RECONSTRUCTIONS PORTRAIT: Emanuel Admassu on the global African diasporic

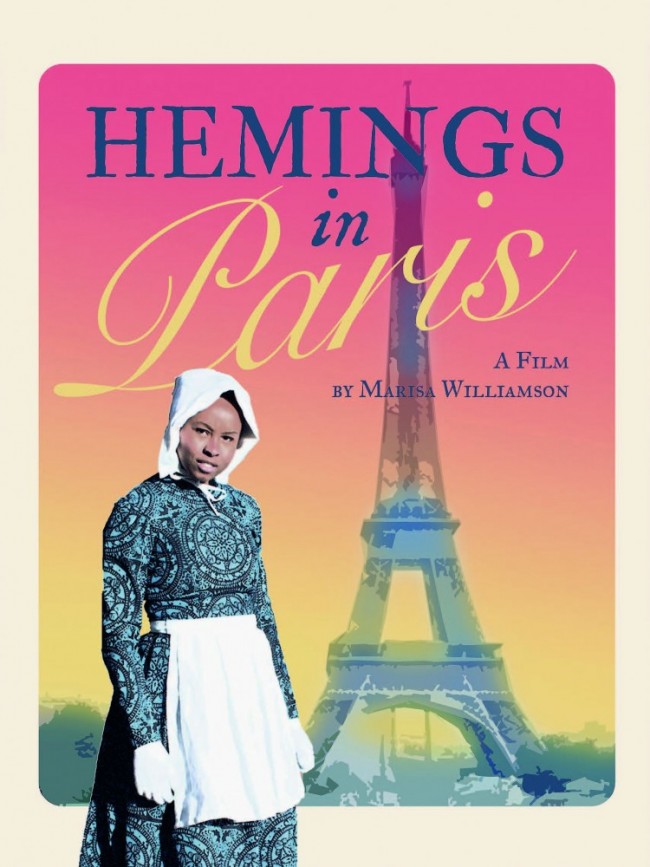

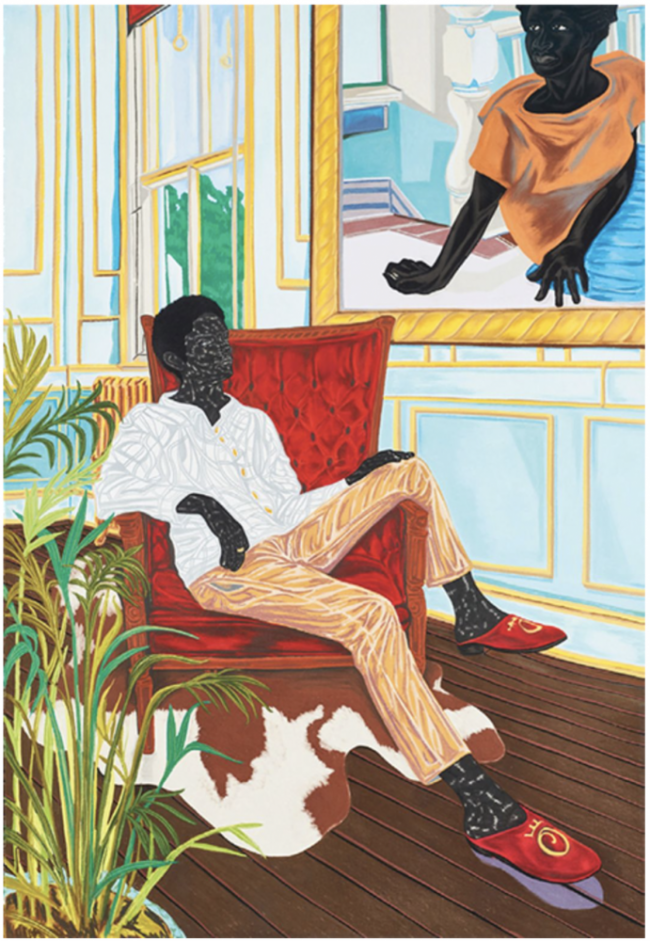

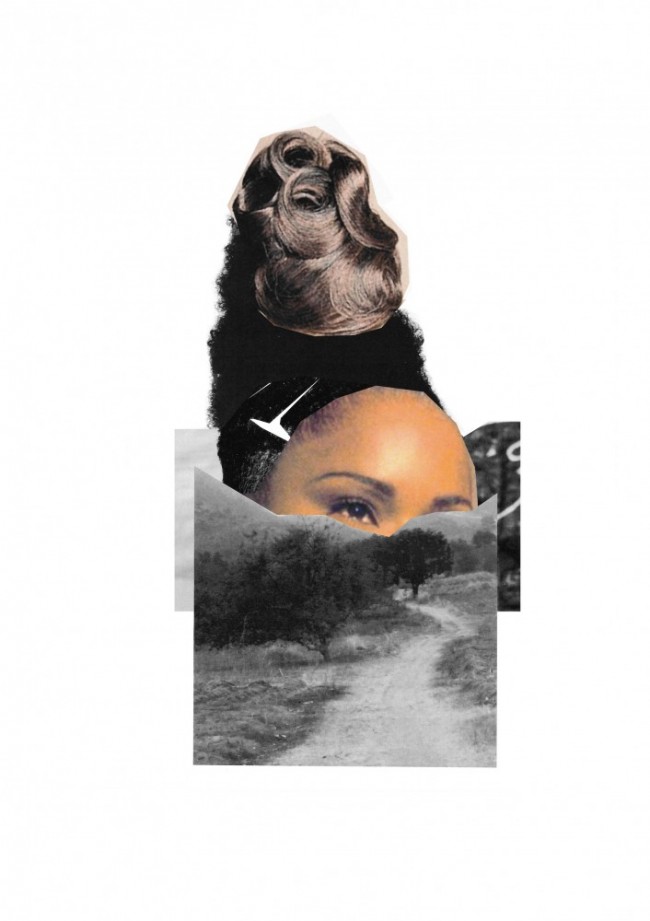

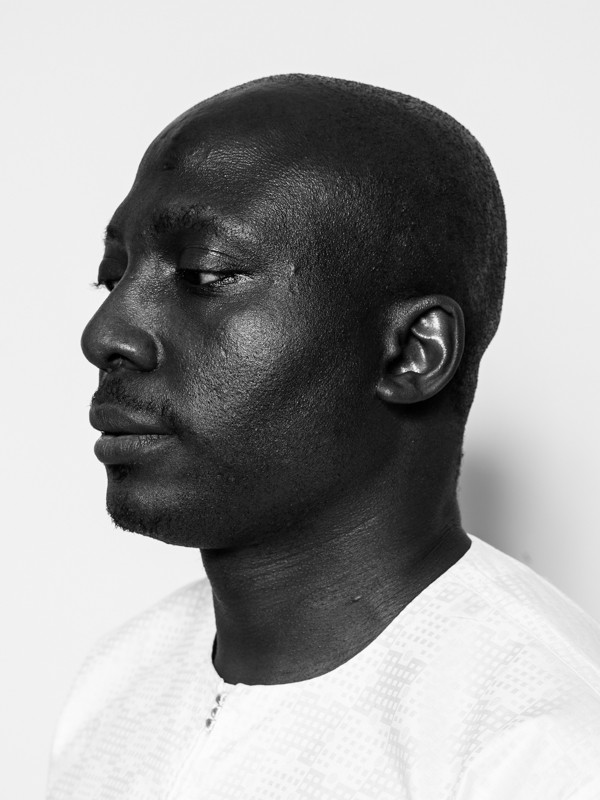

𝘖𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘔𝘶𝘴𝘦𝘶𝘮 𝘰𝘧 𝘔𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘯 𝘈𝘳𝘵, 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵 𝘋𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘥 𝘏𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘰 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘸’𝘴 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘳𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘪𝘦𝘸𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘵 (𝘴𝘦𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘰𝘸). 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗’𝘴 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘚𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘈 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘩𝘪𝘱 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘮 𝘉𝘳𝘰𝘸𝘯𝘦.

Architect Emanuel Admassu is a founding partner with Jen Wood of the practice AD—WO, which works between Melbourne, Australia and Addis Abba, Ethiopia from a base in Providence, Rhode Island. Thinking through global African diasporic conditions, Admassu’s research-driven practice blurs boundaries between art and architecture while proposing new ways of living informed by the specificities of local sociopolitical contexts. He is a co-founder of the Black Reconstruction Collective.

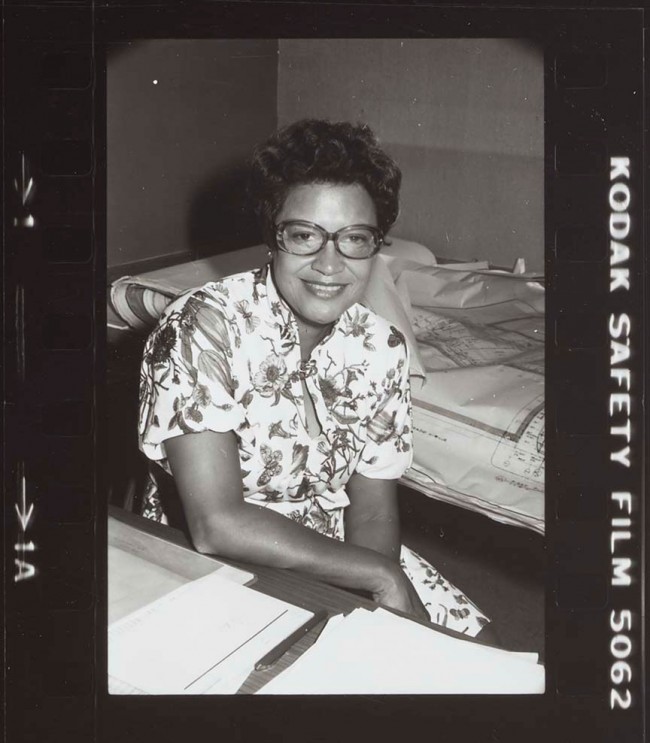

Emanuel Admassu photographed by David Hartt for PIN–UP.

What led you to architecture?

I knew from a very young age that I wanted to be an architect. I grew up in Addis Ababa, a city that has experienced radical transformations over the past 30 years. My father was an electronics technician, so I grew up surrounded by electronics that he was fixing. It was fascinating to witness his ability to get lost in the work. He was an extremely disciplined man who would spend days operating on a single device. My mother, on the other hand, has a great aesthetic sensibility. Once a year she would make us take all the furniture out and reorganize everything. Sometimes the living room furniture would end up in the dining room, artworks would be repositioned, etc. So I grew up in a house where rooms were always being reconfigured and electronics were being disassembled. That might have something to do with it. I’m also the youngest of three children and my siblings are much older. They both moved to the U.S. when I was six or seven years old, so I spent a lot of time alone, drawing — mostly drawing potential houses for different relatives and family members.

How has your practice evolved?

My practice, AD—WO, is a partnership with Jen Wood who is from Melbourne, Australia. We met at Columbia GSAPP. Like most young practices, we started with small competitions we were doing outside of our day jobs. Eventually we moved from Brooklyn to Providence, Rhode Island, and started doing a lot more research and design projects in East Africa — mostly focusing on Addis Ababa and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Over the past few years we have been working on single-family and multi-family residential projects in Addis Ababa in collaboration with local architects. Hopefully one of those will start construction this year. Our primary research project has been the examination of urban marketplaces in Ethiopia and Tanzania. This research produced a lot of knowledge that we couldn’t translate into buildings, leading to a more direct engagement with the art world: creating tapestries, stop-motion animations, drawings, and installations for exhibitions. We have accepted the fact that our practice is positioned between art and architecture.

What does “reconstructions” mean to you? Both as the title of the show and as a historical or contemporary reference?

I believe Reconstructions requires two simultaneous practices: aggressive reinterpretations of history and radical imaginations of the future. The first is based on the need to establish a new value system because the dominant structures and systems for seeing and measuring are based on a settler-colonial logic that was invented to devalue Black life and Black spaces. This is why we need new ways of conceptualizing cities, archives, and disciplines associated with the built environment. For example, what is fascinating about W.E.B. Du Bois’s book Black Reconstruction is the fact that it is a radical re-narrativization of the documents he was able to access — a response to his lack of access as a Black man to traditional archives. This tradition continues with contemporary Black intellectuals who are in some ways redefining or expanding the archive by engaging with an expansive array of images and documents. It is also a rejection of the arguments, meanings, and myths of exceptionalism that were attached to objects in the archive. We need to develop new ways to model and draw undervalued spatial practices by Black folks in the city. In other words, we need to invent ways of seeing ourselves and our spaces differently from the way we have been trained to do so. Because, without establishing that, it would be impossible to have a vision of Black futurity that is genuinely dedicated to freedom and liberation. The second is the practice of imagining a different world. I would say this is an abolitionist practice, following the Black radical tradition, that involves dismantling the systems that continue to destroy our lives and make the planet uninhabitable. This requires an unapologetic vision of a future that is not built on Black social death, a future that is not built on recursive dispossession. It requires instead a future that starts with reparations, then continues to build Black neighborhoods and communities that have been systematically devastated by state-sanctioned violence enacted through policing, banking, urban-planning practices, and the prison-industrial complex. This work has to be done simultaneously with sustained and honest accountings of the history of colonialism, racial slavery, and imperialism that have shaped our contemporary enclosure of racial capitalism.

Can you describe the project you are creating in response to the MoMA Reconstructions brief? Where is it and why did you choose that location?

Our piece for Reconstructions aspires to be in the first category I described above. It attempts a radical rereading of everyday practices, following recent scholarship by Saidiya Hartman, Tina Campt, Christina Sharpe, Mabel O. Wilson, and others. It explores the myriad ways in which Black people have been imagining liberation within spaces of containment. We are examining Atlanta, Georgia, the city I moved to from Addis Ababa as a teenager. It was also the epicenter of the civil rights movement and it continues to be a major hub for Black cultural production in music, television, and film. We’re asking how we can invent ways to represent these everyday practices by people who are living in Atlanta, who are finding ways to occupy the highways, the streets, the parking lots, strip malls, and so on. We are interested in relatively banal and mundane activities that are required to survive as a Black person in this country. It is also an investigation of the danger that lurks behind these seemingly ordinary spaces in the city. The piece is called Immeasurability. Therefore, it is also grappling with this legacy of architecture as a discipline that makes the world measurable, transforming land and people into property. It is a meditation on multiple scales of immeasurability that are practiced by Black people in Atlanta, and how these sensibilities are tied to the movement of Black people across the Atlantic. There are two main pieces in our installation: a horizontal disc operating at the scale of the city and a vertical disc operating at the scale of the planet. The horizontal disc grapples with issues of displacement and dispossession while the vertical disc is trying to understand how a massive planetary scar — the Mid-Atlantic Ridge — functions as a metaphor for the extractive relationships between Africa and the Americas, linking the Door of No Return to the port of Savannah, Georgia, where Eli Whitney patented the cotton gin.

Interview by Drew Zeiba

Video portrait by David Hartt

Editing by Jessica Lin

Music by King Britt presents Moksha Black

A PIN–UP production in partnership with Thom Browne

This video is part of a series of ten portraits David Hartt created for PIN–UP on the occasion of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America at the Museum of Art (Feb 20–May 31, 2021), curated by Mabel O. Wilson and Sean Anderson. The portraits were also published in the print edition of PIN–UP 29.