RECONSTRUCTIONS PORTRAIT: Amanda Williams on the Possibility of Free Space

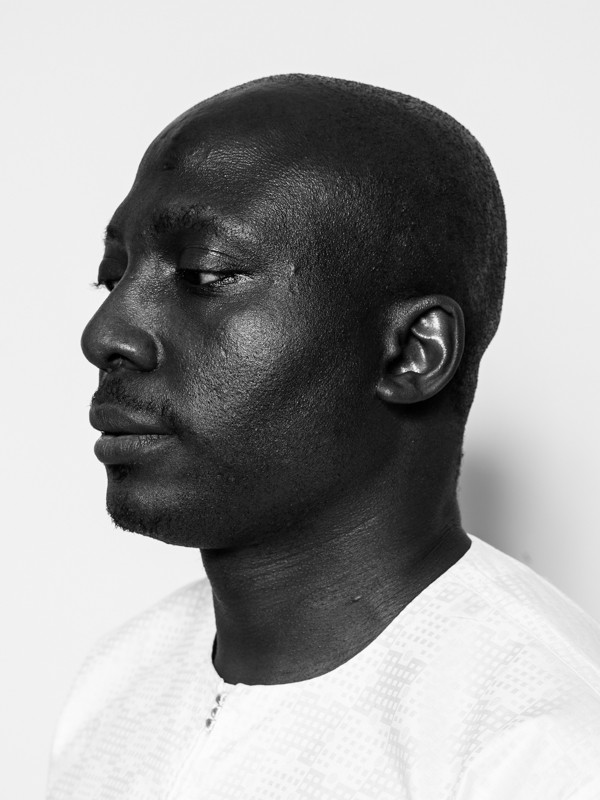

𝘖𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘔𝘶𝘴𝘦𝘶𝘮 𝘰𝘧 𝘔𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘯 𝘈𝘳𝘵, 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵 𝘋𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘥 𝘏𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘰 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘸’𝘴 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘳𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘪𝘦𝘸𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘵 (𝘴𝘦𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘰𝘸). 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗’𝘴 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘚𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘈 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘩𝘪𝘱 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘮 𝘉𝘳𝘰𝘸𝘯𝘦.

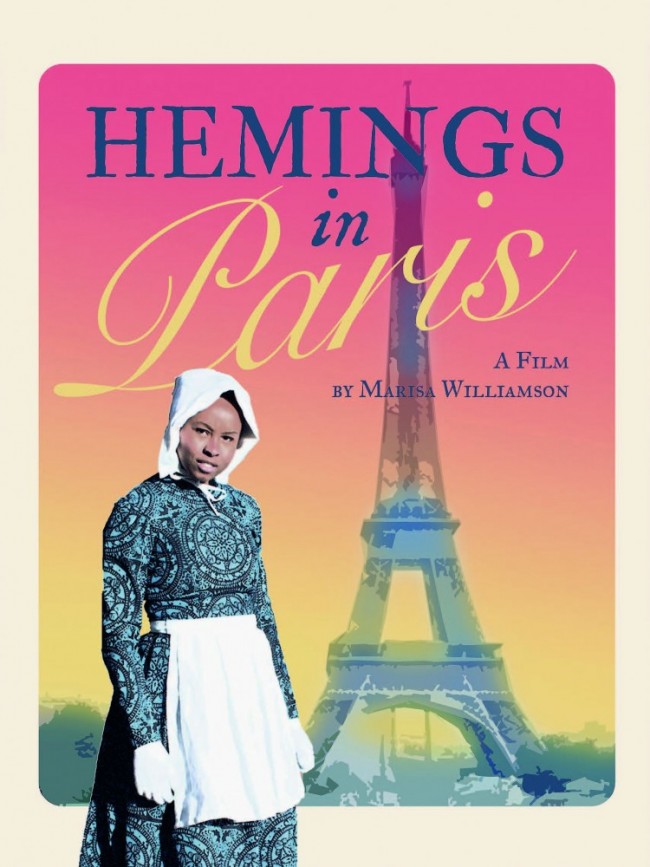

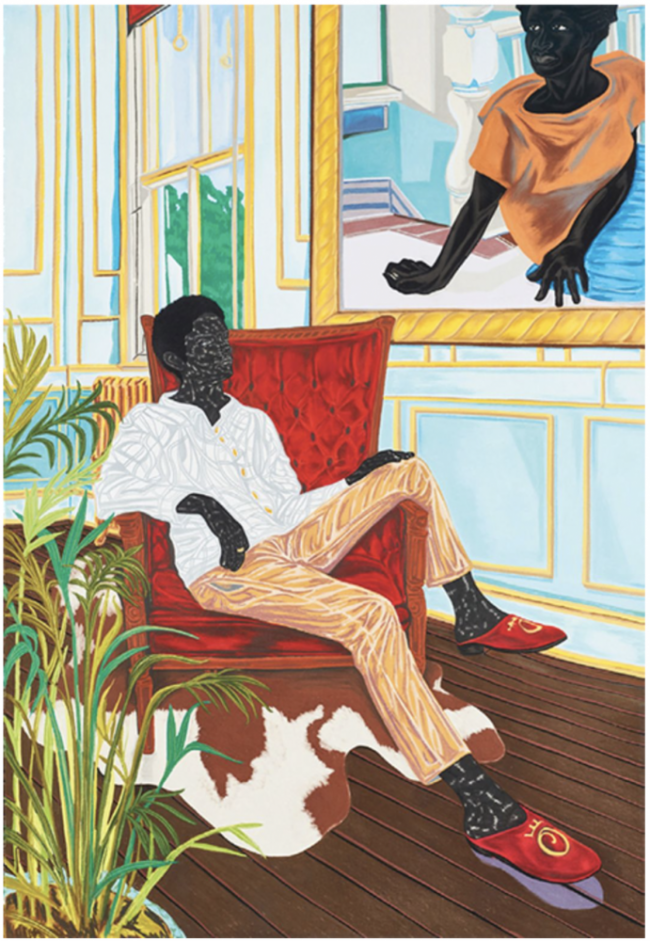

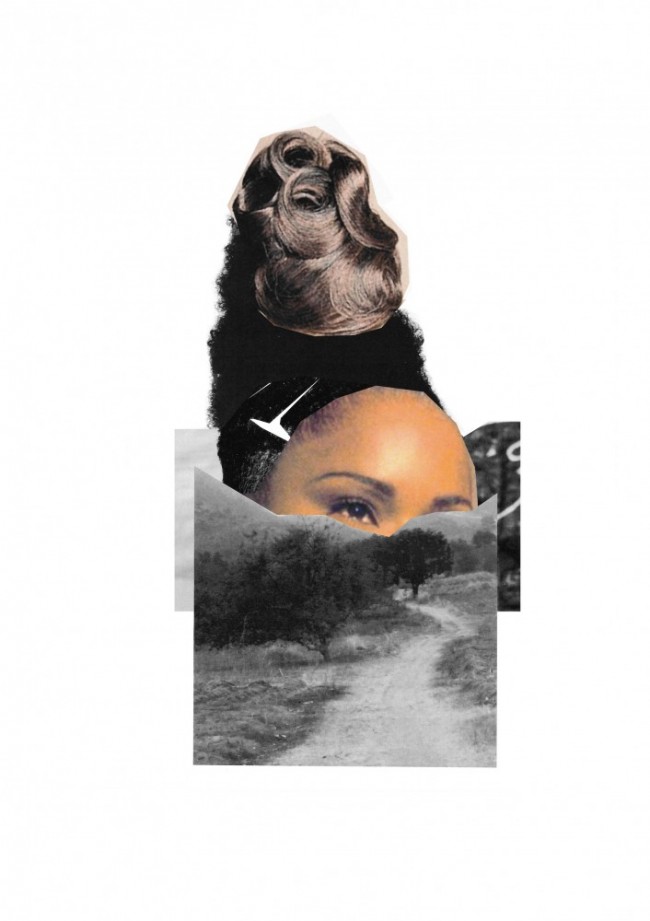

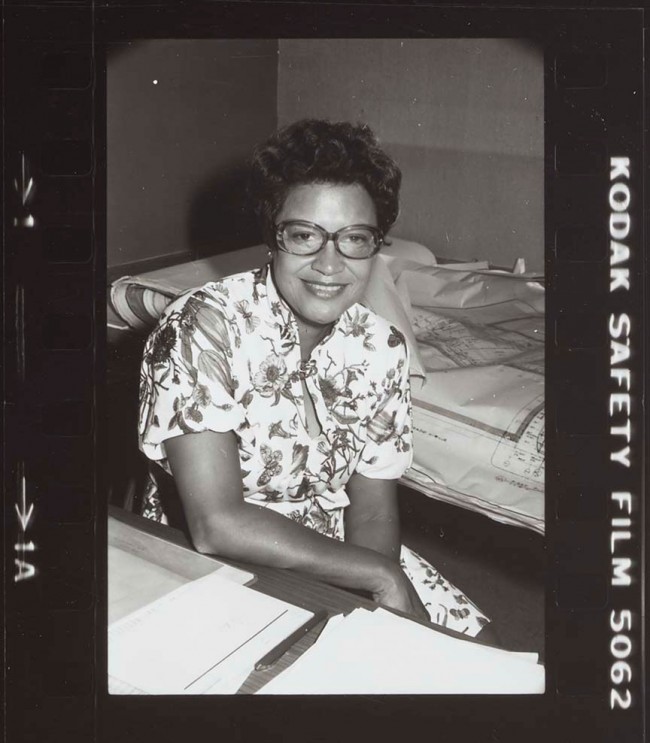

With a background in architecture, Chicago-based Amanda Williams uses art to expose and complicate entangled architectural, urban, political, and economic realities. Working across media — from photography and cut paper to sculpture, installation, and even, i**n her 2014–16 Color(ed) Theory, painting entire vacant homes — Williams challenges racialized and gendered notions of citizenship and safety while begging formal questions of color, space, and movement.**

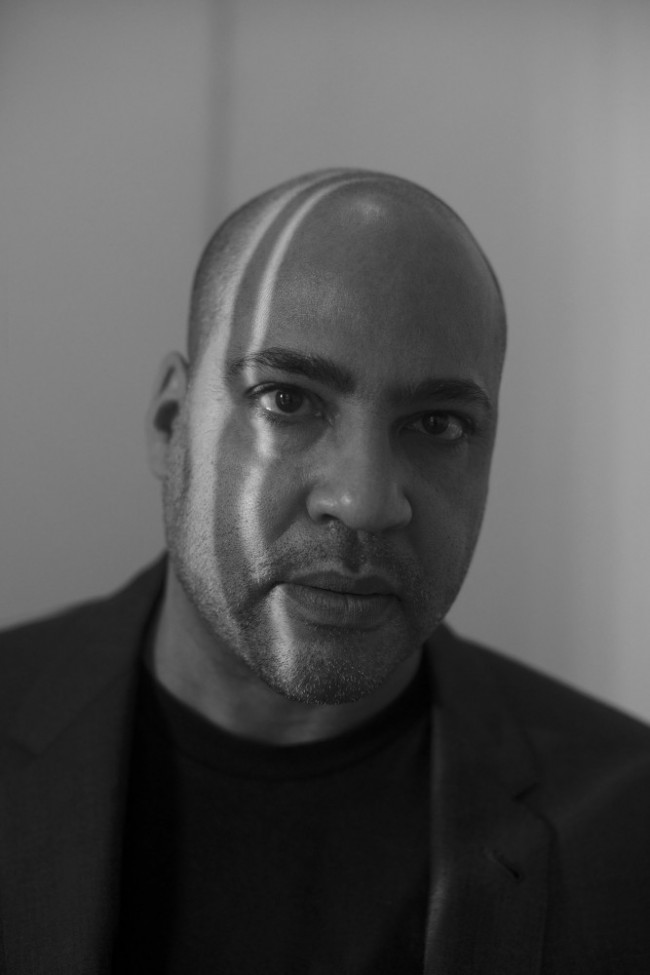

Amanda Williams photographed by David Hartt for PIN–UP.

PIN–UP: What led you to architecture?

Amanda Williams: What brought me to architecture was segregation — the inequities and proactive government policies that denied the distribution of resources for land and home ownership and maintenance and care for spaces, which I traversed while growing up in Chicago. This led to the well-intended but naïve assumption that “architecture” was my path to beauty and equity for these urban landscapes. In fact, what I’m passionate about is space both physical and conceptual — primarily spaces that look like the one I grew up in, no matter the city.

What does that look like in your practice today?

There is pressure in the discipline of architecture to lead with a narrative about “fixing.” Analysis, assessment, site plans from a 10,000-foot bird’s-eye view, funneling “solutions” into form. But why is a project brief so often framed as a problem? What if it was seen through a lens of possibility? Which is not to say through myopic blinders that pretend the slate is blank, but something else, a new model. I have no idea what that is, but that’s the question I’m excited about. My artistic trajectory essentially allows me to iteratively practice in public. There’s a power to ruminating on ongoing themes but framed via different media, scales, and contexts. It’s the throughline that ties “thrival” to Shirley Chisholm (the first African-American woman elected to the United States Congress, to whom Williams and Olalekan Jeyifous are creating a 40-foot monument in Brooklyn) to MoMA to Color(ed) Theory to abstract painting. This approach allows me to create or participate in different projects that can be used to complicate how we map urban/architectural/legal pasts and presents. A creative practice that uses any medium necessary doesn’t take up questions of art or architecture or policy or painting or, or, or… Those boundaries and categories are for someone else. It’s made me tired to parse how much of me is Black or woman or Chicagoan or, or, or... I used to do it out of politeness. I don’t anymore. The same holds true for the work I do. I am compelled by slippages and dualities in our use of and understanding of the language of space — free space, outer space, inner space, physical space. Freedom to, not freedom from. I’m not sure I’ve ever really seen that play out for Black people at a large sustainable urban or even rural scale, but that’s the desire. And I’m asking how I can contribute to all those people using their talent and creativity to get there. Artists, entertainers, writers, policymakers, musicians, intellectuals, my cousin. Anybody.

How do notions of citizenship and public space figure in your practice?

Questions of citizenship and civic space naturally arise as themes in my work because that’s where we see the dissonance and, of late, the friction when it comes to autonomy over one’s right to occupy whatever space or ideology one chooses. Even if you don’t understand the violence inherent in the Constitution, you can visibly comprehend these racial, political, and legal inequities playing themselves out in cities across the U.S. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s voicing of the term “intersectionality” is no longer abstract. The connection between the threads of this wicked problem — race, class, gender, health, zip code, etc. — are impossible to miss.

Can you describe the project you are creating in response to the MoMA Reconstructions brief? Where is it and why did you choose that location?

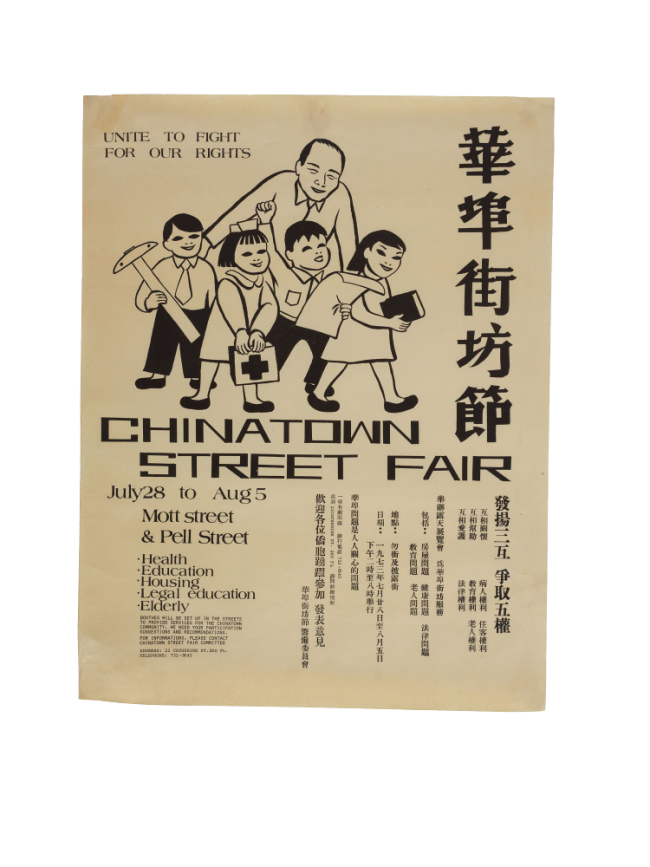

Reconstructions of course allows us to revisit the Reconstruction era in American history as perhaps such a moment to answer or at least ask the questions I’ve laid out. So, beginning with more cursory questions of just “space,” my project thinks about all the tools and fragments Black people might use to navigate their way to free space, which maybe is some extreme physical condition — the open sea, outer space, or Kinloch, Missouri’s first all-Black incorporated town. My project imagines how all of these sites are intertwined, and provides fragments of things I am using to make a new kind of map for hopefully a new kind of world. With that world I can talk about buildings. For now I’ve written prosaic directions to (free) Black space and, and, and...

Interview by Drew Zeiba

Video portrait by David Hartt

Editing by Jessica Lin

Music by King Britt presents Moksha Black

A PIN–UP production in partnership with Thom Browne

This video is part of a series of ten portraits David Hartt created for PIN–UP on the occasion of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America at the Museum of Art (Feb 20–May 31, 2021), curated by Mabel O. Wilson and Sean Anderson. The portraits were also published in the print edition of PIN–UP 29.