RICARDO BOFILL: Architecture’s Dazzling Chameleon Reveals His Many Colors

While most architects spend a lifetime perfecting a signature style, Ricardo Bofill seems to avoid it at all cost. The fascinating 69-year-old Catalan is perhaps best known for the Postmodern public-housing projects he built in France in the 1980s, but his oeuvre spans several decades and creative periods that range from Surrealist-inspired multi-color beach resorts to the glass-and-steel extravaganza of Barcelona Airport’s brand-new Terminal 1. On my way to our meeting in the Barcelonan industrial suburb of Sant Just Desvern, we drive by a strange-looking 16-story apartment complex, whose semi-circular balconies seem randomly stacked onto the terracotta-colored façade, making it appear like a living organism. “This is Walden 7,” my cab driver screams excitedly, “It was built by the architect Ricardo Bofill!” When I tell her that is who I’m going to see, she gets even more excited: “He used to be married to Julio Iglesias’s daughter,” she says, in fact referring to his son, Ricardo Bofill Jr., who works as an architect alongside his father (and has an ¡Hola!-worthy marital record). But the little mix-up doesn’t really matter — it just goes to show that in his native Spain, and especially in Barcelona, Bofill is a household name.

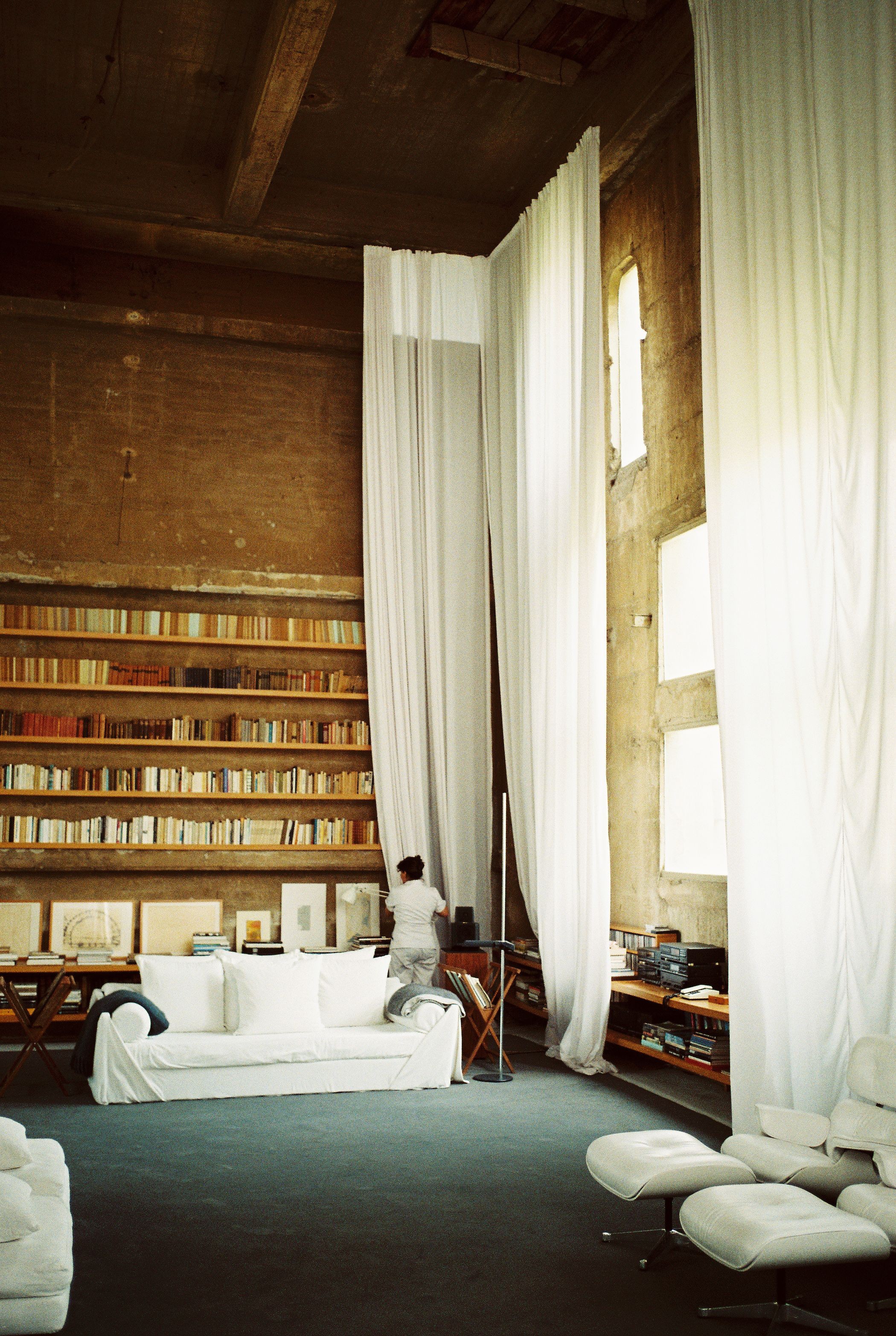

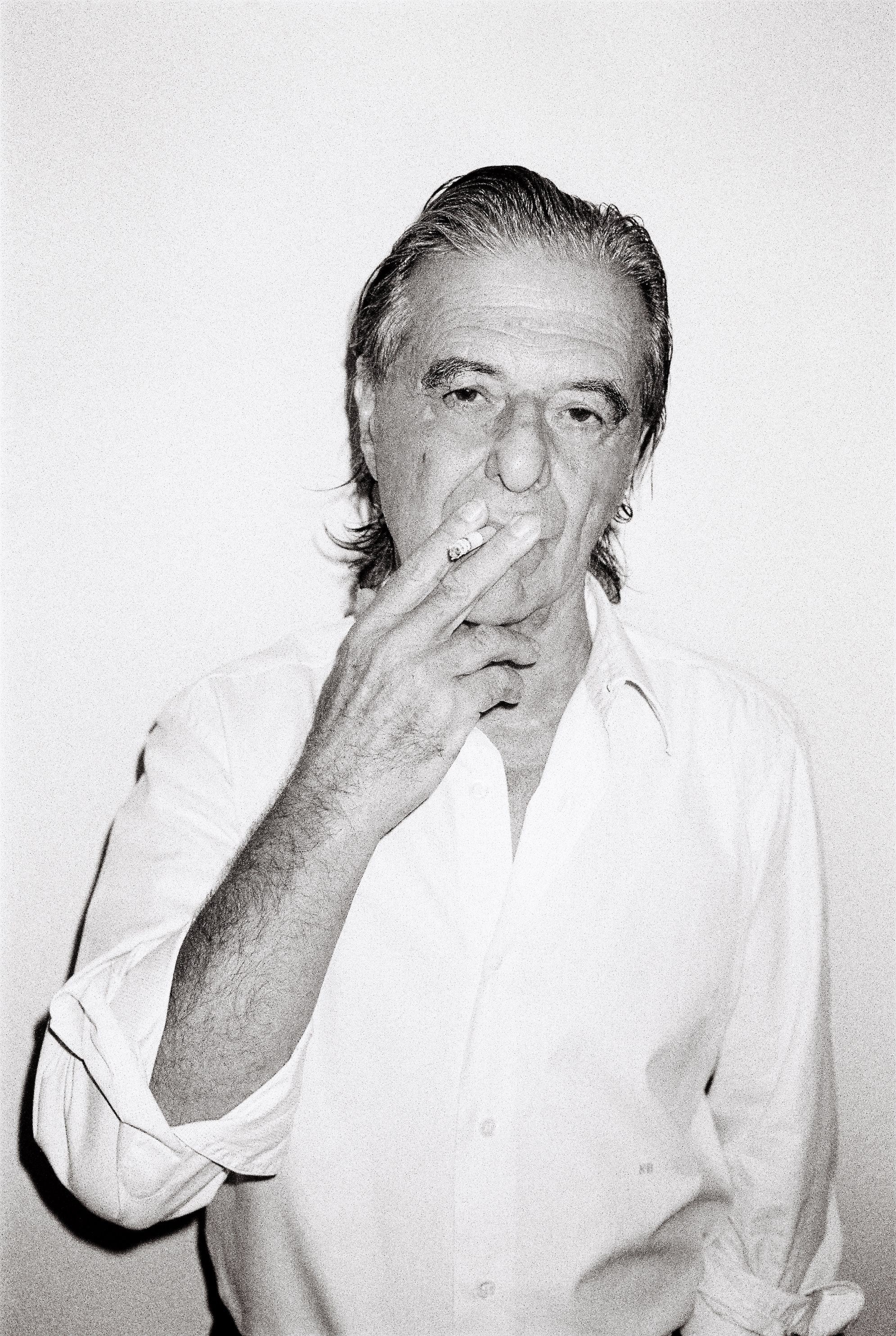

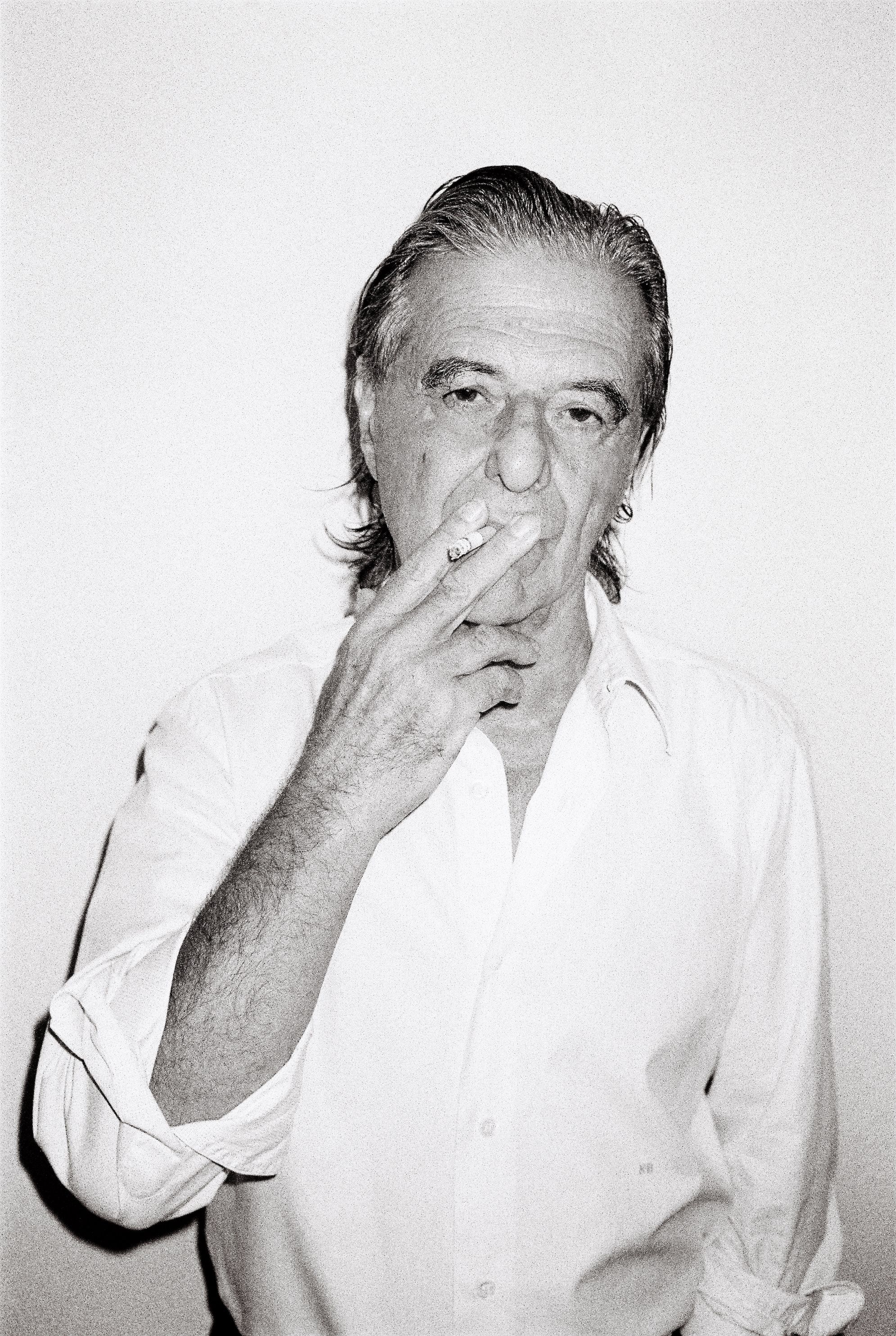

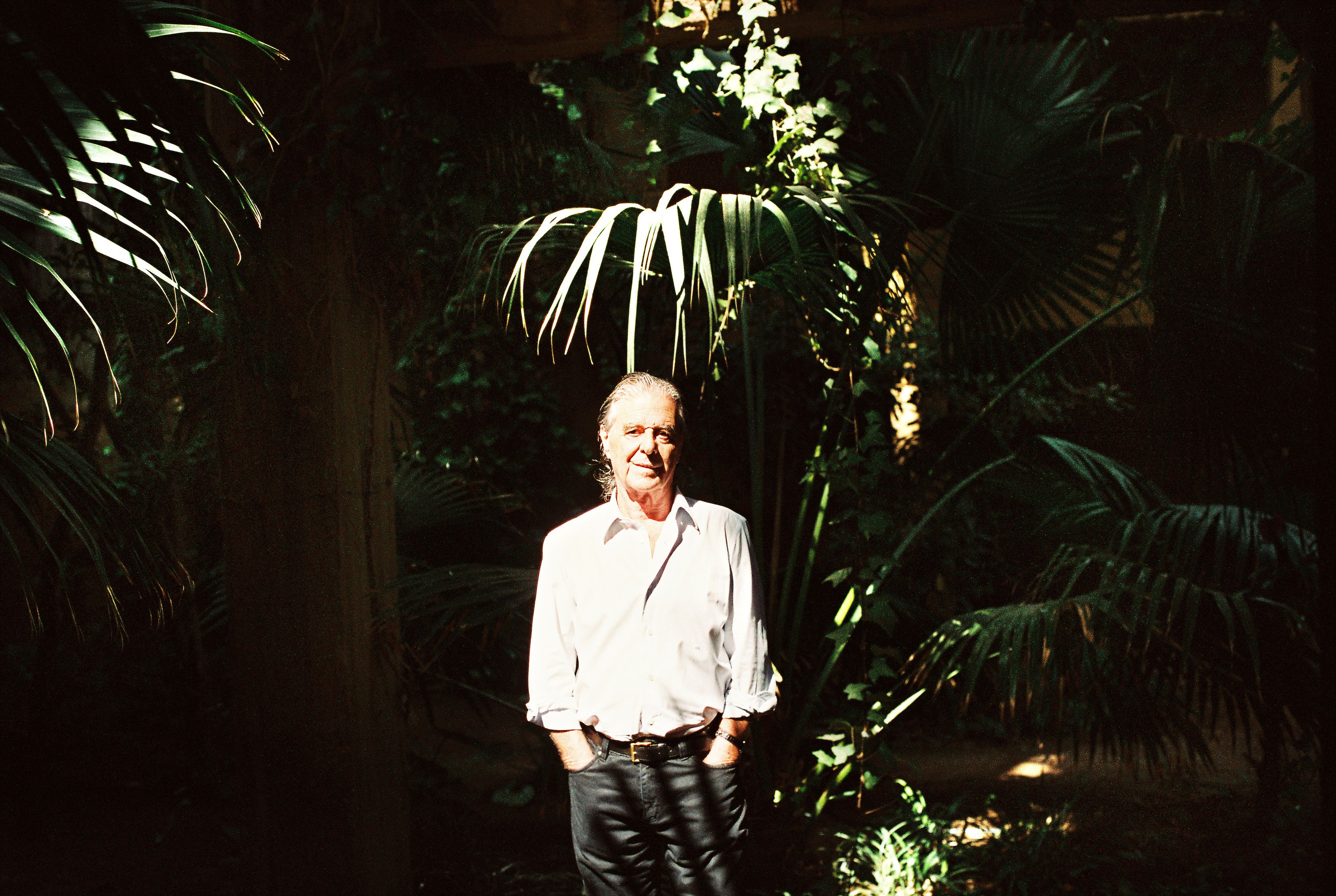

Taller de Arquitectura, as his office is formally known, is located in a former cement factory, which Bofill bought almost 45 years ago and has transformed over the years into a palatial office and living compound resembling an overgrown medieval castle. His apartment is on the top floor, with breathtakingly high ceilings and a rooftop garden (without handrails) enjoying a direct view over Walden 7 on the adjacent lot. A handsome Bofill, in crisp white shirt and black jeans, greets me in a clover-shaped office (four former cement silos knocked together). During the one-and-a-half hour interview at his square desk, he smokes at least half a pack of Marlboro Lights while jovially talking about his early days as an architect, the steady changing of style in his career, and why he hates institutions and loves Catalonia.

La Fábrica. Photographed by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

Felix Burrichter: Converting these premises into offices was one of your first projects I believe?

Ricardo Bofill: Yes, it was a disused cement works, I was 24 and it was a very cheap neighborhood; I’d already built houses in Barcelona and wanted to jump up in scale. At that time I’d developed a different working method. I was already interested in a different architecture — I didn’t like Le Corbusier, I didn’t like Gropius… I was interested in Spanish vernacular architecture, architect-less architecture. And the buildings I designed at that time, like in Sitges, where I built modular housing (Kafka’s Castle, 1968), or in Alicante (Xanadu and La Muralla Roja, 1965), were greatly inspired by the vernacular architecture of southern Spain and North Africa.

You studied in Barcelona and Geneva, right?

Yes, first in Barcelona, and then I went to Geneva because I was thrown out of Barcelona University for belonging to a left-wing student movement. It was at the time of Franco… I stayed two years in Switzerland, and afterwards moved to Paris. And then at one point I decided to go back to my father in Spain. He was an architect and builder, and was building a lot, which allowed me to build very early on — I completed my first house at the age of 19 (in 1960), when I was still a student in Geneva. It was a little holiday home in Ibiza. One of my first projects with my father was a series of town houses built with no money, with cheap local materials such as brick. There was nothing in Spain back then, it was a very poor country.

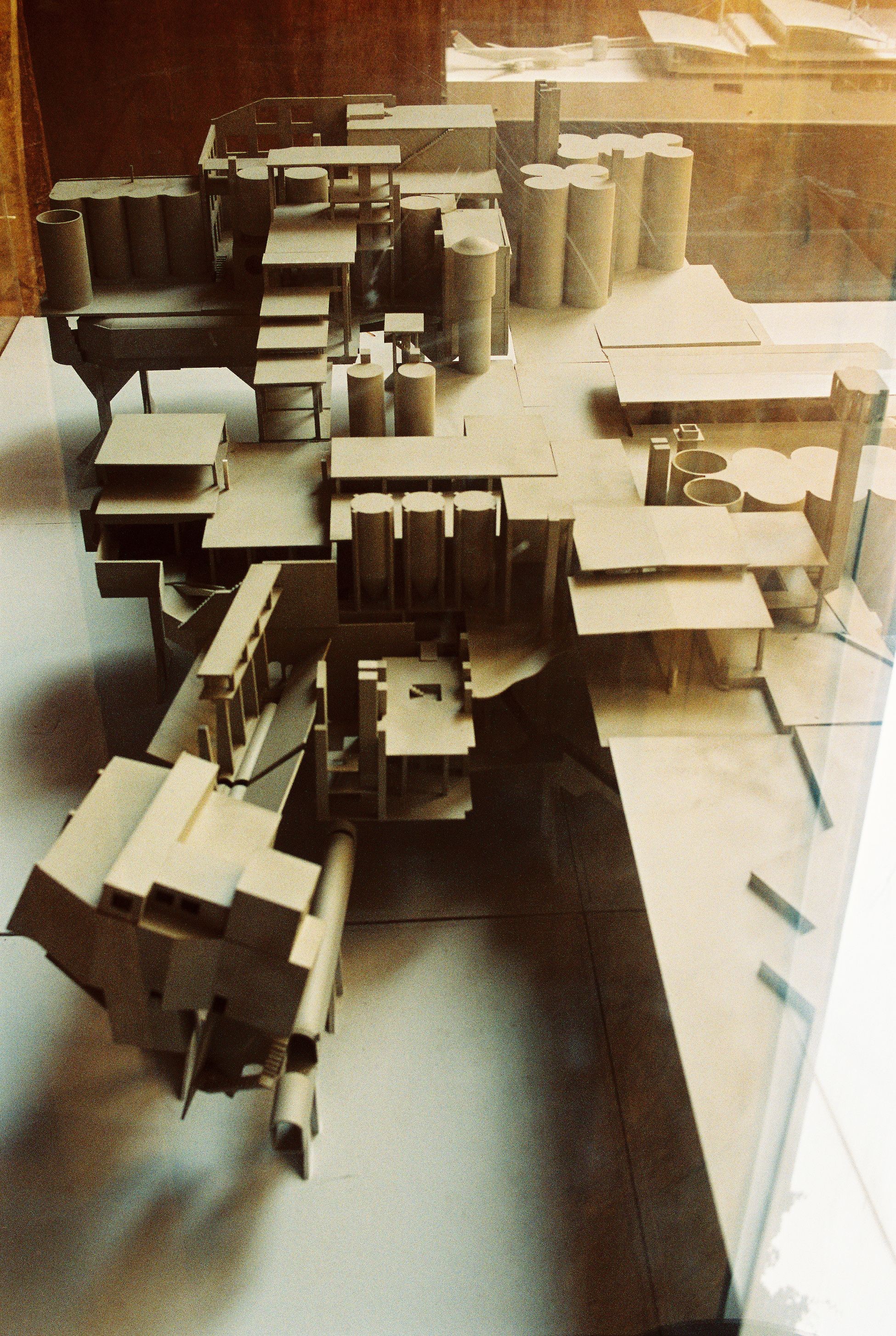

And afterwards I thought about reworking the process of architecture, and of volume, and I carried out a series of experiments. Then, in 1968, we did a series called “the city in space,” which was an entire conception of the city, a break with the rationalist bloc, a break with the cheap architecture that was being built in Spain at the time. We conducted two experiments, one in Madrid, which was banned by the Franco government, and another, which was the culmination of our research, was Walden, which we completed in 1974. The idea for our housing was based on a modular system, because for me the concept of the traditional family unit, with a father, mother, and two children, is just one case among others: one can also live alone, communally, or in a homosexual couple, for example. The idea was that you could buy one module, two modules, three modules, or however many you needed, horizontally or vertically. It was really a whole other way of imagining urban life and an experiment in communal living. But with Walden 7 it was kind of the end of my research into that. But it was also during this period that I undertook research into the conversion of old ruins, and that’s when the conversion of this cement works happened. It’s fantastic because it preserves the memory of industrial architecture… Afterwards we spent two years cutting things out, taking away various elements, and then we had to put windows in, and there was already a desire to introduce a historicist architecture — a Catalan architecture, but transformed. Then we gave it a Brutalist treatment, and there are also the Surrealist elements we left in, all of which correspond to the different periods of my history.

La Fábrica. Photographed by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

You said earlier that when you left university Le Corbusier’s architecture didn’t interest you…

Not only did it not interest me, I was totally against it! I was quite radical when I was young, and for me Le Corbusier and co. were responsible for all the sorry housing projects in Europe and especially in the Soviet bloc. Dividing the city into functions; treating houses like machines — the urban solutions put forward at the time seemed anti-urban to me, the simplification of the city into something other. And I’ve spent my life hating this Modern Movement and trying to find alternatives, trying out other solutions, trying to bring back the spirit of the Mediterranean town, the European town, the mixture of functions, the mixture of spaces, the street, the square, the mixture of social strata.

There were no contemporary architects who inspired you at that time?

At the time there was only Louis Kahn and Alvar Aalto, and to a certain degree Frank Lloyd Wright. But for me Le Corbusier was the devil! For example, the plan he drew up for Barcelona was just absurd. He was certainly a man with enormous talent and extraordinary force, but his ideas were pretentious and totally monstrous — I think that at bottom he was an evil person.

Your projects in the late 60s and early 70s have a Surrealist element to them.

Yes, absolutely. At the time, each new project was a try-out for me. In that period, we didn’t want to define the final form in advance, but instead let the process produce the project. Each project was different because we didn’t necessarily want to produce “beautiful” projects. So we experimented with processes: for example, in plan, the value given to layout-forming elements, or the use of space, or construction materials — we never wanted to predetermine the final result, a bit like, as I was saying earlier, in vernacular architecture. Another big influence was Antoni Gaudí: I’ve always been greatly inspired by Catalan architecture, and there’s obviously no way around Gaudí! He was a genius! But what I learnt from him wasn’t the Gaudí style, but his vision of architecture. He was a man who never repeated the same door twice, the same two windows. No! He innovated constantly, and refused repetition. A simple man, but an inventor. He started out as an anarchist, and finished as a visionary traditionalist. So, according to Gaudí, one must never repeat the same door twice. But that’s impossible today, we no longer have the same craftsman resources. I transferred that to a contemporary context by saying to myself: “I must never repeat the same two projects. Each project must be different!” That’s the great lesson of Gaudí. Moreover, when they began work again on the Sagrada Familia, they asked me if I wanted to do it, and I said, “No, it’s impossible. If you have a painting by Picasso, you can’t continue it if it’s unfinished!”

Another great influence for me was my journeys to Italy, and the study of Italian-Renaissance architecture: Alberti, Brunelleschi, etc. So here we spent nearly ten years with a research team on what you might call our Classical period, which others have called Neoclassical; but actually that’s not true, it’s a modern Classicism, it’s a Classicism with another function, with other materials, with another idea, trying to recreate squares, streets…

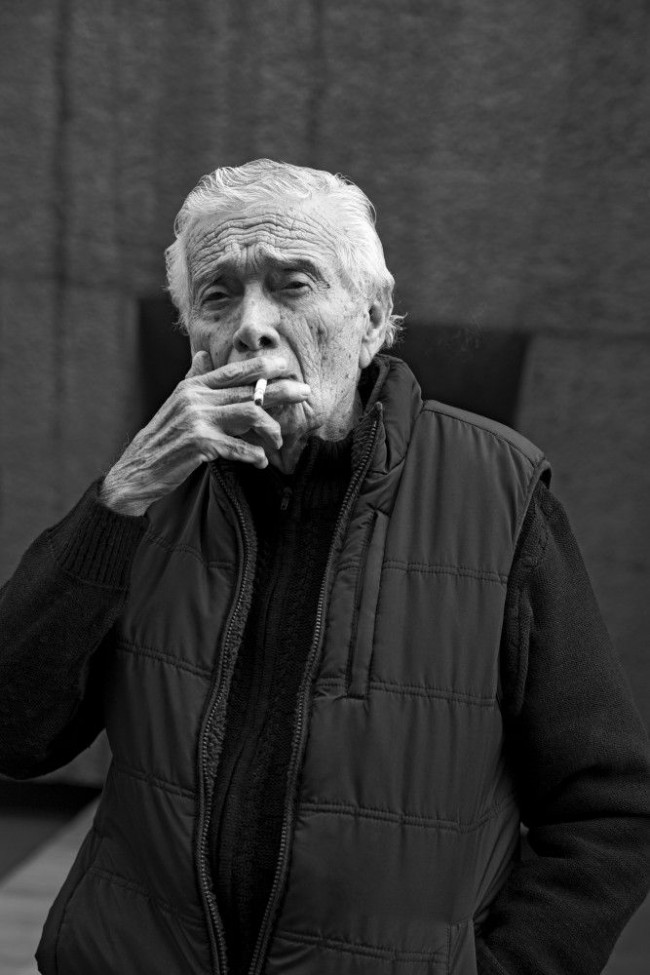

Ricardo Bofill photographed by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

How did the transition occur from vernacular architecture to experiments like Walden, and then to what you call modern Classicism?

Walden 7 was, if you like, a critical response to the entire Catalan, and even European, intelligentsia. It was a critical response because we said: “There! It’s a monument in the middle of suburbia, a vertical monument in the suburbs!” And straight away there were critics who said: “One cannot experiment with social housing, with architecture for the poor.” Because Walden 7 was a social-housing project you know, although it isn’t any more because there is a law in Spain to the effect that after 20 years buildings lose their social-housing status. But at the time that’s exactly what it was, it was a building populated with people of all varieties: transexuals, junkies, singers, writers, unemployed people… It was a very interesting mixture. But greatly criticized. But I was expecting that, because I’d put all my research, all my experimental ideas, everything I was talking about earlier, into one single building. I exhausted myself intellectually with Walden, and it’s then that I changed. And I tried, with a team of around 20 people, working “word by word” to learn and acquire all the different architectural languages possible. Once I’d studied Classicism, once I’d studied all these architectures, the culture and language of a building became a secondary element. And above all a non-ideological element, because — especially at that time — if you didn’t produce a certain architecture you were a reactionary. Architecture was very ideologized, aesthetics had become something ideological, but I wanted to erase all that. For example, there are great writers, like Céline, who was rather rightwing, and who was a very good writer, or those like Borges, who write in a totally formal, classic way and are very good, and then there are the “nouveaux romans,” which are nice, etc. Personally I think one should know all the different writing styles in order to be able to use them in each particular case one sees fit in the manner one wishes. At the time I hadn’t yet learnt this freedom that allows one to change, evolve, and write in a different way with architecture.

-

La Fábrica. Photographed by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

-

La Fábrica. Photographed by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

-

La Fábrica, Ricardo Bofill's home and office. Photographed by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

So what was the project that followed Walden 7?

After Walden 7, I went first to Algeria and then to France. In France I proposed a housing scheme in Cergy-Pontoise which we called “La Petite Cathédrale” (1971). It was a French-style Walden if you like, because the French had more advanced techniques for building mega-structures. But it was never realized. And then, on the other hand, in Algeria I built an agricultural village (1980) entirely in brick, which was a very, very inexpensive construction.

Interestingly, it was at the same time as Postmodernism — you could say that I was one of the creators of Postmodernism. Why Postmodernism? Because architects were starting to say to themselves that the International Style was an architecture with a very narrow vocabulary. And what I said at the time was that the architectural debate needed to be opened up, that one should be able to write with more than just one language. What’s funny is how much, after Postmodernism became the official style in America, it didn’t interest me anymore, because there was no longer an idea behind it, it was just an aesthetic choice. Each time we started a movement — and I was at the beginning of a lot of movements — its popularization was very rapid, too rapid, so the architecture became banal and the whole movement became banal, so I had to get out. I don’t like institutions. For example, each time I’m asked to join the academy in France, I say, “No thank you.” I don’t want to be part of an academy, what interests me is invention, and reinvention. Mine is a very different career to other architects’, important architects at least: I run into them from time to time, but I go another way, because I’ve got other ideas, another life strategy. What interests me is learning, getting to know the world — from Sweden to Africa — in a different way. And architecture allows me to get to know the world differently. When I’m in Chicago and I look at the world I’ve a different view from when I’m in Tokyo or Beijing. It’s rather a kaleidoscopic view. You know, no general theory works for everything — neither for architecture, nor for economics, nor for politics. Each application (of it) will become corrupted along the way…

Ricardo Bofill at his office in La Fábrica. Photographed by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

If you were to give names to the different periods in your oeuvre, what would they be?

I’d call the first period “critical realism,” because we were working with limited means, very small budgets, local projects, in brick, etc. The second period was the period of research into our working methodology, or working processes, up till Walden 7. Afterwards there was an almost Postmodern period, at the beginning of Postmodernism… which brought me to this modern Classicism I talked about earlier. That lasted ten to 15 years, I had a lot of work, and now we’re in an architecture where we’ve already had all the influences and a certain knowledge of the world, which can always be deepened. But now it’s an architecture that tries to adapt… There is a book that marked me a lot, by Christian Norberg-Schulz, called Genius Loci (Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture, 1980). Now we’re in a very eclectic and very globalized period, but as architects what we can’t do is to put up a building in Barcelona, Madrid, or Chicago and then go and transport it to Senegal. You know I’m very into what you might call “poor architecture” … For example, the project in Senegal (Résidence de la Paix, Dakar, 2007) is “social” architecture which costs 200 euros per square meter, but for me it’s the same thing as when I construct a building in New York that costs 30,000 euros per square meter. And right now there’s an economic crisis, which is good in that we are starting to think about economical housing again. Up till now so many architects abandoned social theory in favor of technology and creating unusual objects — the star system, as it’s called. But what is often forgotten is that 90% of construction consists in housing. And the most difficult thing to do is social housing. So now we’re in the process of relearning that, with projects in Africa, India, we’re trying to do things in Latin America, even in Barcelona, very, very, very, very cheap housing, very basic. And in Russia, too. The Russians want to change their entire construction system, as well as their entire prefabrication system. They came to see us because we are very good at doing prefab, so we’re going to build a neighborhood in Moscow soon, for which we’re developing a whole system of prefabrication, because that’s what they want.

The famous Arcades du Lac in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines (1982) or Les Espaces Abraxas in Marne-la-Vallée (1982) were all prefabricated as well, no?

Yes they were, but prefabrication has developed a lot since then. And in Moscow we’re trying to find a new vocabulary in order to be able to pass it on to other architects as well, because we’re well aware that afterwards other architects will be involved. In fact it’s a very industrial job, very tied in with the fabrication system, and very close to the construction industry, so right now that’s where we are. Sometimes we allow ourselves a more pronounced architectural gesture, but it’s much more difficult to do social housing well: the problems of repetition and fabrication, it’s all terribly complicated. Even after all these years it’s still a challenge for me. Recently I’ve been spending a lot of time in cement works, but not this one! (Laughs.)

During your “new Classicism” period, there was a big exhibition at MoMA, with Leon Krier, in 1985, right at the height of Postmodernism. Lots of architects at the time included a sort of irony in their architectural language, as if they were poking a little fun at Classicism. But looking at your work over the years, I don’t see that sense of irony…

All my designs talk about a re-appropriation of signs — signs are re-appropriated and take on a different meaning. It’s more of a Spanish irony, if you like, this re-appropriation of the meaning of things. For example, a Classical column contains a spiral fire-escape staircase. I try to take away the symbolic language that was attached to these things in the past. It’s funny, but in Germany it’s something that has very bad press because there was this whole problem with Albert Speer’s architecture. Speer only produced copies, and bad copies at that. So now, in Germany, they have a bad conscience and are afraid of Classicism, and of gigantism. But for me gigantism isn’t a problem because I come from a liberal left-wing family, so I can say without shame that Terragni, architect to the Italian fascists, was a very good architect. In Germany, it’s still difficult to say that. But in any case, Germany is also a country where they’re not that keen on the city: there’s only Berlin, the others aren’t real cities! (Laughs.)

Ricardo Bofill photographed by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

So the word “gigantic” isn’t an expletive for you?

I’d be more inclined to say monumental, not necessarily gigantic. But even my monumental projects always have a second, human scale. When you go into the new Barcelona Airport terminal, it’s very big, the ceiling’s very high, out of scale — but afterwards there’s always a second scale at human size within this big scale. And in any case, since the modern era we’re living in often gives carte blanche to vulgarity and public space is reduced to the level of merchandise, advertising, and other “values,” the only way to counter that is to make the space a monumental space.

If one compares your recent projects in Spain — like the new Barcelona airport terminal (2009), the W Hotel Barcelona (2009), or the Nexus II building (Universitat Politènica de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2001) — and your recent projects abroad, especially in Russia (“Star Way” complex, Konstantinovsky Congress Center, St. Petersburg, 2007), I’ve the impression that outside Spain clients ask you to repeat things you did in the 1980s, while at home you seem to have evolved to a fourth style period, all in glass, without historicizing details.

Yeah, OK, but don’t forget that clients like asking for what they’ve already seen elsewhere. We’re the last links between Classicism and the modern age. There aren’t any more like us, it’s a fact. That’s why there are a lot of people who come to us wanting that.

Ricardo Bofill's books inside La Fábrica. Photographed by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

Are you often criticized for that by the public?

No, mostly the general public loves what we do.

Do you sometimes return to your large-scale housing projects such as Les Arcades du Lac, the Quartier Antigone in Montpellier (1980 onwards), or Les Espaces d’Abraxas?

Yes, and the residents are happy. We haven’t had any major social problems. But let me tell you something: what hurt me was the “Neoclassical” criticism, especially in France. The French are a people who like to classify everything; after all, they invented the modern dictionary! (Laughs.) Their sticking the Neoclassicist label on me made me very angry, so I went back to Barcelona.

But why does being labeled a Neoclassicist bother you so much?

I hate Neoclassicism! The 19th century in France or Italy was a century of normative, official architecture, and bam!, I find myself stuck with this label. Neoclassicism closed off architecture, it smothered the creativity of earlier eras.

What importance does Catalan culture have for your work, or for you personally, today?

Well, you know, Catalonia is a small, marginal country, but with lots of resources, business people, artists… But, like with all small countries, either you make the effort to get to know the world, to take an interest in what happens outside your own little world — and you have to make the effort that curiosity demands and take the trouble to get to know other cultures — or you die, because no one’s going to come and see you — it’s not like if you were living in New York, London, or Paris. It’s changed a bit since I was young, but Barcelona remains a provincial city. So one must simply convert this lack into an asset — that’s what I’ve learned living here. Catalonia is a small country, but with very varied landscapes, so that also gives you a connection with nature, even if it’s in miniature. There’s the sea, the mountains, etc. And then Catalonia is an avant-garde country: there were always lots of painters, sculptors, architects, designers… There isn’t that nostalgia for the empire that one finds, for example, in Madrid. And that’s also reflected in the day-to-day mentality of the city, even politically: the emancipation of women, the recent legalizations with regard to different lifestyles, like gay marriage, drugs, etc. — these are things that we (in Barcelona) were already talking about thirty, even forty years ago. It’s a country of good professionals, good doctors, good lawyers…

And good architects?

Yes, that too… a bit. (Laughs.)

Ricardo Bofill photographed by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

GET THE ORIGINAL PIN–UP 7 HERE.

Interview by Felix Burrichter.

Originally published in PIN–UP 7, Fall Winter 2009/10.

All photography by Nacho Alegre for PIN–UP.

The images from this story were originally published in PIN–UP 7, Fall Winter 2009/10.