BOOK CLUB: In Search Of African American Space

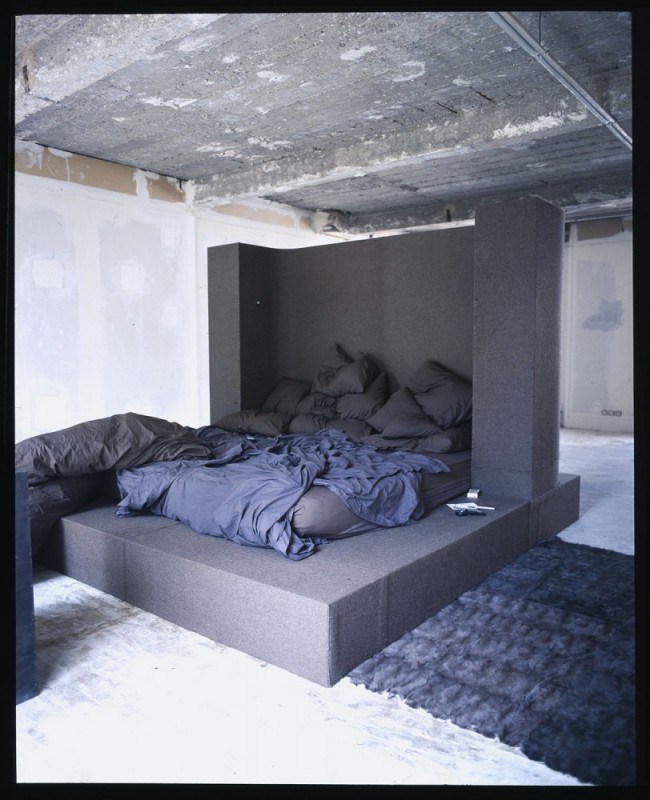

Taking up the challenge of defining African American space is rife with complexities. The very notion of space can range from the personal — issues of self-determination and how we allow ourselves take up space — to the political — excavating the contemporary legacies of slavery, and the built environment necessary for its sustenance. Amidst an increasingly global confrontation with racial injustice, the need to create spaces conducive to radical imagination, healing, and restoration for Black people is ever-so important. Speaking to the urgency of this moment comes In Search of African American Space, a new anthology edited by Jeffrey Hogrefe and Scott Ruff with Carrie Eastman and Ashley Simone.

Door of No Return, part of the House of Slaves museum and monument in Gorée Island, Senegal. © Rodney Leon / Rodney Leon Architects

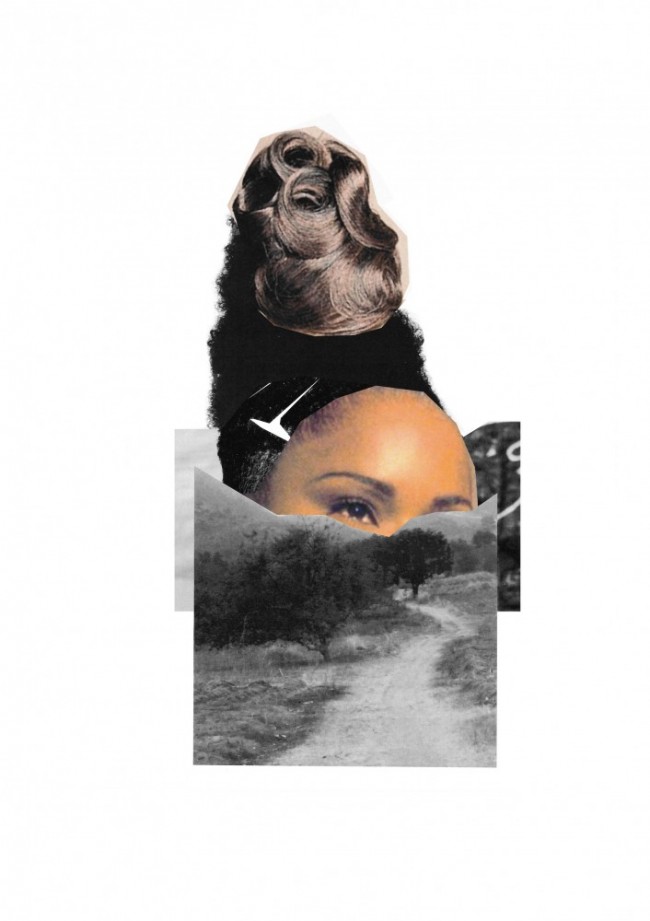

Rather than seeking to define a singular African-American space, the book seeks to represent the abundance of ways in which it might exist, approaching this inquisition via three distinct but interrelated sections: “discourse,” “production,” and “artist practices.” A diversity of voices — architects, historians, and artists — offer up their unique understandings of space, allowing personal reflections to strengthen collective pursuits. Examining issues of representation, the public performance of sociability, and the relationship between architecture and African American identity, the book reads as a poignant, necessary, and generous attempt to outline spaces that are defined by, but not limited to various axes of oppression.

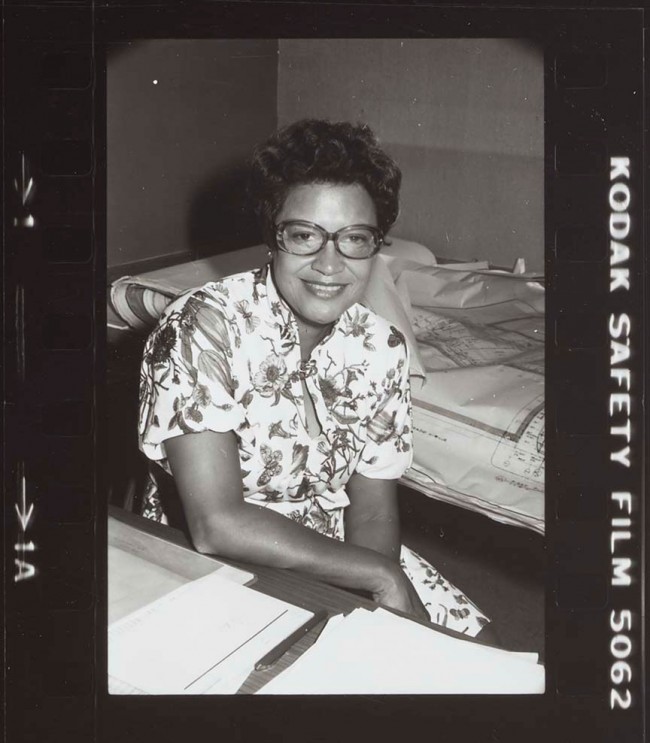

J. Yolande Daniels, architect and member of the Black Reconstruction Collective, pens a brilliant essay describing “negative monumentalization”. She describes this as an act of monumentalizing through the absence of historical narratives, akin to Saidiya Hartman’s methodology of “critical fabulation” — which seeks to give voice to those traditionally omitted from historical archives of trans-atlantic slavery. Daniels frames this concept with her descriptions of Casa dos Contos, a present-day museum in Ouro Preto, Brazil, built to preserve the history of the nation’s gold rush. Despite the building currently operating as a monument, its previous housings of enslaved persons — as evidenced by the slave quarters still present in the basement — are not acknowledged by the museum, as it provides no information to address this history. Daniels recalls her emotional response to a space that is at once visible and invisible, her thorough descriptions of these quarters creating a record of these events that remain otherwise unaddressed.

View of corner projection installation of Yolande Daniels’s Silent Witness, in Casa Dos Contos, Brazil, 2001. © Yolande Daniels

In a previous chapter, Elizabeth J. Kennedy, a landscape architect for the Weeksville Heritage Center in Brooklyn, shares a similar sentiment concerning the resurrection of expunged histories. The historical community of Weeksville, founded in 1838, was made up of previously enslaved persons and was one of the first free Black communities in the United States. Kennedy describes how the landscaping of the center sought to rediscover the historical farm grids that had been lost, choreographing the topology in opposition to the city grid. These accounts help illuminate how African American space is characterized by the need to discover what has been lost, or forcibly erased. To search for African American space is to commemorate a silenced history amidst residual struggles. It’s a resilient practice.

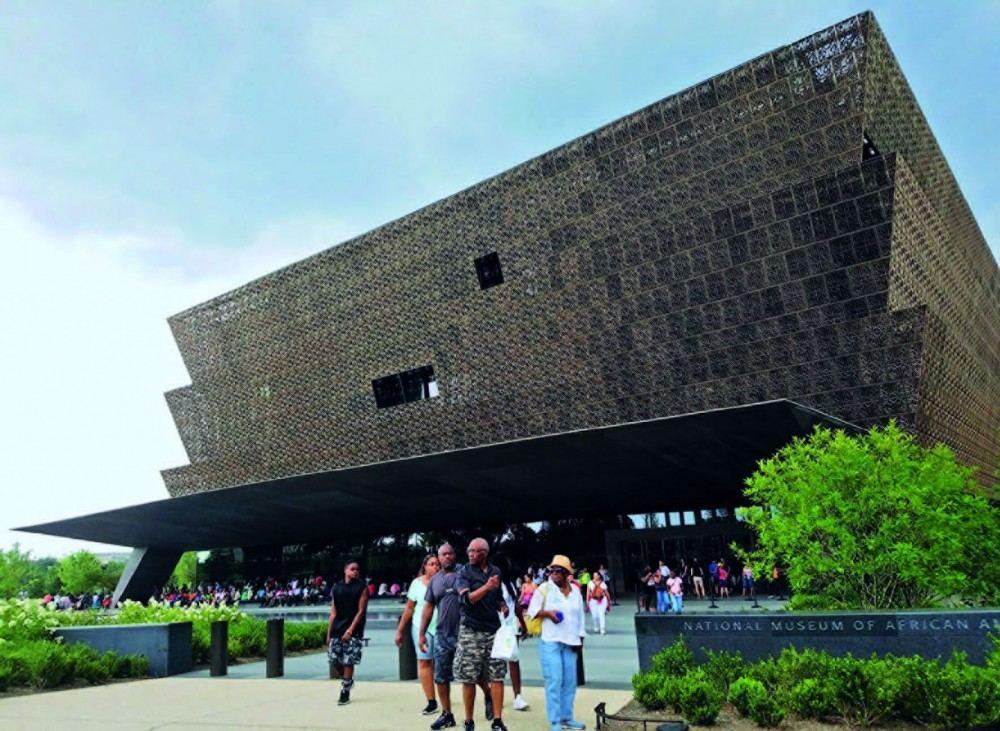

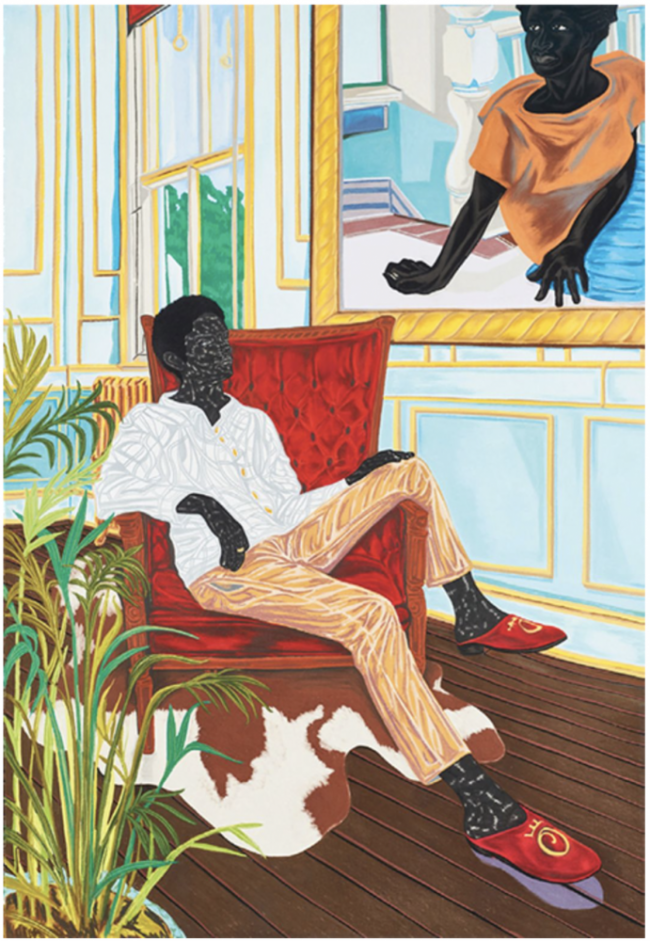

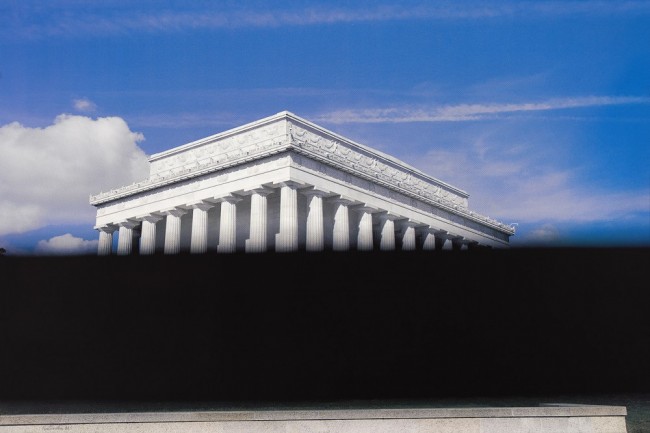

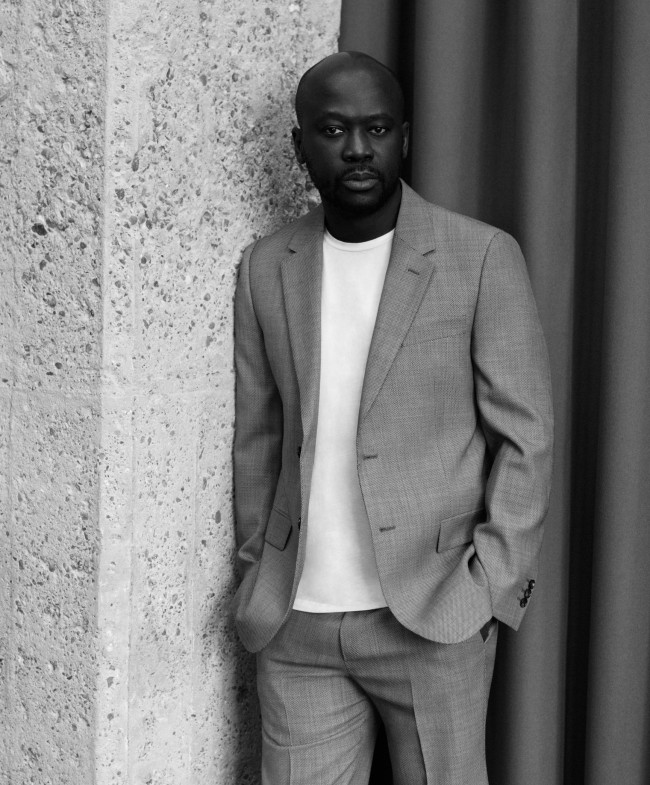

Perhaps the most iconic manifestation of an identifiable African American space is the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), designed by architects David Adjaye, and the late Philip Freelon. In his essay, Scott Ruff, principal of RuffWorks Studio, addresses the various references in the building’s design, examining the structure through DuBois’s theory of double consciousness, amongst other lenses. In doing so, Ruff presents a convincing description of the paradoxical spatial conditions present at the NMAAHC. The building, sited next door to The Washington Monument, is a necessary reminder of the cultural resiliency of Black Americans. However, as Ruff writes, its formal and material contrast with its neoclassical neighbors highlights the “culture of separateness” visible in other traditionally African American spaces such as the plantation quarters, and the ghetto. The construction of African American identity in opposition to its oppressive forces is present in the visual language of the museum — echoing DuBois’s theory that how Black people see themselves is shaped by how they are viewed by a predominantly white, racist society. Ruff’s essay reveals how African American space is undoubtedly informed by social constructs that regulate the Black body in America.

-

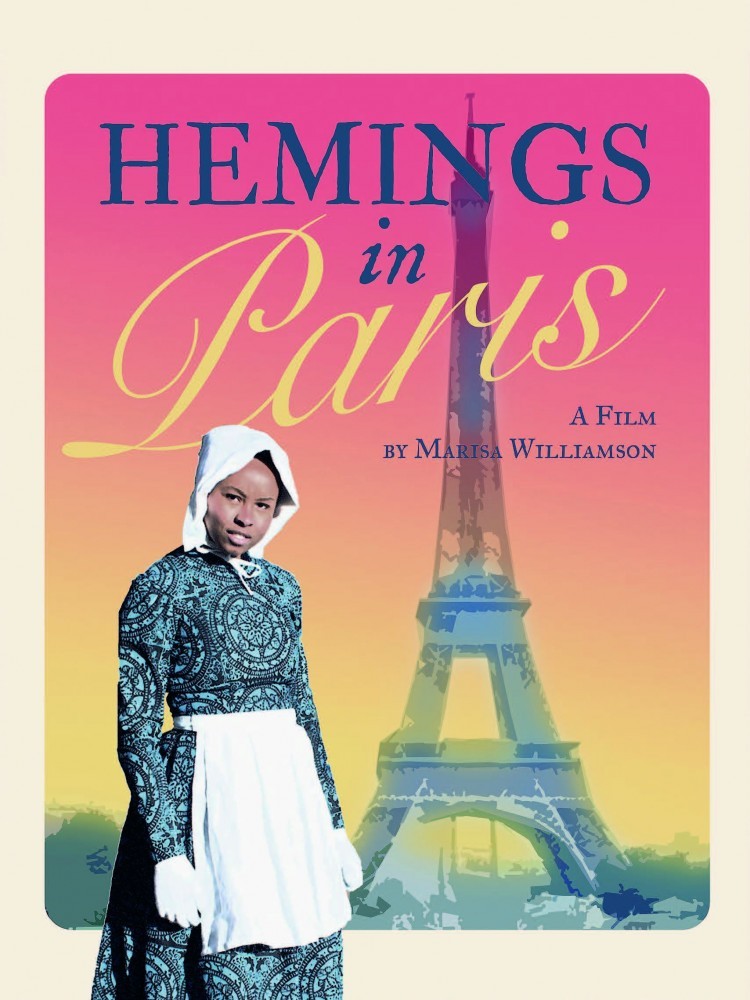

Poster for Marisa Williamson’s film Hemings in Paris, 2004. © Marisa Williamson

-

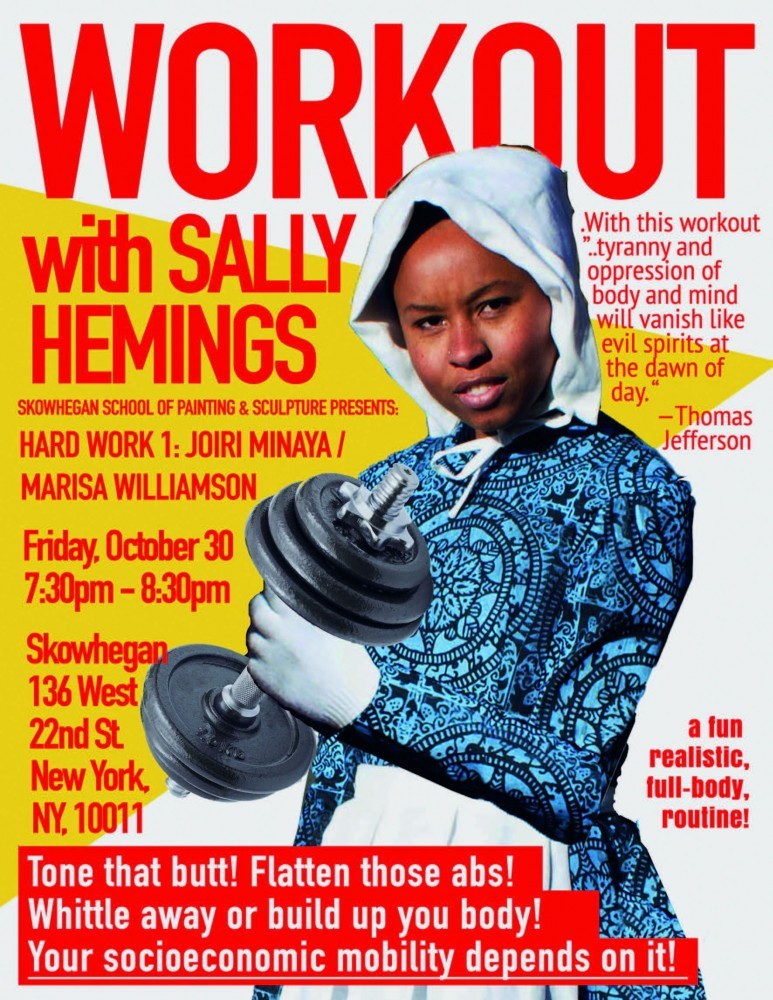

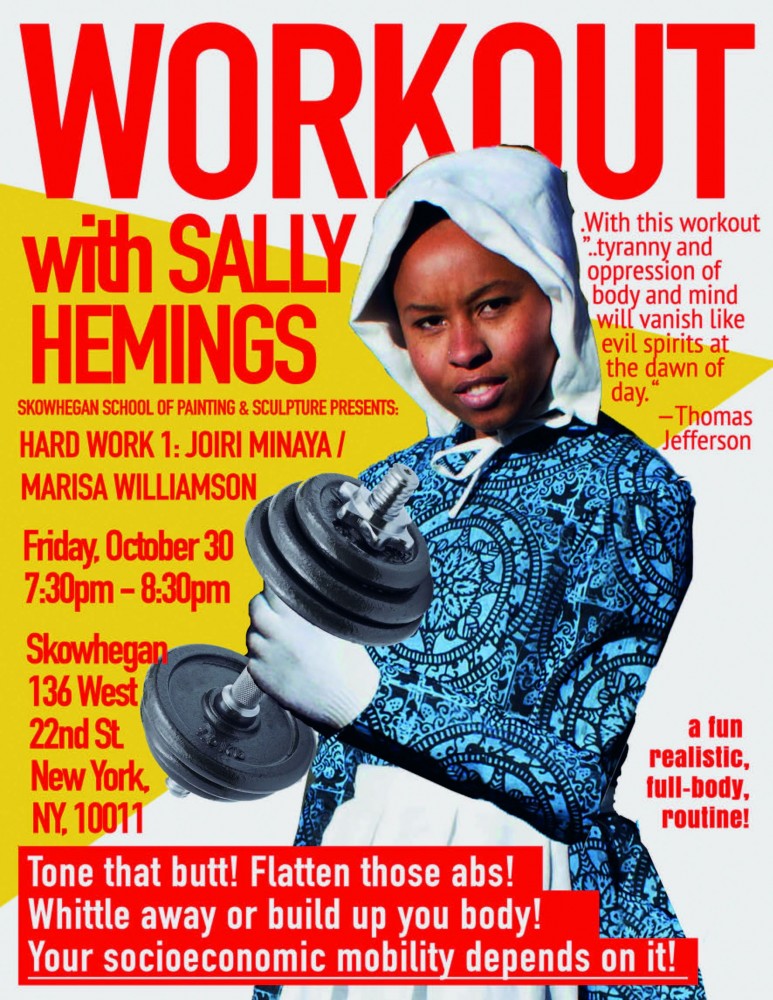

Poster promoting Marisa Williamson’s Workout with Sally Hemings at Skowhegan Headquarters, New York, 2015. © Marisa Williamson

The book is diligent in its approach. From the onset, it establishes a clear grammatical style, outlining the importance of the capitalization of “B” in Black, and the use of “self-emancipated person” as opposed to “runaway slave.” The care exemplified in seemingly minimal grammatical choices is representative of the effort taken to craft a volume that contributes to the fight for liberation.

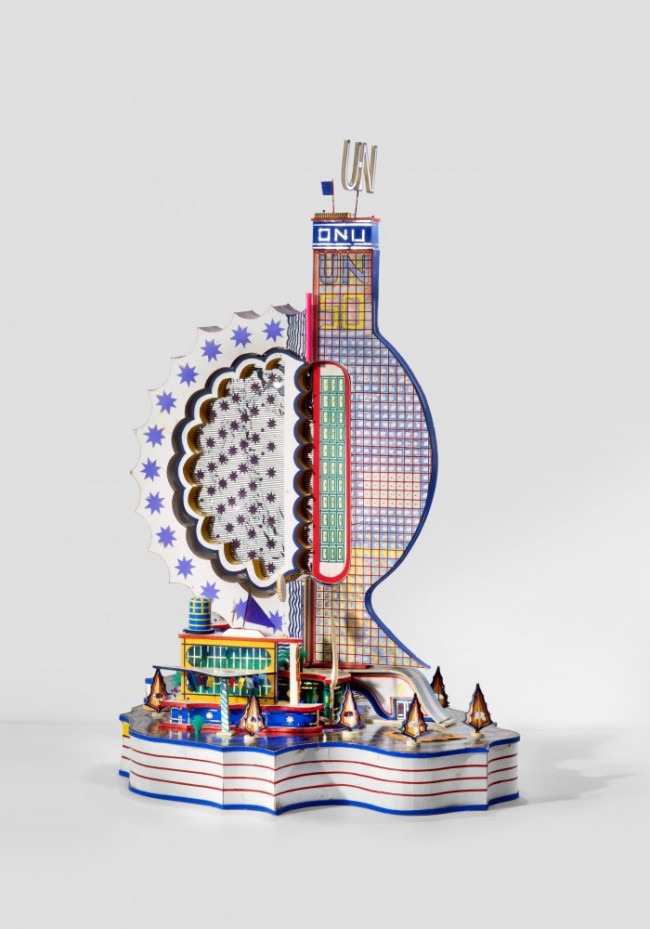

At multiple points in the book, the interconnectedness of African American space and African symbolism is illustrated. From the “African” references of the NMAAHC’s façade to the “African” symbols deployed on the walls of the African Burial Ground Memorial, African American space, while inherently American, can not exist apart from its diasporic history. However, concepts of space that relate to the African origins of African Americans seem to be merely referential. This is less of a critique against the volume, and more a caution against symbolic representations of the extensive visual cultures present on the African continent. Although perhaps this is an inescapable condition of the works created by a people ripped from their origins, denied cultural subjectivity, and then placed in a land reliant on their suppression.

Text by Oluwatobiloba Ajayi.

In Search of African American Space edited by Jeffrey Hogrefe and Scott Ruff with Carrie Eastman and Ashley Simone (Lars Müller Publishers, 2020).