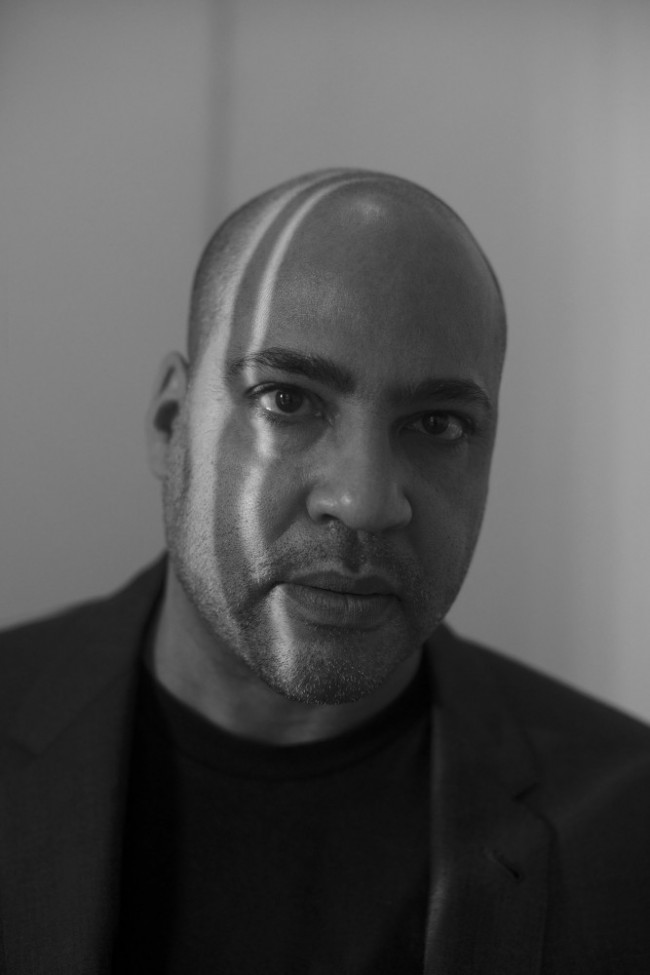

INTERVIEW: Isaac Julien on Architecture and Performance

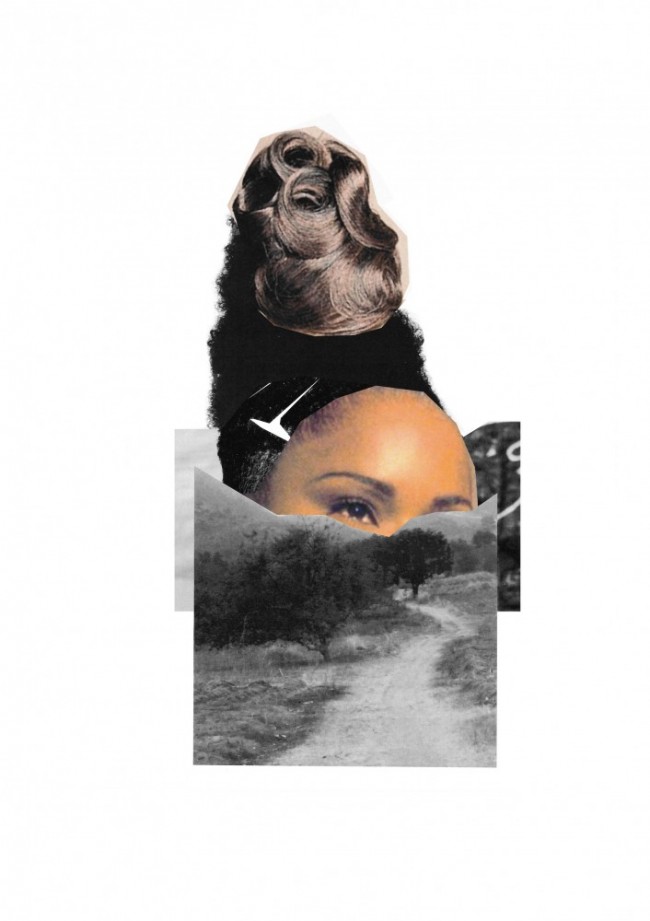

Isaac Julien, Sem começo nem fim / Without Beginning or End (Lina Bo Bardi – A Marvellous Entanglement), 2019. Endura Ultra photograph face-mounted. © Isaac Julien. Courtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco

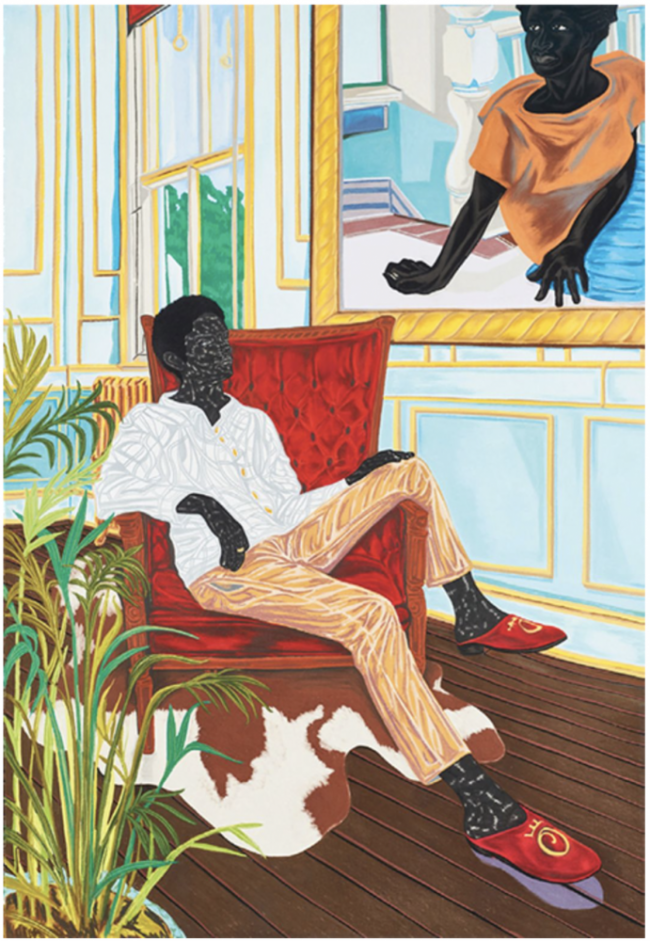

London-born, now California-based artist and filmmaker Isaac Julien is known for his sweeping, lyrical films, often fanning across multi-screen installations to bring historical narratives into physical space. His early work explored the fraught confluence of race and art, such as a breakthrough piece on the erotics of Langston Hughes. Recent projects have turned to architecture, a cinematic treatment of how bodies move through built space, like 2014’s Playtime, where, among other backstage glimpses of the contemporary art market, a domestic servant gazes out the window of a high-altitude Dubai apartment. Architecture itself stars in Julien’s most recent work, Lina Bo Bardi: A Marvellous Entanglement, shown in Rome in 2019 and now enjoying its U.S. debut at the Bechtler Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina. The 40-minute film explores several major projects in Brazil by the Italian architect, activating her idiosyncratic, innovative spaces through dance and theater, as well as cinema itself — the work flashes between nine screens, installed in the museum on square block plinths that mimic the easels supporting paintings in Bo Bardi’s São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP). As with Bo Bardi’s public buildings, there’s a certain rigor to the installation; but also, emphatically, a palpable freedom. The show at the Bechtler Museum closes February 27, 2022.

Travis Diehl: Can you talk a little bit about the installation, the way that you spatialized the film across nine screens, and the way the seating is arranged in the room? How do you imagine the viewer interacting with the piece, or vice versa?

Isaac Julien: I think with artists like myself, who've been involved in the aesthetics of multiple screen installations for some time, you begin to develop theories along with curators that you work with. Just to go back a little bit, when I had a show at the Pompidou in 2005, I made a four-screen work called Phantôme Créole. The idea was that the screens would be placed around the perimeter of the room and the spectator would walk into it, and then they would be able to participate a bit like an editor of the work by turning around. But then all that happened is that when we put beanbag chairs in the middle of the space, people dragged them to the far corner of the room where they could view all the screens. So that failed. With A Marvelous Entanglement, it’s obvious that you can view it from different positions because the seating is arranged in that capacity. The work can be a bit disorienting when you first walk into it because the nine screens do switch off, and the sound guides you as well. There’s a north-south, west-east movement to the screens. I’ve constructed the sweet spot, of course — you can look at the piece in its entirety, but then, you don't necessarily have to. People can have an ambulatory relationship to the work, then dive out of it. But people do tend to stay to see a whole cycle, and they recognize the point of the sequence where they came in. Of course, there is a kind of beginning and an end to the work.

I wanted to ask about that moment, which maybe is the end, where the director of the Teatro Oficina, Zé Celso, is instructing one of your Lina Bo Bardi characters. You see a cameraperson in the shot, and the actors are addressing the camera directly. Why reveal the artifice?

A lot of my work reveals the fourth wall, so to speak. To be frank, in this part of the film, everything slightly breaks down. It's the moment where Fernanda Montenegro is reciting one of the many manifestos of Lina Bo Bardi. It contains the title of the film, A Marvelous Entanglement. “Linear time is a Western invention. The time is not linear. It’s a marvelous entanglement where any permanent points can be chosen, and solutions invented without beginning or end.” There’s a kind of playful deconstruction of the work.

How do you reconcile the fact that video and film are linear media—you're making a linear work about non-linear time?

One of the reasons why we watch films per se is the comfort that there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end, or some kind of resolution. But within the nine-screen work, the poetics of viewing or the poetics of the attention that one can give to the work becomes where one is able to disrupt that question of linearity.

You also have two actors playing Lina Bo Bardi.

Yeah. Fernanda Montenegro is a little bit like the Greta Garbo of Brazilian cinema, and Fernanda Torres is her daughter. In their performances, you get that mirroring of actions and manifestos and texts being spoken sometimes simultaneously by the mature Lina and the younger Lina. And then at the same time, each actor has her own iconicity. That doubling collapses different time periods. The buildings function that way too, because they speak to an earlier moment of brutalist, modernist architecture — they’re mostly made in the sixties through the 1980s, but filmed today.

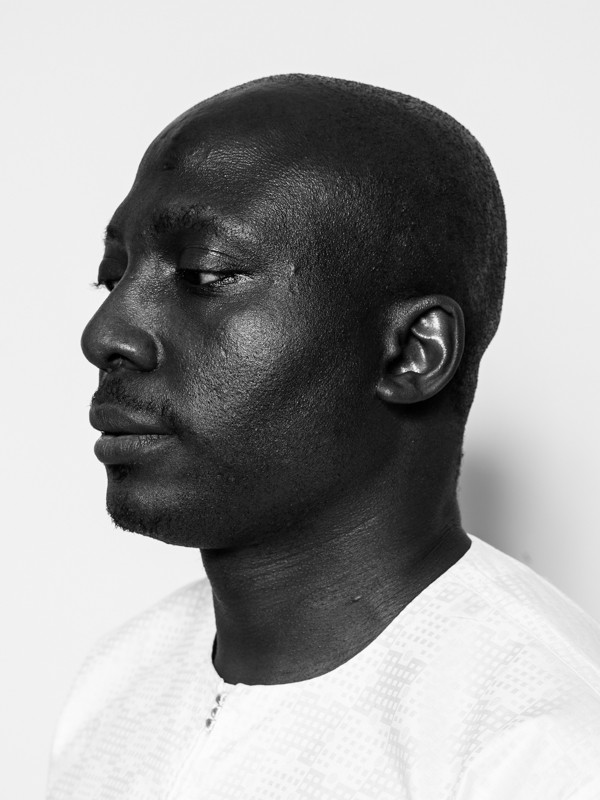

Isaac Julien, Lina Bo Bardi – A Marvellous Entanglement, 2019. Nine-screen installation, super-high definition, colour, 9.1 surround sound. 39 min 08 sec. © Isaac Julien, courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Nostalgia is maybe a dirty word, but how are you playing with the tendency to romanticize that era of architecture and design?

Well, growing up in London, I wouldn’t say that I'm a fan of brutalist architecture. The Hayward Gallery in the South Bank, for example, people don’t view so convivially. But the way that Latin America interpreted brutalism, the way space is attended to, is I think more playful than the British version, but then that’s made me revalorize the brutalist architecture in Britain as well.

There’s a moment in your film where Bo Bardi is sitting in the theater at SESC Pompéia, discussing the lack of upholstery on the wooden seats, and how theaters didn't have upholstery in ancient Greece and so on, until consumer culture started padding seats to make customers happy. Is there an aspect of that in your installation or in your film?

If you go to SESC Pompéia and see a play on those benches, they're not uncomfortable. Of course, she's a control freak. She's designed every single item from the chairs to the tables. I've tried to mimic the concrete plinths from MASP as seats and as plinths in my installation at the Bechtler. Maybe it could look austere. I think it has a hint of theatricality, a clean-cut sort of architecture and scenography.

It’s also carpeted.

She probably would object to the carpet. Call it a necessary evil, because it cuts out sixty to seventy percent of sound reflection.

In A Marvelous Entanglement, you chose to show and activate public buildings, like the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP) and the SESC Pompéia. Why stick to the public facing version of Bo Bardi’s work?

If you go to São Paulo on the architecture tour, you’re bound to go to Casa de Vidro, the glass house where Bo Bardi lived with her husband. But I chose to concentrate on public spaces, and more to the point to concentrate on spaces which are hard to access, like the Coati in Salvador, which was meant to be an artists’ café but is in a ruined state. If you go to MASP, you see the paintings displayed on the glass easels; if you go to SESC Pompéia, Lina Bo Bardi has turned this kind of factory into a wonderful space for people from many different walks of life. Of course, Oscar Niemeyer designed the whole city of Brasilia, but at the same time, Lina Bo Bardi is antithetical to Oscar Niemeyer. She makes a comment about disliking air conditioning and carpets, which is a bit of a swipe at Niemeyer. She prefers to cut holes in the concrete to solve the question of ventilation in a tropical climate. A lot of her techniques are based on observing the way that working class or peasant culture might produce their answers to architecture.

When the two actors playing Bo Bardi enter the Coati, they seem very distressed.

The work’s original title was The Ghost of Lina Bo Bardi, and when they go to the Coati, let's say that the ghost of Lina Bo Bardi returns to that space. Her time in Salvador was during the fascist dictatorship. Not that I think people would be able to read any of those things, but I think you get the sense that there's something of a disturbance taking place. You could also say that when I was making the work, Jair Bolsonaro, the current president, was also coming into power.

The Bo Bardi character says something to this theme, that artistic freedom is individual freedom, but the only real freedom is collective freedom. I wonder how you think about that statement as an artist and an individual. It seems dense and maybe contradictory, but is maybe why she tried to work through these public buildings.

I think it's exactly that. Architecture demands a certain capital. In terms of making public projects, which is the raison d’être for a lot of architects, you need to persuade, and get a contract with various public bodies, sometimes with the state, or your work's not going to get made. But in a kind of existential philosophical sense, the question of autonomy in the culture is granted by the state. Because, if we take up what's happening in China, or in Hong Kong in particular, in terms of films, now a certain censorship has been applied. So, there you have it.

Do you feel free as an artist?

I mean, all artists are free, within certain constraints. I didn't suffer from any censorious activity. But it did take me four years to gain access to the Coati.

Interview by Travis Diehl

All images courtesy Isaac Julien and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.