SO RATTAN: New Ways of Having Fun with One of Humanity’s Oldest Materials

A baby floating down the Nile in a wicker basket… So begins the biblical story of Moses and one of the earliest mentions of the rattan in functional form. In the 34 centuries since wicker and rattan remained a constant in the world of design, used in everything from baskets to chairs to buildings. Its relevance has shifted through time, peaking in the colonial context of the 19th century (when wicker took forms both monstrous and whimsical), and again in the 20th century, in the work of designers like Jean-Michel Frank and Charlotte Perriand in France, Franco Albini and Gabriella Crespi in Italy, and Paul McCobb and Paul Frankl in the U.S.

A Heywood-Wakefield Company truck in Wakefield, Massachusetts, the “rattan capital” of the United States (c. 1917). Courtesy of the Wakefield Historical Society.

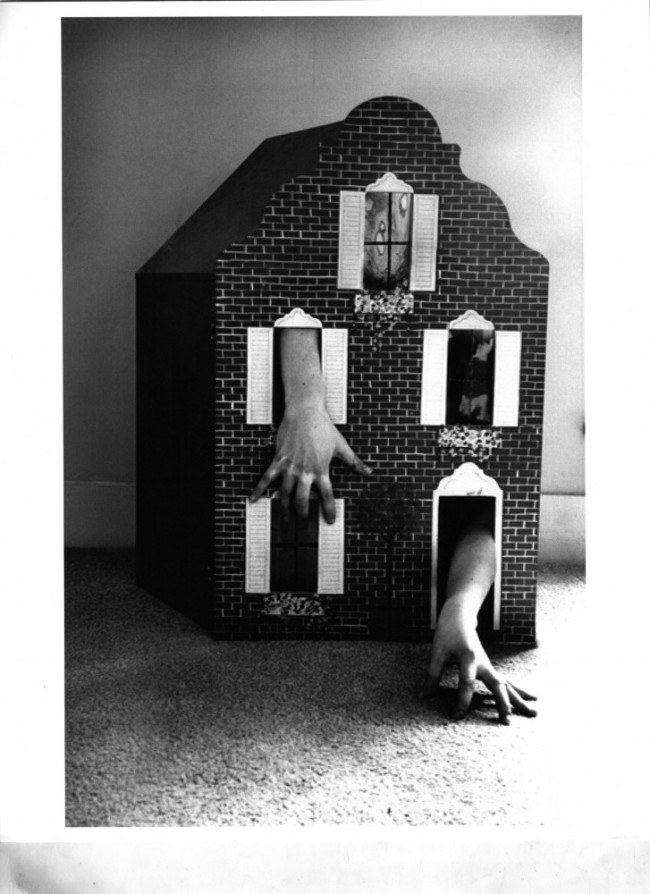

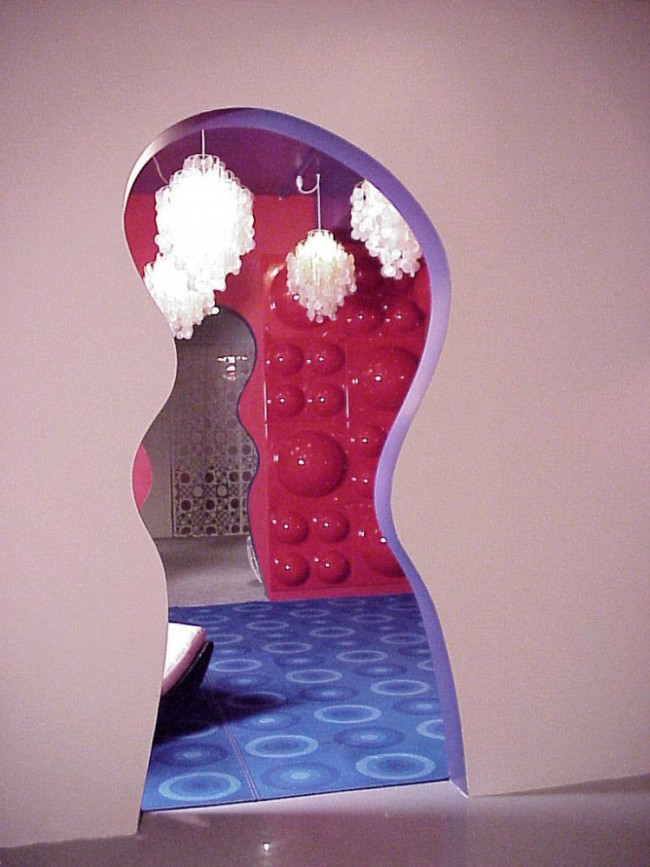

Today, wicker and rattan are having a moment again, in both furniture and interiors. Artists like Katie Stout and Chris Wolston are proposing new designs, while interior designers like Adam Charlap Hyman of architecture firm Charlap Hyman & Herrero incorporate vintage examples alongside with the new. “It brings a historical note into a room, in addition to warmth and a sense of craft,” says Stout, whose contemporary wicker and rattan lexicon includes sideboards, vanities, and shelves. “We try to use rattan or wicker in every project we do,” adds Charlap Hyman. “There’s something so graceful about it.” Humor lives alongside the grace, as Wolston can attest with his own anthropomorphic wicker pieces complete with arms, legs, and comically bulging butt cheeks.

-

Chris Wolston, Super Model chair, 2021; woven Colombian mimbre (wicker). Courtesy of The Future Perfect.

-

Chris Wolston, Body mirror, 2021; mirrored glass, woven Colombian mimbre (wicker). Courtesy of The Future Perfect.

For Stout the material is nostalgic. “My mom taught me how to weave baskets,” she remembers. “So weaving was always a way to connect with her.” Wolston also has early memories of weaving, but finds, in addition, that it offers an opportunity to connect more deeply with the local community in Medellín in Colombia, where he lives and works. “Wicker is very present there,” he says. “Working with it necessitated finding weavers, and we found one whose ethics we liked — he has a profit-sharing cooperative.” The increasingly figurative nature of Wolston’s Nalgona chairs, made from 100-percent ethically sourced mimbre (Spanish for wicker), engendered very particular challenges. “Weaving the wicker onto our frames is very much like applying a skin. We create the skeletons and the weavers apply the flesh. It was interesting because we were defining how to weave an ass!” (The latest pieces can currently be seen at Casa Perfect in Los Angeles.)

-

Chris Wolston, Paramo cabinet, 2021; woven Colombian mimbre (wicker). Courtesy of The Future Perfect.

-

Chris Wolston, Paramo cabinet, 2021; woven Colombian mimbre (wicker). Courtesy of The Future Perfect.

-

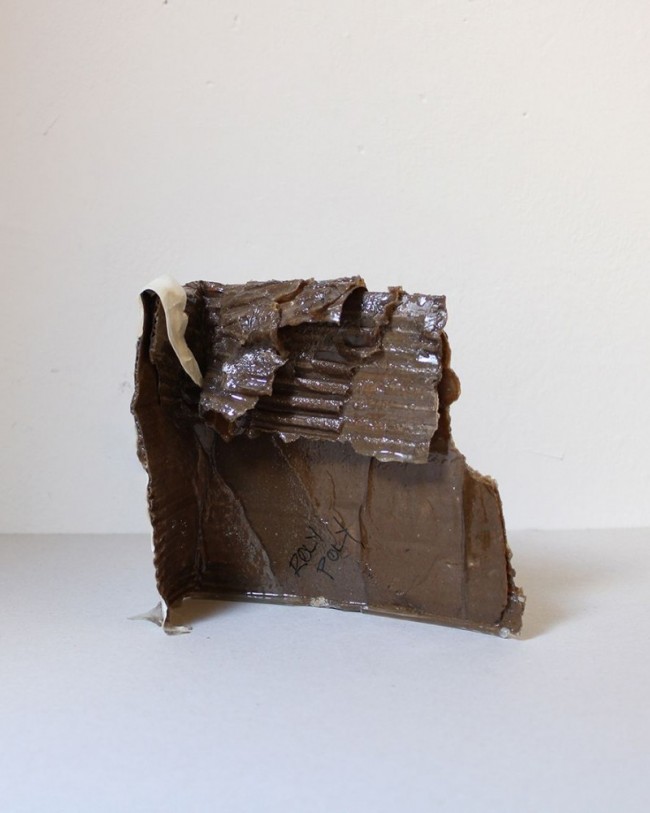

Katie Stout, Rock Wicker cabinet, 2020; Wicker, river rocks, wood. Courtesy of Nina Johnson Gallery.

-

Katie Stout, Rock Wicker cabinet (detail), 2020; Wicker, river rocks, wood. Courtesy of Nina Johnson Gallery.

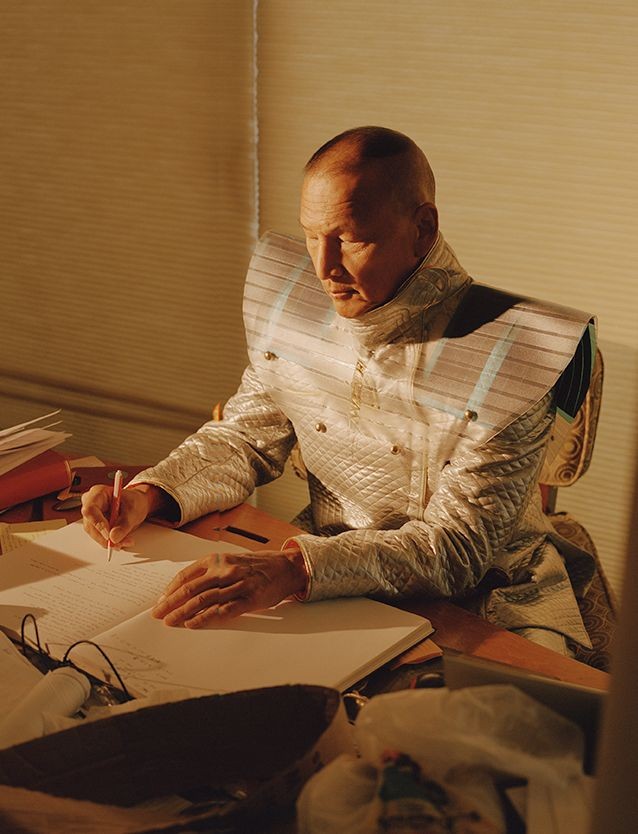

This is far from the first time woven plant material has been used as “skin,” though, for rattan can be also be made into clothing, from the traditional girdles worn by Wemale women on Seram Island in Indonesia, to Rattan Body, the 1981 collection designed by Issey Miyake using rattan and bamboo ribcages and constructions (and which landed on the 1982 cover of Artforum). Though rattan is frequently thought of in the West as a “humble” material, it has served as anything but in non-Western cultures. Benin City, one of the most powerful and ancient settlements in pre-colonial Western Africa, featured palm-roofed buildings before the English raised the city to the ground in 1897. And The Met alone holds several examples, such as an elaborate 18th-century Chinese armchair with a bamboo frame, rattan seat, and ivory inlay, and its much earlier predecessor, a 13th- or 14th-century carved and lacquered Ming Dynasty folding chair with a rattan seat, indicating rattan and wicker’s presence in aristocratic spaces. Even in a contemporary context, suggests Charlap Hyman, rattan and wicker’s modest reputation should be questioned. “I don’t think of it as something humble. In reality the good stuff is expensive.”

-

Charlap Hyman & Herrero, Alexandra chair (detail), 2020; rattan, steel. Courtesy of The Future Perfect.

-

Charlap Hyman & Herrero, Leora chair, 2020; rattan, steel. Courtesy of The Future Perfect.

-

Charlap Hyman & Herrero, Alexandra chair (left) and Leora chair (right), 2020; rattan, steel. Courtesy of The Future Perfect.

Rattan and wicker also hold a special place in the cultural imagination because of their relationship to portraiture. In the late-19th century, elaborate wicker furniture became a favorite photographer’s prop, adding decorative gravitas to any shot, regardless of the sitter’s wealth or social status. The early 20th century saw the rise of the peacock chair, with its sloping back and throne-like form. One of the earliest known photographs of it was taken in 1914 in Bilibid Prison in the Philippines, where inmates manufactured rattan and bamboo furniture. As the century progressed, everyone who was anyone posed in it at one point or another, from U.S. presidents to Hollywood actresses. In 1968, Blair Stapp photographed Black Panther Party leader Huey P. Newton in a peacock chair, with a spear in one hand and a gun in another. The image was widely distributed in Black households, and the chair was even displayed at rallies as a proxy for Newton when he couldn’t attend, cementing it as a symbol of Black liberation.

Michelle Obama’s prom photo from 1982. Courtesy of Michelle Obama Instagram.

Today’s rattan-friendly designers are more drawn to wicker’s psychic warmth. “It’s such a compelling material, because you can see the hand in it,” argues Charlap Hyman. “A natural material like grass, rattan, or reed is transformed into something ornate and structural.” Its current popularity is likely a reaction to the toxic plastics and resins that have dominated the design world in recent years. “People are concerned with off-gassing and unstable materials that get funky over time,” says Stout. “I think that’s why they’re really connecting to natural materials like rattan.” In an era of overconsumption, radical climate change, and dwindling resources, renewable rattan and wicker root us to the Earth and other humans, providing a soft place to land. Or a safe vessel to bring us home.

Text by Camille Okhio

Chris Wolston’s exhibition Temperature’s Rising is on view at Casa Perfect in Los Angeles until December 2021.