HOTHOUSES: Architecture And The Onslaught Of Heat Fatigue

Individual window-mounted room air conditioner, such as this one by Frigidaire, are available starting at 200 U.S. dollars.

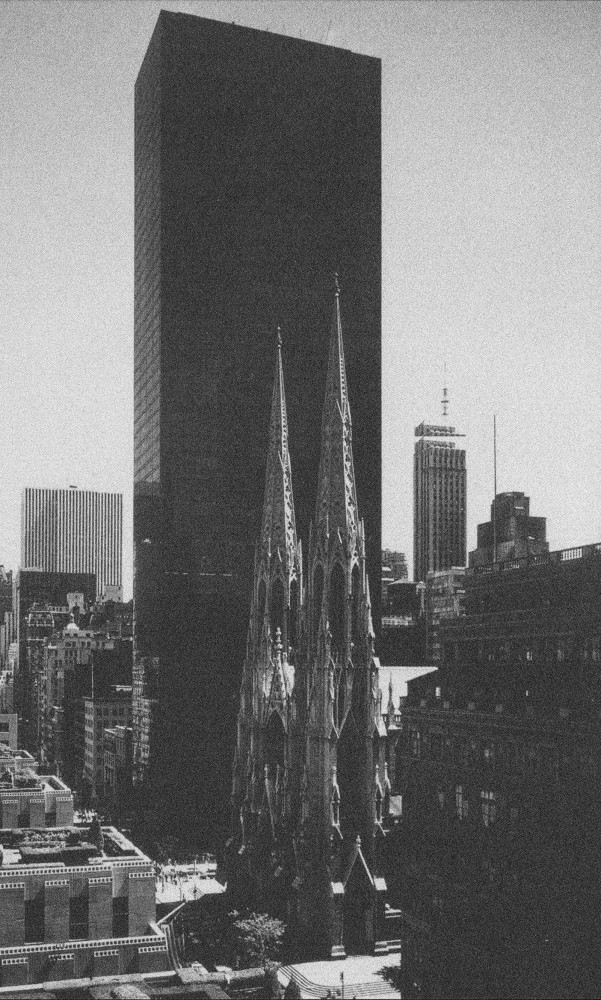

In 2018, in a special report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change described what a temperature increase of 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels might look like: a greater probability of droughts; more of Earth’s landmass affected by flooding and runoff; heavier rainfall from tropical cyclones; an increase in vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue fever. Frozen permafrost soils will thaw, causing irreversible loss of stored carbon. Instabilities in ice sheets could lead to rising sea levels. Entire ecosystems will shift. And wildfires will break out — a lot more of them. There is no single “1.5 degrees Celsius warmer world,” the report cautions. Some parts of the planet have already experienced temperature rises greater than 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. Climate change is what is called a threat multiplier: barring a political revolution overnight, its impacts will be uneven, exacerbating inequality and poverty. Densely built cities are their own kind of multiplier, creating heat islands that boost indoor temperatures, which in turn prompts air-conditioning use. In the most extreme cases, modern buildings not only perpetuate ecological devastation but simulate a hellish future — sometimes absurdly so.

Corner apartment in The Beacon, a 595-unit condominium building in San Francisco whose units suffer from severe overheating.

Residents of The Beacon, a 595-unit condominium in San Francisco, have alleged, in court and on Yelp, that construction and design defects caused such severe overheating that apartments were rendered uninhabitable at times. Like many mid- and high-rise apartment buildings that have sprouted up in American cities this century, The Beacon (architects HKS Inc. and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 2005) makes liberal use of glass. “We had a FULL DAY of sun in our unit anytime it was sunny. There were four windows total that created minimal air circulation (we had to purchase a portable AC unit). I also had to tie sneakers to the windows to prop them open,” writes Karen A. in a 2015 Yelp review of the condo that reads like Jacques Tati’s Playtime for the Anthropocene. “It could have been 65 degrees Fahrenheit out and it was still shorts-and-tank-top weather in our unit. Expect sun-facing units to be at LEAST 10–15 degrees higher and then minus the possibility of airflow. You will be told you can do things to your unit to cool it down. Special UV shades or film on your windows, etc. I can tell you that the tenants/community email each other frequently asking if anyone’s investments into these alternatives have worked.”

The Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, designed 1945–51 by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for Edith Farnsworth.

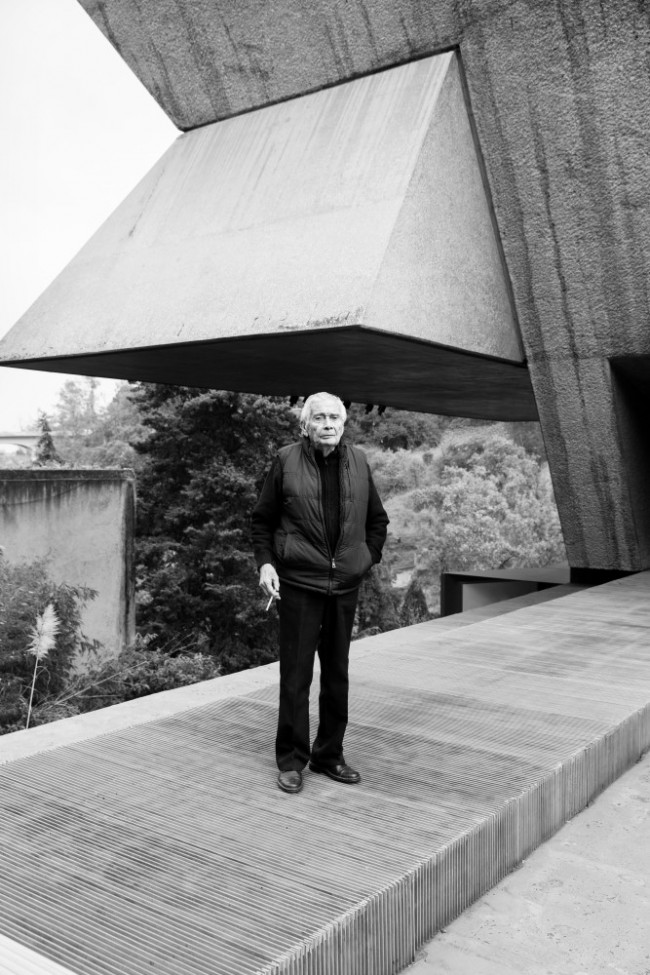

The Beacon’s architects argued that these conditions stemmed from value engineering by the developer, not the design. But, as history shows, a generous budget and even critical recognition is not a guarantee of thermal comfort. When Edith Farnsworth sued her architect, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, for cost overruns on her 1951 namesake house, financial loss wasn’t the only thing she was having to endure. Sun protection consisted of silk curtains and the canopies of surrounding sugar maples, both of which were insufficient for a glass box in a humid Illinois climate. Electric fans installed in the floor augmented natural cross ventilation, assuming the east entry door and west hopper windows were both open, and the wind was blowing in the right direction. In a book on the house, critic and Mies biographer Franz Schulze offered in defense that Midwesterners “were long accustomed to enduring summer heat in their homes.” Besides, he added, air-conditioning was not yet common in domestic settings in the early 50s.

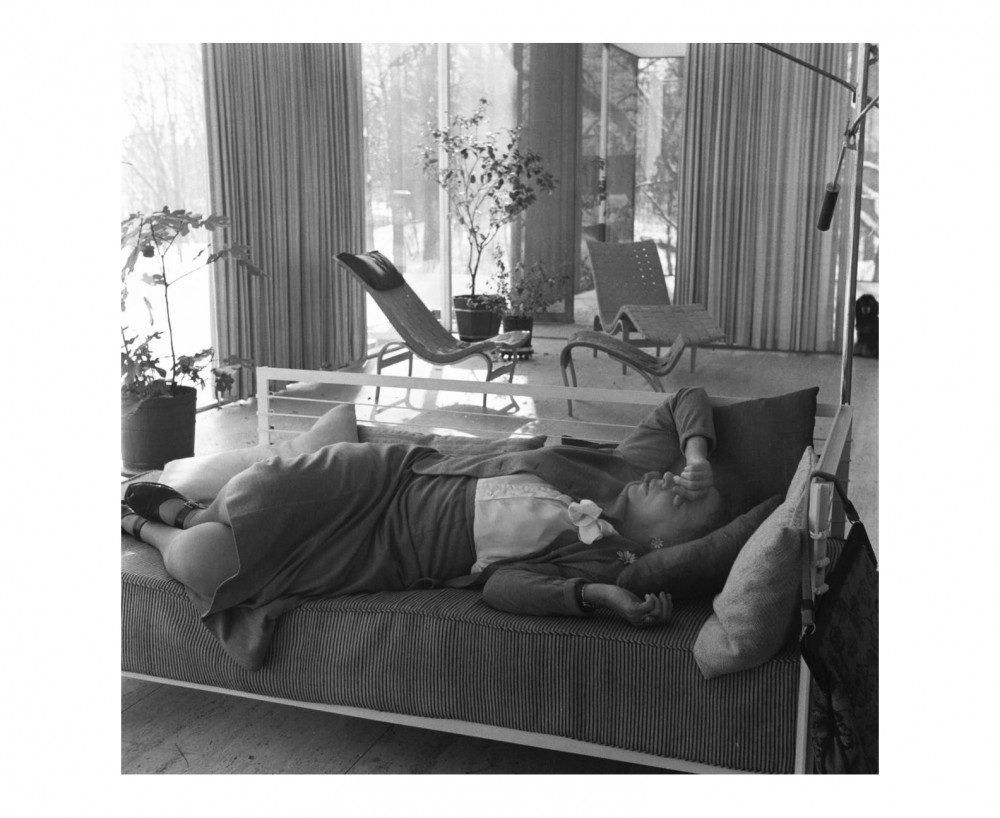

Undated photograph of Edith Farnsworth reclining on a daybed, presumably exhausted from the heat. Courtesy and copyright of Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

AC, or the lack of it, wasn’t always an alibi. In his forthcoming book, Modern Architecture and Climate: Design Before Air Conditioning, Daniel Barber describes the history of attempts to control the way the sun affects buildings by architectural rather than mechanical means. Many architects saw their work as a strategy of climatic adaptability, bringing specific thermal conditions into being through design of the façade (louvers, screens, and other shading devices), the siting and orientation of the building, the volume of enclosed spaces, and other strategies. “Developments of Modernism,” Barber writes, “were a means to induce a way of living (l’esprit nouveau, in Le Corbusier’s phrase) in which the building was the essential medium through which to construct adaptable conditions of comfort according to regional and seasonal vagaries.”

Although Barber concedes that “at many junctures this premise of adaptability was overwhelmed by an insistence on normative conditions, especially in the context of architecture’s relationship to economic development and the global spread of capital,” after the widespread adoption of HVAC in the 1960s, architects generally saw little need to understand the principles of climate-design methods or even analysis. In industrialized economies such as the United States, interiors were increasingly cut off from the environmental conditions that surrounded them. From sealed and conditioned rooms we distanced ourselves, too, from nonmodern — or insufficiently rational or scientific — forms of knowledge. “Cultural engagement with the question of how design mediates social and climatic conditions was largely relegated to a kind of nostalgia for so-called primitive cultures that were seen to live in harmony with their environmental surround.”

A two-dimensional shading diagram by Le Corbusier for an Algiers office project (1938).

Today we can no longer speak with such condescension about the past if we intend to have a future. Dominant models of sustainability, which seek to achieve carbon reduction through technical fixes, have proven insufficient: despite significant innovations in energy efficiency — from better insulation and double glazing to smart thermostats — fossil-fuel consumption has continued to rise globally. We need different ways of living, different rituals and practices, different relationships to the sun. We need different design approaches that go even beyond the structured unsustainability that theorist Tony Fry describes as “defuturing.” Edith Farnsworth, in her brush with high Modernism at the dawn of HVAC, sensed a similar imprudence. “Something should be said and done about such architecture as this,” she told House Beautiful in 1953, “or there will be no future for architecture.” To this we must now add: innumerable forms of life, and even the planet.

David Huber is a critic and the founder of educational media Thinkbelt, for which he produces the podcast Interstitial about space and the consequences of our designs.

Taken from the forthcoming PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.