BOOK REVIEW: Mohamed Elshahed’s Guide To Modern Architecture In Cairo

If someone says “Modernist city,” you immediately think Brasília or Chandigarh. If someone says “Cairo,” chances are you’ll think Egyptian antiquities or, at a pinch, the medieval walled town known today as “Islamic Cairo.” But, as historian Mohamed Elshahed points out in the introduction to his book Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide, the Egyptian capital “is essentially a 20th-century city. Its expansion and development during the past century surpassed the pace and scope of its growth over the previous millennium.” As a child, Elshahed says, he was exposed to an immersively Modernist environment whose specificity only struck him later, when he studied in the U.S. But in American discussions of Middle Eastern architecture, he discovered, this landscape of Modernism was completely absent. “As much as I have a lot of deep appreciation for the ancient world and for Islamic heritage in architecture. The world I came into, and who I am, are shaped by the 20th century. And this is really why I felt it was my mission to record and theorize this era in terms of its architectural production.”

Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide, by Mohamed Elshahed (The American University in Cairo Press, 2020).

One of the results of that recording process is Cairo Since 1900, a guide to the city’s 20th- and 21st-century architecture that catalogues 226 sites in the central areas of the city. Perhaps something of a personal quest for identity, the book was also written as a call to arms to save an architectural heritage that is under threat. As Elshahed explains, while heritage protection does exist in Egyptian law, it’s not always enforced, and comes with some perverse side effects. Any building over 100 years old is eligible for heritage listing but, in a country where Modernism is not appreciated, and where having your 1920 apartment block designated a historic monument brings no financial rewards (leading instead to potentially expensive restoration costs), the 100-year deadline is an incentive to demolish. “It’s a death sentence that’s been handed down to Modernism in Egypt,” declares Elshahed. “The result is an onslaught that’s getting worse as the years go by towards buildings that in other countries would be considered part of a cherished heritage.”

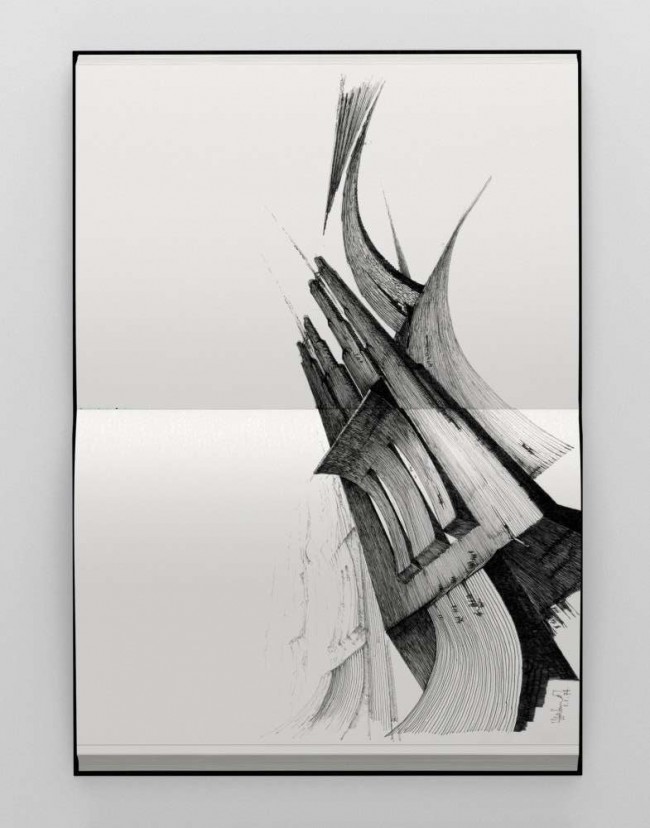

Maadi Palace Building (1996) by Ashraf Salah Abu Seif.

Which begs the question, “Why are these buildings not cherished?” That, Elshahed says, is due to the political spin put on Modernism as a Western import, the legacy of a failed attempt at secular modernity, and therefore not authentically of its place. “Modernism within Egypt has not been fully accepted because of that narrative,” continues Elshahed. “In the 1970s and 80s there was this search for identity, and that’s when a figure like Hassan Fathy became prominent in international circles as an architect who wasn’t simply ‘copying’ the West.” But for Elshahed, this politicized nationalist narrative is too simplistic. “If Egyptian Modernism is illegitimate because it was purely the outcome of contamination with Western ideas, then one can also argue that Western modernity was itself only possible because the West ‘contaminated’ itself with the rest of the world — through colonization, extraction of resources and ideas, the documentation and recording of art from everywhere to India to Cambodia to Egypt, etc. Our planet has long been a highly interconnected place.”

-

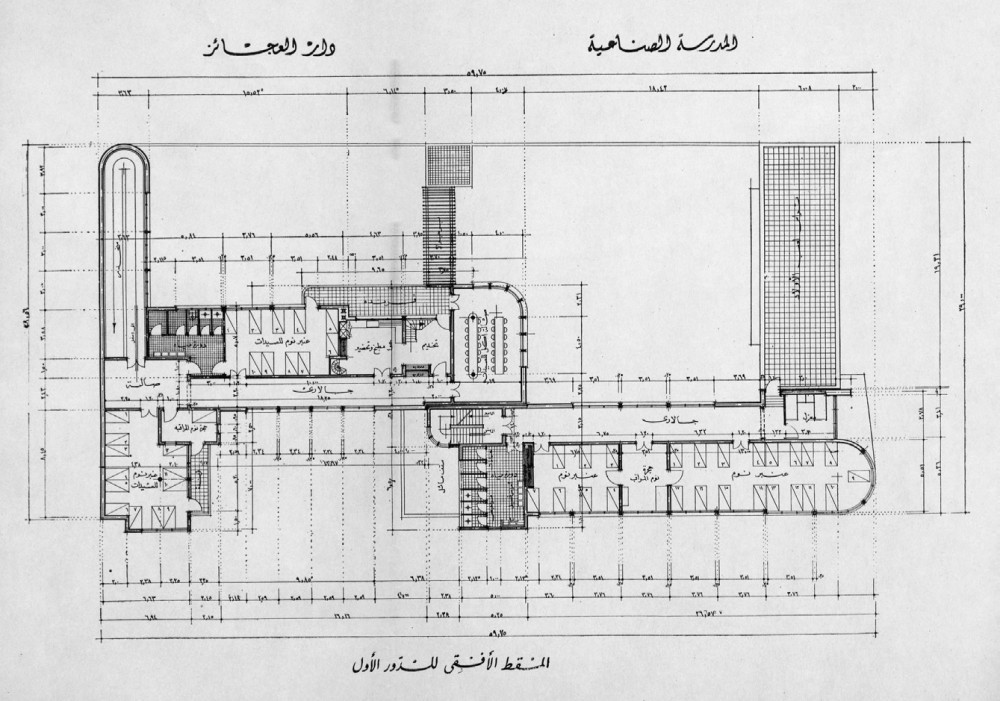

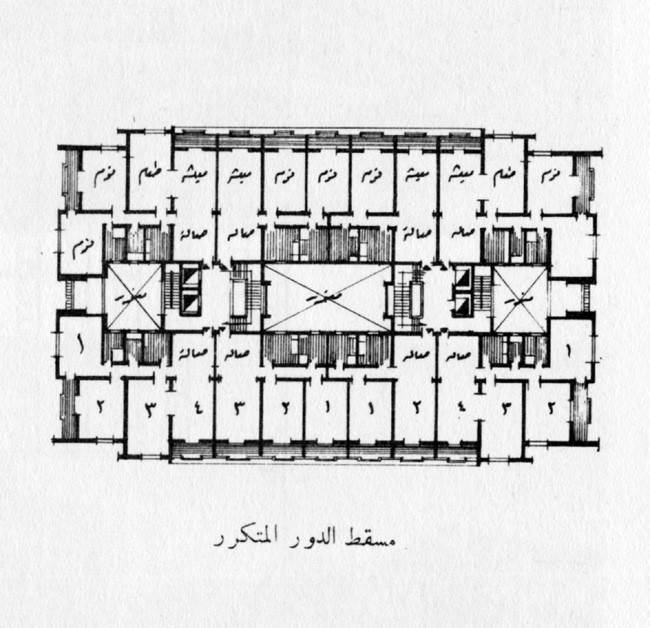

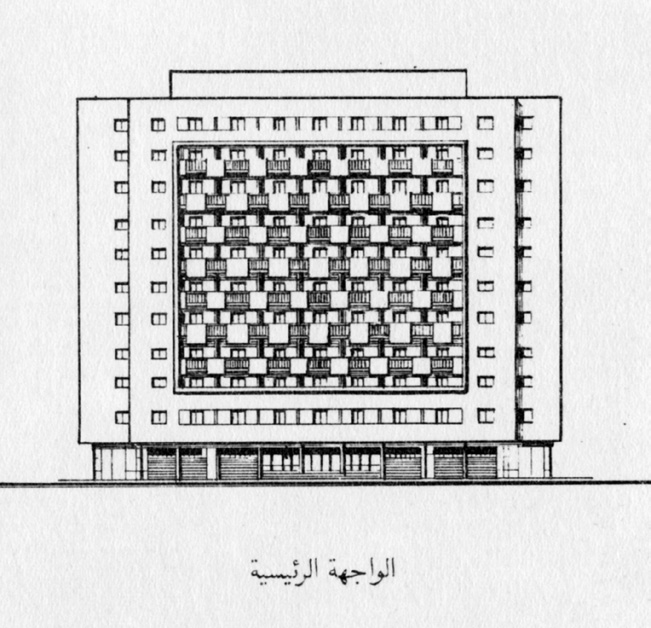

Elevation drawing of Housing Model 20 (1959) by Ali Labib Gabr, Ahmed Charmi.

-

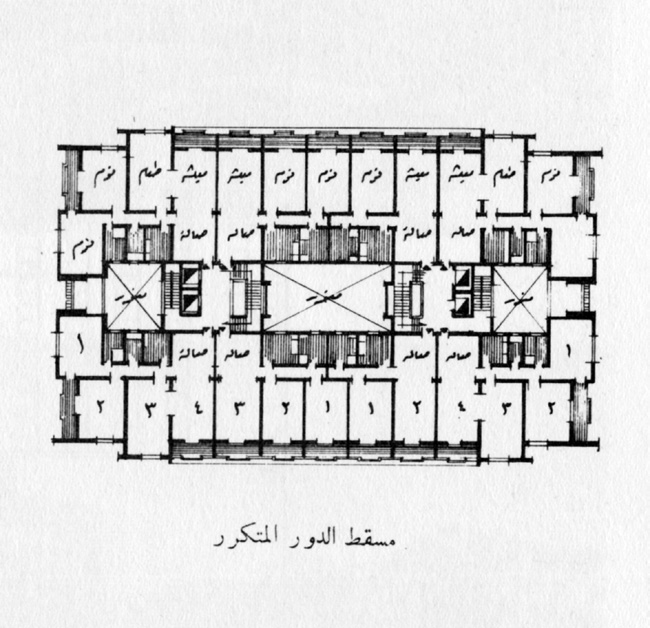

Plan of Housing Model 20 (1959) by Ali Labib Gabr, Ahmed Charmi.

As an inventory of 20th-century Cairo (alas incomplete, Elshahed says, due to the paucity of interest and of archival material), the book covers everything from apartment buildings, law courts, mosques, and museums to print-works, private villas, workers’ housing, banking and insurance offices, churches, schools, and synagogues. It also includes demolished buildings as a wake-up call to what has already been lost. Elshahed’s favorite of all — still standing — is the villa that Cairene architect Sayed Karim (founder, in 1939, of Egypt’s first Arabic architecture review, Al Emara) built for himself in 1947–48, designing everything including the furniture. And of course the book takes us to Heliopolis, the former desert suburb created ex nihilo from 1905 onwards by Boghos Nubar, son of the then prime minister Nubar Pasha, and Belgian industrialist Édouard Empain. Empain’s 1911 concrete “Hindu” palace, by Alexandre Marcel, gives a hint of the eclecticism to be found in 20th-century Cairo’s modern architecture.

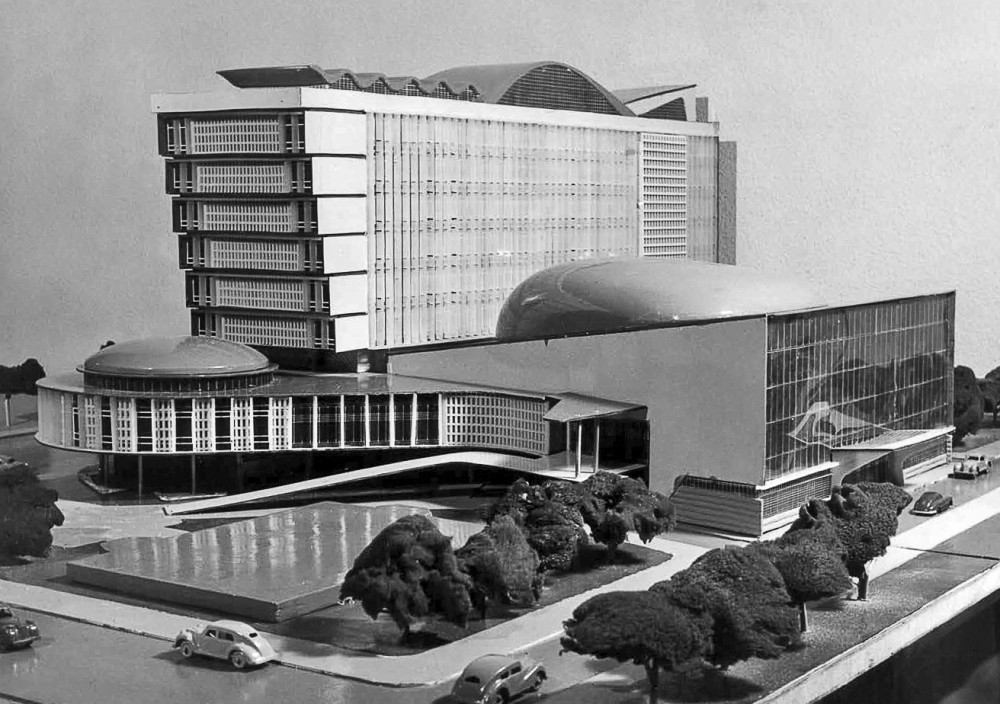

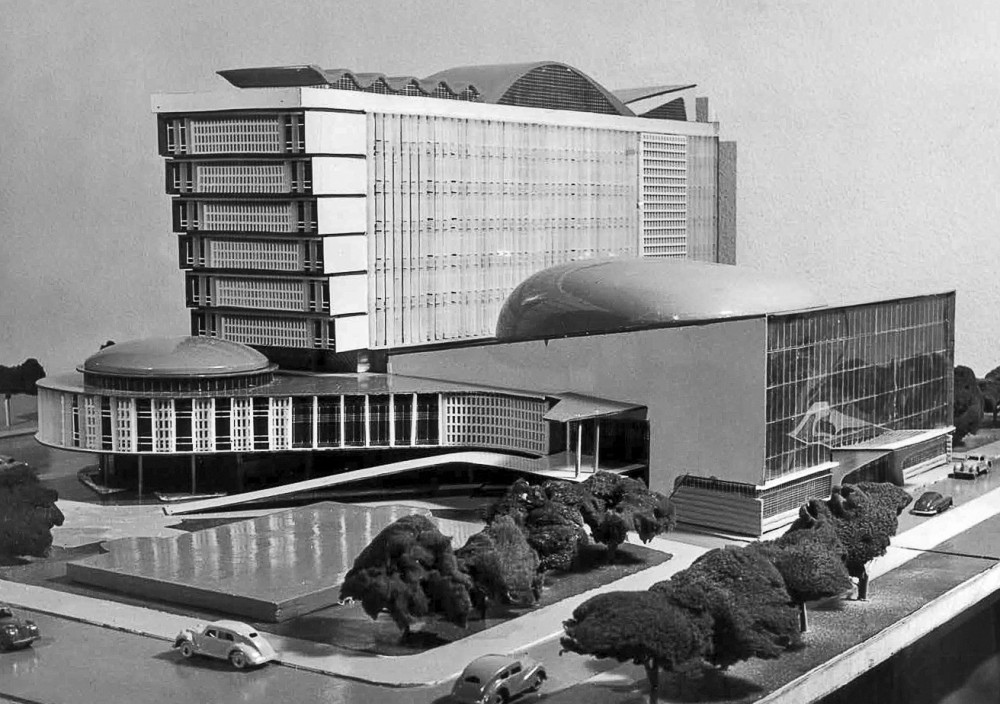

Islamic Congress Secretariat (1957) by Sayed Karim.

If Elshahed chose the guide format, he says, it was to make the subject accessible to as many as possible in order to raise awareness of Cairo’s Modernist legacy, particularly among Cairenes. With the first print run already sold within a few months, it’s a tactic that seems to be bearing fruit.

Once the coronavirus pandemic finally abates, New Yorkers will be able to get a more immediate taste of Elshahed’s work at the Center for Architecture, where he has curated Cairo Modern, an exhibition that, by highlighting 20 buildings from the book, draws out some of the themes raised by the legacy of 20th-century architecture in Egypt’s capital.

Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide, by Mohamed Elshahed (The American University in Cairo Press, 2020).

Text by Andrew Ayers.

Images courtesy The American University in Cairo Press.

Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.