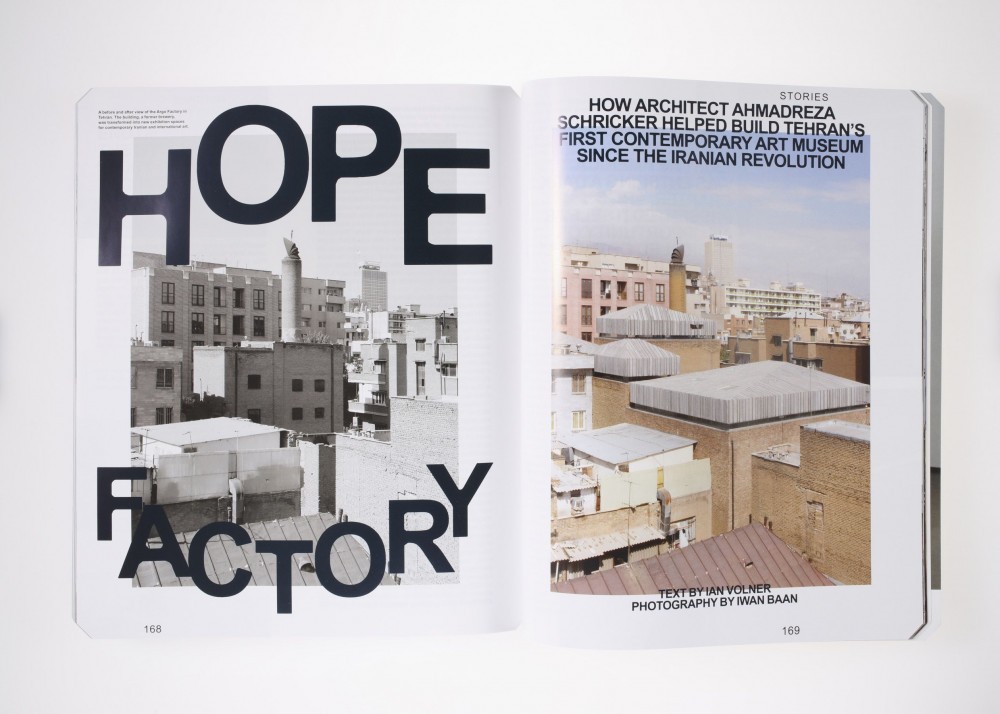

ARGO FACTORY: Tehran’s First Contemporary Art Museum Since the Revolution

At some point in the mid-1960s, an unremembered Iranian general decided he’d had enough of the yeasty, hoppy smells emanating from the brewery that had lately opened across the street from his home in central Tehran. The plant had been built at the behest of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, who was not known for his strict adherence to Islamic temperance. But in the fervid political environment of post-World-War-II Iran he evidently decided to stand by his general. The brewery was closed. “After that, everybody used the building to make their own homes,” says architect Ahmadreza Schricker, principal of New York firm ASA North, pointing at the surrounding structures in a series of recent aerial images. Sure enough, the telltale brickwork of the former Argo beermaking facility is perfectly discernible in a couple of the slender housing blocks on either side of the defunct plant, evidence of its steady cannibalization over the course of the last half century and more.

-

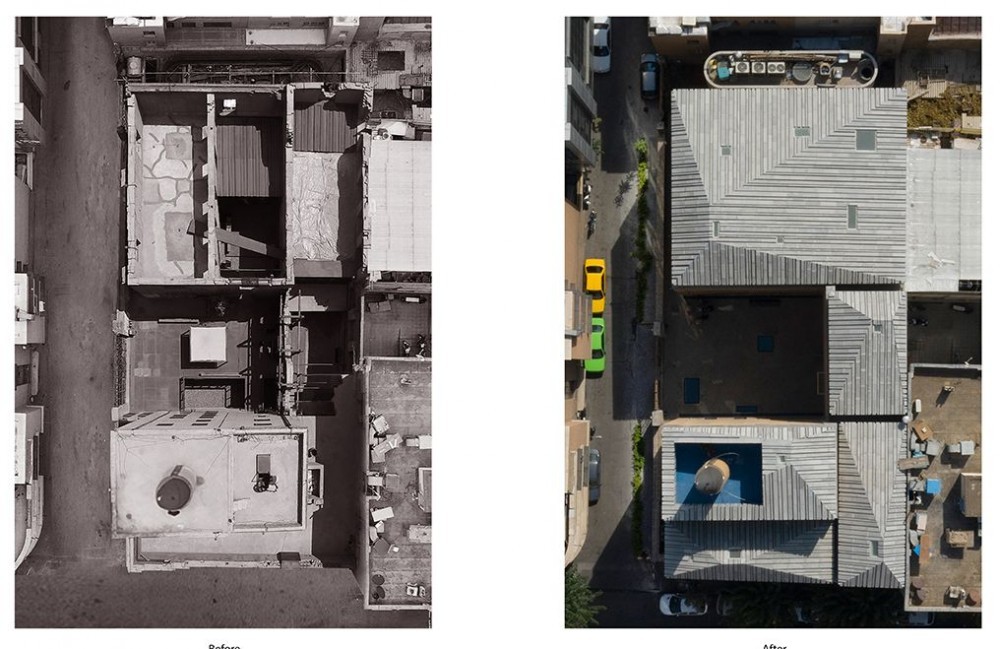

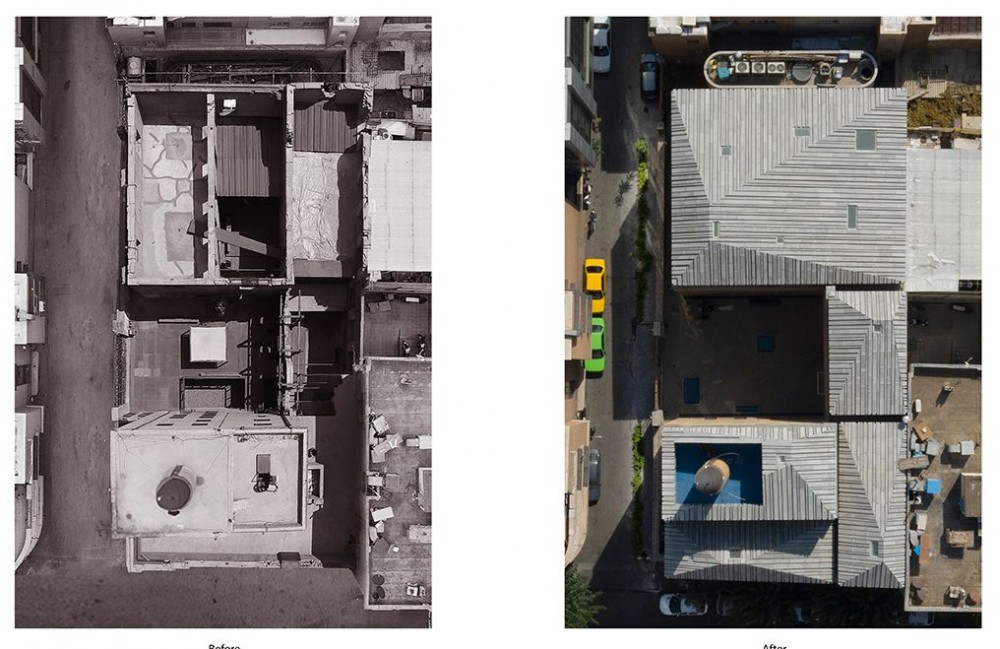

Before and after view of the roof of the Argo Museum in Tehran, Iran. Image courtesy of ASA North. Courtesy of ASA North.

-

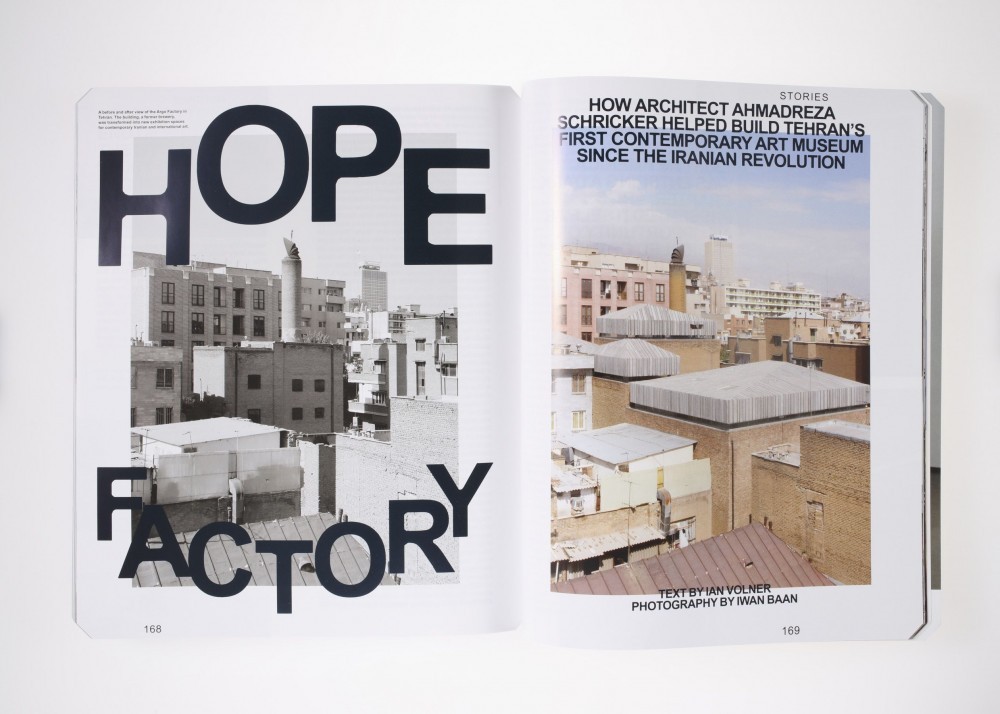

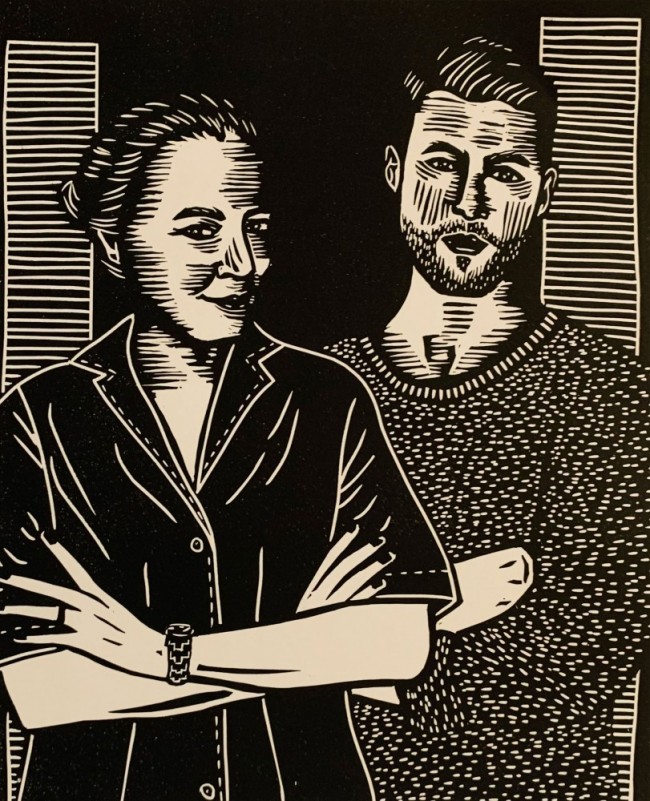

Page layout of the story in PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22, designed by Office Ben Ganz.

“Downtown Tehran is sort of like the Bronx,” says Schricker, and while some might take exception to the comparison (this author, as it happens, lives in the Bronx), it’s easy to see what he means: as the wealthy moved up and out, the area around Argo went into decline. Those who remained made do with what they could find, so the old brewery slowly fell prey to scavengers.

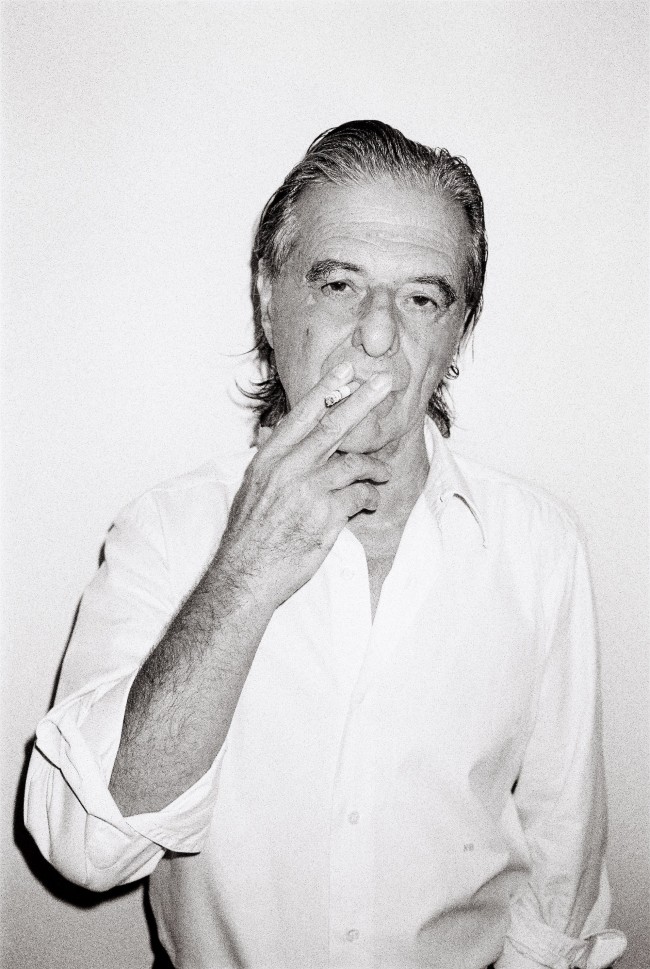

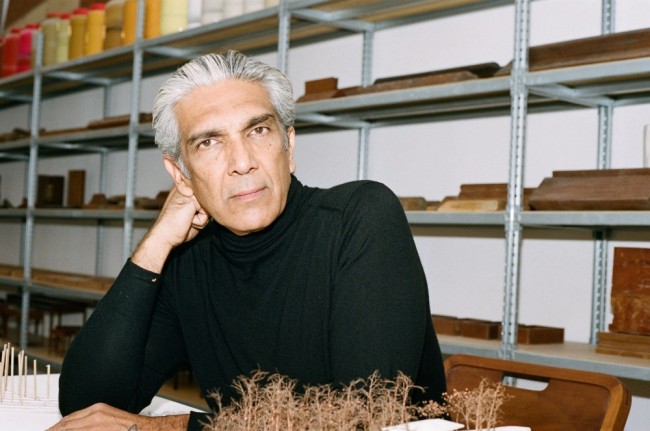

Until, that is, Schricker and a group of ambitious collaborators intervened. In January 2020, the former brewery reopened as a bold contemporary art museum, the Argo Factory, designed by York-based firm ASA North for Hamidreza Pejman, one of Iran’s most prominent contemporary art collectors, whose eponymous foundation helped finance the museum’s construction. The architect and the aficionado launched their collaboration in 2016, and from the very beginning they’ve shared a distinct vision for the kind of cultural space the building could become. “We didn’t just want a place that was cool,” says Schricker, whose work has been instrumental in establishing Argo as an exhibition space for a number of local and international artists. “Our goal was to create a world-class museum.” The project, adds Pejman, echoing that sentiment, was launched “with the thought of reviving the relationship between Iranian contemporary art and its international peers.”

Led by Ahmadreza Schricker and his firm ASA North, the Argo Factory project brought together a group of new-generation Iranian architects, including Mehdi Holakoui and Mona Jan-Ghorban. Behrang Bani-Adam, Patrick Hobgood Architects, Amin Mahdavi, and Oana Stănescu were part of Schricker’s international group of collaborators and advisors. Photography by Iwan Baan with Ahang Ahmadi and Keyvan Radan.

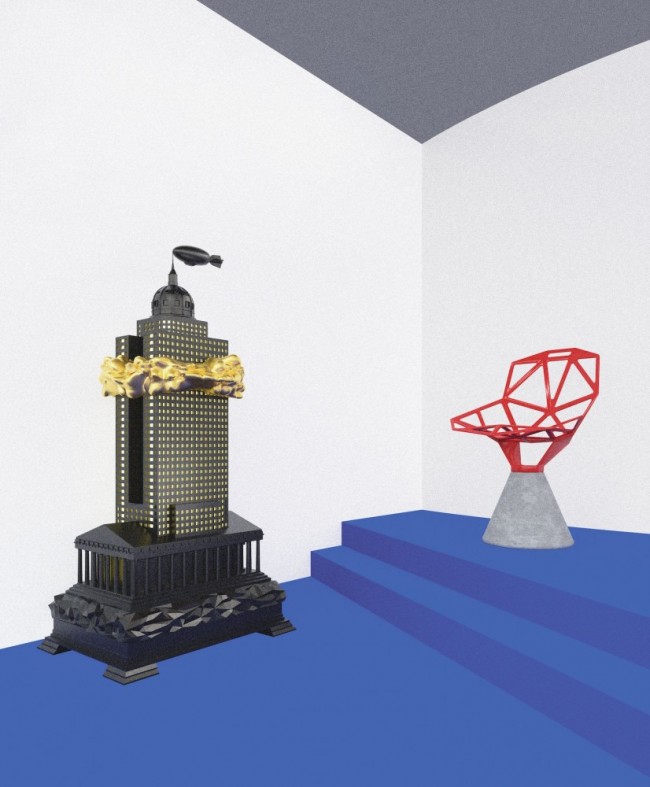

In pursuit of that objective, the Argo team had to overcome a litany of challenges. First and foremost the old building: roofless, essentially floorless, with missing patches all along its aging brick walls, the brewery hardly seemed a promising place for displaying contemporary painting and sculpture. A simple idea guided the architectural approach. “The roof would be the only newly built portion,” Schricker explains, while the remaining structure would be restored and refurbished, a move the architect terms “an act of respect.” The initial concept imagined a sequence of gabled crowns — “five hats,” as Schricker calls them — atop the factory, supported by new piers rising directly from the foundation, so that the roof would operate as a separate structure, wholly independent of the existing building. The “hats” themselves were to be polished brass, making for a gleaming, glamorous roofscape in sharp contrast to the rough brick façade below.

-

Before and after view of the Argo Museum in Tehran, Iran, seen from Taqavi Street. Image courtesy of ASA North.

-

The Argo Foundation’s roof was originally conceived out of brass. Due to trade shortages Schricker opted for precast concrete with a raked texture, whose formal language is echoing the corrugated metal roofs visible everywhere in Tehran. Photography by Iwan Baan with Ahang Ahmadi and Keyvan Radan.

And then came an unforeseen difficulty. “In 2016, you had the American election,” says Patrick Hobgood of Hobgood Architects, a North Carolina-based architecture firm that collaborated with Schricker in the concept phase. “Just as America was entering a dark chapter, Argo presented itself as an opportunity of unbridled optimism.” But MAGA politics in America, where Schricker himself was trained, and where he previously worked as a project architect for global firm OMA, brought with it a complete freeze in Iranian-U.S. relations, as well as a host of new trade sanctions that made brass prohibitively expensive. ASA North considered alternative materials — stone, wood — before settling on precast concrete with a raked texture that echoes the corrugated roofs prevalent in downtown Tehran. In a further nod to local building culture, the concrete hats are pierced with apertures at regular intervals, recalling the skylights in many Iranian buildings that help occupants keep track of the hours for daily prayer.

-

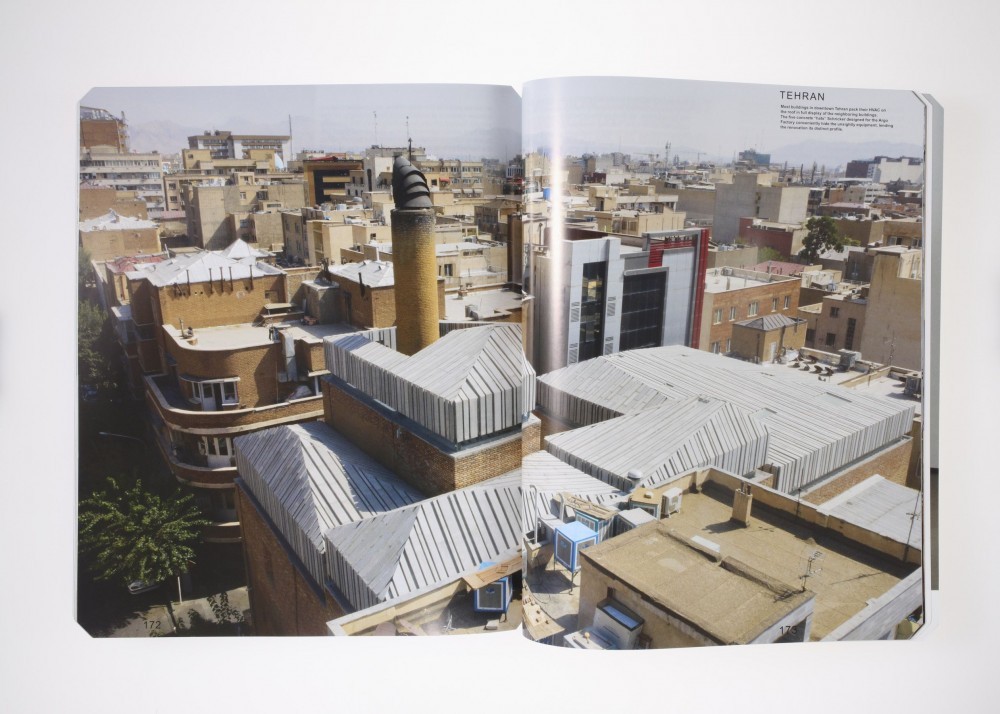

Page layout of the story in PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22. Full-bleed double page image by Iwan Baan with Ahang Ahmadi and Keyvan Radan.

-

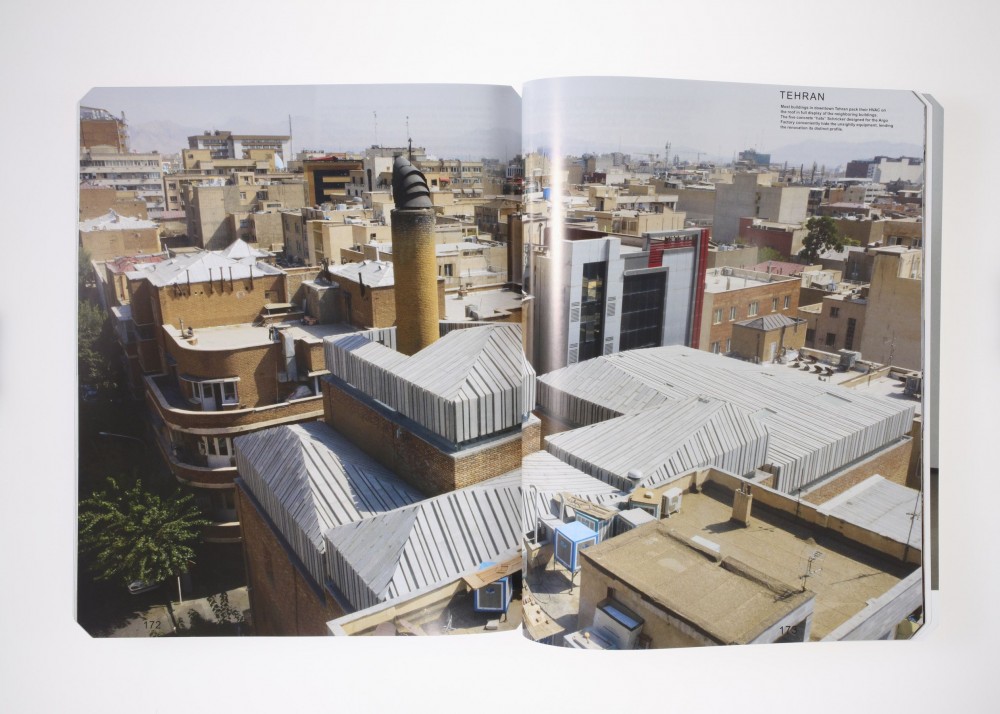

Most buildings in downtown Tehran pack their HVAC on

the roof in full display of the neighboring buildings.

The five concrete “hats” Schricker designed for the Argo Factory conveniently hide the unsightly equipment, lending the renovation its distinct profile. Photography by Iwan Baan with Ahang Ahmadi and Keyvan Radan.

Still more obstacles lay in store for Argo’s creators — not the least being a bureaucratic hiccup that nearly halted the building process, requiring the personal intervention of Tehran’s mayor. But at last the museum has opened, albeit with somewhat muted fanfare due to the Iranian capital’s ongoing coronavirus epidemic. The lucky few who have seen it say the museum lives up to Schricker and Pejman’s lofty ambitions: from the sinuous main stairway, which carries visitors from the ground floor to the upper-story galleries, to the vault-like basement level carved out of the former brewing vats, to the private events space with its striking view over the signature roofline, the building manifests a degree of finish and spatial sophistication that make it a contender on the international culture circuit. Surprises abound, and even the unassuming exterior is studded with subtle moments of design daring: when repairing the aging façade, Schricker replaced a few of the missing or damaged bricks with transparent glass blocks, so that at night tiny spikes of light emanate from the factory’s dark mass.

A dramatically curved marble staircase leads from the entrance lobby into the exhibition spaces on the Argo Contemporary Art Museum and Cultural Center’s upper floors. The project’s total square footage is 20,343. Photography by Iwan Baan with Ahang Ahmadi and Keyvan Radan.

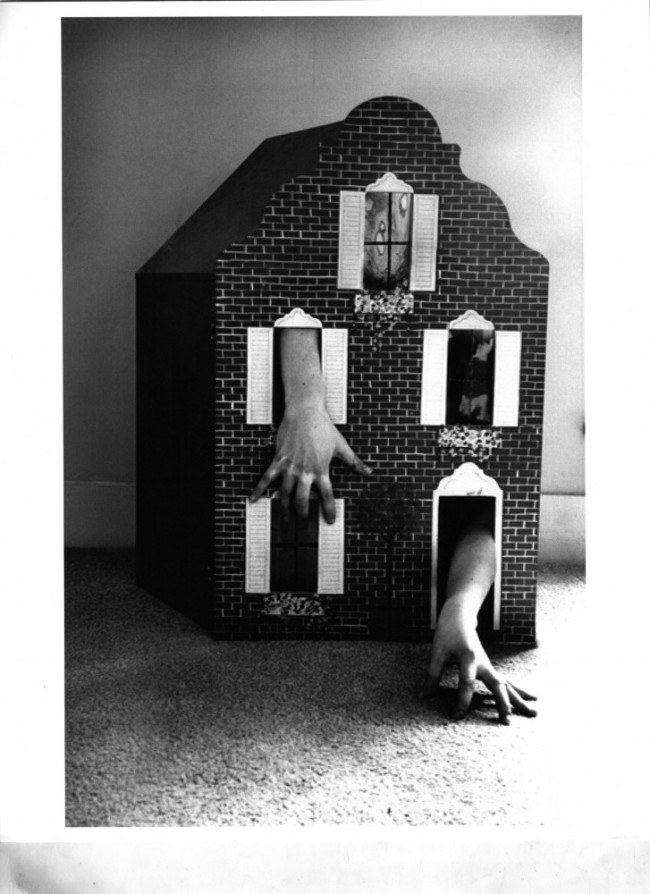

With a new administration in the White House and the prospect of a less dire pandemic on the horizon, Schricker is looking forward to a brighter day in Tehran that will bring with it the crowds the Argo Factory was made to welcome. Recent exhibitions have included those by Iranian artists Nazgol Ansarinia, Ali Meer Azimi, Mohammad Hassanzadeh, Neda Saeedi, and Newsha Tavakolian, as well as a video group show in collaboration with Paris’s Musée d’Art Moderne (featuring work by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Meriem Bennani, and Peter Fischli & David Weiss, among others). Next up is a show of unrealized projects by Iranian sculptor Mohsen Vaziri-Moghaddam.

-

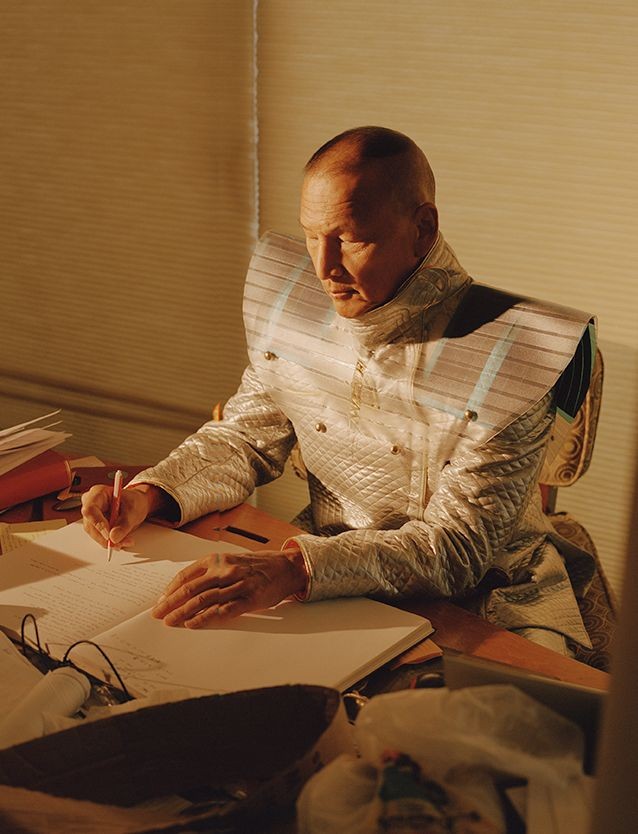

Concept image for the transformation of the Argo Factory into a contemporary art museum. Image by Ahmadreza Schricker/ASA North.

-

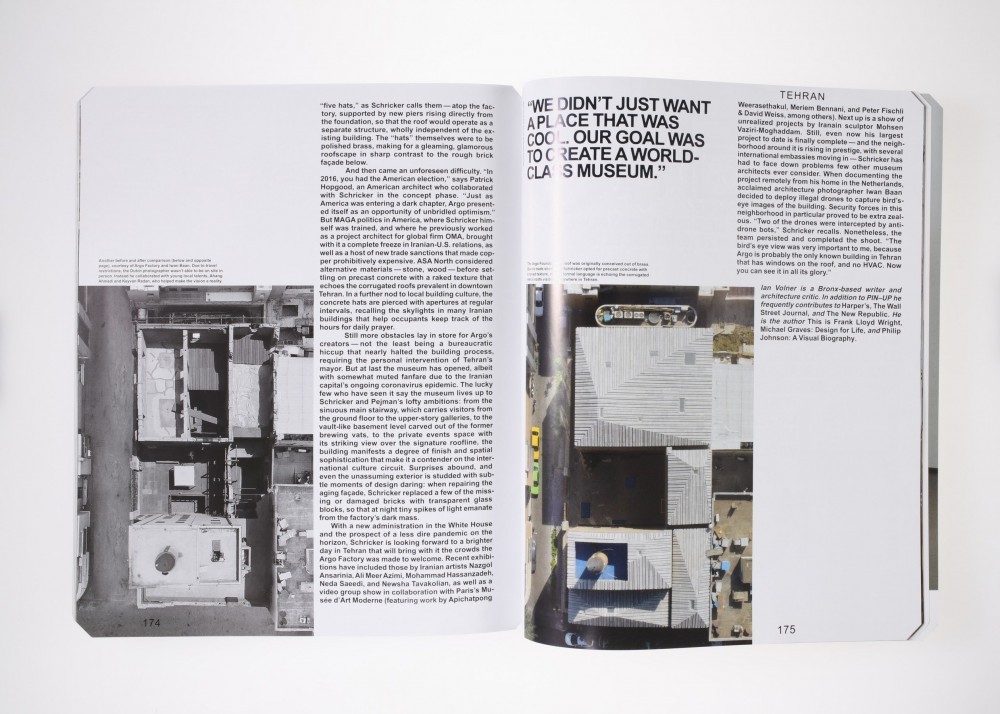

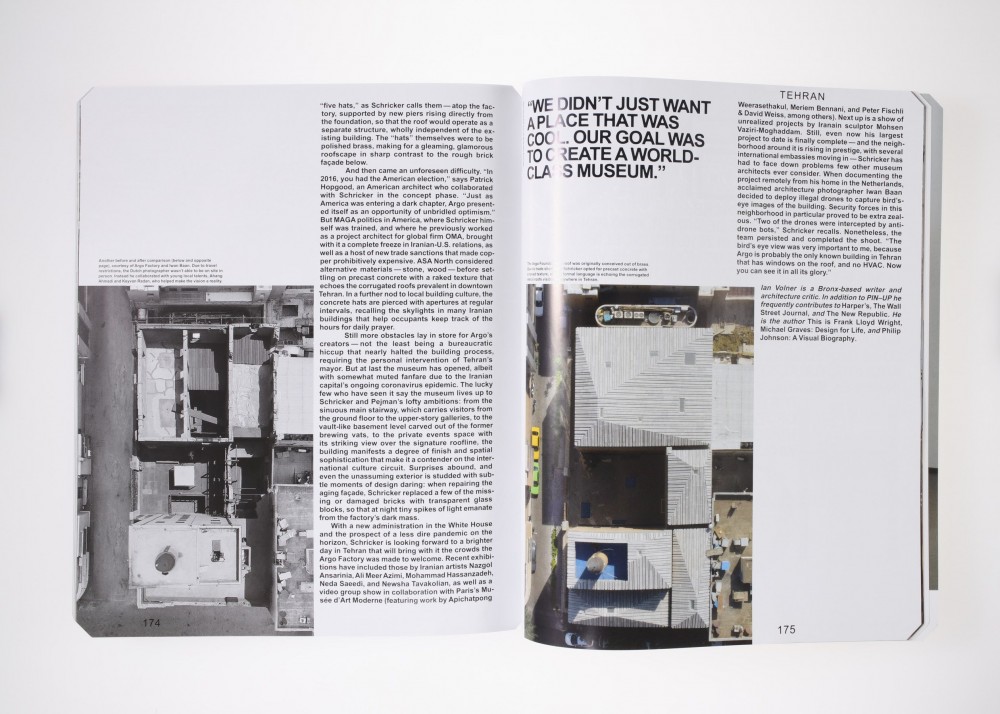

Page layout of the story in PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22, designed by Office Ben Ganz.

-

Before and after aerial view of the Argo Museum in Tehran. Images courtesy of ASA North (left) and Iwan Baan (right) with Ahang Ahmadi and Keyvan Radan.

Still, even now his largest project to date is finally complete — and the neighborhood around it is rising in prestige, with several international embassies moving in — Schricker has had to face down problems few other museum architects ever consider. When documenting the project remotely from his home in the Netherlands, acclaimed architecture photographer Iwan Baan decided to deploy illegal drones to capture bird’s-eye images of the building. Security forces in this neighborhood in particular proved to be extra zealous. “Two of the drones were intercepted by antidrone bots,” Schricker recalls. Nonetheless, the team persisted and completed the shoot. “The bird’s eye view was very important to me, because Argo is probably the only known building in Tehran that has windows on the roof, and no HVAC. Now you can see it in all its glory.”

Text by Ian Volner, a Bronx-based writer and architecture critic. In addition to PIN–UP Volner frequently contributes to Harper’s, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic. He is the author This is Frank Lloyd Wright, Michael Graves: Design for Life, and Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography.

All photography courtesy of Iwan Baan and ASA North.

Project Details

Ahmadreza Schricker (ASA North – lead architect), Mehdi Holakoi (ASA North – job captain), Mona Jan-Ghorban (ASA North – project manager), Amin Mahdavi (ASA North – special advisor), Behrang Bani-Adam (ASA North structure), Patrick Hobgood (Hobgood Architects – collaborating architect), Cam Fuller, David Ji, Chris Lacy, Alan Tin, Robert Macia (structure), Vandad Developments (developer), and Oana Stănescu (design advisor).

Special thanks to Shahdeh Ammadi