INTERVIEW: Ibiye Camp On Her Hyrbid Practice Materializing Data And Mapping Public Space

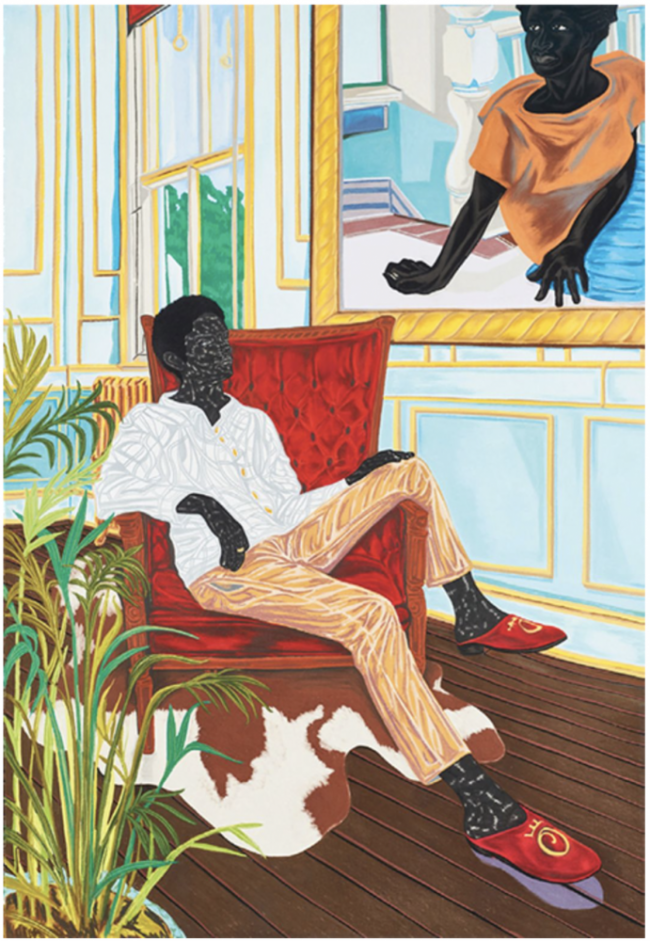

Ibiye Camp is an artist, architect, and fashion designer living between London and Freetown, Sierra Leone. Camp is rethinking the role of postcoloniality and technology in the built environment. For her recent project, Data: the New Black Gold, 2019, she used a prototype of a mobile smartphone mount she invented, dubbed Area Snap, to gather user-generated data on markets in Nigeria and Sierra Leone. Through her project, intricate details of market infrastructure and activities — like where mangos are being sold on the street and how many mannequins are outside a shop, the location of generators, seating, shop signage, or vendors’ pushcarts — all become part of a new virtual vision of the urban landscape. Camp explains that this data materializes, “an imperfect digital city, built on principles that oppose western architectural ideals of modeling.” The future of public space is central to Camp’s practice. Another example is a collaboration with Emmy Bacharach and David Killingsworth, a project commissioned for the 2019 Sharjah Architecture Triennial, The Sacred Forests of Ethiopia, which considered the sacred church forests of Amahara, Ethiopia as sites of spiritual and environmental resistance. Camp spoke with PIN–UP about reimagining urban space and ecological design, as well as the role technology can play in empowering citizens to take control of their own environment.

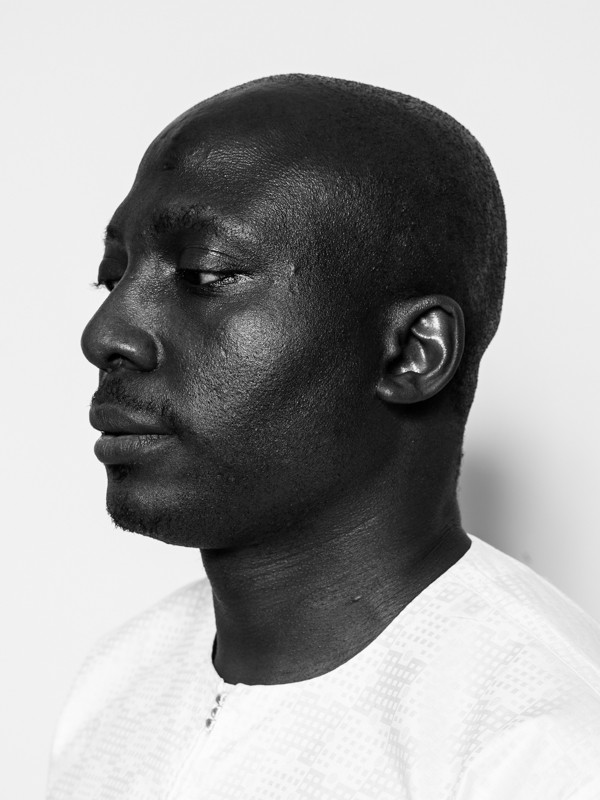

Ibiye Camp photographed by Duval Timothy.

Jareh Das: You are an artist, architect, researcher, and fashion designer. How has working across disciplines foregrounded your relationship to and engagement with space?

Ibiye Camp: Like many, I’ve had to insert myself into spaces, whether it was within an artistic field, institution, or moving between the spaces of being British-Nigerian. My interests have always been broad: fashion, product design, storytelling, painting. I’ve tried many artistic fields, seeking access to spaces and to knowledge systems. There is a pattern in my practice in distributing spaces and the tension within the landscape. I use architecture to intervene with space whether it is to disrupt space with color, or using augmented reality to reveal alternative spaces and narratives.

At the beginning of my studies, I would curate performances to play on the engagement and participation of the audience. This led to questions about the role of the performers within a space, the actors in a space or event. As a child I would visit my family in Buguma, River State, Nigeria. In Buguma we would attend masquerade performances which come from a cycle that takes seventeen years to complete. The masquerades are performed by The Kalabri Ekine Sekiapu Cultural Society, which consists of only males. Women watch the performance but they are not supposed to know the secrets of the all-male Sekiapu Society. This performance was a reenactment or a form of storytelling from the gods of the rivers. The audience are the observers but also a crucial part of the ceremony.

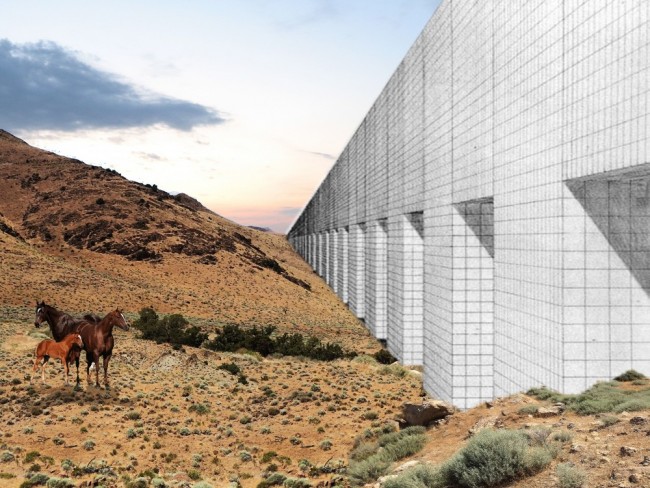

3D-printed model of Campbell Street in Freetown, Sierra Leone (2019).

I got to know more about your architectural practice when we met at Venice in 2019 and I visited your RCA graduation show that summer. I was struck by your project Data: the New Black Gold (2019) and your focus on data as a new form of currency as opposed to numerous material extractions — oil, copper, diamonds, etc. — on the continent. What does data as architecture mean to you and what informed your research into comparing data economies and the history of oil extraction in Nigeria?

The architecture of data is a fundamental component of today’s political, cultural, and socio-economic landscape. The Submarine Cable System that connects Africa to the rest of the world via Europe highlighted the imperialism of data infrastructure. Today there are six individual cable systems off the coast of West Africa and the largest provider of the fiber optic cables is called MainOne. This is one of the networks that travels from Amsterdam, through London and then to a landing point in Lagos. As you probably know, Lagos is the current largest data economy of West Africa.

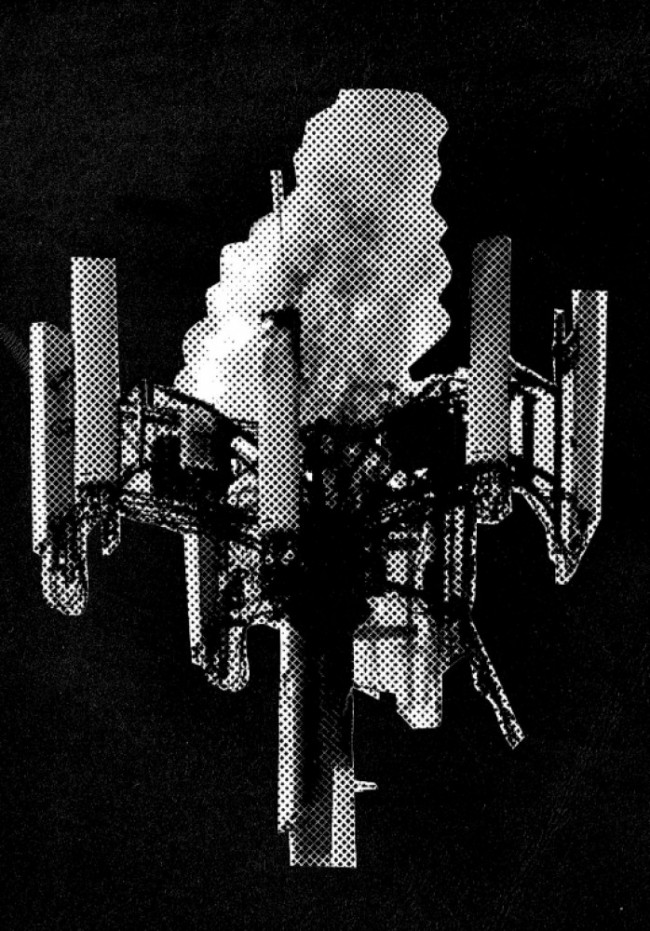

Data has become the world’s most valuable resource whereas a century ago, the most valuable resource was oil. My project Data: the New Black Gold comments on the history of crude oil being deemed Nigeria’s “Black Gold.” The oil sector and digital sectors are similar in the violence of their infrastructures and the input of multinational corporations within the landscape which disregard the citizens who reside there. Recently I have been questioning digital and physical infrastructures, thinking through how data can take up space — whether as a data center, home hard-drives, or even people themselves. I have been cross-examining the various digital infrastructures that have been implemented or extracted from the landscape. Working across these multiple mediums, the architecture of data is in a microscopic scale of fibers, fabric, waste, minerals and then at a trans-national scale of extractive trade and global infrastructures.

Data: the New Black Gold also points to a democratization of data as currency that citizens mine and own. Is this emphasis on making visible the invisibility of data architecture to citizens a way to counteract and challenge the current norm of surveillance capitalism and corporations monopolizing the collection of data?

Exactly, it is about restitution of ownership. In the past the Nigerian government has not held major corporations accountable for their oil or data leaks; however, similar actions of citizens are automatically deemed vandalism and criminal. This imbalance exacerbates the gap between international companies and the local population. Data: The New Black Gold explores how citizens could take ownership of the data generated from their cities, during this time of technological investments and developments from overseas. The project highlights the biases and conflicts of data consumption and the tensions between government, private corporations, and citizens. Lagos is the most densely populated city in Africa. If resident data collection became a trade within the city, the effect could counteract the multinational corporations’ control and plans for landscape and mega city plans.

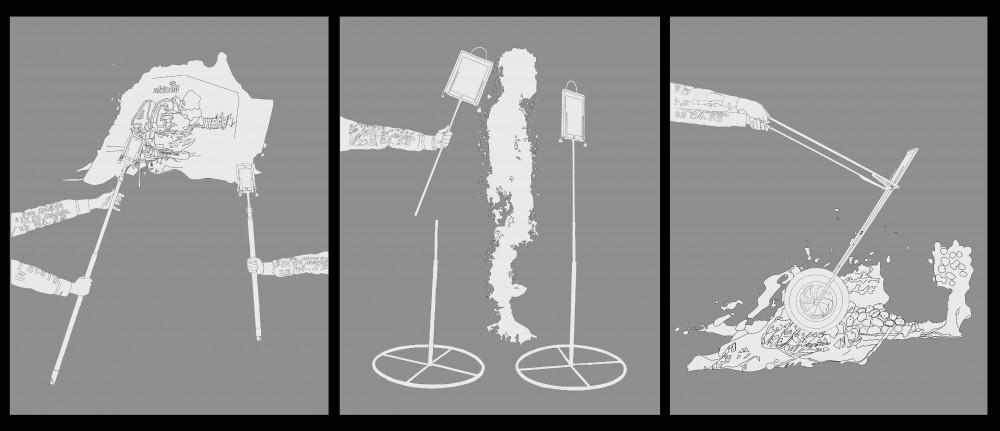

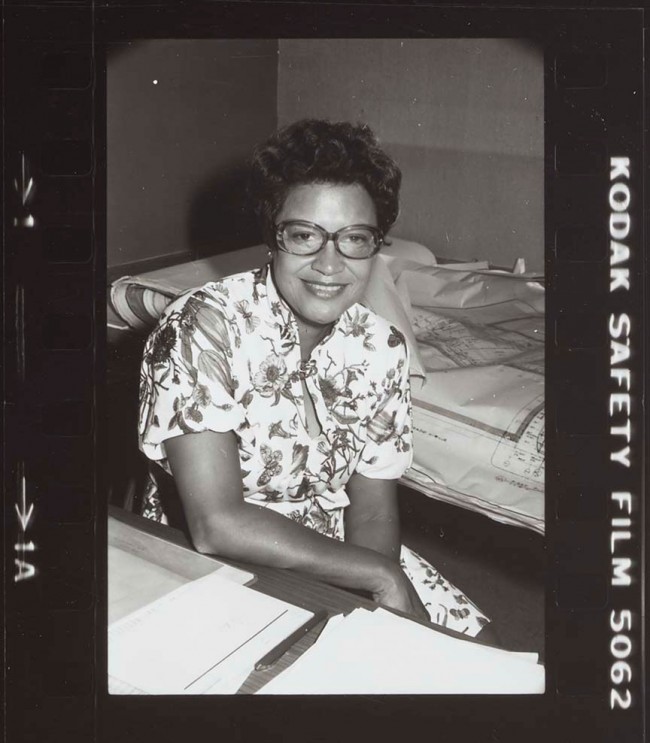

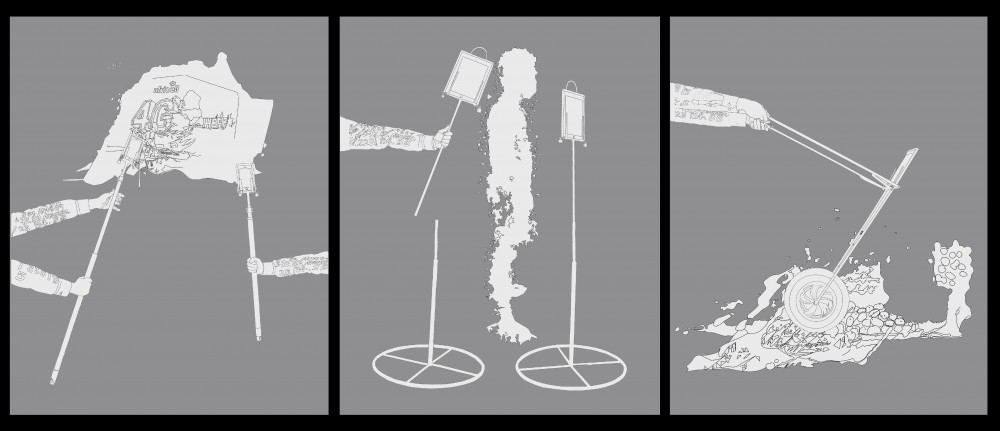

Ibiye Camp’s Area Snap devices collect data from different perspectives (from left to right): bird’s eye view or flying witch; eye view or walking and spinning; and ground view or detective wheelbarrow.

How did your research process unfold in Lagos and Freetown, and what informed creating the mobile data collection tool, Area Snap, as a method for data collection?

In 2018 I traveled to Nigeria and Sierra Leone where I explored some of the most historic markets and spaces of trade. In Lagos, I visited Balogun Market, on Lagos Island. Whilst in Freetown, I went to Malamah Thomas Street market which is also known as “lapa street.” As I was working from references from these two countries, I sampled language and tools that were used by the vendors in the markets. As this project was a prototype, I initially collected all the data with Area Snap devices I had designed myself, but I discovered it was more effective if I handed this task over to vendors so that they were able to collect the data whilst carrying on with their regular everyday routines in the market. The Area Snap devices work by collecting data from three viewpoints: the ground view, Luk-grnod-man omolanke, which means “detective” in Sierra Leonean Krio, but also is a push cart or wheelbarrow in Nigerian Pidgin; eye view, Waka turnturn — walking and spinning in Sierra Leonean Krio; and the bird’s-eye view, Air Force 1, which refers to a flying witch in Nigerian Pidgin. In designing the Area Snap devices, I sampled elements of the designs that the vendors had assembled. The added details were mainly to make the devices mobile and adjustable. They are basic, practical, and efficient devices.

Curator Legacy Russell argues in Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto that “the ongoing presence of the glitch generates a welcome and protected space in which to innovate and experiment.” I feel this idea of the glitch — which usually refers most specifically to unintentional disruptions in digital technology — really embodies working with the unpredictability of public spaces like Lagos or Freetown markets, which can be more informal spaces. The field of architecture is often seen as one based around detailed planning and very structured ideas. How might the glitch upend traditional understandings of architecture?

I see the glitch as a form of resistance and therefore a space to design within. The photogrammetry process is unpredictable in live spaces. Documenting Balogun market, for example, exposed inefficient or ineffective aspects of the technology, like the difficulty of reading space that has movement or a variety of textures. Documenting in this way in the heart of Lagos Island demonstrated how notoriously difficult it is to capture scenes and objects that are black, shiny, moving, have large sun exposure or, in contrast, heavy shadows. The produced point cloud created in Balogun market revealed errors and only captured a trace or ghost scan of the market. Live spaces create material resistances and exacerbate glitches in technology. The glitch is embedded inequality in how technology works in identifying texture, color, materials, and time. The dynamics of technological glitches of data exposed the conflicts of digital infrastructure in the landscapes, which questions the disconnect of technology to the reality of the landscape. The movement where a glitch happens allows multiple realities and scenarios to be designed or speculated within.

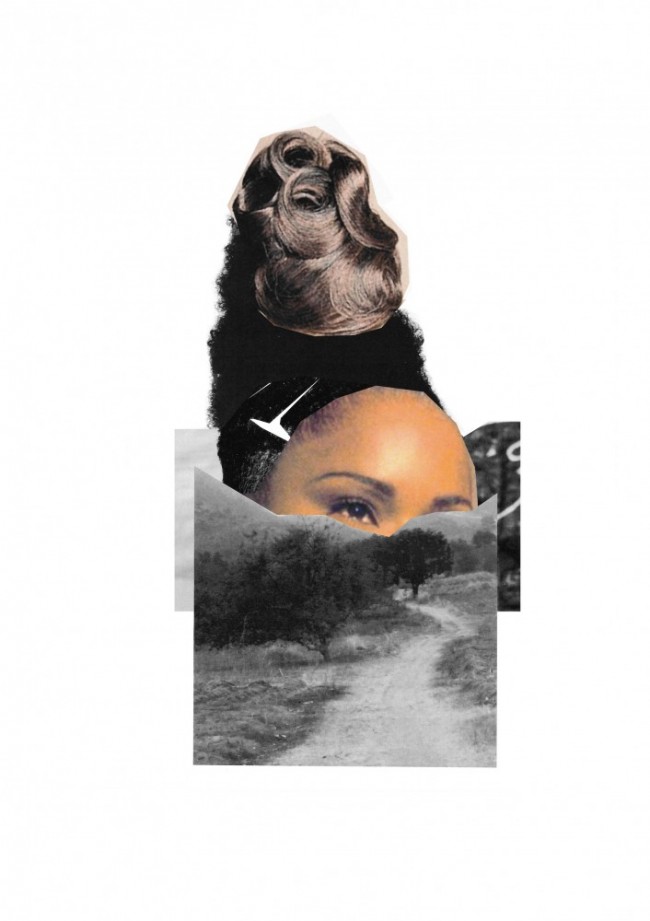

Installation view of Sacred Forests of Ethiopia by Ibiye Camp with Emmy Bacharach and David Killingsworth, commissioned for the 2019 Sharjah Architecture Triennale. Photography by Matthew Twadell.

For the 2019 Sharjah Triennial, you presented The Sacred Forests of Ethiopia a collaboration with Emmy Bacharach and David Killingsworth. In it you considered Ethiopia’s sacred forest believed to provide protective “clothing” for sacred spaces and communal uses as well as much needed shade for miles. What first sparked your interest in looking at these sacred sites in northern Ethiopia?

The initial interest in the Sacred Forests in the Amhara Region was how these spaces have resisted deforestation. In the case of the church forests, there are a number of interesting issues that are raised, the first is the tension between aerial imagery which is incredibly powerful in terms of conveying the sense of these islands being an archipelago in a sea of land clearance. But also because the aerial imagery does not really give us a clear indication of the ecology of the forest, plant species, or layout of built elements such as churches. From the ground, an entirely different condition emerges, one that is saturated with different kinds of details and facts to do with materiality, imagery, and rituals such as leaving shoes outside before one enters spaces. The photogrammetry of the forest and church at ground level abstracts the architectural details of ritual around the forest and in the church. But the incompleteness explores these unique places as a system of resistance. And leaves space to imagine how nature can be reintroduced into the landscape.

Population growth, disease outbreaks, climate change, and impending natural disasters pose challenges for the future of public space, particularly in dense urban areas. What do your future reimaginings of public space look like?

Half the world is on the Internet. Potentially the comment section and chat box will become our public space.

Interview by Jareh Das.

Images courtesy Ibiye Camp.