HOUSE OF FLUX: David Chipperfield’s New SSENSE Flagship in Montreal

The 19th-century Beaux Arts façade of Montreal's new SSENSE flagship store hides a entirely modern construction by David Chipperfield Architects.

SSENSE is about as with-it as it gets. The Montreal-based online retailer has been a reliable go-to for well-heeled cool-kids in search of fashion’s dernier cri. Founded in 2003, SSENSE has since grown into an arbiter-of-taste with a sizeable global reach, evolving from a digital platform into a formidable (and profitable) brand in its own right with a digital media platform to boot. In light of the company’s online laurels, SSENSE’s recent brick-and-mortar venture might seem somewhat unexpected if not even counterintuitive. However, the new 13,000-square-foot flagship, located in Old Montreal, aspires to be more than just another fancy boutique. Its ambition is to become the logical and physical extension of SSENSE’s digital presence.

The austere functional aesthetic and the content-forward features of SSENSE’s web presence have clearly been carried over into the project’s architectural language. The space is similarly underpinned by a productive interrelation of its form and function, which echoes the irreverently fluid intersections of high and low fashion for which SSENSE is known. Translating the dynamic flux of an online marketplace into a physical space is not without its challenges and the design brief mandated an architectural program fully capable of integrating with SSENSE’s intrinsically cybernetic ethos. The result is a nuanced and iconoclastic speculation on the cultural significance of commercial space in the digital era.

An accessible, flexible, and dynamic program is crucial to the building’s ability to participate in the company’s broader spatial and commercial operations. The viability of this project is therefore fundamentally predicated on its programmatic elasticity, which is encoded into the building’s flexible layout and its unmediated connectivity to SSENSE’s commercial infrastructure. The resulting building is profoundly fit-to-purpose but remains functionally open-ended and reactive to environmental stimuli.

Details from the building's original façade are visible through the windows of the third floor.

SSENSE founder and chief executive Rami Atallah tapped British architect David Chipperfield to revamp a worn-out 19th-century building on St Sulpice Street, facing Montreal’s Notre-Dame Basilica. Most of the existing structure was gutted, but its façade was retained in compliance with the city’s heritage regulations. A concrete slab-and-beam framework was subsequently built around the site’s historical remnants. This domino-like scaffold is essentially a freestanding building tucked behind a grey limestone veneer.

A strict grid is used to dictate the position of almost every detail in the building, from the building’s structural features to its display racks and lighting fixtures.

As he’s previously proven with the design of the Neues Museum (1997–2009) in Berlin, Chipperfield takes a characteristically pragmatic approach to architectural preservation. Instead of conserving the original materials or spatial organization of the 19th-century structure, the building is preserved on a more instrumental level. What is preserved is the architecture’s capacity to participate in social exchange as a functional part of the urban fabric. Working from a clean programmatic slate was clearly important for the architect’s design strategy. Even after its rather unsentimental dismemberment, the existing building’s few surviving vestiges are conspicuously distinguished from the new intervention, keeping them at a polite distance from the new program of the site.

Throughout the building concrete is juxtaposed with the subdued black sheen of the building’s terrazzo floors, echoing Montreal’s ubiquitous concrete architecture.

As a result, the building’s plan is radically functional. It is strictly regimented by a grid, which has been used to dictate the position of almost every detail in the building, from the building’s structural features to its furniture and fixtures. High-tech, multi-functional apertures are located at each of the grid’s nodes, serving as outlets for an innovatively flexible lighting system designed by David Chipperfield Architects in collaboration with Artemide. There are also high-tension steel cables housed inside these outlets, which can be extended from the ceiling to the floor or from wall to wall. These cables are attached to clips that have been cunningly embedded inside the holes of the concrete formwork. The grid is physically manifested in this adaptable web of steel cables, endowing the space with virtually endless possible configurations. It creates a sense of objective order in the space that is still subjectively adaptable. And so in spite of its Miesian rigidity, the grid remains a decidedly supple system of supports for custom-fitted shelves, rails, and display cases.

A skylight generously bathes the seating area in the SSENSE café in daylight. The space is catered by Montreal-based restaurateurs Jason Morris and Kabir Kapoor.

The general detailing of the SSENSE project has the precision and self-effacing, clinical aesthetic of an iPod. The foyer’s weatherproof grating, a necessity during Montreal’s harsh winters, is resourcefully echoed in the tiles of the dropped ceiling behind which the building’s many technical amenities are packed meticulously into this narrow overhead strip. The two lower stories of the building are open-concept spaces that can be used to display merchandise or to host events. The third and fourth floors feature only a handful of spacious fitting rooms, as the boutique exclusively caters to personal shopping. The top floor of the building houses an arty bookstore and upscale café (catered by Montreal-based restaurateurs, Jason Morris and Kabir Kapoor), which have been incorporated as a means of drawing the public into the store. The building is topped with a massive skylight, which sits atop the concrete scaffold like a horizontal curtain wall. Everywhere there is liberal use of concrete, from the structural framework of the building down to its furniture. The coarse texture of the concrete is juxtaposed with the subdued black sheen of its terrazzo floors, both of which chosen to echo Montreal’s ubiquitous concrete architecture, while its grey pigmentation was chosen simply to match the distinctive hue of Old Montreal’s limestone. These material qualities serve as a contextual tether between the building’s aesthetics and its urban environment.

The architecture is machinic, permeated by technologies both visible and invisible. Even shopping is mediated by layers of technical systems. The appointment-based model is a logistical concession that enables any item from SSENSE’s vast repository to be made available in-situ. Once selected from ssense.com, within an hour an order can be delivered from the warehouse to the shop where merchandise is itemized, packaged, and dispensed to a human intermediary via an impressively futuristic vertical lift module, a seemingly mild-mannered machine that is disappointingly tucked away in an employees-only back room. However, there is no lack of visible mechanical and digital technologies in the space and for all its robotic intricacy, the functionality of the building is still totally dependent on SSENSE’s online infrastructure. The building and the website are in fact inextricably co-dependant. This fluid interchange between technology and media is already second nature to SSENSE, so there is no reason why they would expect their flagship to function any differently. The agenda of the space is as much commercial as it is cultural. Under the guidance of Jörg Koch, the creative director of Berlin-based fashion and culture bible 032c, a rolling schedule of diverse events and happenings has been designed to locate fashion alongside art, design, music, food, commerce, and business.

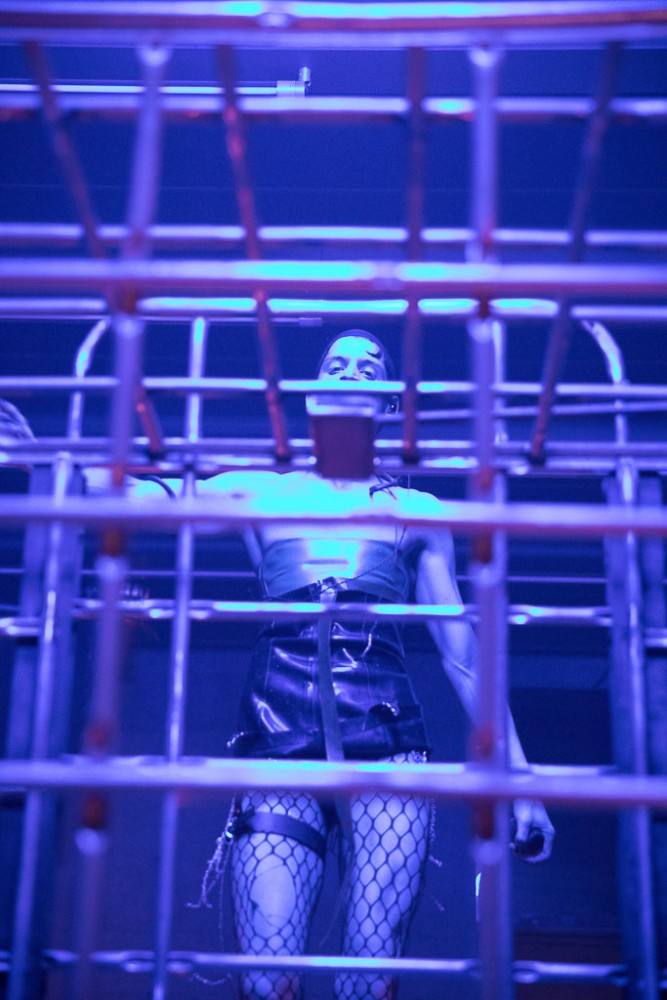

During the grand opening of the new SSENSE Montreal store in April, the musician Arca performed Tormenta, a collaboration with the artist Carlos Saéz.

The first of such events happened during the space’s inauguration in late 2018, during which the gender-bending Venezuelan-born artist and producer Arca delivered an aptly non-conformist performance entitled Tormenta. A film crew tracked the artist as they clambered across a number of installations throughout the building conceived by Arca and Spanish artist Carlos Sáez. Although this initially felt obstructive, it quickly became clear that the camera was an intentional part of the spectacle. Front and backstage were flippantly inverted over the course of a routine peppered by a number of live-streamed diva-worthy costume changes. Arca’s sexualized writhing became increasingly frenetic before the artist was suddenly whisked away into the night on the back of a motorcycle. The following morning, a line of clothing and accessories designed in collaboration between Arca and Prada was revealed, notably featuring headphones in the shape of BDSM headgear for a nonchalant USD 6,450.00 (which even made their way into the New York Post).

With this high-concept performance, turning medium over message and back again, the SSENSE flagship begins to function more like a high-end gallery than a conventional store, asserting that fashion is more than just a commodity, but an essential part of the production and the experience of contemporary culture, with collaborations with Virgil Abloh and Pornhub to boot. This “both-and” quality is not a one-off. Rather, a spirit of multiplicity, of non-dualism, is at the very core of the ethos of the SSENSE. The company describes itself in proudly boundary-blurring terms, as “a retail concept in perceptual beta.” It is an interchangeable left- and right-brain architecture that productively blurs the boundaries of commerce and culture.

One of the spacious fitting rooms, which are part of the SSENSE flagship's services which include tailored fittings and personal shopping experiences.

Guided by Atallah, the company’s leadership is remarkably eloquent and culturally-versed. They are quick to challenge dichotomous thinking and to dispel any inklings of an old-fashioned compulsion to put things into categories. They speak with a vocabulary that has a distinctively post-modern flavor, conjuring Marshall McLuhan but with a defiant avant-gardism more like Pussy Riot, seemingly bursting with unbridled progressivism and techno-futurist enthusiasm. And SSENSE certainly has reason to be optimistic, reaping in a cash flow on the scale of the tech industry while also benefitting from the social capital that is inconceivable to most Silicone Valley technocrats.

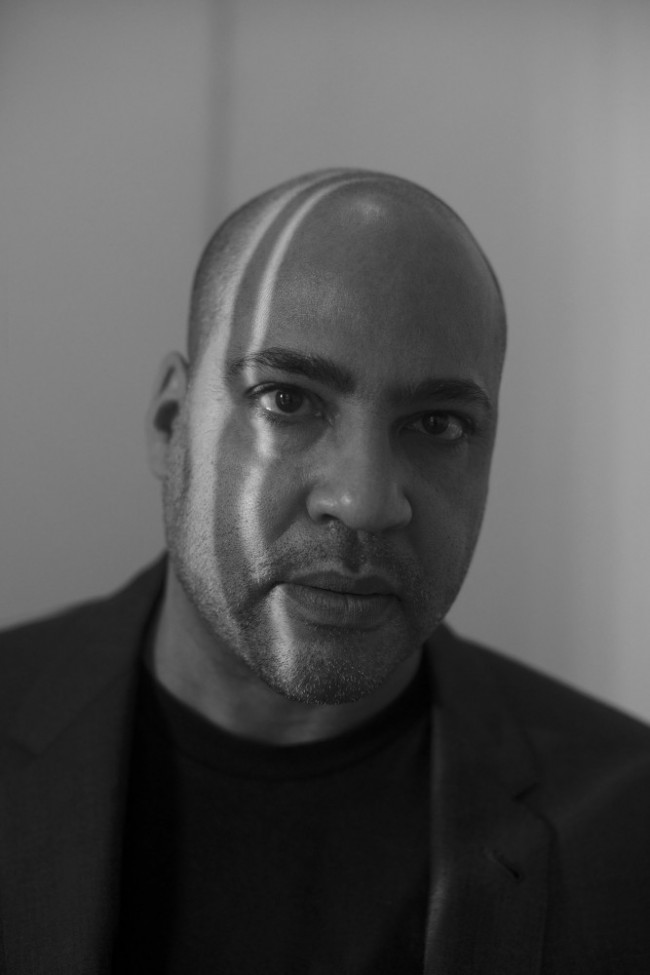

Portrait of SSENSE Founder and chief executive Rami Atallah.

But their success may have also blinded them from some of the glaring realities of luxury retail. They repeatedly assert that blurring the divisions of public and private space is socially enriching, essentially proclaiming retail to be the basis of a sort of contemporary res publica. But this is only really applicable to a very small percentage of society with the purchasing power to unlock the invisible gates of the luxury market. Of course, SSENSE never claimed to have a humanitarian mission, but they would be wise to remember that they are not a universally accessible cultural space either.

But for the audience that has the means to access it, SSENSE has nevertheless been successful in formulating an interdisciplinary commercial program that collides a number of different cultural, economic, and material forces together. Their new flagship is intended as a sort of conduit for a variety of overlapping infrastructures. The company operates out of its headquarters in Montreal’s garment district, where the labor of digitizing SSENSE’s wares takes place. The company’s physical stock is held in a vast warehouse near Montreal’s airport, where it can be imported and exported with relative facility. The new flagship space in the center of Old Montreal is the final piece of this spatial puzzle. Together, they produce a multiplicity between the inner city, junkspace, and the cloud, resulting in a surprisingly robust spatial interdependency. All of these spaces are essential in their own way to the functioning of the company, and each of them has a different land-use value according to their respective function. The store’s commercial operations are transparently tied to the global commercial-economic complex, entwining its flow of physical goods to its more abstract exchanges of capital. This unequivocal incorporation of SSENSE’s material and immaterial structures into the space, perhaps the first of its kind, thus powerfully manifests the distinctly contemporary functional values of its architecture.

Text by Daniel Simon Ayat.

All images courtesy SSENSE.