CRACK UP — CRACK DOWN: Ljubljana Biennial Curated By Slavs And Tatars

When Payam Sharifi flies, he gets around the no-liquid airport security policy by bringing a lemon in lieu of dressing to garnish his home-cooked meal. For the Slavs and Tatars co-founder, circumventing the bureaucratic restriction makes the lemon juice he squeezes on his meal all the more delicious, the sour contrasted and complemented by the sweetness of its surreptitious delivery. Sharifi and co-founder Kasia Korczak used the same symbiotic relationship as a framing device for the 33rd Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts, which they curated together as Slavs and Tatars this past June. They open their curatorial statement for the biennial, titled Crack Up — Crack Down, with the idea that “we live in sour times, and such sour times require sweet-and-sour methods.”

The Slovenian biennial was a new frontier of sorts for Slavs and Tatars, built on the practice Sharifi and Korczak have been developing since forming the collective in 2006. They describe themselves as “a faction of polemics and intimacies devoted to an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia,” and over the years, working between Berlin, Moscow, Brussels, and Paris, their provocations have taken shape in myriad ways from lecture-performances and research-based publications to sculptures and installations. For this, their first time ever curating a biennial, Slavs and Tatars’s approach is refreshing, eschewing the played-out curatorial style one comes to expect on the biennial circuit. The sum of their choices takes on a more acrid flavor than usual, while the featured works spotlight meditations on latent histories and projected futures. For example, Lin May Saeed’s Reiniger (2006), an eerie figurative sculpture with a plastic watering can for its head, references clean-up attempts after the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, while author and activist Hamja Ahsan’s referendum asks citizens whether or not they would prefer to join Aspergistan, an imagined republic for the neuroatypical and introverted, the work functioning as a sardonic commentary on democracy in our age of fracturing realities.

Lin May Saeed's Reiniger (2006) at the 33rd Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts. Image courtesy Jaka Babnik.

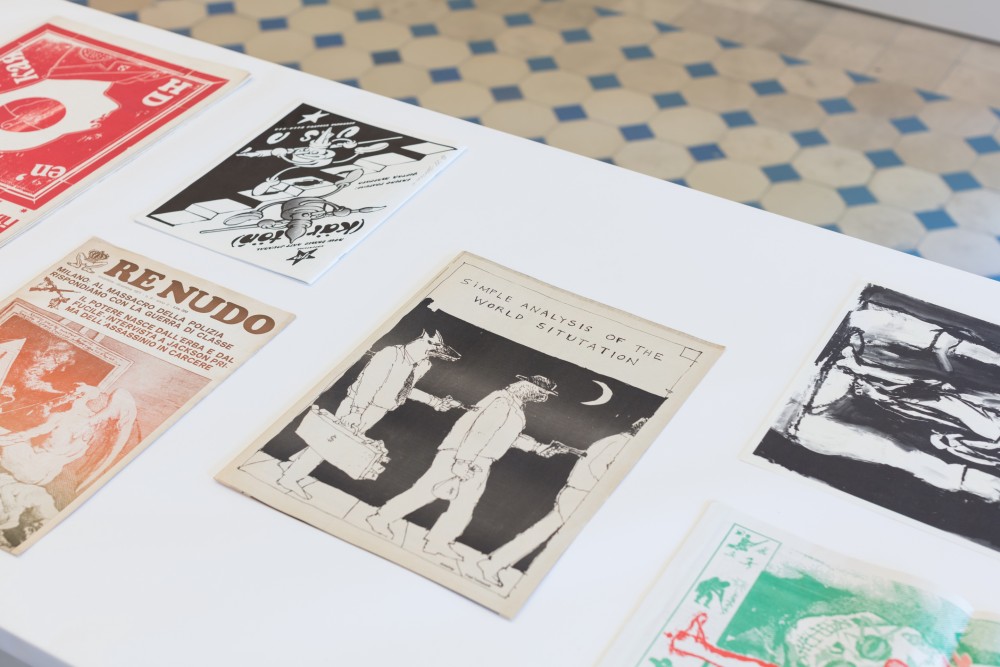

Satire is a loose theme organizing the selections, underscoring the political and pleasurable potential of humor simultaneously to disguise and reveal bitter truths. No More Fuchs Left to Give, a polemical reading-room installation by rare-books dealer Arthur Fournier and comparative-literature scholar Raphael Koenig, presents lithographs and satirical cartoons by German book collector, art historian, and Marxist activist Eduard Fuchs (1870–1940), the meme-equivalents of the late-19th and early-20th centuries. Archival prints of these politically-charged comics are displayed alongside contemporary copies cheaply printed on canvas bought from walmart.com, their frugality evoking dorm-room decorations. The contrast between the copy and the original forces the viewer to confront how the medium influences the message’s power, as well as the proliferation of political imagery in the age of infinite reproducibility — a provocation that may offer us clues for dealing with present-day meme-ified culture.

-

No More Fuchs Left To Give at the 33rd Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts. Image courtesy Jaka Babnik.

-

No More Fuchs Left To Give at the 33rd Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts. Image courtesy Jaka Babnik.

-

No More Fuchs Left To Give at the 33rd Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts. Image courtesy Jaka Babnik.

The works and artists included in the biennial span generations, centuries, and cultures, resulting in surprising and sometimes haunting juxtapositions. The precocious millennial Nigerian-American designer and artist Dozie Kanu’s badass Bench on 84’s (2017) is joined by more recent work commissioned for the biennial. With his slightly-taller-than-standard film director’s seat, Chair (xiii) (Stand Up)(Ja Rule) (2019), Kanu uses scale to comment on power dynamics in the creative industries, the piece accompanied by handcuffs and two smaller foot stools, respectively Scrool (Ur Boy Bangs) and Scrool (Supahead) (both 2019), their canvas seats printed with illustrations of black figures, stereotypes of performers from the 19th century to today. In a move of curatorial heft, these furniture pieces are surrounded by L.A.-based artist Amanda Ross-Ho’s Hurts Worst series (2018–19), large sequined wall works depicting cartoonish faces in agony culled from the widely used medical-symbol system for communicating pain levels, their emoji-like simplicity at once belying and evoking the complexities of collective contemporary distress, the specifics of which Kanu teases out. The combined effect is somehow cathartic, hopeful even — once again a mix of sour and sweet.

-

Amanda Ross-Ho’s Hurts Worst series (2018–19) and chair by Dozie Kanu at the 33rd Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts. Image courtesy Jaka Babnik.

-

Amanda Ross-Ho’s Hurts Worst series (2018–19) and Dozie Kanu's Bench on 84's (2017) at the 33rd Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts. Image courtesy Jaka Babnik.