Design Genre-Busting In Brussels: One Fair and Three Shows

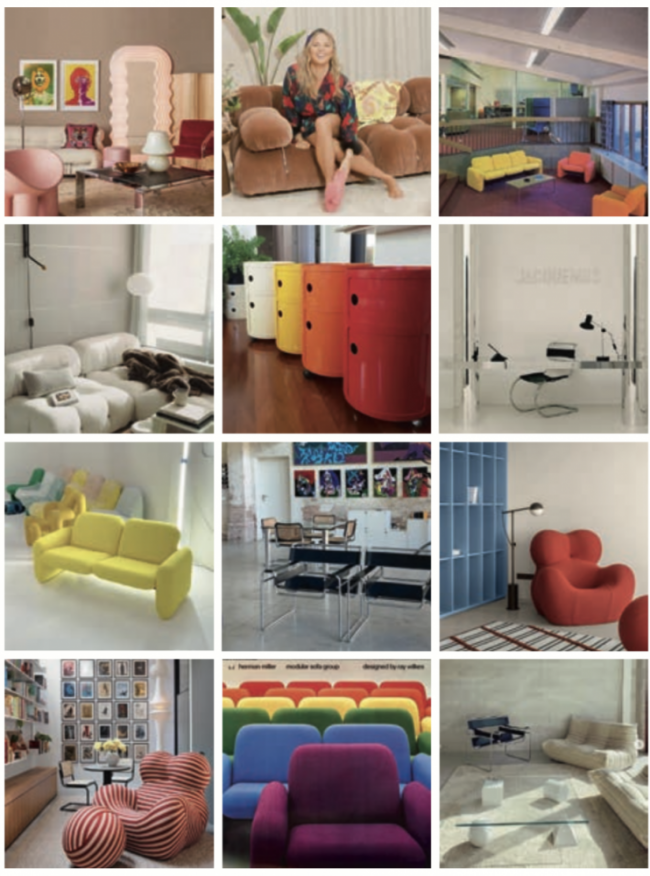

In early March, just days before COVID-19 shut down three-quarters of the globe, Brussels hosted the third edition of design fair COLLECTIBLE, billed as the only one on the planet dedicated exclusively to 21st-century unique or limited-edition pieces. The 104 exhibitors filled six stories of the city’s Vanderborght Building, a splendid piece of 1930s rationalism by architects Govaerts and Van Vaerenbergh that started out life, appropriately enough, as a home-furnishings-and-supplies store. Things have moved on a little in sophistication though, as was made clear by the presence on the ground floor of Berlin gallery Functional Art, whose name set the tone for much of what was on display at the fair: pieces that were aesthetically, functionally, or conceptually challenging, and sometimes all three. A case in point could be found immediately as you walked in, where U.S. gallery Todd Merrill Studio was showing several realizations by Brussels designer and architect Lionel Jadow, among them a transparent-glass wardrobe of which Philip Johnson could but only have been proud (perhaps Jadow will one day build a brick wardrobe to match).

-

Acrylic-resin pieces by Anna Aagaard Jensen with paintings by Richard Kennedy. Photography by Nicolas Schopfer. Courtesy Functional Art Gallery.

-

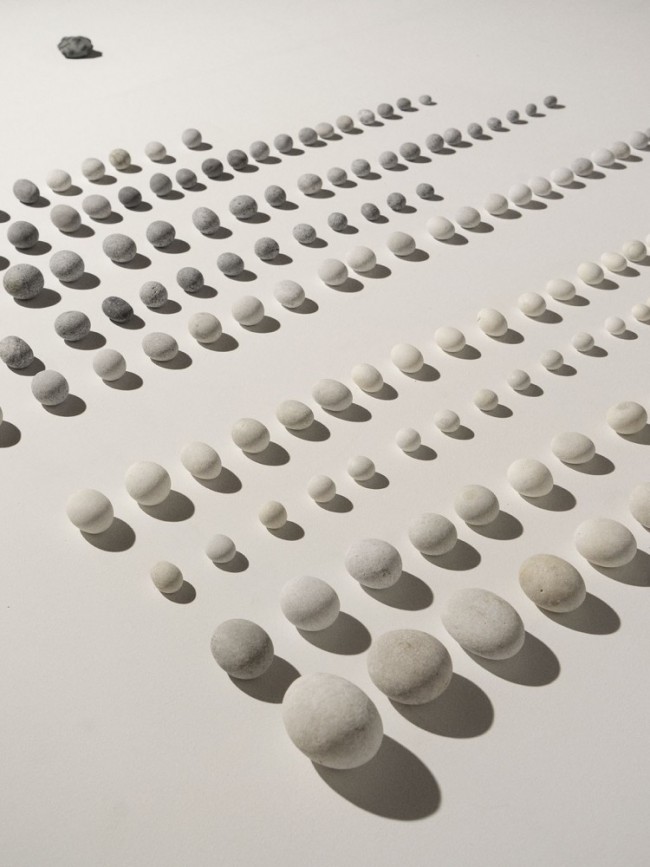

In the foreground: Rodrigo Pinto’s Tierras

Hipnóticas: Concrete consisting of marble grains, stone

carbonates, copper slags, and white cement; Ceramic with embedded bronze enamel. Presented by Side Gallery. Courtesy Collectible.

Elsewhere, an abundance of blobs dominated the stands. For example, of Barcelona-based Side Gallery showed Tierras Hipnopómpicas, a set of tables and stools by Chilean designer Rodrigo Pinto who mixed concrete, metal, and ceramic to dystopian Bilbo Baggins effect. The aforementioned Functional Art was showing a queer non-binary ballroom of pink acrylic-resin pieces by Danish designer Anna Aagaard Jensen set to a background of operatic paintings by Richard Kennedy. Every genre of material production seemed to be present, from precious hand-made pottery — Hanna Järlehed Hyving’s exquisitely beautiful and useless bowls, on the Valcke Art Gallery stand — to computer-milled, hand-finished marble — Ben Storms’s wonderful giant stone pillows — to literal trash, in the form of a lamp by Greek designer Savvas Lav made out of bits of Styrofoam packaging salvaged in the backstreets of Athens (shown in the “curated” section chosen by Brent Dzekorius to showcase young designers and studios not yet represented by galleries). And then there were the Zaventem Ateliers, a collective of Belgian designers, who mixed every medium going in The Extreme Ping Pong Experience, a ping-pong table conceived in the manner of that old Surrealist parlor game, the cadavre exquis.

-

On left: Parasite 2.0's Primitive Future sofa. Courtesy Collectible.

-

Brent Dzekorius curated a section of the fair showcasing works by young designers and studios not yet represented by galleries. Courtesy Collectible.

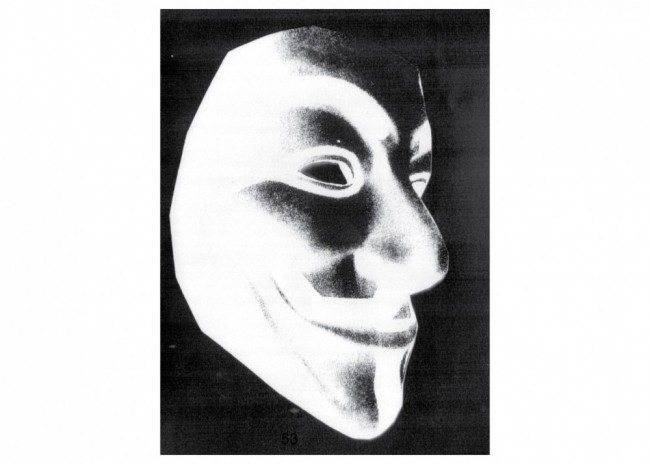

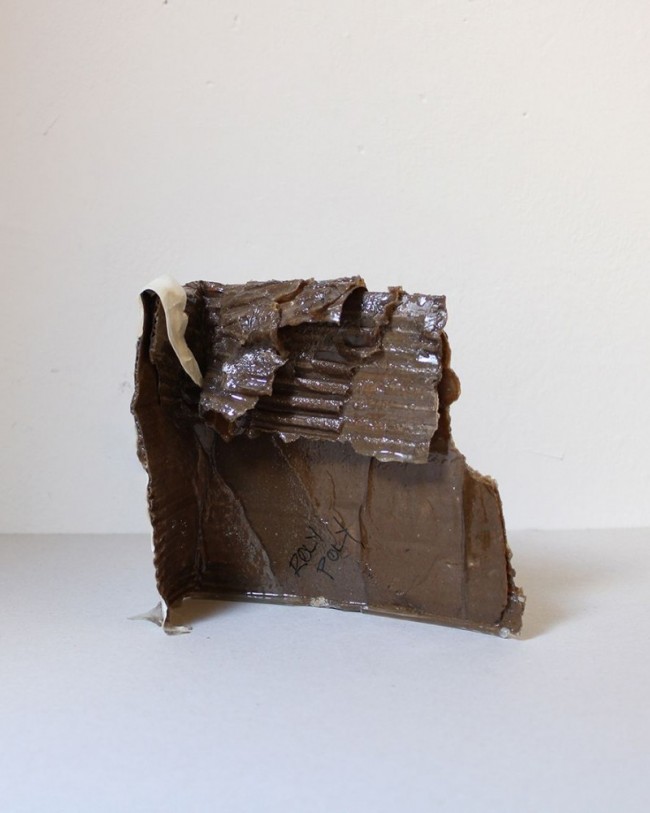

For Milan’s Camp Design Gallery, Italo-Belgian design practice Parasite 2.0 took rather the opposite tack, opting for mono-materiality when wrapping a sofa in blue sticky tape with the words “Primitive Future” printed on it. The piece, they explain, is “part of a series of object customizations starting from some limited-edition tapes, reflecting on aesthetical obsolescence, DIY actions, authorship, self-branding, and the production of waste from the furniture industry,” but presumably they hadn’t foreseen the irony of such of a plastic-wrapped, wipe-down future in the time of coronavirus. Some of the most eccentric pieces were to be found on the stand of Amsterdam gallery Rademakers, among them Dutch designer Pien Post’s table with matching chairs that cannot stand alone, but rely on the table for support, imprisoning their users within them; a wonderful trio of obsessive-compulsive pieces by the Rotterdam-based Diederik Schneemann — Matchbox King Clock, a grandfather clock made out of over 1,000 old matchboxes, Room divider soft focus, a folding screen covered with hundreds of 1970s 3D postcards, and the sublime 2nd Smurf Vase, a completely useless vessel made from hundreds of plastic Smurf figures; and last but not least Ted Noten’s Ratasmile (2007), a rather extreme critique on the history of jewelry that borrows the form of a wheelie suitcase, but replaces the actual case with a block of acrylic resin in which a rat has been embalmed, its death rictus gripping a very large and sparkling diamond — another piece that resonates ironically in the current crisis (it can be yours for just 40,000 euros).

-

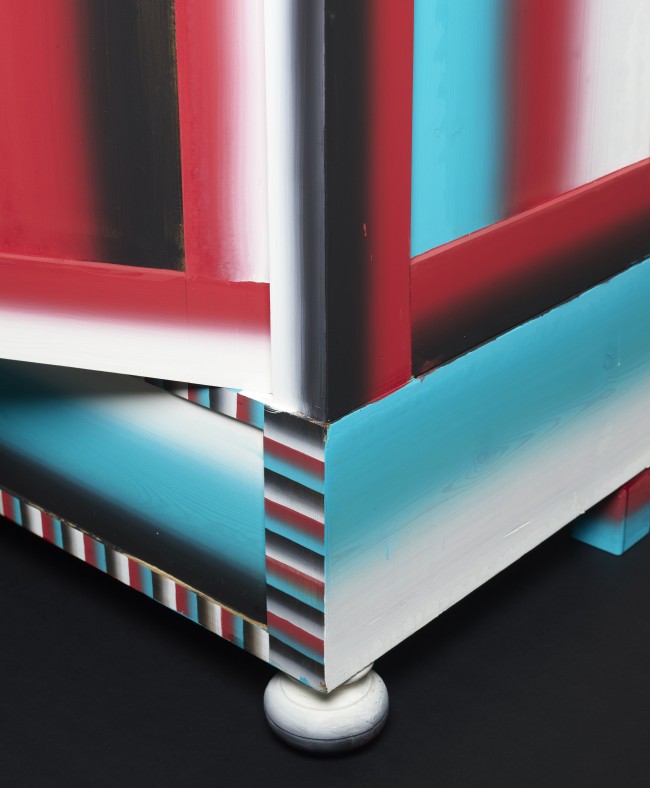

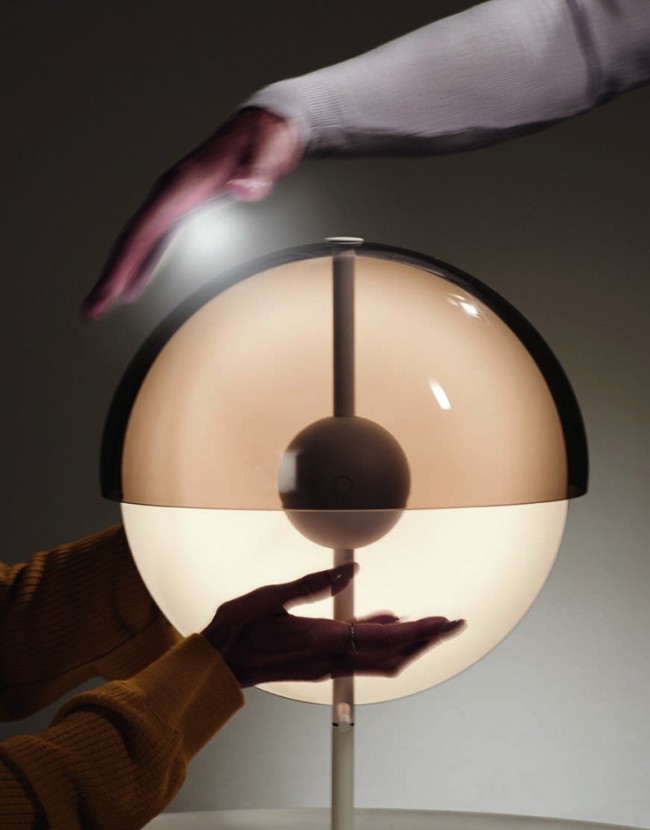

MANIERA 21: Tangible Abstraction, an exhbition by Bernard Dubois and Isaac Reina at Maniera gallery in Brussels, Belgium. Photography by Jeroen Verrecht for Maniera.

-

MANIERA 21: Tangible Abstraction, an exhbition by Bernard Dubois and Isaac Reina at Maniera gallery in Brussels, Belgium. Photography by Jeroen Verrecht for Maniera.

-

MANIERA 21: Tangible Abstraction, an exhbition by Bernard Dubois and Isaac Reina at Maniera gallery in Brussels, Belgium. Photography by Jeroen Verrecht for Maniera.

-

MANIERA 21: Tangible Abstraction, an exhbition by Bernard Dubois and Isaac Reina at Maniera gallery in Brussels, Belgium. Photography by Jeroen Verrecht for Maniera.

-

MANIERA 21: Tangible Abstraction, an exhbition by Bernard Dubois and Isaac Reina at Maniera gallery in Brussels, Belgium. Photography by Jeroen Verrecht for Maniera.

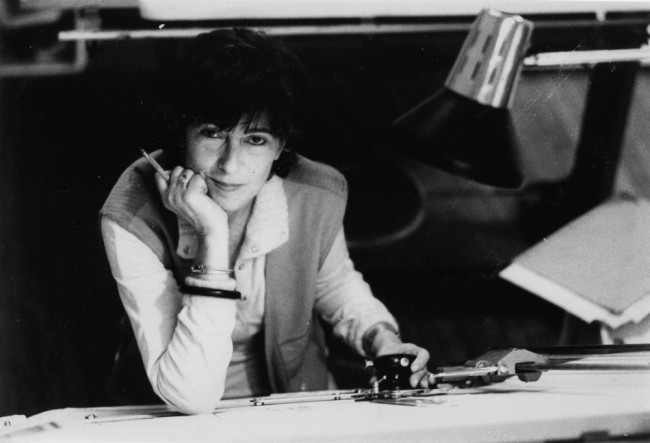

For Collectible’s founders, Clélie Debehault and Liv Vaisberg, one of the fair’s strengths is its inimitable blend of the international and the local, with around half the exhibitors hailing from the Belgian scene. Among them was the excellent Maniera, whose gallery is just a couple of blocks away on Brussels’s Place de la Justice. While Maniera usually mixes genres by showing furniture designed by architects, they’re currently mixing things up further with a new collection dreamt up by architect Bernard Dubois (who studied photography before going to architecture school) in collaboration with leather-goods designer Isaac Reina (who studied architecture before coming to fashion). “Maniera approached me to team up with a fashion designer,” explains Dubois, “and since we’d got on so well working together on his Paris store, I immediately thought of Isaac. He’s just as fussy and obsessive as I am!” Derived from the furnishings designed for Reina’s 2018 rue Bonaparte boutique, the Maniera collection features eight pieces — a folding screen, a desk, a folding table, a low table, two chairs, a tablet, and a lamp — that mix simple, almost art-deco geometry with exquisitely immaculate leather finishes in matte black, patent black, and soft natural hide (or you can have them all in solid oak if you prefer). “There are straight lines and curves, but each time there’s an asymmetry and disequilibrium that we found interesting,” continues Dubois. “Your perception of each piece can change radically depending on your viewing angle,” he says of the almost Cubist tension between 2D and 3D that reaches its apogee in what looks like a wall sculpture, until you realize you can unfold it for use as a table top. All of Reina’s savoir-faire comes into play here, not only in the miraculously seamless leather finishes but also in the super-strong fabric hinge that was originally developed by Louis Vuitton for its steamer trunks. And it’s this hybrid eclecticism, not only in genres and disciplines but also in references — “Some pieces look like they could be derived from the Villa Savoye, others are somehow more Pop,” muses Dubois — that underpins the conceptual complexity of this elegantly and deceptively simple collection.

-

Artifacts from the exhibition 7 ARTS: AVANT-GARDE BELGE (1922-1928), on view at CIVA Brussels until August 9, 2020.

-

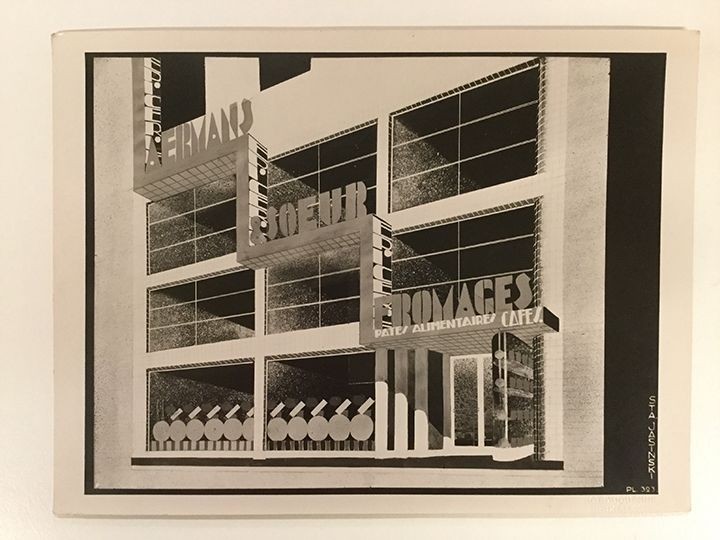

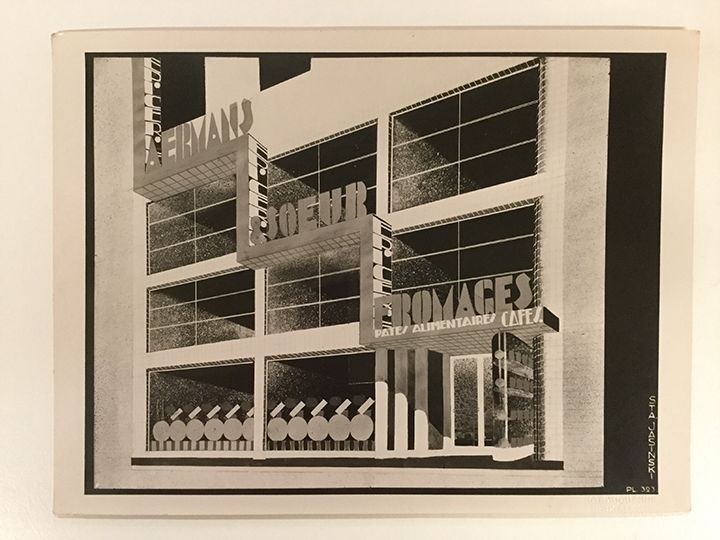

St Jasinski (1901–78), shop front design, grocery store “Epiceries Aermans et Soeur. © Photo Duquenne, courtesy CIVA Brussels

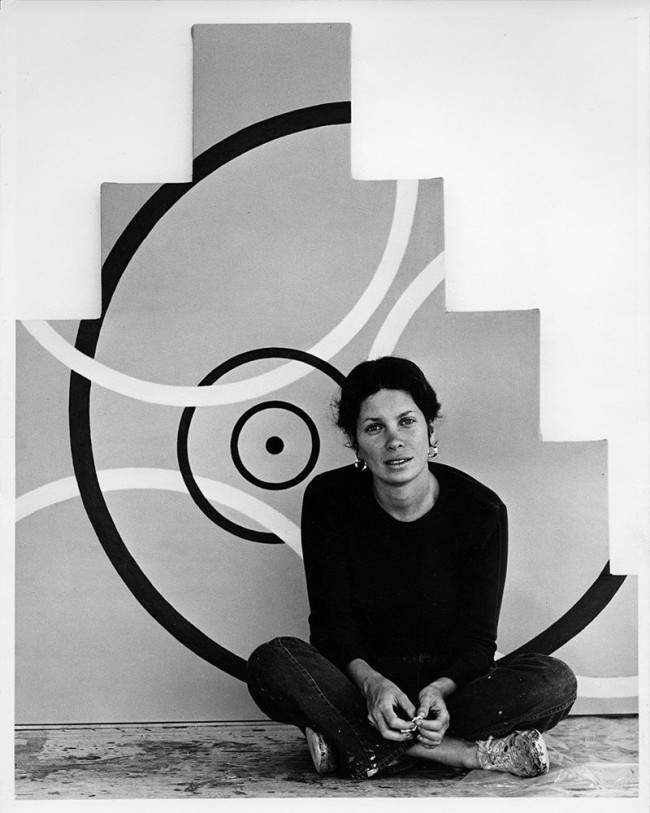

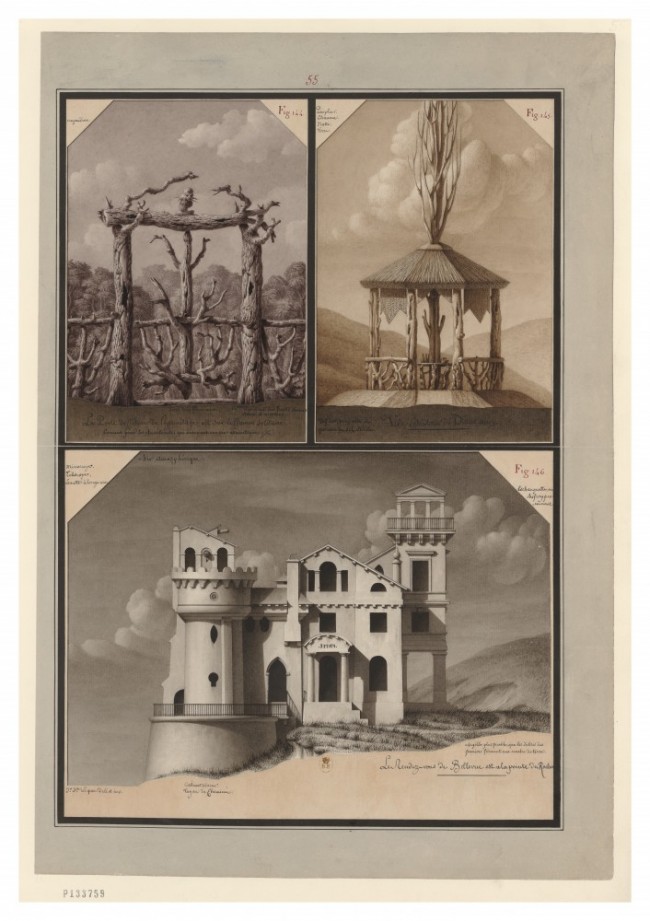

Of course an eclecticism of genres is hardly a new idea, as the exhibition 7 ARTS: Belgian avant-garde, 1922–28, which opened the same week as Collectible at Brussels’s CIVA architecture center, makes abundantly clear. Founded in 1922 by the architect Victor Bourgeois, his poet brother Pierre, and the painter Pierre-Louis Flouquet — who were soon joined by the composer Georges Monier and the painter, engraver, and furniture designer Karel Maes — 7 ARTS was a weekly newspaper that ran for six years, until late 1928, and aimed to cover all seven of the then-recognized arts — including that thrilling new-fangled one, cinema — with a “vast objective” in sight: “ALL THE ARTS. And through them, their penetration in every aspect of individual and collective life,” as Victor Bourgeois wrote in the architecture manifesto he published in the very first edition. The pillars of the seven arts, the two that would allow all the others to be combined, were cinema and architecture: “ART HAS LEFT THE CITY,” the editors proclaimed in the same inaugural issue, “our prodigious urban, industrial, exciting life. It must be brought back. We believe that domestic architecture and cinema will succeed in this.” Although they never used the rather Wagnerian term (too connotated no doubt), they were seeking nothing less than to turn modern life into a gesamkunstwerk in which art, commerce, industry, architecture, urbanism, advertising, music, sport, and just about everything else would form part of a genre-busting whole that abolished any hierarchy between the “decorative” and the “fine” arts. In this aim, they were arguably no different to their Art Nouveau forbears, but their approach was: where Art Nouveau sought to bring nature back into the industrial city in a bourgeois market-economy overkill of curvilinear decorative detail and general fussiness, the 1920s avant-garde sought restraint, asceticism, orthogonality, and rigor, with bold splashes of flat color to brighten up their brave new world. As Victor Bourgeois wrote in his architecture manifesto, “Penury” — the penury of materials in the postwar context — “is the salvation of architecture.”

Although the paper was based in backwater Brussels, it seems that everyone read 7 ARTS, from Le Corbusier to Walter Gropius to Marinetti. Which makes it all the more strange that 7 ARTS has been almost completely forgotten, a fate that the CIVA show attempts to reverse by gathering together a host of designs, artifacts, and artworks produced by artists who were members of or close to the core five. The protagonists’ great youth — of the five, all were 25 or under in 1922, bar Monier who was already 30 — perhaps accounts for a certain charming naïveté and provincialism in a lot of the work, but there are some gems nonetheless: film director Charles Dekeukeleire’s 1927 Combat de boxe, which uses solarization, superimposition of negatives, fast cutting and a whole host of other tricks to capture the choreographed poetry of the boxing ring; Maurice Gaspard’s gorgeous carpet for Dekeukeleire’s home; the subtle abstract compositions of painter Felix de Boeck; architect Stanislas Jasinski’s exhilarating axonometric and perspective drawings and watercolors of various (mostly unbuilt) projects; or Victor Bourgeois’s early attempt at workers’ housing, the Cité Moderne in Berchem-Sainte-Agathe (1922–25). There was a strong social aspect to the “plastique pure” that the group sought to promote, the idea that cost-cutting through both standardization and “radical simplicity” was the only way to produce a truly democratic art — the opposite of art for art’s sake, which they saw as individualistic and bourgeois. It’s a reminder of a time, in the aftermath of the apocalypse of the Great War, when avant-gardes believed that a new world could and must be made. (A situation not without parallels to today’s environmental and pandemic crisis.)

-

Vjenceslav Richter's Yugoslavia Pavilion at the 1958 World Expo in Brussels. Courtesy Rika Devos.

-

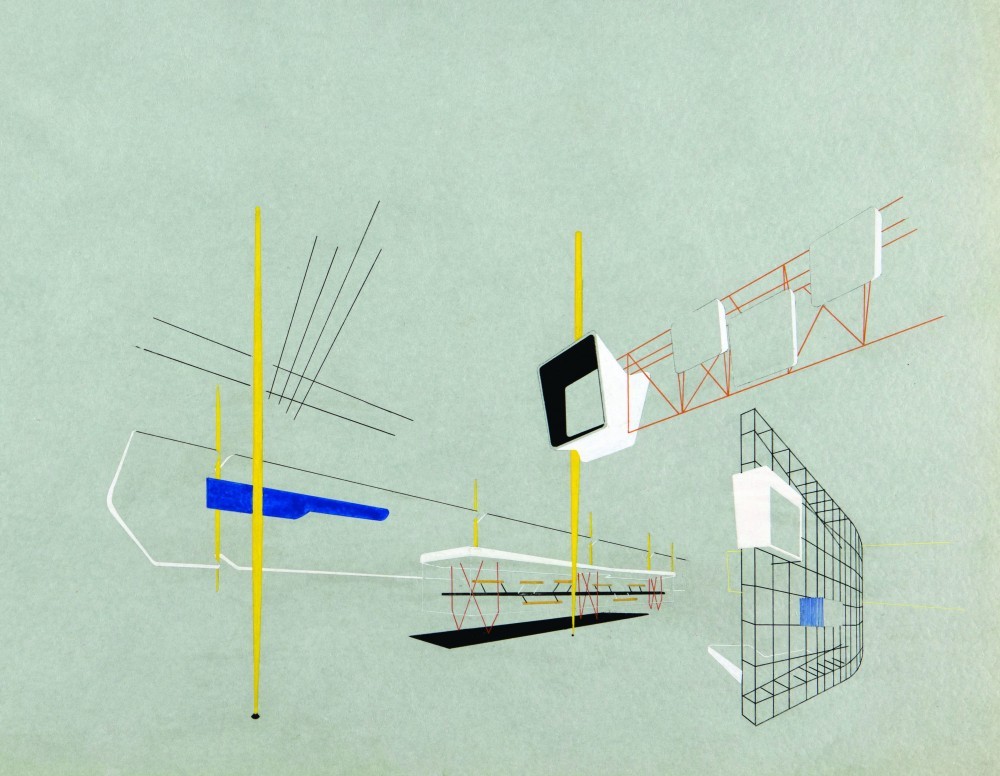

Vjenceslav Richter, Aleksandar Srnec, and Zvonimir Radić's design for the Yugoslavia Pavilion at the 1950 World Expo in Paris. Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb.

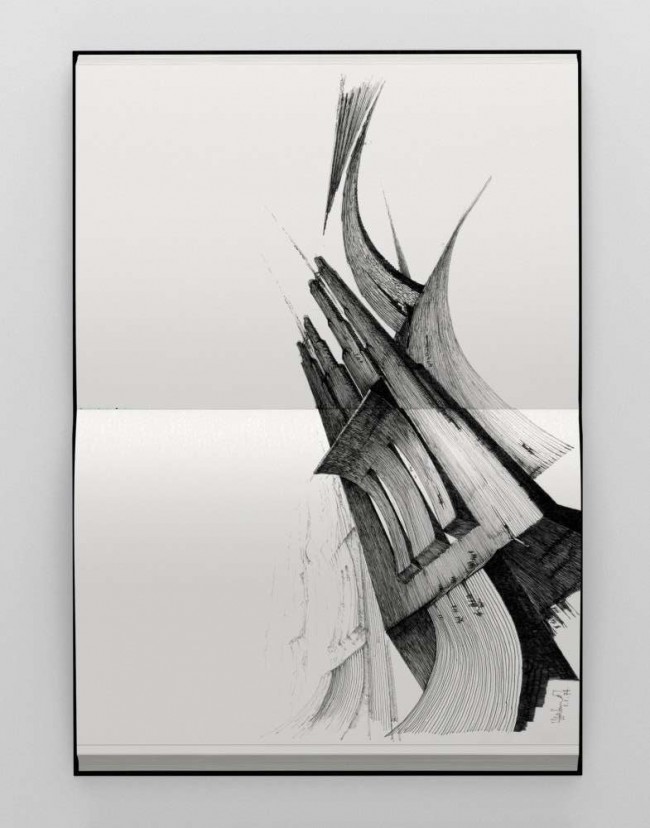

Synthesizing all the arts in a life-sized whole was a dream that fueled many an artistic movement in the first half of the 20th century, and it could still be found either side of the Iron Curtain in 1950s Europe, with the likes of France’s Groupe Espace or Yugoslavia’s EXAT 51. The latter, building on the legacy of Russian Constructivism, the Bauhaus, and De Stijl, sought a renewal of society through abstraction (rather like 7 ARTS), and included among its members the Croat architect — but also urbanist, painter, sculptor, graphic designer, stage designer, and furniture designer — Vjenceslav Richter (1917–2002), who is currently the subject of a retrospective at Brussels’s BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts. So determined a genre-buster was Richter that he invented a whole utopian concept of “Synthurbanism” in the 1950s and 60s, “a theory of an autonomous city,” as the curators describe it, developed as part of a “search (for) a synthesis of the arts, of man as a unit of measurement, and of the creation of a polyfunctional urban structure.” While the monumental drawings he produced in this quest are a highlight of the show, it’s not for Synthurbanism that Richter is chiefly remembered, but more for the series of international pavilions and exhibition spaces he designed for the Yugoslav state, of which the most celebrated, accomplished, and downright beautiful was the national pavilion at Brussels’s Expo 58 (now used as a high school in the small Flemish town of Wevelgem). A steel-and-glass miracle of light and levitation, the pavilion is testimony to another postwar search for a socialist utopia driven by an unshakeable belief in a better future. What future roles will art and architecture play in the quest for a fairer new world in 2020? Are post-apocalyptic gender-inclusive trash blobs the answer? Or, in our sophisticated and jaded age of algorithms, irony, and end-of-times pessimism, could a conscious effort at unalloyed optimism be about to make an unexpected comeback?

Text by Andrew Ayers.

Images courtesy Collectible 2020, unless noted otherwise.