Koolhaas’s Countryside Show Spirals At The Guggenheim

Wake up, urbanites! There’s a big world out there and Rem Koolhaas is here to enlighten you for the price of admission to the Guggenheim. In the recently opened exhibition Countryside, The Future you can find something for everyone: tractors, gorillas, smartphone apps, Nazi ideology, refugees, and recordings of Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” in a dozen languages. Koolhaas and his disciples scoured the far reaches of the globe to put together this slurry of facts, pithy observations, and farm-adjacent ephemera in order to convince you that “the countryside” does, in fact, matter.

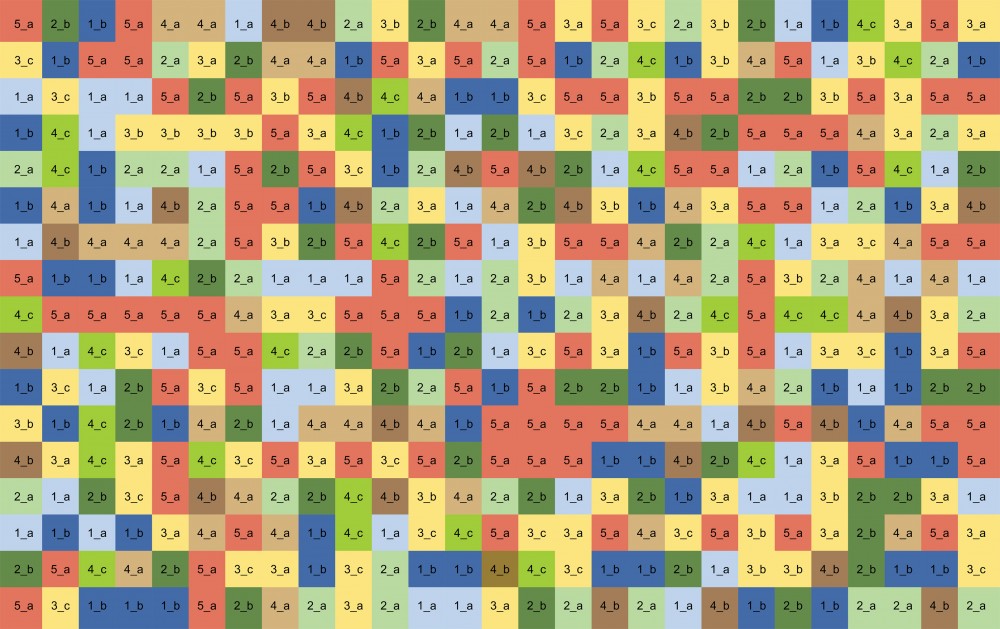

What do permafrost, Mao’s Great Leap Forward and hippie communes have in common? Not much, we learn, save Koolhaas’s observation that they occur in the “98% of the Earth’s surface that is not urban.” (That’s how “the countryside” is defined although the exhibition acknowledges it’s “a glaringly inadequate term.”) Spiraling between ideologies, continents, and millennia, some of the exhibition’s deep-dives feel concocted by grad students on Wikipedia and Adderall, while other sections feel timely, educating visitors about China’s Belt-and-Road Initiative or pixel farming and high-tech greenhouses that are displacing traditional agriculture. A playful assortment of pastoral references — a photograph of a cow, a cut-out from Millet’s The Gleaners — pasted around the rotunda floor reinforce the notion that the show’s curation owes more to unbridled childhood curiosity than focused critical perspective — a schizophrenic attempt at rural rediscovery in atonement for Rem’s (and our own) myopic urban worldview.

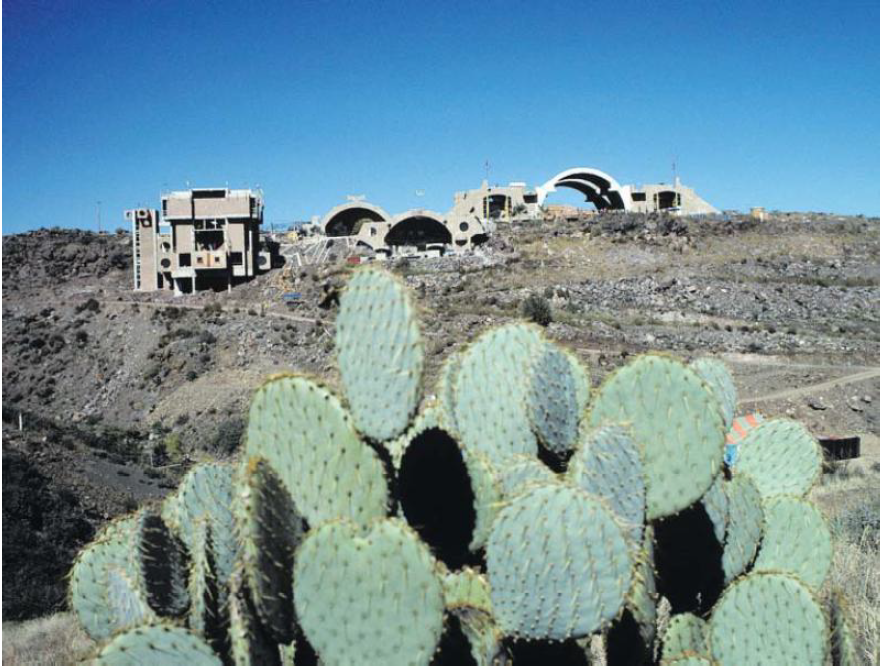

-

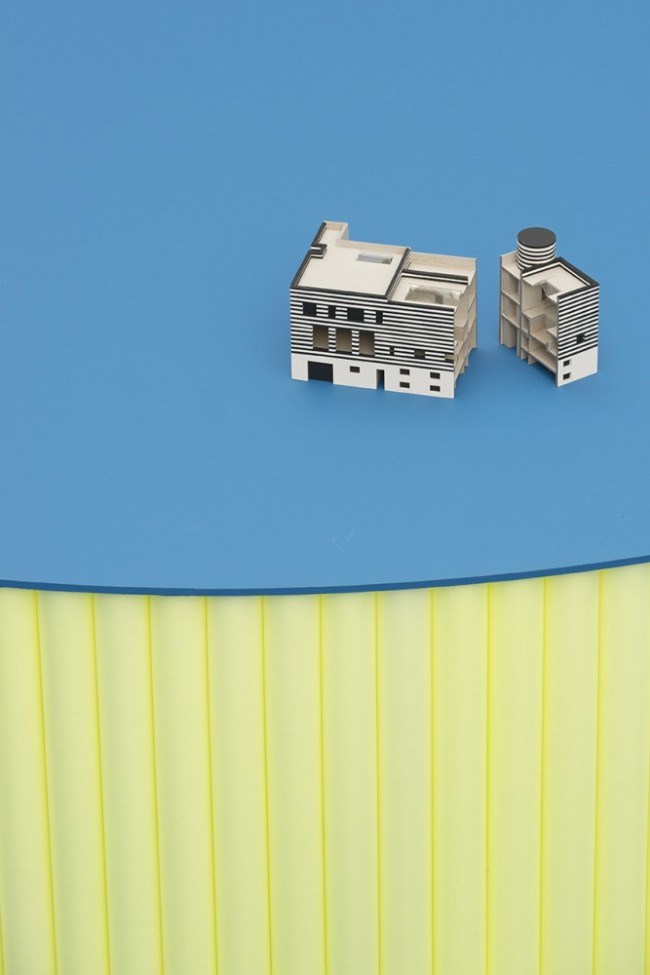

Installation View of Countryside, The Future, on view at the Guggenheim until August 14, 2020. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

-

Rem Koolhaas; Troy Conrad Therrien, Curator of Architecture and Digital Initiatives, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; Samir Bantal, Director of AMO. Photography by Kristopher McKay. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2019

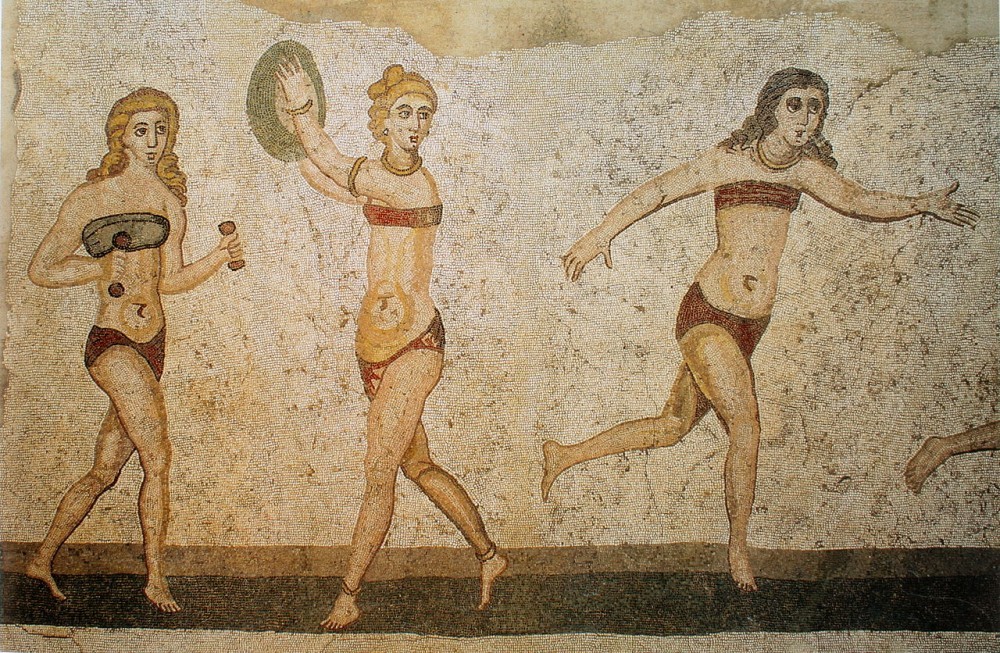

-

Installation View of Countryside, The Future, on view at the Guggenheim February 20 until August 14, 2020. Image by Laurian Ghinitoiu. Courtesy AMO

So in a show whose subject is the vast majority of Earth, how was it decided which rural narratives would make the cut? An extensive network of graduate students and experts collaborated with Koolhaas, Samir Bantal (leader of AMO, the research arm of OMA), and Troy Conrad Therrien (the Guggenheim’s curator for Architecture and Digital Initiatives) over several years to produce what you see in the Guggenheim’s “pointillist” portrait of the countryside. In an aptly named accompanying essay, “Along for the Ride,” Therrien admits that the featured topics “could seem random to a casual visitor” but while “intuition often drives, nothing is accidental.” When I ask him to explain the team’s decision-making process over email, it becomes clear whose intuition he meant. Viewing his most consequential role as curator as “simply holding space for Rem’s intuition to play out,” Therrien expressed to me how he “started to feel (Rem) has a preternatural sense for where things are going in culture — a read on history in the making.” Framing the exhibit around Koohaas’s celebrity wasn’t just a PR move — the Guggenheim really did give carte blanche to the intellectual whimsies of one man.

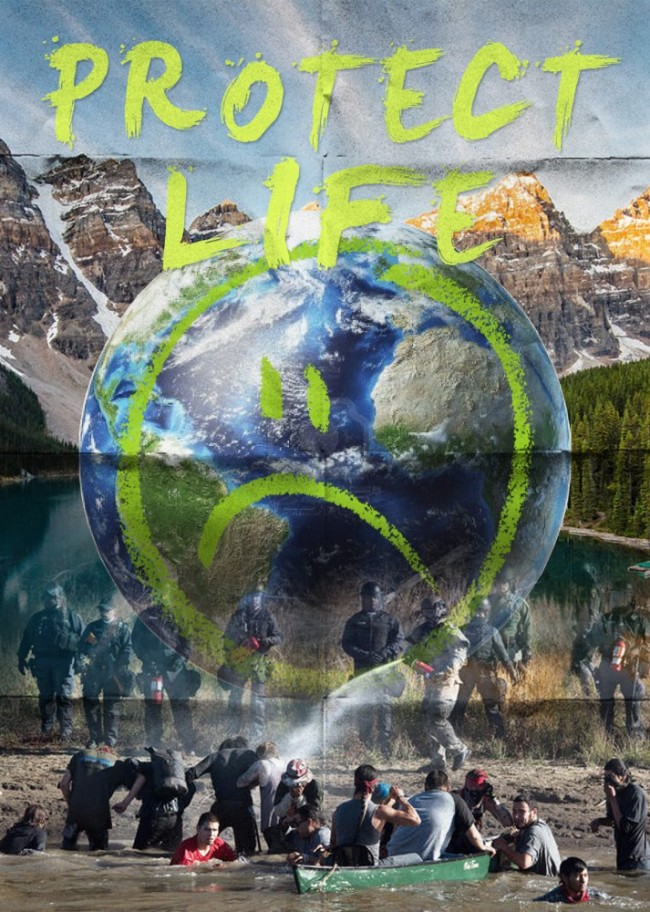

Installation view of an image by Laurian Ghinitoiu included in Countryside, The Future. Courtesy AMO

The show strikes me a bit like Koolhaas’s version of Thoreau’s Walden: a performative exercise in understanding the countryside that is rife with irony and feelings of self-importance. Koolhaas went to the woods (and many other biomes) to discover both the meanness and the sublime of the global countryside in order to reduce it to its lower terms on the walls of the Guggenheim for us simple-minded metropolitan folk. Yet as Koolhaas cut a broad swath and shaved close in search of the most “demonstrative, predictive, and hyperbolic” narratives to share with us, he seems to undervalue learning from the true experts of the countryside: those who live there. This oversight leads to bizarre statements: “now claimed by conservative news pundits, billionaire survivalists, and fulfillment centers, the American countryside was once the preferred stage of radical utopian visions, a perch from which the self-determined could wage war on the city.” In fact, the vast majority of people who live in the American countryside do so not because of some ideological complex, but on account of simple sociological factors like economic opportunity and family ties. Indigenous communities — timeless stewards of the non-urban — also somehow are passed over amid Koolhaas’s curatorial pointillism.

Still, in both its scope and ambition, Countryside, The Future is far more inspiring and provocative than whatever artist retrospective would normally grace the curved walls of Frank Lloyd Wright’s six-story rotunda. Here is a place to nerd-out and ask big questions. As the mass of humanity has rushed towards cities over the last century, what are the implications for the depopulated, devalued countryside? Furthermore, as the show vociferously argues, rural transformations occurring out-of-view today also offer instructive flashes about what’s to come for us cityfolk too. You may not live in the countryside, but tune in: this is the future.

Installation View of Countryside, The Future, February 20–August 14, 2020. Image by Laurian Ghinitoiu. Courtesy AMO

As a young journalist, Koolhaas recalls a mentor teaching him to “approach every situation like a Martian, completely foreign and amazed, and write it all down deadpan.” Applying this strategy to his five-year romp around the countryside after ignoring it most of his life, Koolhaas plays classic idiot savant. Able to beam down from spaceship Guggenheim across time and space, the strengths and weaknesses of the Martian approach become apparent as the curators tease out uncommon historical threads. Did you know that Ancient Rome and Ancient China developed parallel philosophical concepts celebrating rural leisure? Or how 2011 NATO bombings disrupted the largest irrigation project in the world, Muammar al-Gaddafi’s Great Man-Made River piping water from fossil aquifers in the Libyan dessert?

When I ask Therrien what he thinks about Koolhaas’ Martian approach, he references his own personal attempts “go beyond the comfort zones of urbanity, beyond the mentality of modernity, beyond engineering and “solutions.” Cryptically, he adds, “Decolonization isn’t complete without the re-enchantment of colonial minds.” Yet Koolhaas & Co’s survey of the global countryside is by metropolitans, for metropolitans and surprisingly full of metropolitan voices. Here is a celebration of the planned more than the organic. Lest we forget, colonizers and architects often share a fetish for the Cartesian ordering of nature.

-

Night view of greenhouses in the Westland area of the Netherlands, just south of the capital The Hague. Photography by Luca Locatelli. Courtesy AMO.

-

Pixel Farming Diagram. Image courtesy AMO

-

Off Grid Slab City, Salvation Mountain. Courtesy Annie Schneider.

Yet while the tools of planning often mirror tools of control, the show’s space-age-like reverence in the capacity of man to bend nature to his will does offer up an ingredient often lacking in contemporary discourse about climate change: hope. On the same floor of the museum as wall-mounts depicting melting permafrost is a section introducing two competing models for global conservation debated at this year’s UN Convention on Biological Diversity. If we are going to survive the current environmental crisis, how much and in what ways must nature be “preserved?” Sure, living through the Anthropocene is scary, but while acknowledging our power to fuck up the countryside we should also acknowledge our power to save it.

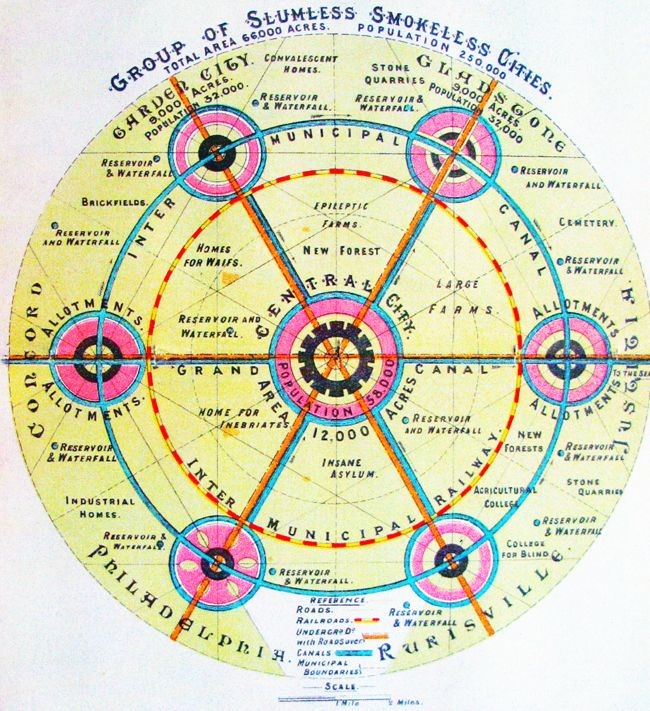

In one of the most informative sections called “Political Redesign,” despots and democrats are compared side-by-side. We learn about Roosevelt’s Dust-bowl-era “Shelterbelt Program” to plant trees around lot lines to fight erosion; Stalin’s mighty (but failed) plans to reverse the flow of Siberian rivers for irrigation; and Mao’s disastrous Great Leap Forward. Such blunt parallelism reinforces the obvious point that powerful men of all stripes dream up plans to exploit their hinterlands, but visitors are left wanting for ideological context. At the press opening on February 19, 2020, a particularly tenacious journalist laid in on Koolhaas — had the show adequately addressed threats like populism, corporate interests, and climate change? I was reminded of a recent investigative series in the New York Times exposing how farm subsidies — by far the largest line item in the European Union budget — were fueling the rise of far-right parties. Brushing off the journalist’s concern, Koolhaas argued that this is a show of “potential promising potentials” — the answers are “for the viewer to assemble.” As a neutral observer from a metropolitan Mars, Koolhaas offers no politics for the countryside.

This press conference jab was far from the show’s only criticism. The vitriol that Countryside, The Future has evoked from the criticize-everything-industrial-complex is not helped by Koolhaas’ irksome self-assurance. But strong reactions also speak to the show’s relevance. In it we are forced to confront messy realities that don’t fit neatly in the politically correct universe of a metropolitan art institution. Visitors are warned: “This is not an art show. This is not an architecture show.” Instead, Therrien argues that “the exhibition presents many places to stick a well-engineered lever to move the Earth in the right direction no matter where you come from. It offers a series of starter stories to break the spells that divide us.”

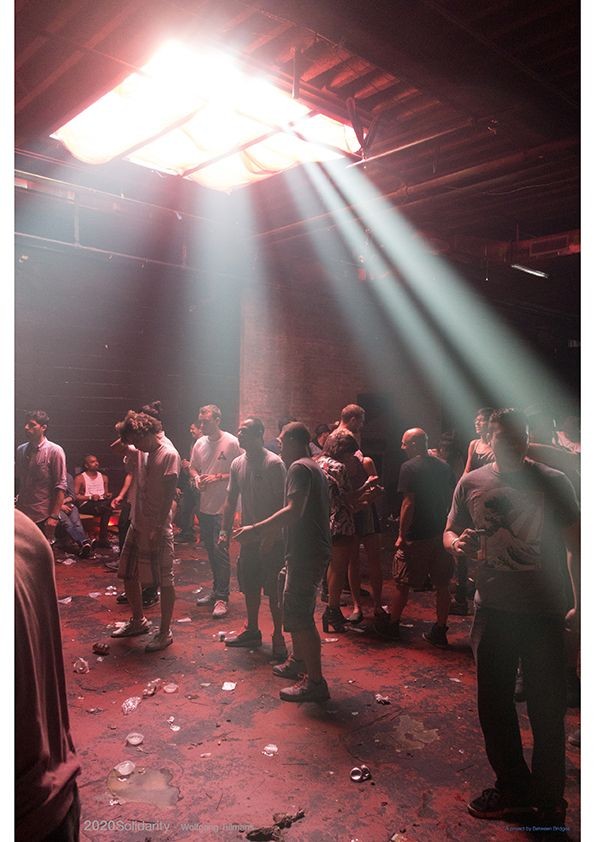

The strongest moments in the exhibition are those that celebrate the experiences of actual people, not bizarre computer-driven smarchitecture. In the section dedicated to the “rural urbanization” of China, a documentary-style video invites us to shadow a couple through their day-to-day life navigating the high-tech and the traditional: rising early in their rebuilt “village” of high-rise towers; out to a sea of automated greenhouses for work, and then back to the city for some calisthenics and socializing with their neighbors at night. In another, we meet refugees who’ve given new life to once-dead towns in Southern Italy and the German Rhineland. In a memorable image, four smiling new arrivals carry a processional statue of Jesus, resuscitating a Catholic tradition the elderly populace of the town were unable to practice in years.

Installation View of Countryside, The Future, February 20–August 14, 2020. Image by Laurian Ghinitoiu. Courtesy of AMO.

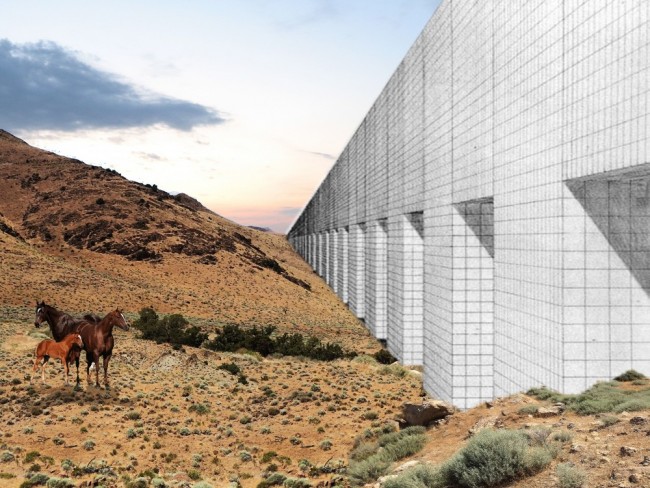

Yet, as the show peters out in the upper rotunda into a trade show of techno-futurist contraptions and enigmatic curatorial pronouncements, we are reminded that Koolhaas himself isn’t all too bothered by the presence of people, or the lack thereof. His current fascination is with the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center (TRIC), a collection of massive white boxes in the Nevada desert housing blockchain servers and Tesla giga-factories. In the exhibition catalog, he calls this “corporate utopia” without planning or people “a brave new architecture born beyond our attention, without any symptoms of humanism.”

The Martian strategy is by definition alien. Visit, learn: this is the future that is waiting for you. But ask: Is TRIC the architecture you want? We may have been ignoring our place in the countryside for a while, but we shouldn’t ignore our place in the future too.

Text by Andrew Pasquier, a New York-based freelance writer, researcher, and global program lead at the Urban Design Forum, a non-profit gathering designers, developers, and civic leaders to debate issues facing the contemporary city.

All mages courtesy AMO/OMA unless otherwise noted.