FORMULA ONE AND ARCHITECTURE: On Ingenuity, Engineering, And Processing Environmental Data

Like many of us, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, I developed a quarantine hobby. I am quite unsure as to how I arrived at that side of cable, but one lazy Sunday afternoon, I began watching Formula One. On the TV screen was an inundation of graphically represented statistical information. The bottom right corner showed the track layout, with multicolored dots constituting the relative positions of cars on the track. On the left side of the screen, the drivers were arranged from 1st to 20th position, with their intervals ever-changing by tenths of seconds.

The 2017 Abu Dhabi Grand Prix broadcast on television at a home in New Forest, Britain. Photography by Stan Papior.

To put it lightly: I was confused, but I was also completely enamored by a sport that required so much data processing. Graphics revealed the driver's tyre pressure, a percentage I soon learnt was dependent on weather conditions and the heat of the track. Every so often the commentator’s voices would be muted, in their place, a radio check-in revealing the mid-race strategy negotiations between a driver and their primary engineer. All this information felt like a personal gift, this was a sport enriched by the distinctive circumstances of its given environment, and I was being given all the information necessary to understand it. I felt taken care of; and football has never made me feel like that.

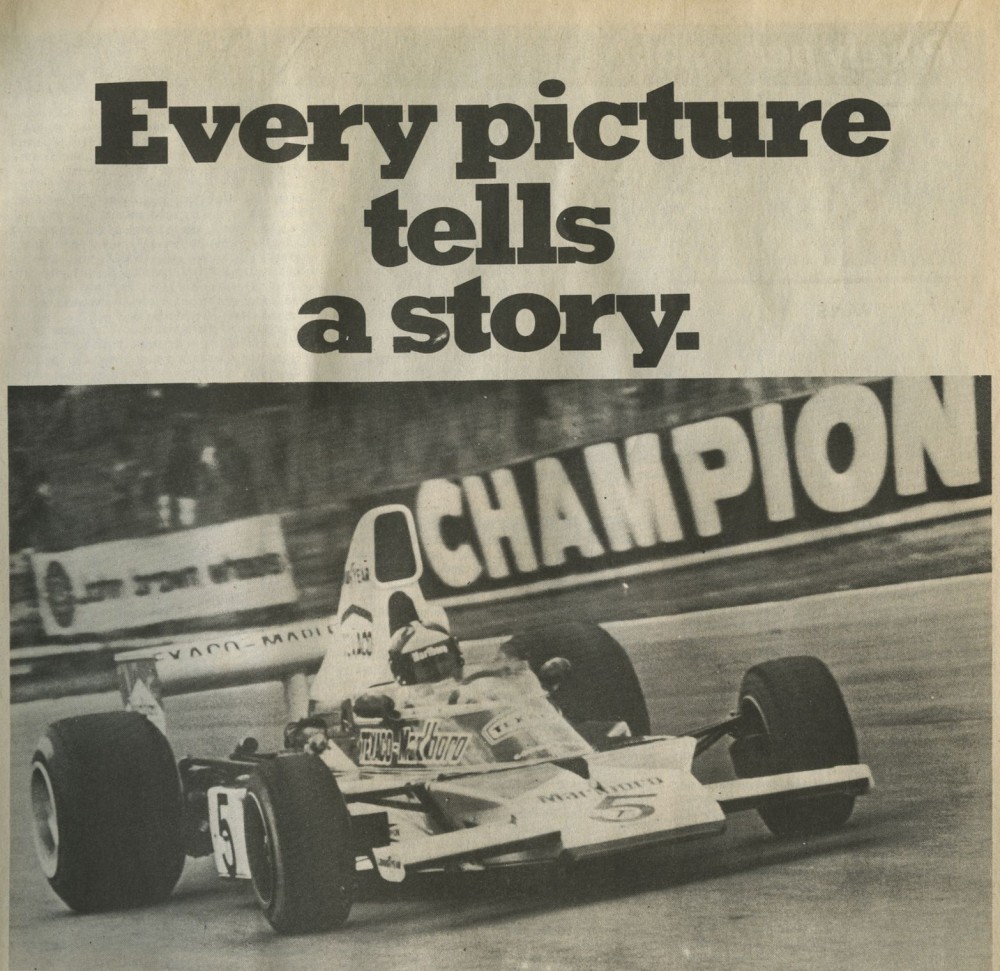

Vern Schuppan wins final Rothmans F5000 race. Image from the October 24, 1974 cover of Autosport.

In an attempt to cater to American cultural literacy, F1 could be thought of as NASCAR’s posher, wealthier, and more fashionable sibling. The European-born championship is the top-tier of motor racing, where ten teams and 20 drivers compete to come out on top — earning millions of dollars in the process. Mercedes Benz, Ferrari, and Red Bull; one of these is not like the others, but all of these brands form the holy trinity of teams at the top of the auto racing championship giant that is Formula One (F1). The sport is filthy rich, of course Red Bull wants apiece.

Fernando Alonso of Spain driving the number 14 McLaren F1 Team MCL33 Renault crashes with Charles Leclerc of Monaco driving the number 16 Alfa Romeo Sauber F1 Team C37 Ferrari at the start during the Formula One Grand Prix of Belgium at Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps on August 26, 2018. Photography by Mark Thompson/Getty Images.

Each team in Formula One produces two identical cars, one for each of their two drivers. The teams compete on a point-based system where the higher up a driver places at the end of the race, the more points they score for themselves, and their team. Simply enough, the driver with the most points wins the driver’s championship, and the team with the most points — based on the performance of both of their driver’s vehicles — wins the constructor’s championship. We might consider each circuit as a site, and the driver akin to the ‘starchitect’: the face of the well-oiled machine.

View of the track at Circuit of the Americas 2015 in Austin, Texas. Photo courtesy of Circuit of the Americas.

The secret of Formula One is that what happens on the track is only half the story. The cars are built from scratch in labs during the off-season, and the driver and on-site team are tasked with bringing that engineering to life. F1, like architecture, is an intensely collaborative practice. In architecture this practice can become tied to one figure and likewise in F1, the success of a team is all too often pinned on the driver alone.

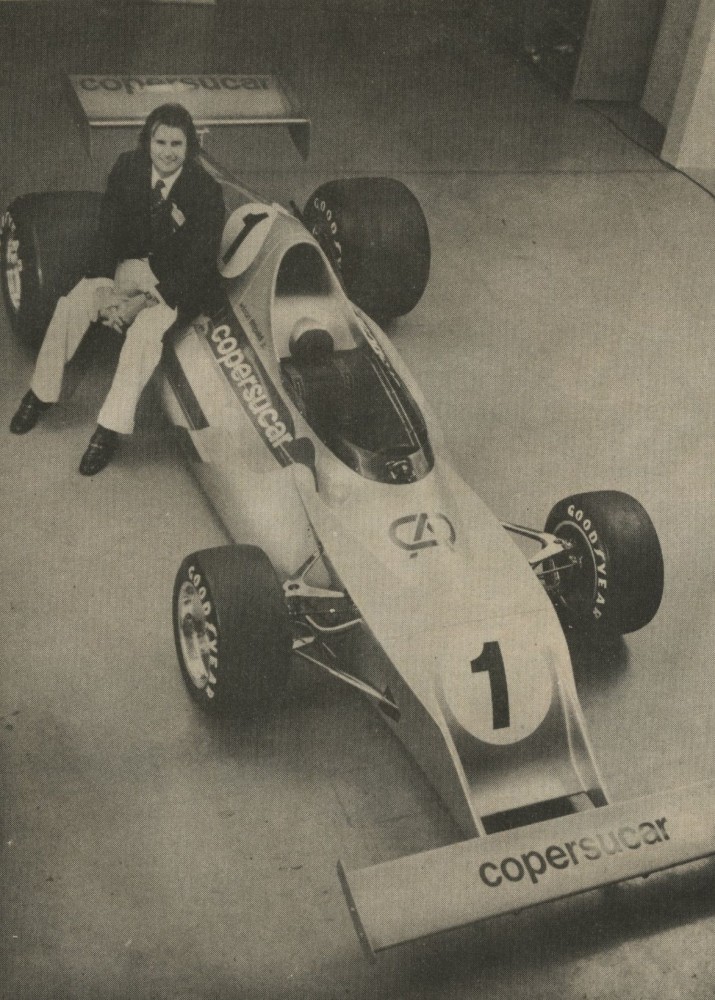

Emerson Fittipaldi, winner of the 1974 Formula One World Championship. Image from the October 24, 1974 issue of Autosport.

The Formula One World Championship was established in 1950, the same year Zaha Hadid was born. Hadid would later be known as one of the most important starchitects of our time, and the same questions of celebrity and authorship that surround the term starchitect would soon be applied to discussions of the role of a Formula One driver. The spirit of F1 is carried by its drivers, and the sheer diversity of the sport’s fans is mirrored by the assortment of drivers in the paddock. There is the charming, ever-grinning Australian “honey badger”, Daniel Ricciardo, the lovable Kimi Raikonnen with his incessant RBF, and the ‘Serena Williams’ of F1, seven-time Formula One champion, Lewis Hamilton. In the world of F1, there is an ever-present question: “Is it the driver or the car?” Who authors the win?

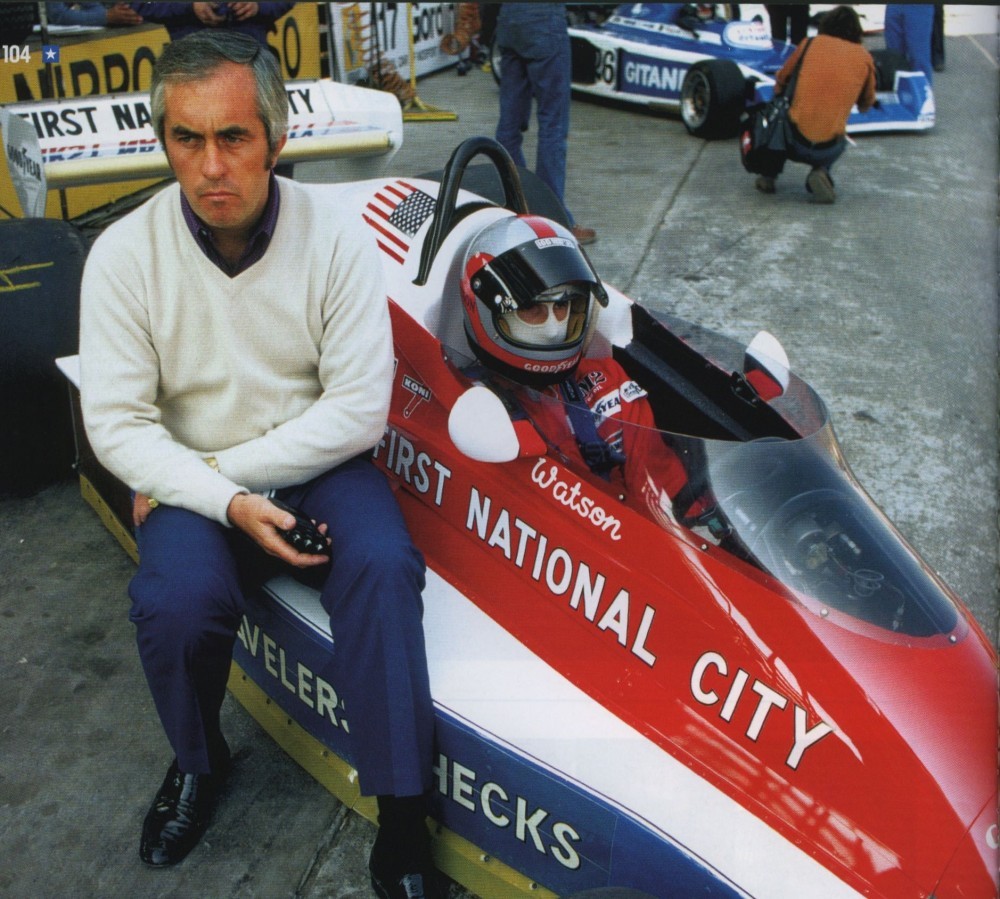

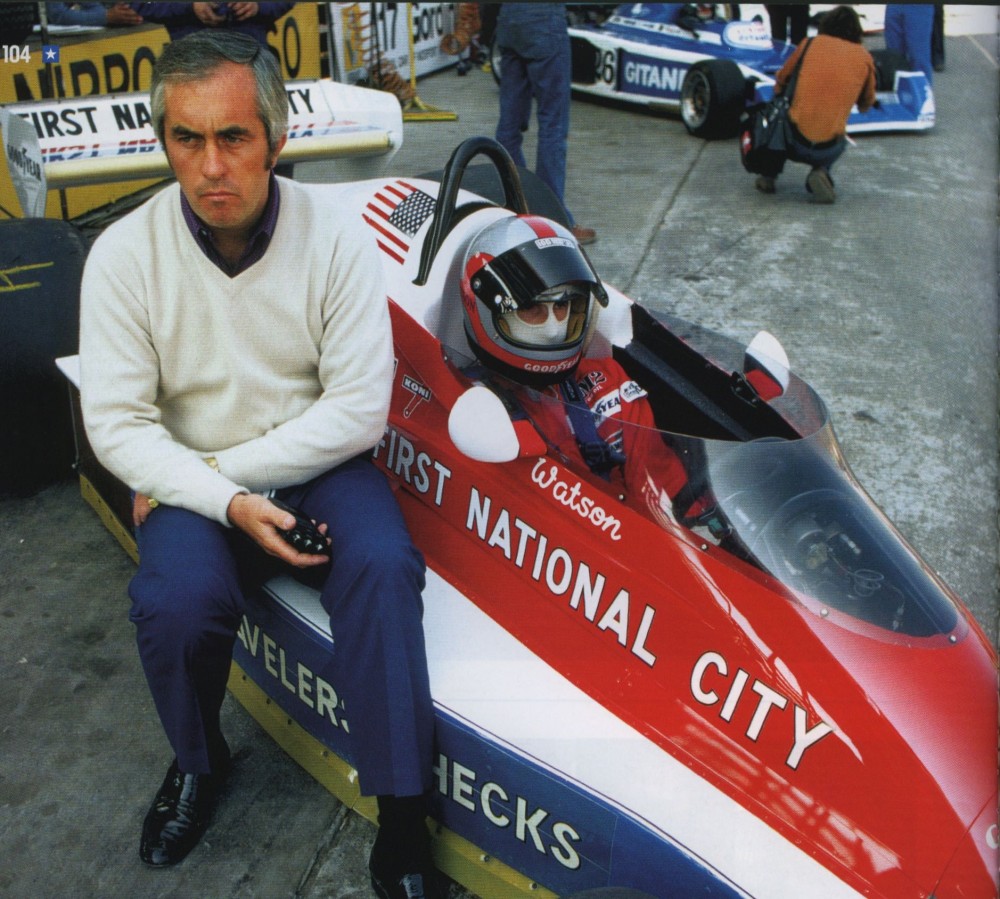

One of the biggest names in IndyCar and NASCAR, Team Penske took on the world and won when it entered Formula One in the 1970s. Image from a 2015 issue of F1 Racing.

In the cult of personality that forms around starchitects, it is too easy to forget the underpaid, and overworked interns who contribute to the success of their firms. While the importance of teamwork is better nurtured in the culture of F1, the team dynamics in the sport are analogous to questions that have long plagued the discipline of architecture. In contemporary understandings of architecture, one might be inclined to deny Leon Battista Alberti’s proposition that architects must know how to realize the construction of their buildings. While an architect must understand these structural dynamics enough to design a “buildable” building, detailed knowledge of construction techniques is not often thought of as being part of an architect’s job. Similarly, a Formula One driver must understand race conditions and engineering limitations enough to favorably adapt their driving, but they are not expected to detail how an engine operates, or even how a car is optimized to prioritize their survival in a crash. Drivers, like architects, need to know enough to get the job done. But they must also acknowledge that the work is much bigger than their role in it.

Sebastian Vettel, Ferrari SF90 pit stop for front wing change after contact with Max Verstappen, Red Bull Racing RB15. Sunday, July 14, 2019. Photography by Mark Sutton/ Motorsport Images.

Despite the global pandemic, Formula One’s 2020 season reached 13 countries across three continents in a line-up of 18 races. The sport’s reliance on the urban conditions it temporarily occupies makes the culture around F1 uniquely riveting. Like most sports, its participants attempt to occupy space in the most advantageous way, relative to their opponents. F1 takes these spatial dynamics one step further, as a sport that prioritizes the situational richness of each track.

1970s Shell ad in the October 24, 1974 issue of Autosport.

Each track is completely different. Unlike NASCAR, where drivers loop around an oval endlessly, each F1 track has a unique combination of chicanes and straights that mean you never know how a race might unfold. Drivers are tasked with memorizing each of the 14-18 circuit layouts that might be on a calendar, to ensure they know exactly when to break and release, allowing for optimum speeds at each turn. In addition to the driver’s spatial and muscle memory, teams must then adapt their strategies to the unique weather, grip, and topographic conditions that each circuit has to offer.

Daniel Ricciardo, driving the number 3 Aston Martin Red Bull Racing RB14 TAG Heuer, makes a pit stop for new tires during the F1 Grand Prix of China in Shanghai. Image courtesy TotalPoster.

And still, the site-specificity of the sport extends to its fanfare. The pageantry of each F1 race shifts to accommodate the cultural conditions of each location. The Yas Marina Circuit, in Abu Dhabi, is the only track in the F1 calendar to boast a five-star hotel built directly on the track, designed by New York-based firm, Asymptote Architecture. For the Monaco Grand Prix, billionaires can watch the race from the comfort of their yachts, with hospitality packages selling out months in advance. You’d be right to think of F1 as an ostentatious display of wealth, but not all races match the prestige of these two aforementioned. The Austrian Grand Prix, for example, is incredibly picturesque and pastoral, miles away from the intensity of street circuits such as Monaco or Singapore.

Amoco advertising they are the superior motor oil for Formula One racing in the October 24, 1974 issue of Autosport.

An F1 car is a scientific accomplishment, a formidable feat of engineering, but this work cannot exist in isolation. The mechanical logistics must marry the driver’s skill during the race weekend, and these operations must in turn consider environmental conditions. These facets acting in concert allow for the exquisite motorized choreography of an F1 race. Both F1 and architecture are examples of masterful combinations of engineering, individual ingenuity, and spatial understanding. The architect is in the driver’s seat but must perform amidst site-specific quirks that define freedom of architectural expression. This expression engages a more visceral human experience, trusting that acts of engineering will bring these architectural metaphysics to life.

Text by Oluwatobiloba Ajayi.