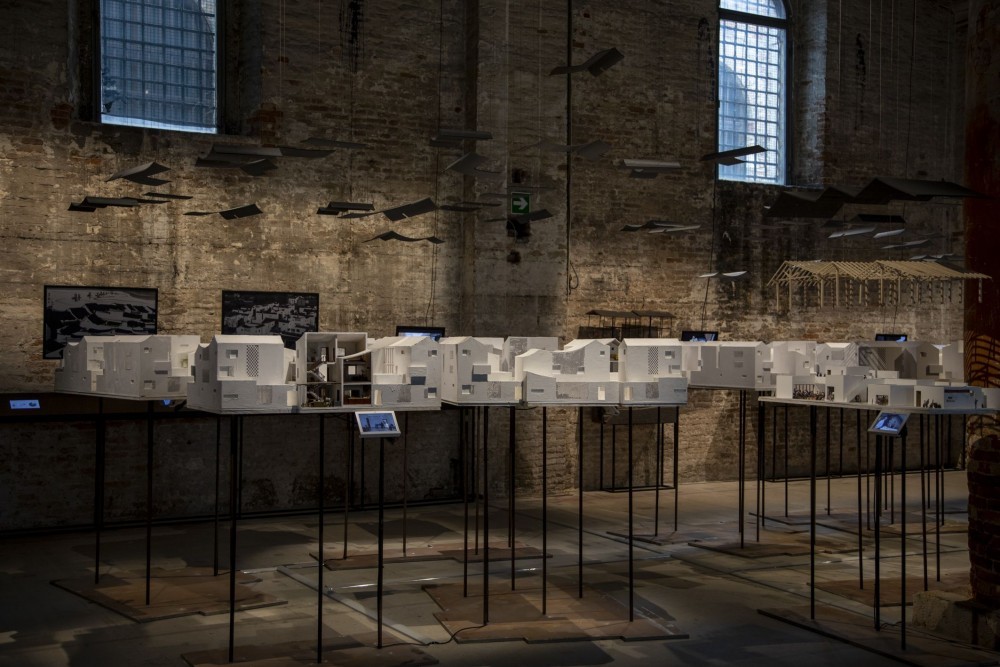

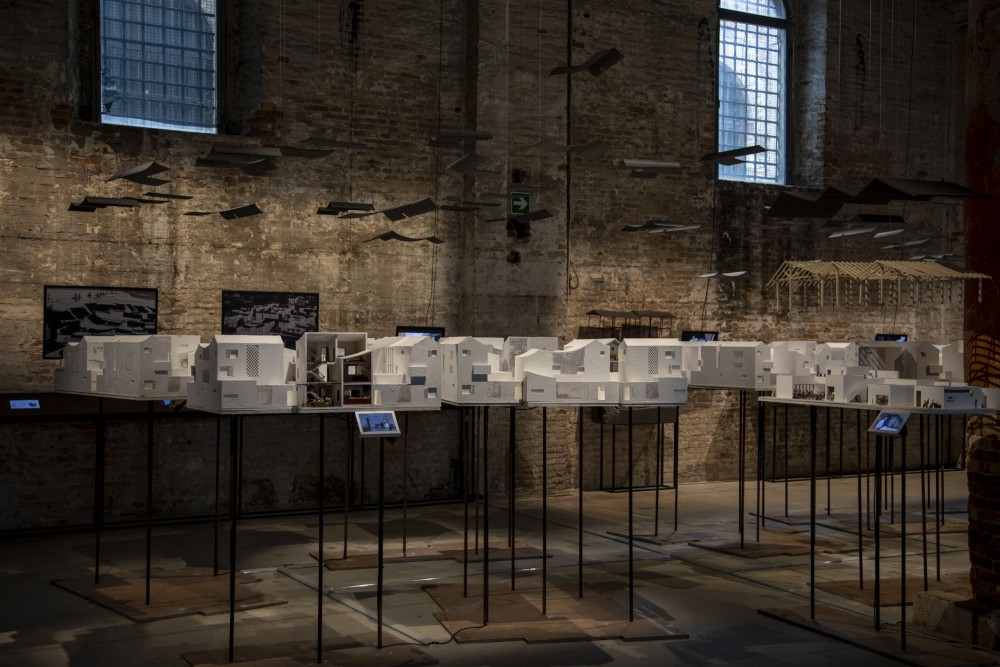

Physical model of Dongziguan project line+ studio Rural Nostalgia | Urban Dream (2018) by Line+.

One triumph of this year’s Biennale is the range of its contributors. Light on big firms and starchitect-y ego, the main exhibition draws together a geographically and ethnically diverse pool of smaller-scale firms and research teams. A section on co-housing features realized structures like a self-managed housing project in Barcelona (La Borda by Lacol Arquitectura) and a housing complex for relocalized farmers in Hangzhou (by Line+’s Meng Fanghao and Zhu Peidong) where winding streets between houses acts as programmable community space. Moments like these feel less flashy and more useful, illustrating how Sarkis’s vision for a new spatial contract might look if we learn to live together differently.

Addition to the Pavilion of the United States at the 17th International Architecture Exhibition at La Biennale di Venezia. Photography by Co-Curators Paul Andersen and Paul Preissner.

In the Giardini, a similar principle held across the main and national pavilions this year: the farther away a contribution drifted from the building scale, the more gestural or flimsy it felt. The U.S. Pavilion, a popular standout, forgoes theory and new technology altogether, focusing on the underappreciated construction method behind 90 percent of American homes: wood-framing. The curators — Paul Andersen and Paul Preissner — erected a four-story timber structure in front of the neo-classical pavilion to showcase this most democratic of architectural forms. In contrast to some of the speculative gobbledygook made by architects moonlighting as installation artists and media theorists, the boards-and-nails approach felt robust and almost radical in its simplicity and accessibility.

-

Interview of the 2038 THE NEW SERENITY, Germany’s contribution to the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale. The pavilion is curated by Arno Brandlhuber, Olaf Grawert, Nikolaus Hirsch, and Christopher Roth and relied on QR codes to link to the project’ ambitious interactive website.

While the pandemic itself was only lightly addressed in this year’s Biennale, the yearlong delay did push many countries to reconsider how they engage with a privileged audience in Venice versus a potentially global audience online. Russia, for example, largely went digital with exhibition content, but took the opportunity to renovate its century-old pavilion. Whether to view these forays into internet-first curation as a feat or an excuse depends on whom you ask. Eschewing the usual “phygital” compromise, Canada and Germany controversially turned to the QR code. While the shuttered Canadian pavilion was draped in a glorified green-screen that came to life through an Instagram filter, the German Pavilion — an intellectually fun dispatch from a post-climate-crisis future in 2038 — was, in person, empty white walls and small QR shortcuts that dreadfully recall filling out Covid tracing forms or loading digital restaurant menus. Call it Zoom fatigue if you want, but after a year of staring at a screen, it’s easy to yearn for something more visceral.

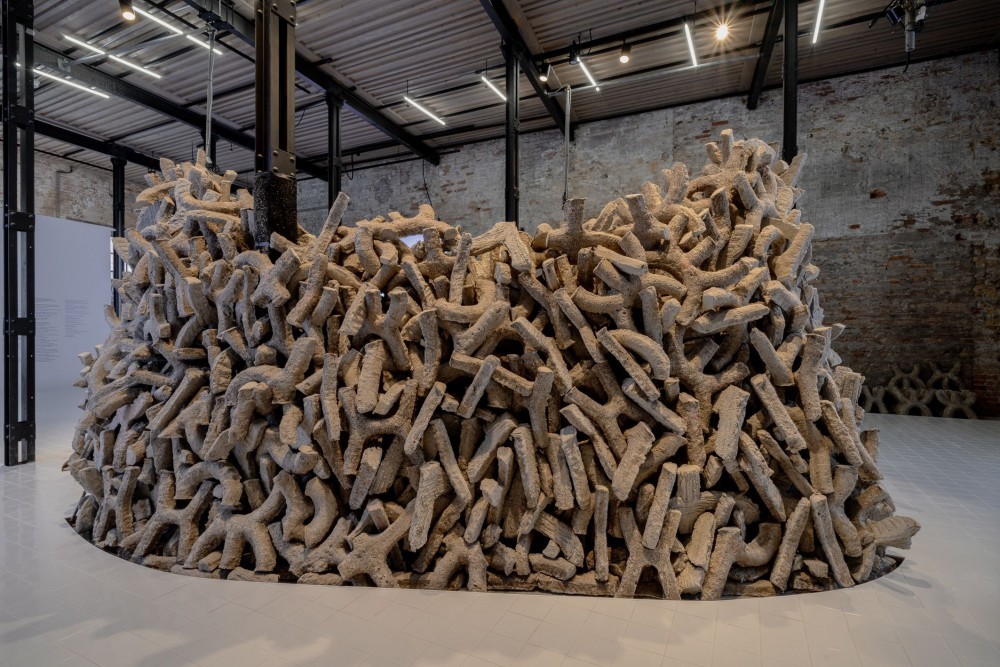

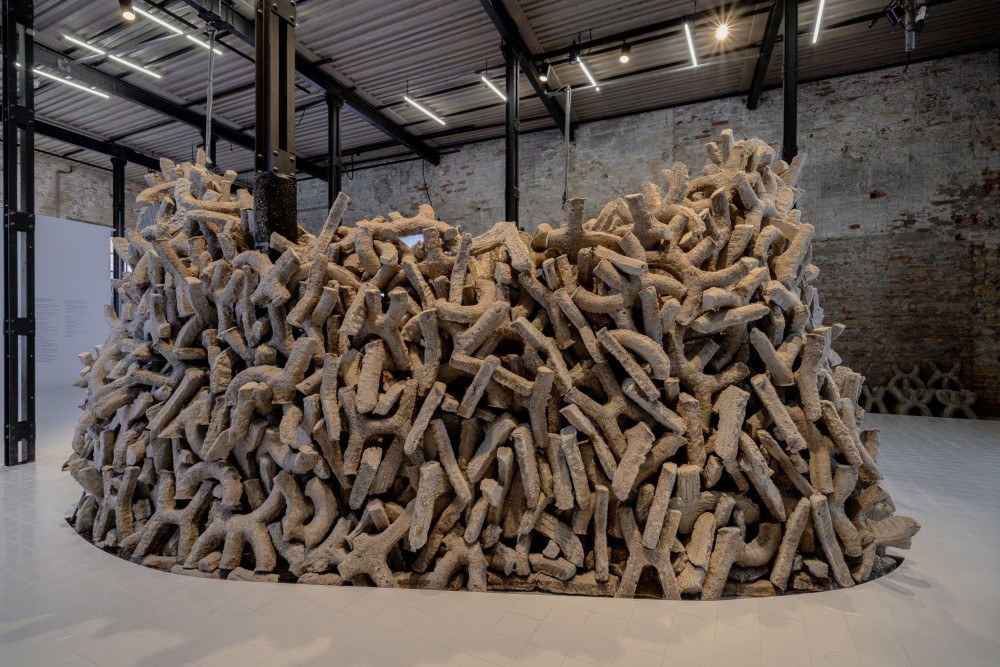

Wetlands, an installation about saline bricks in the shape of corals. Curated by Wael al Awar and Kenichi Teramoto for the Pavilion of the United Arab Emirates at the 2021 International Architecture Exhibition.

The United Arab Emirates, one of the strongest national pavilions, offers precisely that with Wetlands, honing in on one extremely visceral quality of architecture: its materiality. Looking for alternatives to the ubiquitous Portland cement (which accounts for 8 percent of global CO2 emissions), curators Wael Al Awar and Kenichi Teramoto drew inspiration from the naturally occurring salt flats around Abu Dhabi to develop a substitute for concrete. While years from being ready for market, the process converts salt brine residue — a waste product from UAE’s desalination plants — into a new material vernacular tied to the environmental site-specificity of the Gulf kingdom.

-

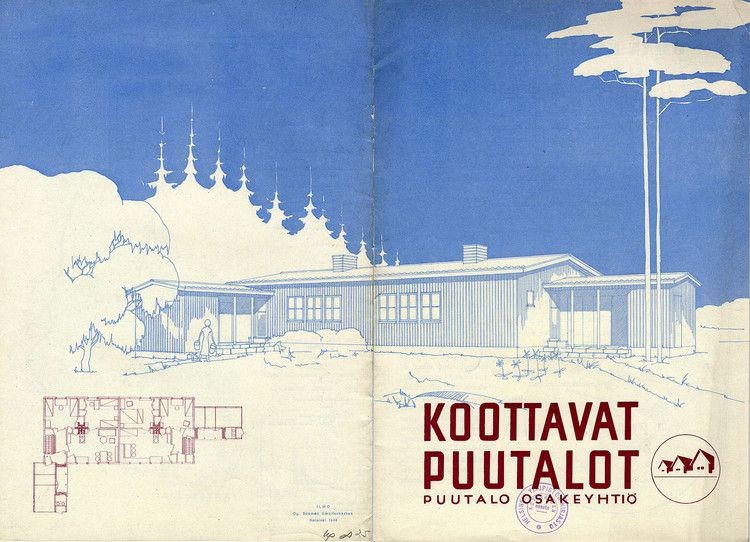

A brochure promotes the Puutalo company in its founding year 1940. The text advertises model homes that can be “erected from parts in a matter of days” and the cover depicts a modified version of the Rauhakoto (Peace Home) type house which has been configured for two families with separate saunas and washrooms. Image © ELKA for the Finnish pavilion at the 2021 Biennale di Venezia

-

New Standards, an exhibition by Kristo Vesikansa, Laura Berger, and Philip Tidwell for the Finnish pavilion. The exhibition retells the history of Finnish manufacturer Puutalo Oy who developed a popular prefabricated timber house for the influx of over 400,000 Karelian refugees expelled from the Soviet Union after WWII.

-

Interior of the Japan Pavilion at the 2021 Biennale d'Artchitettura di Venezia. Curated by Kadowaki Kozo, the pavilion retells the story of one wooden Japanese hosue. Photography by Alberto Strada

Wood is a major reoccurring theme. In the Alvar Aalto-designed Finnish Pavilion, Kristo Vesikansa, Laura Berger, and Philip Tidwell retell the history of Finnish manufacturer Puutalo Oy who developed a popular prefabricated timber house for the influx of over 400,000 Karelian refugees expelled from the Soviet Union after WWII. The well-built, cheap model was so successful it was subsequently exported back to the Soviet Union, and around the world. Japanese curator Kadowaki Kozo successfully creates one of the most touching moments of Biennale by retelling the personal history of one wooden house, disassembled and shipped to Venice, its beams lain across the pavilion floor. In a clever ode to the sustainable afterlife of building materials, Italian craftsmen have produced new furniture pieces out of the scraps of the former occupant’s domestic life. Excellent historical photography across both pavilions, much like Daniel Shea and Chris Strong’s contemporary images for American Framing, deepen the cross-pavilion observation that traced in the grains of one of the simplest building materials — wood — is a rich social history of living and building together.

-

A. I. Toys Shapes and Ladders: Battles of Bias and Bureaucracy Maternity Menswear (2020), by Ani Liu.

-

Installation Your Restroom is a Battleground (2021) by Matilde Cassani, Ignacio G. Galán, Ivan L. Munuera, and Joel Sanders.

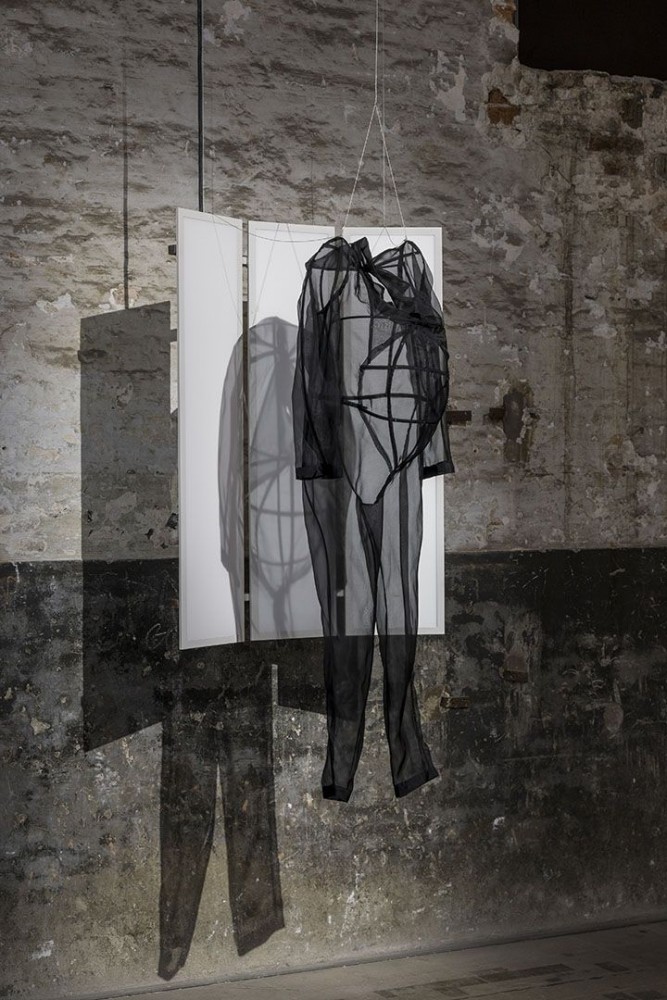

If, as Sarkis argues, architects should propose a new spatial contract that “precedes, rehearses, articulates, (and) materializes” any social contract, architecture must take into account historically marginalized peoples and bodies. The opening rooms of the Arsenale, Among Diverse Beings, feature provocative installations that draw attention to the way design professions have engaged in exclusionary biopolitics — such as Ani Liu’s “maternity menswear” or MIT Future Heritage Lab’s “body-scale construction site” featuring mannequins representing people marginalized by their Islamic identity coming together to build “an inclusive, pluralistic society.” Nearby, Your Restroom is a Battleground makes the obvious but needed point that spatial design choices made for utilitarian infrastructures like public toilets reflect dominant ideologies about gender, race, and class. Another highlight is the V&A’s special contribution Three British Mosques in the Arsenale’s Applied Arts Pavilion. Featuring life-size reconstructions of architectural elements from three ad-hoc Mosques in London, architect and writer Shahed Saleem documents how adapted, marginal spaces can flourish as anchors of cosmopolitan identity.

-

V&A’s special contribution Three British Mosques in the Arsenale’s Applied Arts Pavilion, curated by Shahed Saleem of Makespace.

-

Future Assembly is a collective exhibition within the Venice Architecture Biennale, a collaboration between Studio Other Spaces and six co-designers.

These human-scale narratives stand in contrast to many of the technofuturist, planetary-scale proposals and QR-accessed content clouds elsewhere in the Biennale that position architects to not only solve spatial problems, but to lead new governance structures and manage future social relations. While the industry’s love of technology and distrust of politics may make economic sense in a competitive market, it can betray who is considered the “we” that must live together in the future. When Sarkis optimistically posits that “a spatial contract could constitute a (new) social contract”, we must not forget that in reality it primarily goes the other way round: the structure of our cities and the quality of our homes is heavily determined by power relations. The engineering behind Venice’s new inflatable flood barriers is one thing, the decades-long political fight to get it done was another. Some of the most powerful moments of the Biennale show designers engaging actively in politics, such as Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal’s film about their collective Decolonizing Architecture Art Research’s attempt to landmark the Dheisheh refugee camp in the Palestinian West Bank. As Israeli bombs fell on civilians in Gaza over the past few weeks, the architecture world was reminded again: you can’t design your way out of politics, or apartheid.

Text by Andrew Pasquier

Images courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.