INTERVIEW: Artist David Hartt Discusses Place, Race, and Black Authorship

This February, the Museum of Modern Art in New York will open Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, the first exhibition at the museum dedicated to the work of African American architects and designers. Curated by Mabel O. Wilson and Sean Anderson, the exhibition presents 10 projects in 10 different cities, designed by ten different architects and designers. It also features a new 15-minute video piece by the Canadian artist David Hartt, whose work uses the built environment as a lens through which to critically capture and analyze cultural, societal, and political phenomena. In conjunction with the exhibition, Hartt collaborated with magazine PIN–UP (in partnership with Thom Browne) on a 16-page special and cover, introducing each of the show’s participants with a short film and portrait, shot via FaceTime on Hartt’s iPhone. Amid the recent controversy surrounding the naming of MoMA’s architecture department, Hartt sat down with Felix Burrichter to discuss his new film, On Exactitude in Science (Watts), and the difficulty of defining Black space.

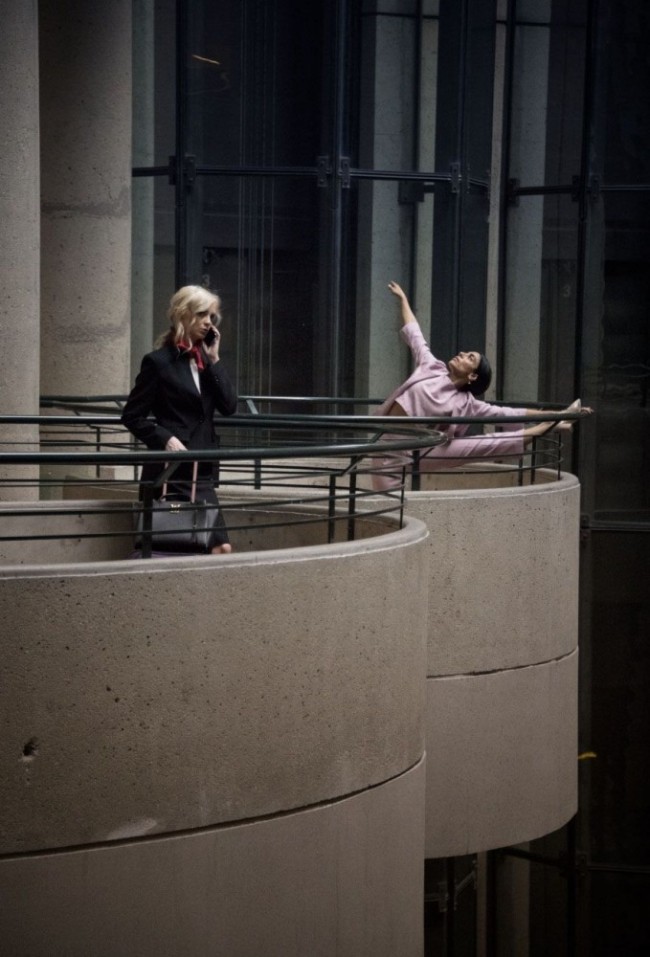

Stills from On Exactitude in Science (Watts), 2021; Single-channel video, 15:47 minutes, (loop); color, sound Monitor 49 1/4 x 86 1/2 x 3 3/4 inches, media player, DAC, cables, custom stand. Commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York for the exhibition Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America.

How did you get involved with the exhibition Reconstructions?

The curators Sean Anderson and Mabel O. Wilson approached me directly. At that point they had already commissioned all the architects and designers in the show. Their work focuses on speculative projects in specific sites in different cities around the U.S., with very specific programs — housing, commercial space, cultural space, etc. that began to address ideas of Black subjectivity, creating space for Black communities. My case is a little different, because I don’t design anything. I like to think that Mabel and Sean asked me because my work uses architecture as a proxy to unpack ideas that surround race, place, economics, and politics. I try to better understand the entanglements that constitute our engagement with the built environment.

What exactly was their commission?

They commissioned a photo essay for the catalog and a film for the exhibition. So those were the only constraints. They also asked me to look thematically at the idea of Black space, which is a very difficult concept to understand. I think that Black space, like any space, is totally contingent on those in it. I think especially today it's become really complicated, because of the way that we choose to live and our influences are so distributed. And there’s the issue of spaces as hybrids. Every space is contaminated with the desires of many different kinds of cultural positions.

And so, to think of a space as insistently Black is already a complicated problem. My immediate thought was: this is going to be hard. I spent a lot of time thinking about how I could characterize a space that addressed the curators’ interests and focus. For me, the best examples were in the form that the commission already took: cinema.

Stills from On Exactitude in Science (Watts), 2021; Single-channel video, 15:47 minutes, (loop); color, sound Monitor 49 1/4 x 86 1/2 x 3 3/4 inches, media player, DAC, cables, custom stand. Commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York for the exhibition Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America.

What kind of cinema were you thinking of?

I almost immediately thought of Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1978) — an important example of a film that captures a concept of Black space. I remember when I first watched the film, at a certain point I gave up on watching it as a kind of linear unfolding of plot, but rather as a series of dramatic vignettes that were unfolding in different kinds of spaces. The film as this connection of all these different environments, whether it’s the kitchen, or the parlor, or the street, or the alley, windows and doors, cracks in the wall, different kinds of permeable apertures that allow for this flow of bodies. There were different scales of domestic spaces from apartment buildings to single family homes. There were also storefronts and the slaughterhouse.

So, you had this complex framework that encompassed all of these different kinds of spatial typologies. And they were all inhabited by Black bodies all doing different things. There were moments of intimacy, of violence, and of play. I proposed that I involve Charles Burnett in the making of my film — because his voice as a historical figure with a unique perspective would be really helpful in terms of how I articulated the space. The curators agreed, and then I contacted Charles; I was really happy that he accepted my invitation. We set up a time to meet the next time I was in L.A. and we had a fantastic conversation about how we might collaborate. My intention was to have him perform an analysis of the spatial typologies that were depicted within Killer of Sheep. But I quickly realized when we actually started doing the interview, that wasn’t his interest. I needed to reassess how I was going to approach it in the moment and be more patient and to listen.

The perspective that he was actually offering was much more anecdotal, about what it meant for him to grow up in Watts and how some of those significant experiences translated into ideas that he might like to film. He would tell me the story about a scene in the film where the main protagonist is negotiating to purchase an engine. What influenced that scene was in fact two or three of his own experiences that he wrote into a singular scene. It was really interesting to hear that non-linear approach to crafting a broader narrative.

Stills from On Exactitude in Science (Watts), 2021; Single-channel video, 15:47 minutes, (loop); color, sound Monitor 49 1/4 x 86 1/2 x 3 3/4 inches, media player, DAC, cables, custom stand. Commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York for the exhibition Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America.

How did you choose the locations for the film?

I did a breakdown of Killer of Sheep into different typological spaces. So really looking at every scene in the film and characterizing it as one kind of space or another: alley or rooftop or apartment complex, factory, shop, living room, porch, etc. Then I looked at Watts and tried to plot out where I might find examples of these kinds of spaces. When I went on a scouting trip to Los Angeles, I introduced myself to a woman who runs Watts Coffee House, Desiree Edwards. Watts Coffee House was both centrally located, but also had played a historical role within the community for many years. It’s in the Mafundi Institute, which was a kind of cultural center that was designed in the late 60s, early 70s. Desiree was instrumental in introducing me to different members of the community.

Watts has a very clear sense of its own history and its own contributions. It takes great pride in terms of the folks who grew up there and how they’ve contributed to culture, sports, and politics, etc. One of the things though, is that like almost any neighborhood in the United States, demographically it’s constantly changing, so fixing the identity of the place’s history in a specific moment is really difficult. Even though it was historically a Black neighborhood, now it’s primarily LatinX communities that live there and you actually see that in the fabric of the neighborhood.

It was important to me to have the work not simply represent the nostalgia of Charles’ recollections, but rather to allow the neighborhood to assert itself as it exists and have the ultimate work be a kind of negotiation between these two states.

Stills from On Exactitude in Science (Watts), 2021; Single-channel video, 15:47 minutes, (loop); color, sound Monitor 49 1/4 x 86 1/2 x 3 3/4 inches, media player, DAC, cables, custom stand. Commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York for the exhibition Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America.

Where does the title for the piece come from: On Exactitude in Science (Watts)?

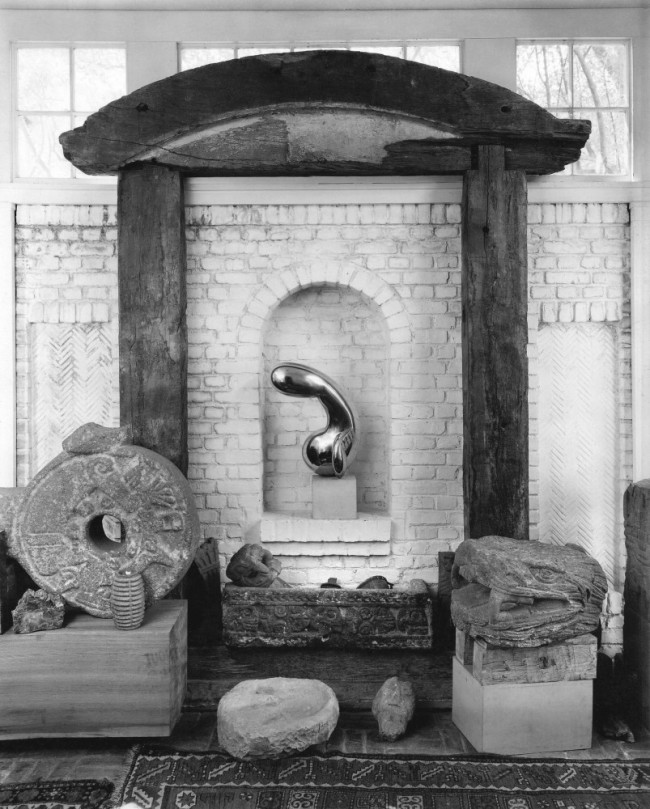

I borrowed the title from a short story by Jorge Luis Borges which is about cartography and the impossibility of representing the totality of space. As I was making my film I realized that it would only be a kind of fragmented representation of the complexity of the neighborhood. In addition to that I also worked with the folks at Actual Objects, Rick Farin, Claire Cochran, and Ainslee Robson. I asked them to develop 3D models of some of the spaces that I was filming. They use this beautiful but rudimentary approach to 3D model making. Instead of using LIDAR, to make 3D models of an existing environment, they used photogrammetry. This involves making thousands of photographs of the site, and then putting them into a program that interprets them as 3D objects. And so even that approach is fragmentary in its nature. And because we rendered them as point clouds they also have a kind of ghost-like quality to them.

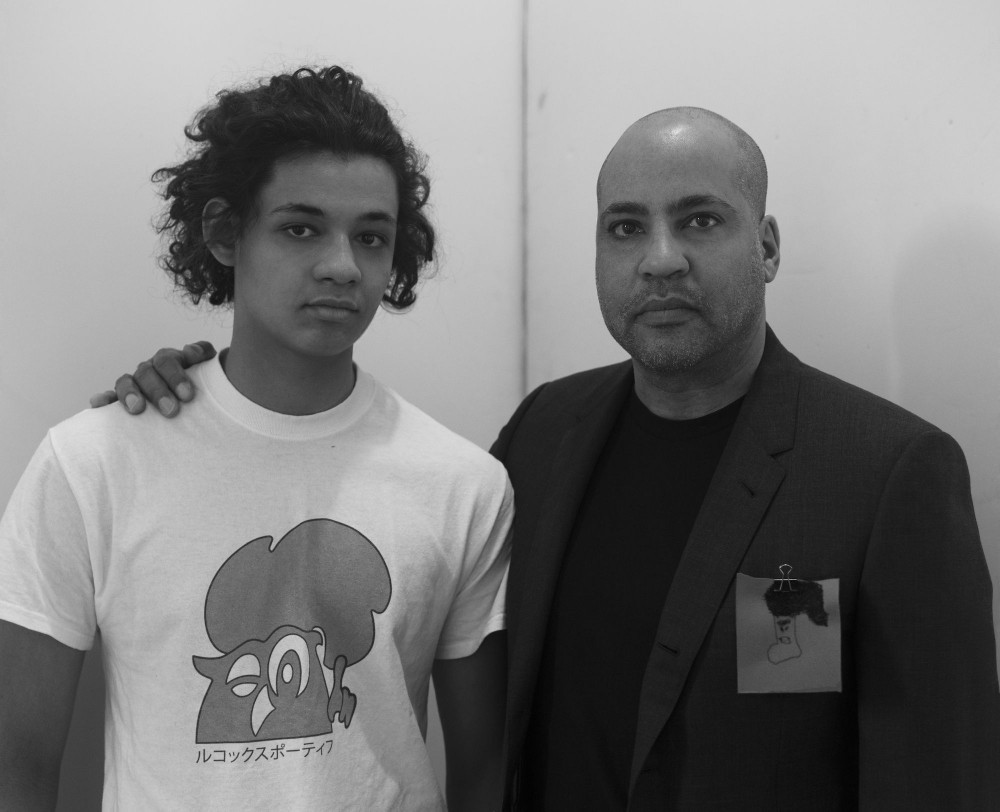

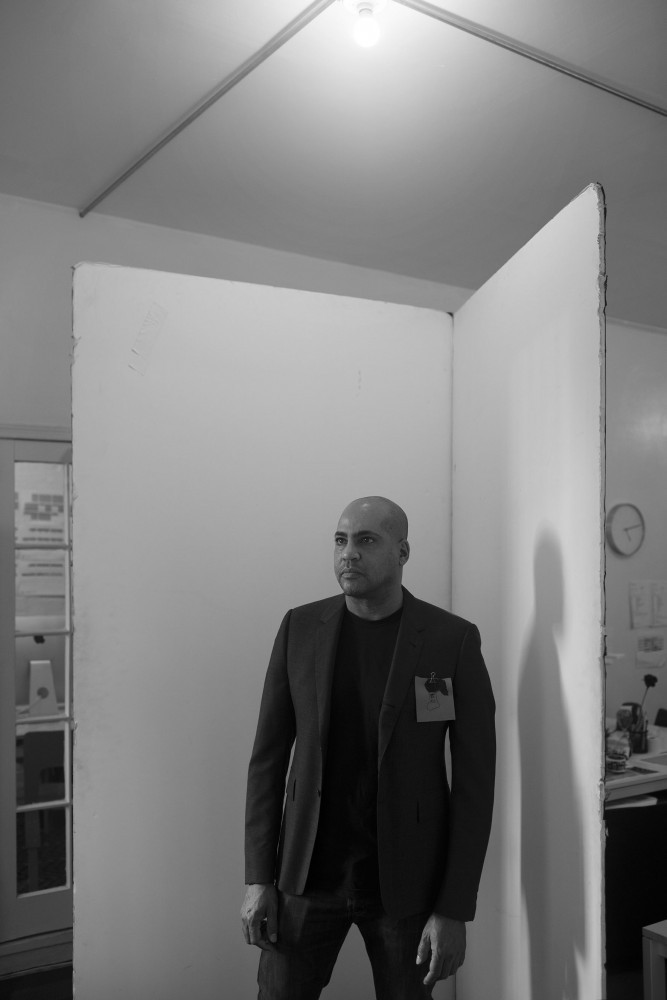

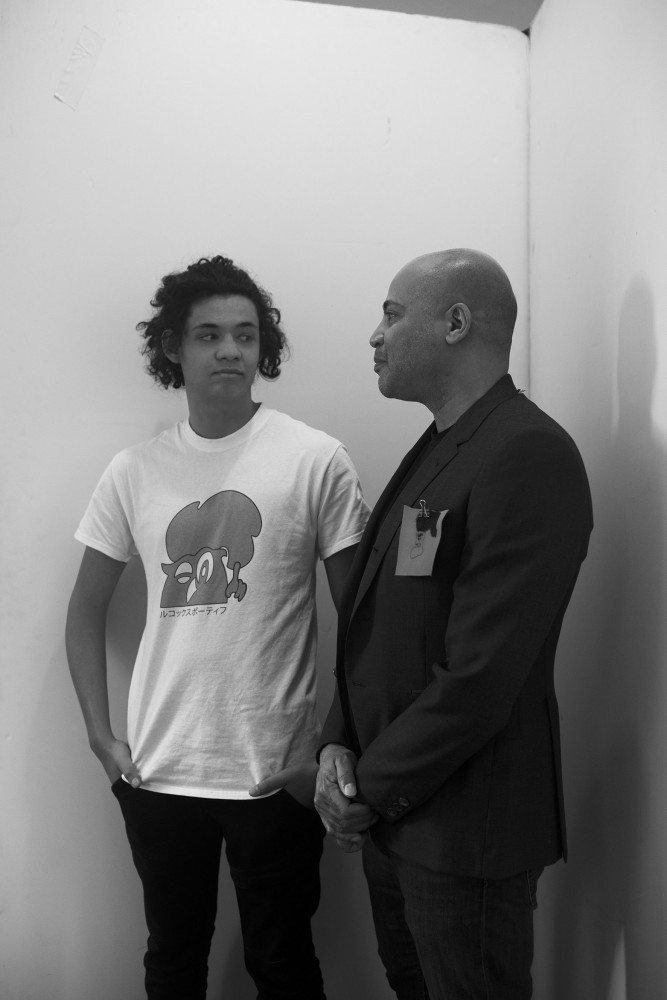

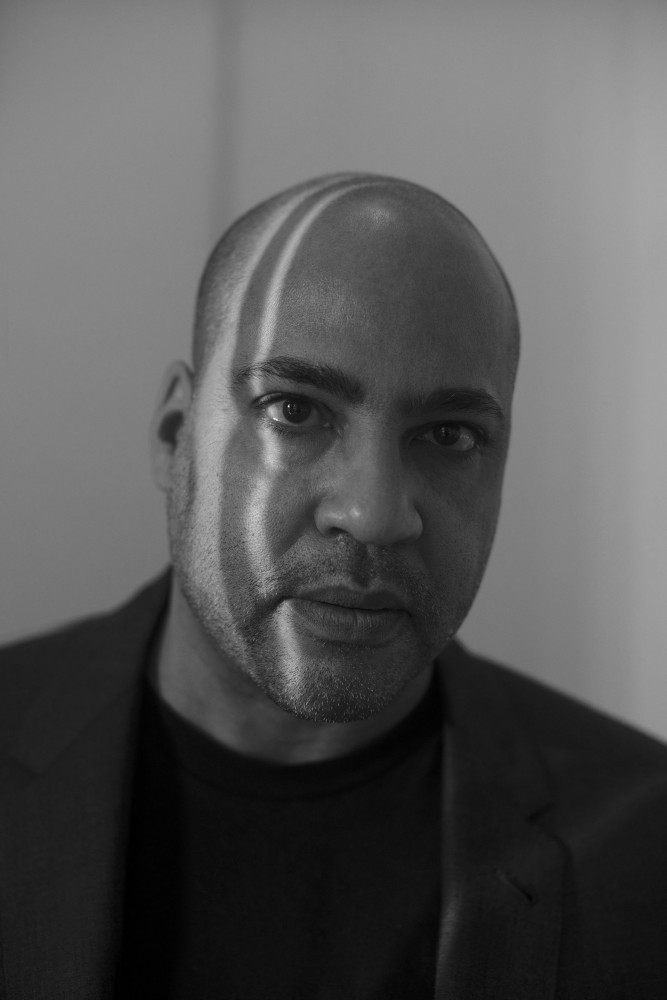

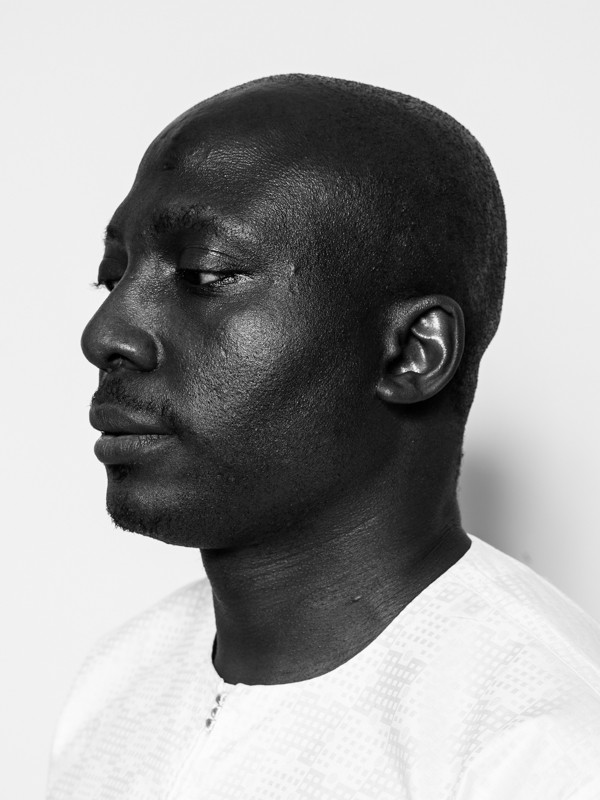

David Hartt photographed by Asger Carlsen for PIN–UP.

You said earlier that spaces carry ideological weight and that you’re interested in the ideologies embedded within spaces. That’s a really interesting question for this exhibition, given that it’s MoMA’s first exhibition in 90 years to even address the work of Black architects and designers.

The fact that MoMA has not significantly addressed the voices of Black architects and designers before is not surprising. But I would have made this piece regardless of whether it was shown at MoMA. It is not the first time that I’ve been thinking about this, about communities, about space, and how we understand those connections between them. If you look at the Beth Shalom project in Philadelphia, it was about being able to use the structure of the building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright to address the history of Jewish and African-American diasporas. Another piece I’m working on right now is for the Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut. The Glass House was built by Philip Johnson, who is protested actively by the Johnson Study Group, led by Mitch McEwen, who’s also in the Reconstructions show. While I appreciate and applaud Mitch’s efforts in terms of trying to address the histories of racism and fascism that are entangled within Philip Johnson’s legacy, that doesn’t prevent me from also thinking about the Glass House as a site that can be productive. I’m not however interested in creating a piece that is about Philip Johnson, just as I wasn’t interested in creating a piece about Frank Lloyd Wright, or about Moshe Safdie. To me they’re all proxies that allow me to discuss the authoritarian aspects of modernism, or issues of colonialism, and so on. The opportunity at MoMA fits within that set of strategies.

In fact, the way the work is sited is very interesting: the seven-foot monitor stands vertically against the huge windows that overlook the courtyard, and more specifically with its back towards all these fantastic buildings on 54th Street. You can even see Johnson’s AT&T building further away, on Madison Avenue. So, all those buildings become the backdrop for On Exactitude in Science (Watts), allowing for a merging of the fabric of the film with the fabric of the city. And that’s part of the assertion of the work: these things are connected, they’re entangled, they’re inseparable. I’m trying to make space for the role of Black authorship and Black creativity within this spectrum of the built environment.

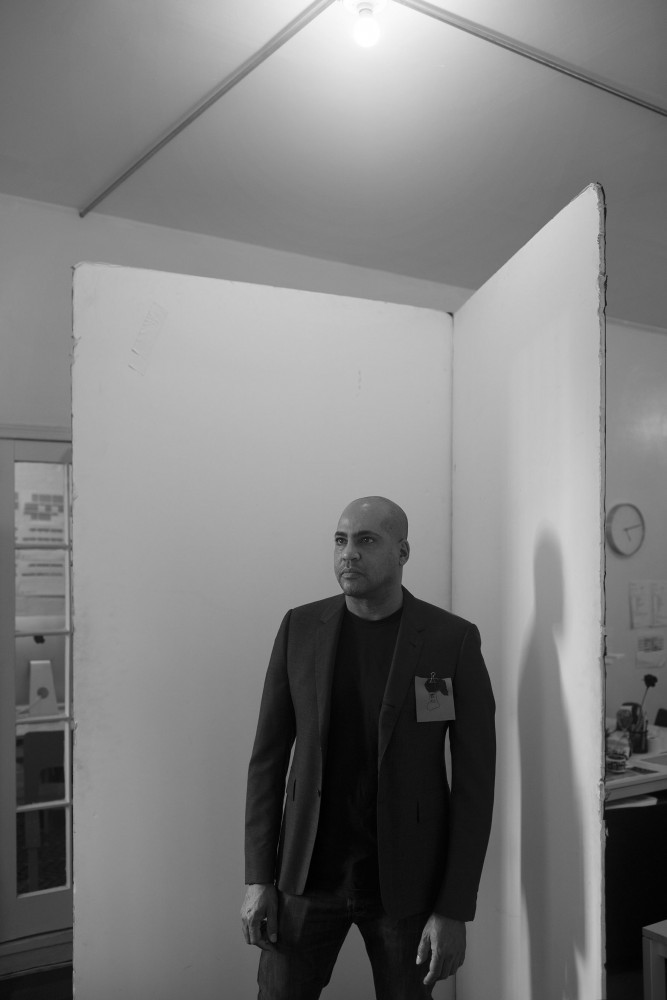

David Hartt with his son Caplan (left), photographed by Asger Carlsen for PIN–UP.

Interview by Felix Burrichter

Portraits by Asger Carlsen for PIN–UP.

Suit by Thom Browne.

This interview is published in collaboration with SSENSE.