ECCE HOMO: In Venice An Exhibition Hopes to save Europe through Craftsmen

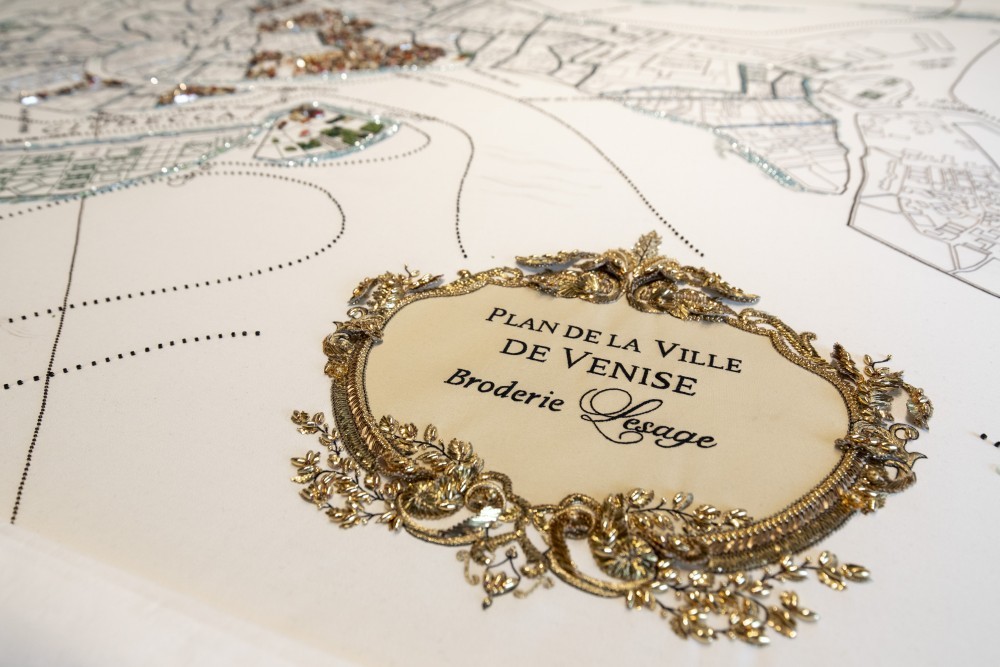

Have you heard of the Michelangelo Foundation? Neither had I. But the Geneva-based operation is certainly making a splash in Venice right now (pun intended) with the exhibition extravaganza Homo Faber, on show in the exquisite setting of the Fondazione Cini, on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. Homo Faber — “man the maker” — is all about handicraft, but not the macramé your aunt used to do or the pot making your sister tried at school. Rather it’s a celebration of the very best of highly trained artisans, those extraordinary talents who marry years of skill-honing with a deep understanding of their craft to produce objects of — as the curators are not in the least afraid to call it — beauty. Everything is celebrated here, from jewelers to book binders, from embroiderers to bicycle crafts(wo)men, from Ferrari restorers to old-master restorers in 16 very different spaces — among them a 17th-century library and a 1960s swimming pool — in this former Benedictine monastery.

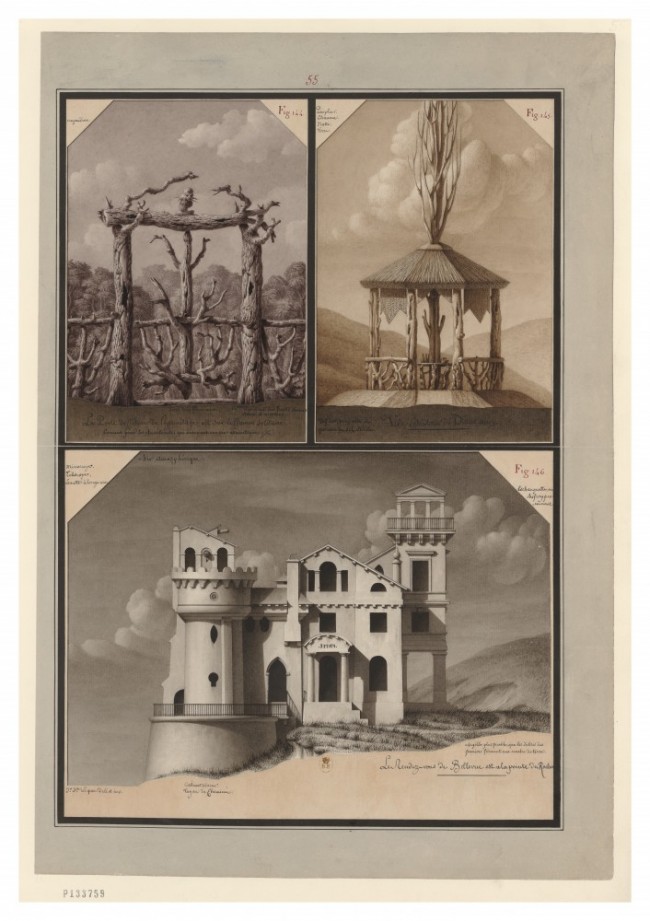

Exhibition view of Homo Faber “Imaginary Architecture” section at Fondazione Cini, Venice. Photo by Tomas Bertelsen

Johann Rupert and Franco Cologni are the two men behind the Michelangelo Foundation, which was founded three years ago in Geneva. South African native Rupert is the chairman of the Richemont luxury conglomerate, parent company to, among others, Cartier, Alfred Dunhill, Van Cleef & Arpels, and Chloé. Italian Cologni is a cultural critic, historian, and businessman as well as the former chairman of Cartier International, and now sits on the Richemont board. According to the two men the foundation, “promotes and perpetuates master craftsmanship” in a “fast-paced, mechanized, and hyper-technological world” where “the culture of the tangible, the durable, the physically valuable has given way to the intangible, the ephemeral, the disposable.” Aiming to resist this process, the Michelangelo Foundation has set out to encourage the “small but determined counter-revolution” which will see us “returning to that which ties us to our very humanness … rediscovering the value of objects of lasting beauty that only the hand can create.” To help them in this they’ve hired Alberto Cavalli as the foundation’s executive director; a former communications director at Dolce & Gabbana, Cavalli currently teaches in the design department of the Politecnico di Milano — his course is entitled simply “Bellezza italiana” (“Italian Beauty”) — and is the author of a book, Il valore del mestiere, that sets out to devise a reliable quality-control system for evaluating excellence in the Italian métiers d’art.

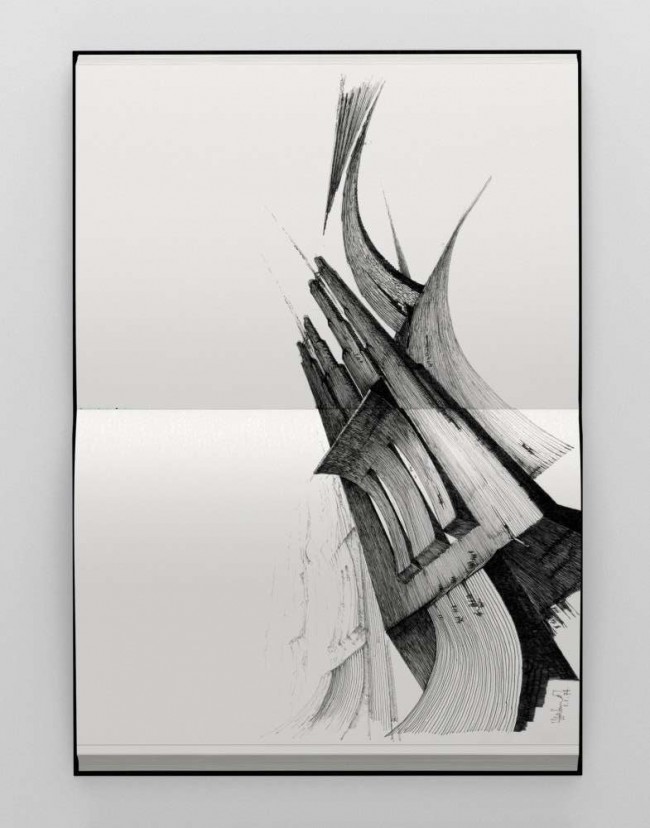

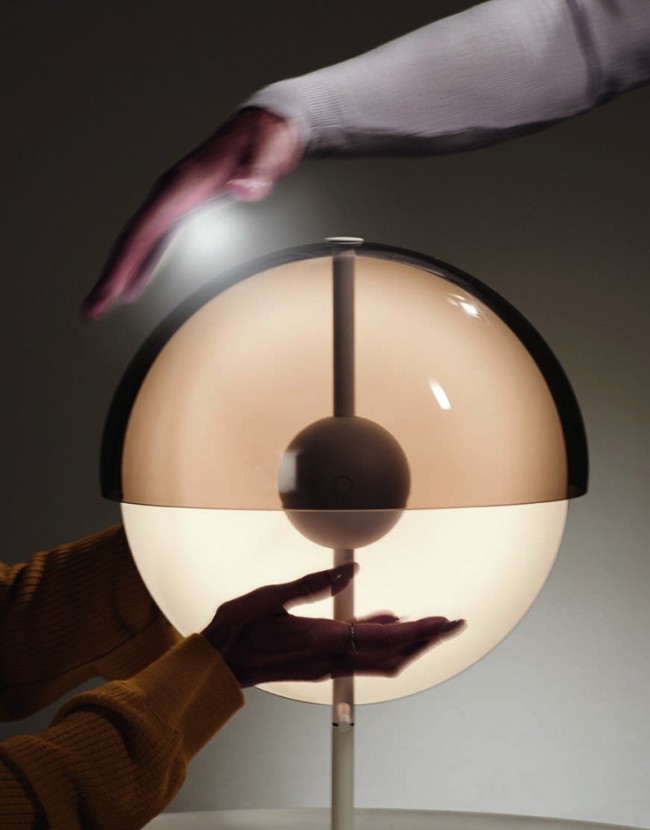

Exhibition view of Homo Faber “Creativity and Craftmanship” section at Fondazione Cini, Venice. Photo by Alessandra Chemollo.

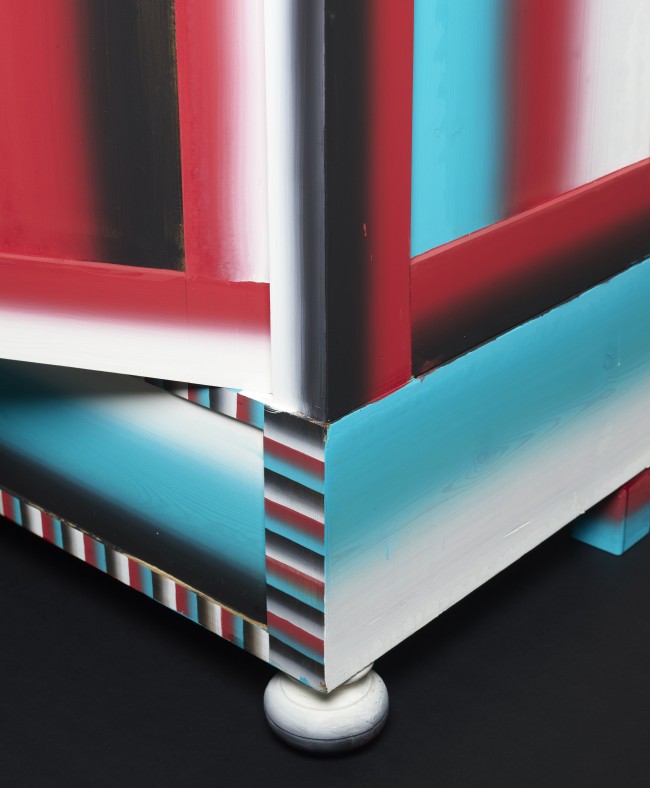

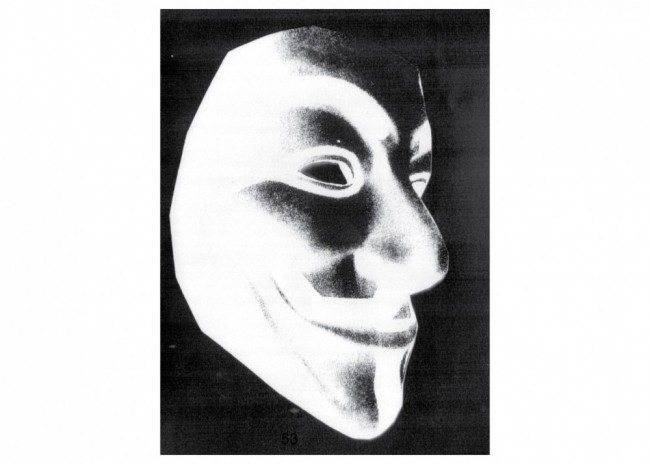

There’s a lot on offer at Homo Faber, from a Turkish bazar of objects assembled by Jean Blanchaert, to a collection of unique tabernacula commissioned under the aegis of Michele De Lucchi, to a runway show curated by the London College of Fashion’s Judith Clark (in the beautiful disused pool), to an exquisite selection of vases chosen by the Milan Triennale team (shown in Baldassarre Longhena’s Baroque library — but hats off to apml Architetti Pedron/La Tegola for their extremely intelligent scenography), to two entire interiors, one in rattan the other in color-saturated fabric, by India Mahdavi. But what really makes this show different from most other design exhibitions you’ve seen is the presence of almost two-dozen craftspeople on site making things — masters of their art who are more than happy to show you, and tell you all about in great detail, what they do. Once you’ve gotten over any unease you might feel about being at the zoo — these cooped-up mestiere are billed as an endangered species after all — you’ll have a fascinating time quizzing the enthusiastic young Hermès saddle-maker, the eagle-eyed Van Cleef & Arpels gemstone cutter, or the poised Nymphenburg porcelain painter about the history, techniques, and difficulties of their craft.

-

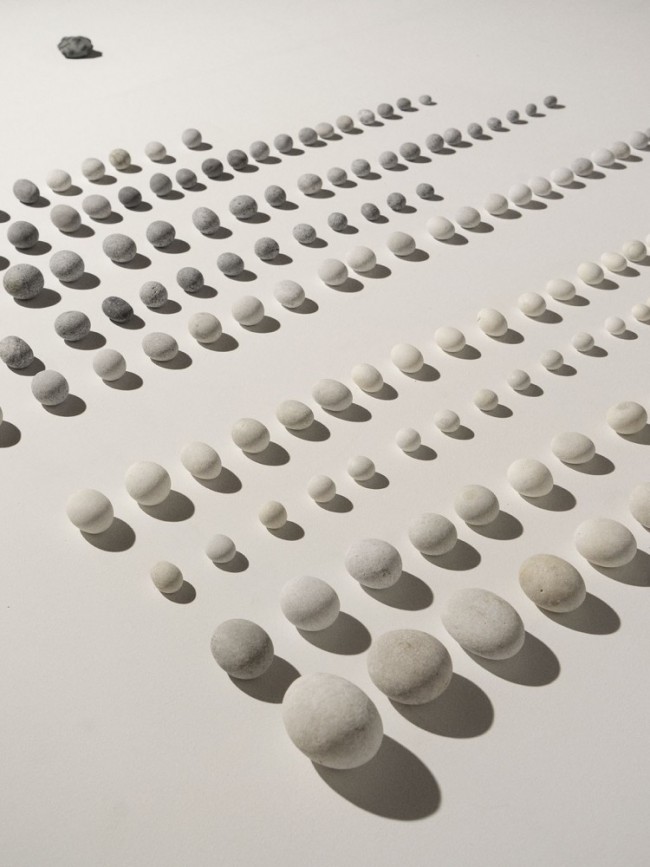

Exhibition view of Homo Faber “Restoring Arts Masters” section at Fondazione Cini, Venice. Photo by Alessandra Chemollo

-

Exhibition view of Homo Faber “Discovery and Rediscovery” section at Fondazione Cini, Venice. Photo by Tomas Bertelsen

-

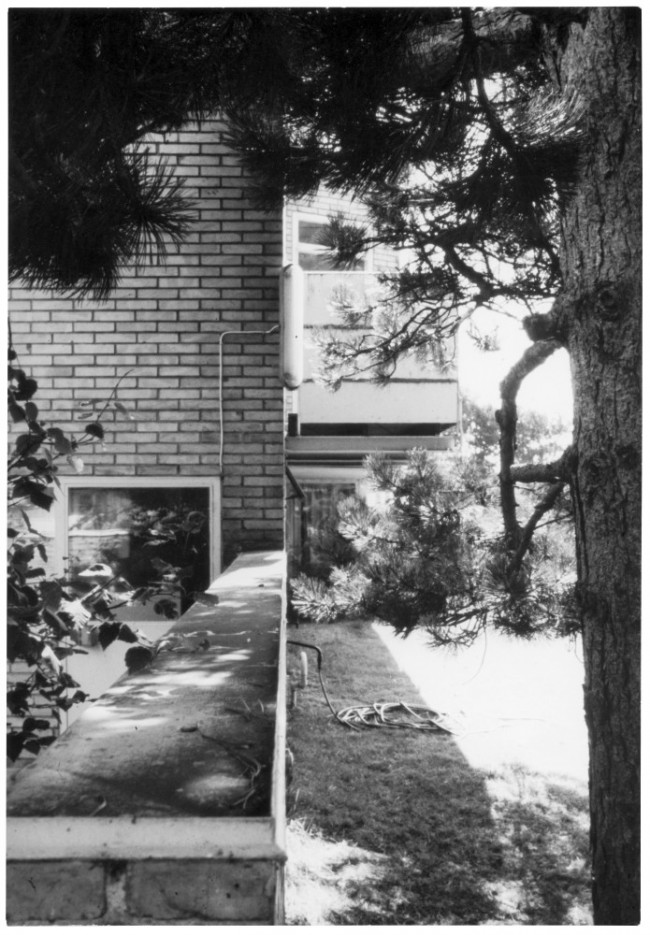

Exhibition view of Homo Faber “Restoring Arts Masters” section at Fondazione Cini, Venice. Photo by Tomas Bertelsen

Homo Faber’s official opening ceremony took place in mid-September in San Giorgio’s serene and sunny cloister, with all the usual introductory speeches given at this kind of event. Among them was a rousing address by Rupert, who fustigated the global response to the 2008 crash — “I warned our colleagues that should governments and central banks globally depress interest rates, repress savers, the good people in society would have their savings wiped out … (and) sooner or later find out they were taken advantage of by speculators that never went to jail” —, told of his dire predictions about what would follow — “I foresaw that we would see more anti-Semitism, that there would be a fracturing of the social fabric ... And what have we got today? We’ve got Brexit, we’ve got President Trump” —, and went on to lament the problem posed by artificial intelligence and robotics: “more people will lose their jobs and there will be more social conflict. So where,” he continued, “can we still compete with machines and where can Europe compete best? Culture, taste, fine craftsmanship. This means we really need to connect the master artisans — these true heroes — with potential buyers globally. This will be possible because in a few years’ time we will have a very efficient global electronic marketplace.” A case, it would seem, of joining ’em if you can’t beat ’em: the global super rich, as Mr. Piketty has warned us, will only get richer, so let’s all learn a master craft and get those zillionaires to spend some of their ill-gotten gains on our handiwork as they gad about decorating their palaces, wives, garages, and stud farms.

Exhibition view of Homo Faber “Fashion Inside and Out” section at Fondazione Cini, Venice. Photo by Alessandra Chemollo

Will this cunning plan work? In a country like Italy, where there are more small-scale artisans than you can shake a hand-carved stick at, perhaps. And it would certainly constitute a fitting revenge in a society where, in the past, everyone aspired to be a doctor, lawyer, or magistrate, and crafts were the lowest of the hired low. Artisans as the new elite! “I want to give back,” Rupert explained in a Vogue interview with Suzy Menkes (and, in that vein, not only does Homo Faber not charge admission, there’s also a free boat shuttle from Piazza San Marco). “Extinction should never happen,” Rupert continued. “We should collect (crafts) people from all over the world so that they can survive and thrive.” In his opening speech he announced that Homo Faber is all set to be a biennial — so if you can’t make it this time around, come back in 2020 to see how he and the Michelangelo Foundation are getting on.

Text by Andrew Ayers.

The exhibition Homo Faber is on view at Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, until September 30, 2018.