Dreams of Modularity: Bernard Dubois’s Ligne 102

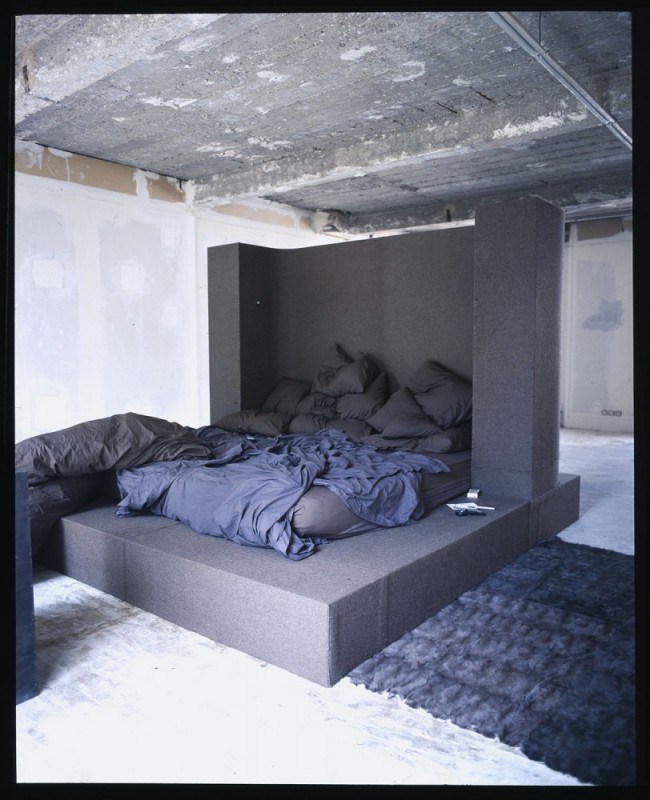

Ligne 102, a series of modular objects designed by the young Belgian architect Bernard Dubois, inhabits a world suspended between solids and voids that exchange places, where straightforward architectural tectonics encounter shifting elements of combinatory design, and the most hard-edged geometrical forms are conjugated with the most muffled, aural, and auratic of all construction materials: cork. In Ligne 102, Dubois deploys strategies of modular composition that simultaneously adopt and undermine normative conventions. These strategies are derived from a restricted, seemingly arbitrary, but deeply encoded repertoire of historical precedents. Exhibiting resemblances that cut across inherited, albeit discontinuous, narratives of architectural history — Alberti’s Palazzo Rucellai, the pictorial universe of Giorgio de Chirico, Ricardo Bofill’s La Fábrica, or Eduardo Chillida and Luis Peña Ganchegui’s Plaza de los Fueros in Vitoria — they register compelling points of intersection between spaces and times from the past whose reanimation is made visible, constructs that emerge in the design process, and functions evoked by both.

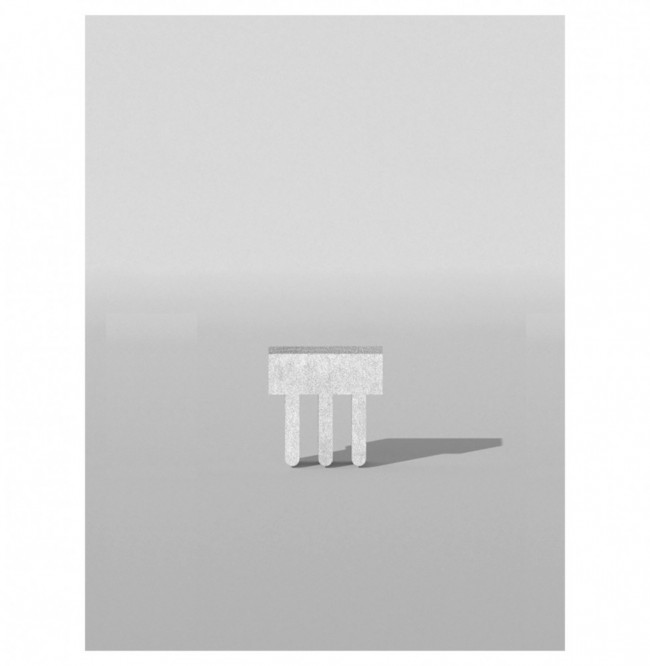

The formal (and historical) precedents inherent to Ligne 102 are decomposed to yield basic geometric forms, fragments of architectural discourse that are generic in themselves, without any truly individual features. These coded, yet also neutral, elements are then combined to form perforated walls, floors, desks, and chairs, each with a memory trace of their architectural origin embodied in their tectonics.

With respect to Ligne 102, Dubois’s practice is rooted in two hypotheses: first, that constituent geometrical elements of design are wholly contingent to the spaces they occupy, and second, that they can become the actual, tangible building blocks of functional units, and can define their essential, if always flexible, parameters.These design environments and their accompanying functional objects, made up of a shifting array of arches, pillars, bridge-like structures, trusses, pylons, beams, and support systems, are poised between memory and anticipation, between a vision of oneiric transformation and eminently reasonable logics of fabrication. Though fixed for our viewing, Ligne 102’s uniquely formed environments and objects can be decomposed and recomposed at will.

What Dubois has created with Ligne 102 is a variable ensemble of interior scénographies motivated by a deep historical sense and a logical repository of constructive elements. In this way Dubois produces ephemeral yet also memorable configurations. Though muffled, these designs speak of just such a dream of the decomposable past as a new blueprint for the recomposable present, reversing our usual expectations about the echoes in the chambers in which our daily lives are played out, as we remember objects and experiences past and dream of what might just be around the recomposable corner.

It is not only that Dubois thereby repositions Marcel Proust’s project of literary memory with each shift in Ligne 102’s apparatus of flexible geometrical elements; he also shifts the rules of the contemporary design game by introducing fragments of syntax from the historical narratives of architecture, mixing up what we once thought linear, fixed, and established. More precisely, Dubois recalls and refashions the memory-generating image of Proust’s famous cork-lined room, so that it is able to encompass all of architectural history in a relatively small workspace. À la recherche du temps perdu, Proust’s canonical collection of novels, would have been unthinkable without that nearly mythical cork-lined chamber, a hermetically sealed refuge for the neurasthenic, long-winded writer. (Its address, 102 boulevard Haussmann, is of course echoed in the name Ligne 102.)

By allowing potentially all of us access to the cork-lined room, Ligne 102 makes possible a new order of memory in the fields of architecture and design. As in Proust’s novel, an epic dimension of space and time rubs elbows with the most closely observed and seemingly insignificant details, so that when the two levels come together, new forms of meaning are produced. In this way individual and collective planes of memory meet in a single design strategy, providing a new space for their sudden redefinition. Like a renewed erotic fable of the love between objects, not without Surrealist overtones, Dubois places us in a metaphysical arena of conjunctures where every form of attraction and repulsion becomes possible, where new objects form, reform, and decompose in a choreography of jostling reconfigurations.

Text by Daniel Sherer.

All photographs by Vincent Dilio for PIN–UP.

Video by Charlotte Miller.

Dr. Daniel Sherer teaches history and theory of architecture at Princeton University School of Architecture. His areas of research include modern receptions of the Classical tradition, Italian Modernism, Italian Renaissance and Baroque architecture, contemporary architecture, historiography and theory, and contemporary art, frequently in relation to architecture. Last year he curated the exhibition Aldo Rossi: The Architecture and Art of the Analogous City, at Princeton University School of Architecture.