BONAVENTURE ADVENTURE: A Hotel History of Downtown L.A. through the Eyes of a Mirrored Hotel Complex

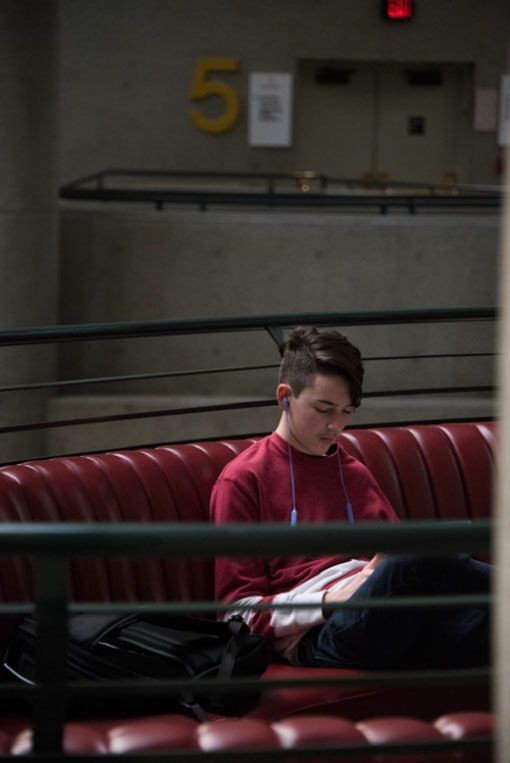

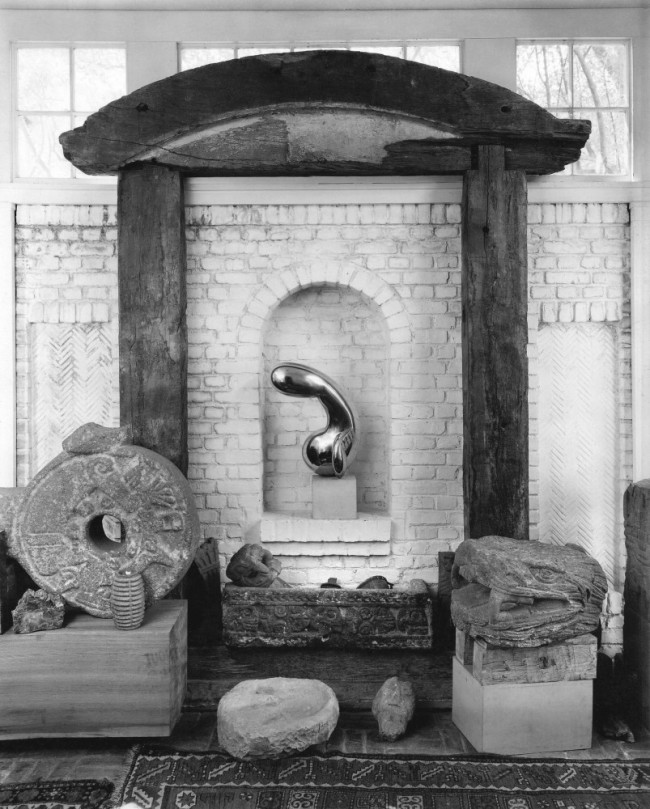

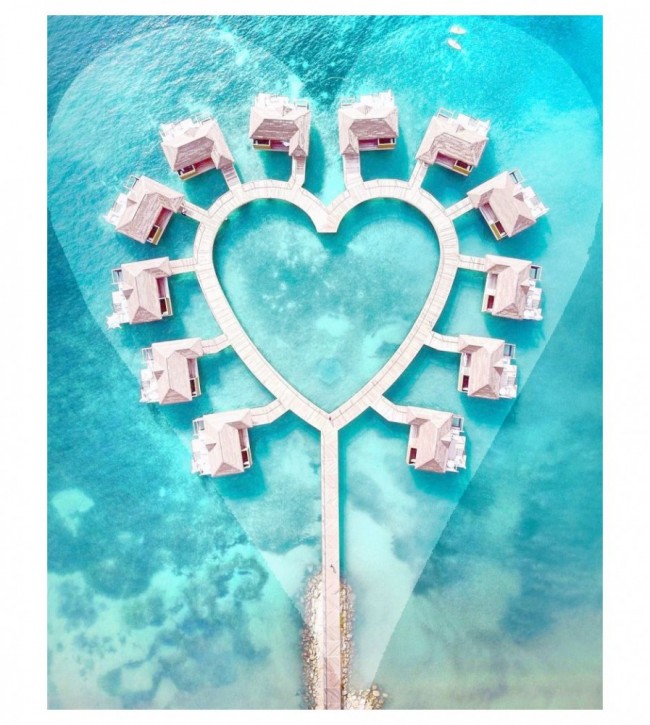

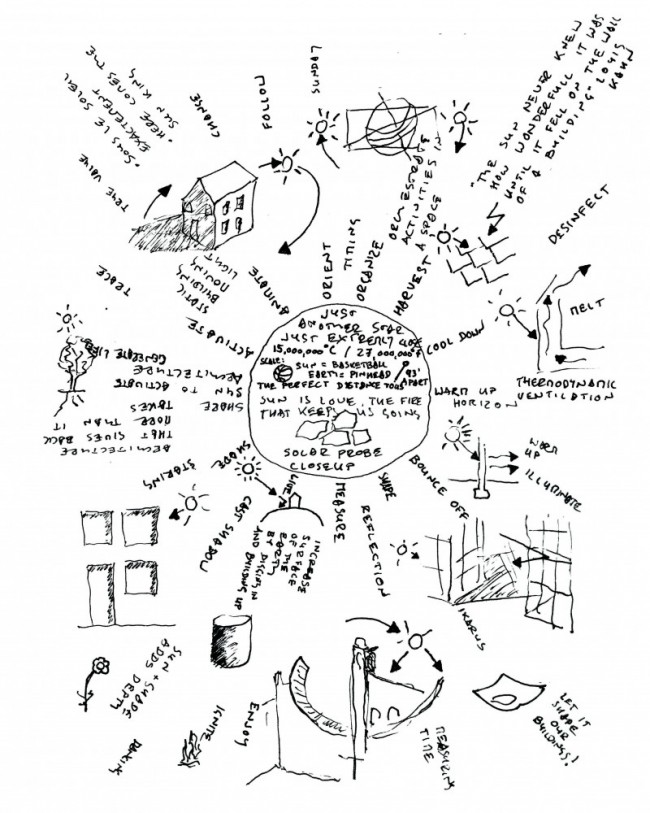

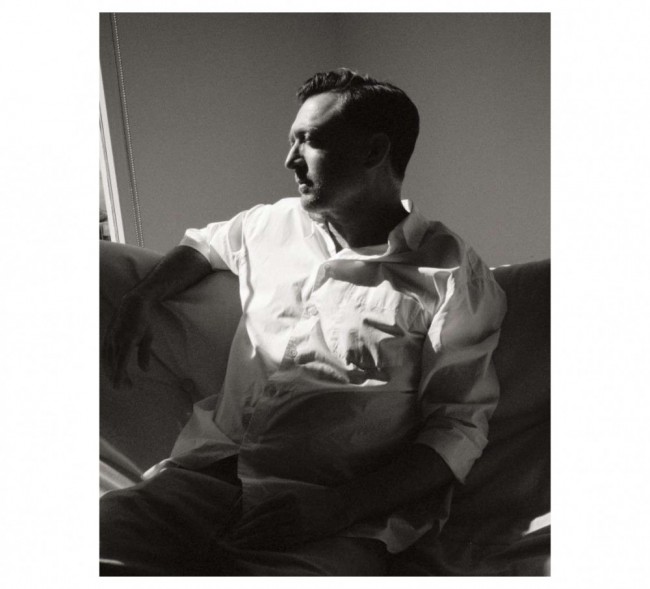

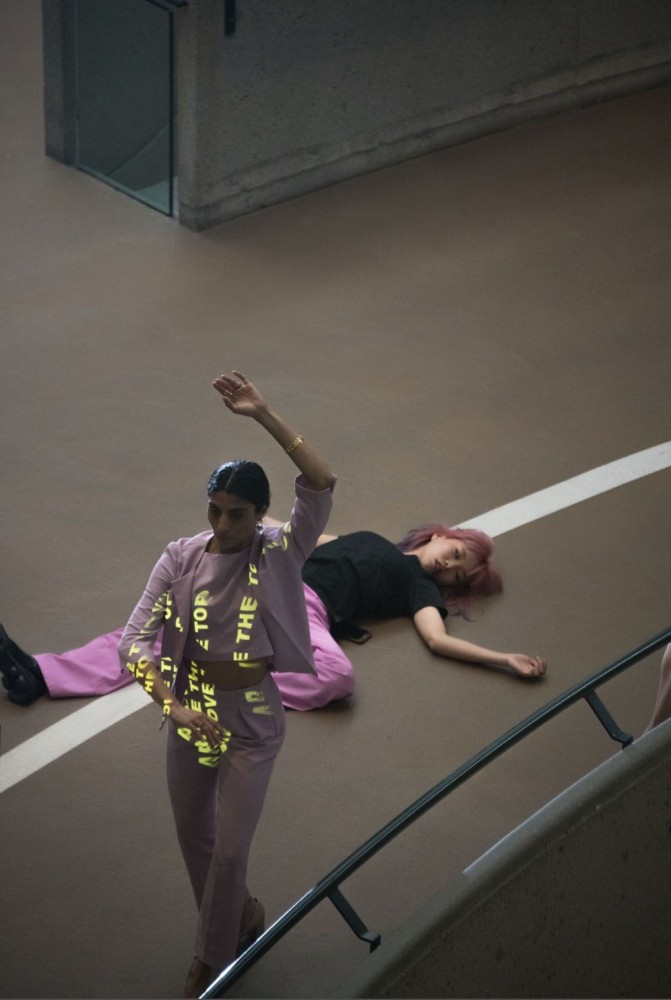

Photography by Torso. Courtesy Atrium. Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

All photography by Torso, in collaboration with Atrium.

Up close, Downtown Los Angeles is a 20th-century movie set meets an Instagram backdrop: vacantly photogenic. Gentrification is on. It’s been tried before, wildness followed. Called by another name: failure. It’s what some people who love L.A. love about L.A.: things bloom readily, vividly here, but like flowers of the Angelonia genus, rarely more than once. (A trick of the light maybe. SoCal’s sun lends a sheen of aliveness, no matter how deadened the roots below.) Now, flimsy condos are flying up. When not investor-empty, these apartments are leased by millennials who like living in a replica of their suburban childhood bedroom with an open-concept kitchen and film-noir view. Meanwhile, civic activists are worried about the local homeless, who live at what’s now an edge, but could be a new center, according to real-estate developers. Amidst all this currency, there is a monument of stability, a building that looks like four AA batteries united around a C and plugged into a terminal of concrete. Hugged by swirls of highway ramps, in the northwest corner of DTLA, it promises to withstand every generation’s apocalypse.

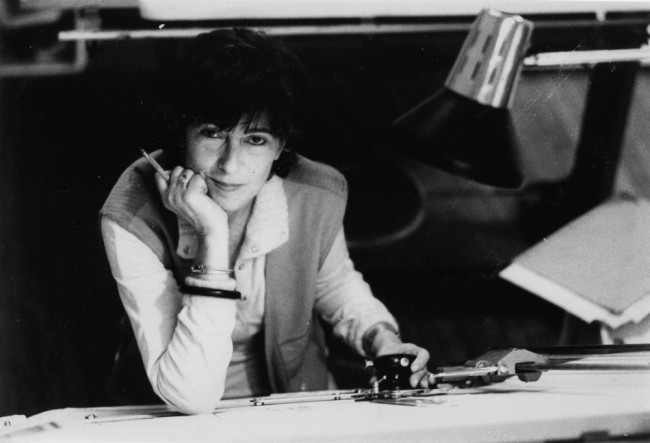

The Westin Bonaventure Hotel was built — Brutalist, futuristic, humane — in 1974–76 by John C. Portman Jr., an architect and real estate developer, whose vertically-integrated business enabled him to erect visions. On the night of Portman’s death, December 29, 2017, I went to the Bonaventure’s top-floor revolving restaurant-bar, as ignorant of his passing as I was of his life. I was there because I was emotional. And there is something secure about the Bonaventure. The building is a theme park: not only does the top floor revolve, there’s a track made for running indoors, and glass elevators that rocket through the roof and up the outside, 33-stories high. I ordered a glass of wine and someone recognized me from Instagram. Also alone, he was there in honor of Portman. I invited him to sit, and he told me all about the man responsible for our setting.

Photography by Torso. Courtesy Atrium. Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

“John C. Portman Jr. got to live an American Dream,” this stranger began... Born in South Carolina on December 4, 1924, on the cusp of the Greatest and Silent Generations (also called, by economists, “the Lucky Few”), Portman didn’t start out with wealth, but made it through market savvy and ingenuity, plus the good fortune of a life that coincided with economic opportunities for educated white men like him. After serving in the navy and studying architecture, he founded a collection of businesses — an architectural and structural-engineering office; a real-estate development firm; property-management companies; and one that bulk purchased his taste in furniture — that together allowed him to construct dozens of iconic buildings across America and Asia. While other would-be starchitects clashed with the business side of their business and vice versa, Portman did it all. “An integrated design-development process,” is how Jonathan Barnett, co-author of The Architect as Developer (1977), described it. Without patronage from a city, king, or dictator, Portman’s ambitious buildings had to succeed in the marketplace, and so they were mostly market places: hotels and malls, convention and trade centers, office buildings, apartment complexes.

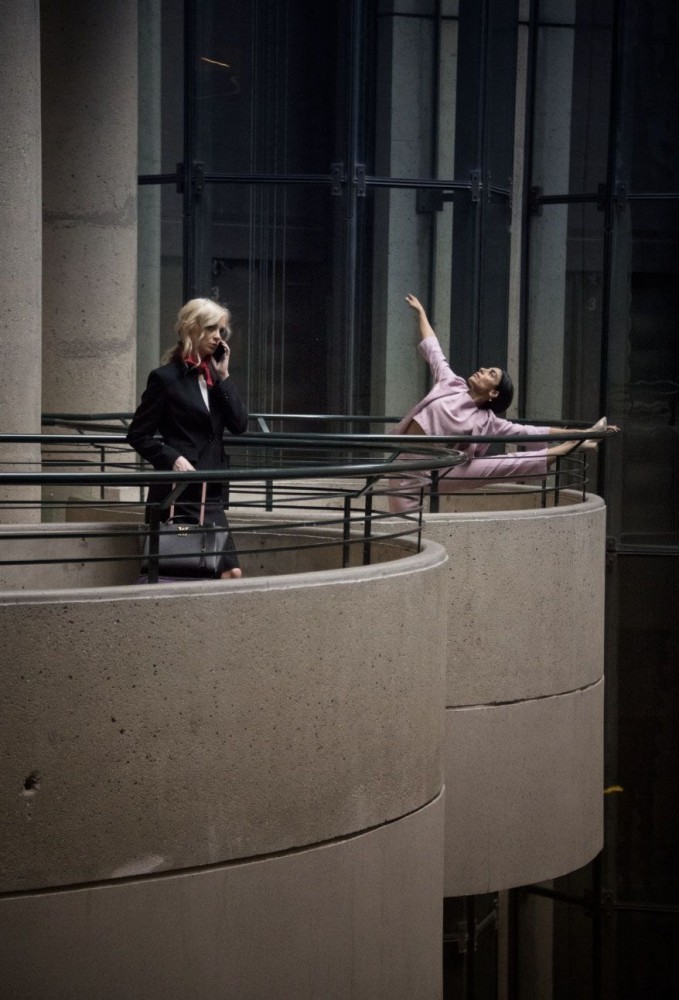

The Bonaventure was built in the first half and at the height of Portman’s career. It features many of his signatures, like a “city within a city” atrium and exposed elevators, all of which he had theories about. “At the cafes in the hotels I have designed,” Portman told Barnett, “there are places where you can watch the movement of the elevator cabs, which become a huge kinetic sculpture… People are fascinated by kinetics.” Portman thought a lot about, “people as creatures of nature,” and how to satisfy our instincts. “I decided that if I learned to weave elements of sensory appeal into the design I would be reaching those innate responses that govern how a human being reacts to the environment.” This meant water and light and plants, places to rest and walk, balconies, open staircases, various vantage points, curvilinear and angular shapes, small and grand scales, all arranged to interact with one another. At the Bonaventure, sunlight refracts through prisms on beveled glass door edges, casting rainbows into the lobby, as it pours down through skylights, reflecting off artificial ponds and through bamboo gardens to create rippling and shafted light patterns on the walls. Sparrows live in the atrium. I hear their chirps every visit.

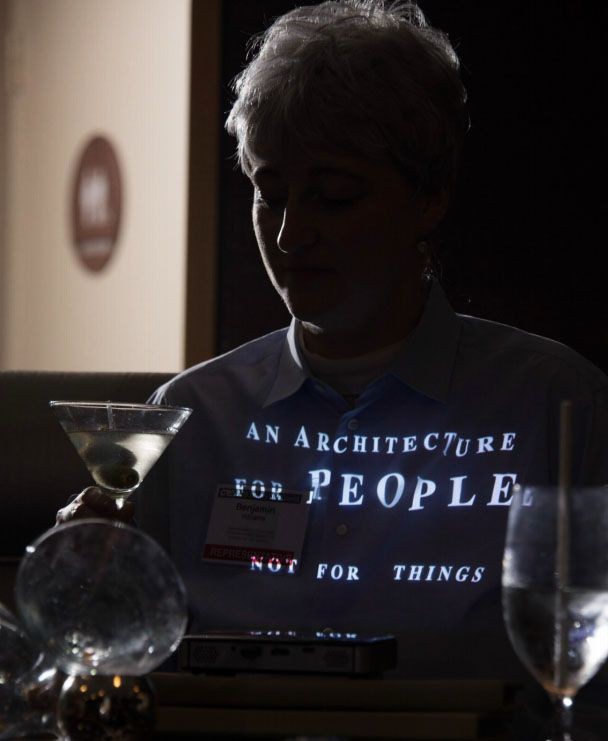

Photography by Torso. Courtesy Atrium. Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

Labyrinthine is a word often used to de-scribe Portman’s structures, especially the Bonaventure. In his 1989 book Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Fredric Jameson famously described the decentering, highly fragmented experience of trying to enter (there is no one central entrance, but many, high and low) and navigate the Bonaventure. The tone of his analysis, and of those who preceded or came after him (Jean Baudrillard in his 1986 book America, Ed Soja on the BBC in 1991, many dudes on blogs), is critical bemusement driven by one-upmanship, as if these men were trying to reassert their dominance after feeling dislocated, small, and bewildered by this building. Baudrillard called it, “nothing but an immense toy,” while for Jameson, this “latest mutation in space,” which he dubbed “Postmodern hyperspace,” had

finally succeeded in transcending the capacities of the individual human body to locate itself, to organize its immediate surroundings perceptually, and cognitively to map its position in a mappable external world. It may now be suggested that this alarming disjunction point between the body and its built environment — which is to the initial bewilderment of the older modernism as the velocities of spacecraft to those of the automobile — can itself stand as the symbol and analogon of that even sharper dilemma which is the inca pacity of our minds, at least at present, to map the great global multinational and decentered communicational network in which we find ourselves caught as individual subjects.

While it’s true it contains shell-like spiraling staircases, rotunda mezzanines, wave-shaped ponds, pod balconies, and other curvy “organic” forms, the Bonaventure is also highly ordered and repetitive in its structure — Albert Speer power-phallic straight in many ways — and so easy to navigate, if you’re paying attention, or accustomed to adapting between more “masculine” and “feminine” modalities (is that the Postmodern condition?). In many ways, the Bonaventure is a microcosm of L.A., with multiple interlocking “neighborhoods” — its four round towers, containing hotel rooms, are flanked by a grid of meeting and ball rooms, and how could I not yet have mentioned that there’s an indoor mall, an outdoor pool, and gardens with skywalks that cross surrounding streets? Like L.A., what the far-flung parts of the Bonaventure share is an atmosphere. Sky god meets earth mother. Discipline meets...

Photography by Torso. Courtesy Atrium. Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

Bewilderment is a state of nature, most acutely felt by those who are excluded — whether by their own soul’s refusal, another’s might, or not knowing the rules — from playing manmade power games. Jameson was irked to be left out. But for poet Fanny Howe, “Bewilderment is an enchantment that follows a complete collapse of reference and reconcilability. It cracks open the dialectic and sees myriads all at once.” Sun, sky, trees, a dentist’s office, the Lakeview Bistro, Starbucks, birds, a travel agency, FedEx, an immigration office, and (the following all unfrequented) a suit shop, spa, bodega, hair salon, and pizza parlor; a piano, “Caution Slippery” signs from leaking ponds, beige carpeting; porn award shows, a Vans conference, tech summits; architecture nerds, JetBlue flight attendants on layover, kids breaking into the pool (it’s easy), teenagers riding the elevators on first dates; memories of all the movies and music videos made here (True Lies, Usher’s “U Don't Have to Call”); and vacancy, a world’s-end-and-we’re-stilldoing-business guilty hush; fate, chance, will to power, and failure. This is what occupies the Bonaventure now. Businessmen, and my freak friends, who, full of ideas, are drawn to empty sites.

-

Photography by Torso. Courtesy Atrium. Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

-

Photography by Torso. Courtesy Atrium. Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

-

Photography by Torso. Courtesy Atrium. Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.

Former Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young called Portman’s buildings “cathedrals to commerce.” The most godly thing about the Bonaventure is its failure to live up to the dreams of its maker. When it first opened, the hotel was lush with flower boxes, hanging vines, high-end brand shops like Céline, and visitors. From 1980–89, a sitcom was set in the revolving restaurant, It’s a Living, also known as Making a Living, which followed a cast of waitresses who dated and fended off their business masc clientele. “What I wanted to do as an architect was to create buildings and environments that really are for people,” Portman once said. “Not a particular class of people but all people.” This democratic ideal, which could be a quote from sweethearts Willi Smith or Keith Haring (the 1980s!), sounds so naïve in a nation with class divides that feel insurmountable. In 2020, the Bonaventure caters almost exclusively to men of Portman’s class. Only corporate accounting could stomach a 60-dollar tab for French fries and a (bad) Cobb salad. But who knows. Labyrinths remind us of life’s unexpected turns and that time brings us back to the same places (buildings, feelings) again and again. The Bonaventure may be due for a fashionable comeback now that Hedi Slimane has dropped the accent from Celine.

Text by Fiona Alison Duncan, a Canadian-American author and organizer. Her first novel Exquisite Mariposa was published in 2019 with Soft Skull Press.

Photography by Torso. .

“Bonaventure Adventure” is presented by Atrium, a site-specific series, curated by Anna Frost with creative direction by Jordan Richman. In collaboration with PIN–UP, Atrium invited writer Fiona Alison Duncan to stay at the hotel and write the text presented alongside the visual portfolio photographed by Torso. Previous Atrium curatorial projects include Nonfood by Sean Raspet and Lucy Chinen, and DIS with Ada O’Higgins and Semiotext(e).

Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.