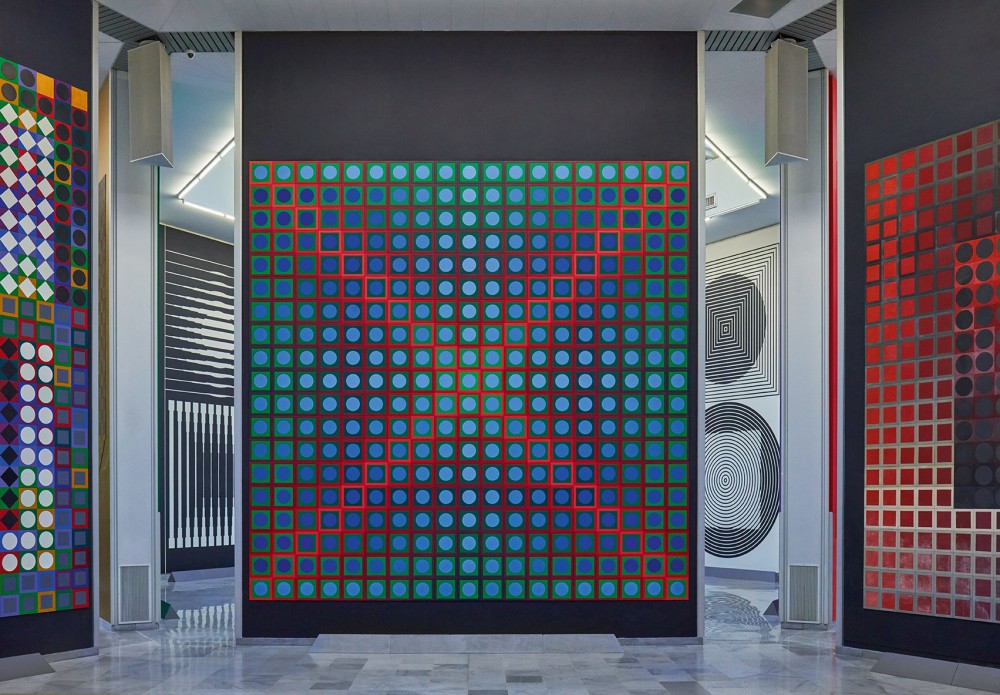

RESIDENT ALIENS: Victor Vasarely Seen Through New Eyes

Fondation Vasarely photographed by Philippe Jarrigeon for PIN–UP 27.

Though hardly a household name, millions of international tourists have seen Victor Vasarely’s work. That 4 x 5-meter slatted-aluminum portrait of President Pompidou hanging in the entrance to his eponymous Parisian center? It’s by the Hungarian-born French artist (1906–97), who was honored with a major retrospective at the Centre Pompidou last year (his first in 50 years).

Fondation Vasarely photographed by Philippe Jarrigeon for PIN–UP 27.

As the show made clear, Vasarely is a one-man encapsulation of the art movements of the early to middle years of the 20th century. Too young for Cubism, he started out in a Bauhaus vein at art school in Budapest, absorbed Giorgio de Chirico and Surrealism and put them to good use in his advertising career in 1930s Paris; he then went through a Jean Arp-style biomorphic phase in the 40s, before his breakthrough into black-and-white geometric abstraction in the 50s (e.g. Hommage à Malévitch, 1954–58). Then, at the dawn of the 1960s, colors burst forth in Vasarely’s work, with a resounding Pop!, and the psychedelic Op Art for which he is best known came triumphantly into existence.

Fondation Vasarely photographed by Philippe Jarrigeon for PIN–UP 27.

Soon his art was everywhere: on TV studio sets and book and album covers (Bowie’s Space Oddity), in films and open-air sculptures, on cars and garages via his Renault-logo redesign, and also on buildings, both inside and out. It was only a matter of time before Vasarely turned his hand to architecture itself.

Fondation Vasarely photographed by Philippe Jarrigeon for PIN–UP 27.

He had described his ideal of a “polychrome city of happiness” as early as 1956, a place where art would not only be ubiquitous but, through its language — scientifically derived and based on visual coding, permutations, and algorithms — would form part of a “planetary folklore” capable of uniting the whole of mankind in the atomic age (his was a life indelibly shaped by two global conflicts).

Fondation Vasarely photographed by Philippe Jarrigeon for PIN–UP 27.

In 1966 he began work on an eponymous foundation that would put his ideas into practice, a building he designed himself with help from architect Claude Pradel-Lebar (construction being realized by Jean Sonnier and Dominique Ronsseray). Inaugurated in 1976, the Fondation Vasarely sits on a grassy slope outside Aix-en-Provence, a site of symbolic import since it’s close to a property once owned by the Cézanne family, and enjoys sweeping views over the Montagne Sainte-Victoire, which Paul Cézanne so often painted.

Fondation Vasarely photographed by Philippe Jarrigeon for PIN–UP 27.

Like one of Vasarely’s artworks extruded into three dimensions, the building is generated from a cellular, hexagonal plan, each chamber of this utopian honeycomb being top lit and filled with “Intégrations,” as he baptized the large-scale architecture-integrated artworks it contains. In the manner of a billboard, the Fondation’s exterior, with its boldly geometrical black-and-white aluminum panels, announces what’s to come, but does nothing to prepare the visitor for the shock of color inside. Nor for the variety of materials, canvas, ceramic, metal, and even fabric being used to monumental effect in an immersive total environment of optical overload.

Fondation Vasarely photographed by Philippe Jarrigeon for PIN–UP 27.

While Vasarely has become enduringly identified with the pre-oil-crisis optimism that reigned in the technocratic France of the Citroën DS, Concorde, and Ariane, his work aimed for a universality and timelessness whose means of expression might, perhaps, chime once more in the otherworldly flatness of our post-Postmodern, digital age.

Fondation Vasarely photographed by Philippe Jarrigeon for PIN–UP 27.

Photography by Philippe Jarrigeon.

Text by Andrew Ayers.

Animation by Jason Harvey.

Lighting and retouching by Anna Muslimova.

Taken from PIN–UP 27, Fall Winter 2019/20.