YUGOTOPIA: The Glory Days of Yugoslav Architecture On Display

“Left out” and “overlooked” are some of the phrases used to describe the work under consideration in Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, a substantial survey at The Museum of Modern Art that aims to augment our dominant accounts of history. To this list should be added “lost,” and not in a metaphorical sense. I’m referring to the modular K67 kiosk, a Yugoslav icon acquired by the museum in 1970, summarily exhibited, then loaned to a university on Long Island and never returned. The designer of the kiosk, the Slovenian architect Saša Mächtig, explained this debacle to me over lunch last summer in Ljubljana, recalling a letter the museum had recently sent him apologizing for the error and pleading for help in finding a replacement. At 77, Mächtig has endured personal and professional misfortunes and lived through the protracted decline and messy disintegration of Yugoslavia, but in this matter, he seemed oddly defeated. The first-generation model MoMA wanted, unlike the more commercially successful second, had a small production run, he explained. He didn’t even know where to start looking.

The Kiosk K67 by industrial designer Sasa Mächtig used as tobacco and newspaper stand somewhere on the coast of Croatia (c. 1980s). Courtesy Museum of Architecture & Design, Ljubljana.

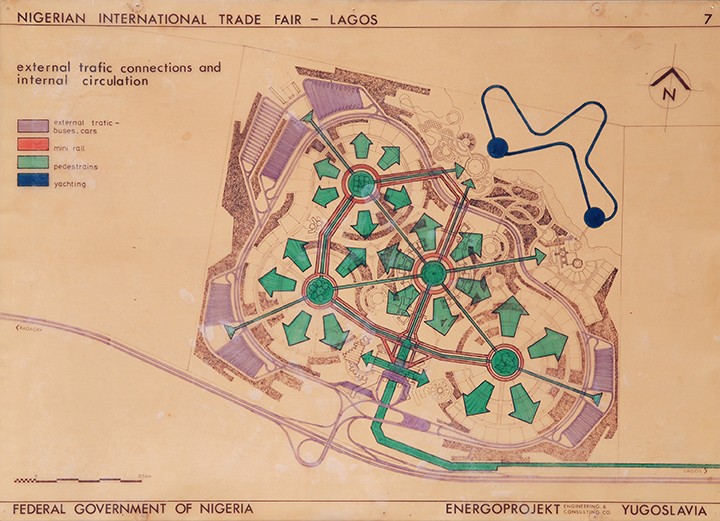

To everyone’s relief, another kiosk was found and beautifully restored. Bright red and lit from inside like a beacon, the fiberglass structure stands proudly near the entrance to the galleries, as if the whole mishap never even happened. MoMA has plenty of reasons to be ashamed, that’s for sure, but guilt is an undercurrent instead of an overarching concept of the exhibition, which was organized by MoMA’s Martino Stierli and architectural historian Vladimir Kulić, with curatorial assistant Anna Kats. The central claim of the survey is that, far from being a cultural backwater or peripheral player, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was, by virtue of its leadership in the Non-Aligned Movement, uniquely positioned to exchange and integrate knowledge and ideas across divides — both sides of the Iron Curtain but also the Middle East and newly independent post-colonial nations in Africa. Put another way, Yugoslavia’s unique position anticipated the current age of globalism, and studying its architecture will tell us more about postwar modernity than the tired old histories do.

Edvard Ravnikar (1907–93); Revolution Square (today Republic Square), Ljubljana, Slovenia (1960–74), Northern view (2016); Digital reproduction, 60 × 75" (152.4 × 190.5 cm). Commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph by Valentin Jeck.

Most museumgoers — who aren’t up on metahistorical debates and probably can’t tell overlooked architecture apart from the canonical — will wonder at some 400 drawings, models, photographs, films, and, occasionally, full-scale objects like the K67, and counter-narrate in their head. “They actually built that? Yugoslavia wasn’t a Communist country?” The first of the show’s four sections, “Modernization,” does much of this contextual groundwork, beginning in 1948, the year Yugoslavia broke with Stalin’s USSR and, under the leadership of the charismatic strongman Josip Broz Tito, pursued a form of socialism based on workers’ self-management. A flurry of building activity swept through a still largely rural society that had only a few years earlier been occupied by Axis powers. Industrialization and urbanization were the twin engines of modernization and essential ingredients for engendering a socialist society governed by the working class. The most ambitious project was the creation of a massive new federal capital on marshland in Belgrade, comparable to Brasília and Chandigarh in both scale and the application of Corbusian planning principles.

Urban Planning Institute of Belgrade, Belgrade Master Plan, Belgrade, Serbia Plan, 1:10000, 1951 (1949–51); Ink and tempera on diazotype, 62 5/8 × 89 3/4 × 1 9/16" (159 × 228 × 4 cm), Frame: 64 9/16 × 52 3/8 × 1 3/4" (164 × 133 × 4.5 cm). Urban Planning Institute of Belgrade.

Though New Belgrade may have been the administrative heart of the new socialist state, in everyday life, as Kulić writes in his catalogue essay, “pan-Yugoslav unity was more effectively performed through the networks of architectural programs distributed across the country.” New schools, libraries, community centers, hospitals, museums, and other public facilities supported a “social standard” of free educational, health-care, and cultural services available to all. Seeing this agenda as exceptional, and so without an easily assignable model, architects were pushed to experiment. Concrete was the material of choice, contributing to wide spans and sculptural form, but the aesthetic of the social standard was in no way as coherent as its ideology.

Milan Mihelič (born 1925); S2 Office Tower, Ljubljana, Slovenia (1972–78), Exterior view (2016); Digital reproduction, 90 × 72" (228.6 × 182.9 cm). Photograph by Valentin Jeck. Commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

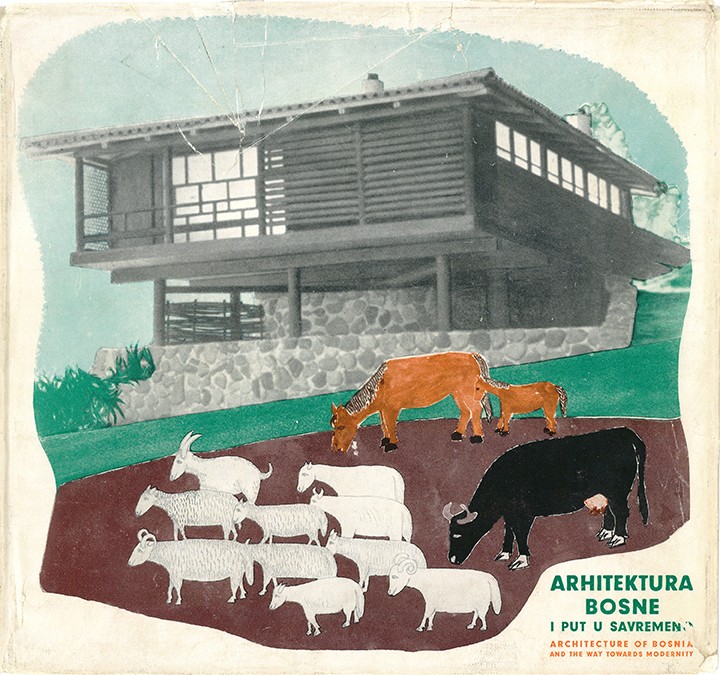

Heterogeneity was a byproduct of a wider governmental policy of decentralization and a reflection of the role of architecture in reconciling diverse ethnic populations spread across six republics and two autonomous provinces. Regional idiosyncrasies were explicitly cultivated by designers. For instance, Juraj Neidhardt advanced a Bosnian Modernism rooted in traditional Ottoman architecture (his ethnographic studies of vernacular culture are a standout in the exhibition, specifically the sketches and photo collage), while Edvard Ravnikar extended the traditions of Central European Modernism through his significant built work in Slovenia and teaching at the University of Ljubljana.

Dinko Kovačić (born 1938); Mihajlo Zorić (born 1939); Building block on Braće Borozan Street, Split 3, Split, Croatia (1970–73), Exterior view, (2016); Digital reproduction, 48 × 60" (121.9 × 152.4 cm). Photograph by Valentin Jeck. Commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Local references did not preclude global influences. Ravnikar’s student Vladimir Braco Mušič, together with Marjan Bežan and Nives Starc, redefined Yugoslav urban planning with Split 3 (1968–c. 1982), an astounding residential neighborhood for 50,000 inhabitants that was inspired by Kevin Lynch, Team 10, and Japanese megastructures, but remained cognizant of the coastal topography and traditional Dalmatian street structure. Another student, Mächtig, fused his teacher’s emphasis on tectonic legibility with an individual interest in British and American consumer culture and Italian industrial design. Tradition did not preclude reinterpretation either, as evidenced by Šerefudin’s White Mosque (1969–79), located in Visoko, near Sarajevo, and designed by Zlatko Ugljen. Making the bare minimum of concessions to Ottoman conventions, its truncated pyramidal space and lime-green tubular ornamentation are like nothing I have ever seen.

Zlatko Ugljen (born 1929); Šerefudin White Mosque, Visoko, Bosnia and Herzegovina (1969–79), Interior view (2016); Digital reproduction, 90 × 72" (228.6 × 182.9 cm). Photograph by Valentin Jeck. Commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The balance between regional diversity and countrywide unity was delicate, although the monuments, or spomenik, featured in the section of the exhibition entitled “Identities” are quite the opposite. Commissioned by Tito to commemorate, among other things, World War II sites, they’re remarkable for their scale, bold abstraction, and visual razzle-dazzle, which has lent them currency on social media and contributed to their dominating recent interest in the architecture of former Yugoslavia. Seen in relation to everything else in the exhibition, from the perspective of our current neoliberal age that is flush with flashy signifiers and short on essential public services, my desire rushes elsewhere. The monuments look unbelievable, sure, but the idea of a well-functioning, even thriving, civic infrastructure as the backbone of a multiethnic socialist experiment blows my mind. Schools! Libraries! Cultural centers! Swimming pools!

Vojin Bakić (sculptor, 1915–92); Berislav Šerbetić (architect, 1935–2017); Zoran Bakić (architect, 1942–92); Monument to the Uprising of the People of Kordun and Banija, Petrova Gora, Croatia (1979–81), Exterior view (2016); Digital reproduction, 60 × 75" (152.4 × 190.5 cm). Photograph by Valentin Jeck. Commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The remarkable thing about Toward a Concrete Utopia is how much it concerns actually realized buildings. People designed them, extracted the materials used to construct them, built them; people lived and learned in them, and in most cases continue to do so today. These buildings are as participatory as anything — certainly more so than the quasi-agitprop that biennials and museums like to think reflects the political vanguard. What the exhibition presents, to put it plainly, is the most concentrated instance of architectural experimentation allied with a progressive political project that we have in recent history. Of course, the flipside of being a companion to a nation-building effort that would stall after Tito’s death in 1980, and eventually terminate in the 90s with violent ethnic conflict, is that the architecture is saddled with the extremities of feeling. And depending on how you feel, “accomplice” might be preferable to “companion.”

Andrija Mutnjaković (born 1929); National and University Library of Kosovo, Pristina, Kosovo (1971–82), Exterior view (2016); Digital reproduction, 72 × 90" (182.9 × 228.6 cm). Photograph by Valentin Jeck. Commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

This emotional tension is perfectly enacted in the first gallery, where a montage of Yugoslav propaganda put together by contemporary Serbian filmmaker Mila Turajlić rapid-fires, across three screens, scenes of smiling faces, enthusiastic comradery, and industrial showmanship (railroads, power plants, etc.). Turajlić’s piece is equal parts ebullient and sinister, a sensation that is hard to shake even as newly commissioned photographs by Valentin Jeck overwhelm the whole exhibition with their melodrama. Gray skies and desaturated color cast a pall over the photographic subject, arresting the potential of these buildings and giving outsize importance to their symbolic dimension, over and above any other aspect. The desire by the historian-curators to avoid blindly championing the exhibition’s subject I recognize, but the photographs feel like an overcorrection, and partially undermine their endeavor. Some kinds of loss can be easily remedied, as the kiosk replacement shows; other kinds, like the loss of hope, less so. Yugoslavia’s aspirations are too relevant, and models of architecture committed to such a strong social project are too scarce, for us to satisfy ourselves with the empty conclusion that this was all simply a failure.

Text by David Huber. Follow him on Twitter here.

Taken from the forthcoming PIN–UP 25, Fall Winter 2018/19.