OBJECT MANOR: CHARLAP HYMAN & HERRERO’S TRIBUTE TO MARIO PRAZ

Tell a Roman you’re on your way to Casa Mario Praz, a stone’s throw away from the River Tevere, and you might encounter a startled expression. During his lifetime, it was widely believed that Praz, a critic and scholar whose works include An Illustrated History of Interior Decoration, possessed the evil eye, and the art- and antique-filled residence on the third floor of Palazzo Primoli where he lived for three decades until his death in 1982, still has an unlucky reputation among locals. The residence — now a museum — is best illustrated in Praz’s spatial autobiography, The House of Life (1958), which delivers a cinematic room-by-room account of the home and its contents. The text draws a portrait of Praz through the objects he chose to possess and the way he exhibited them. Paying homage to Praz and his storied home, architecture and design firm Charlap Hyman & Herrero curated at Tina Kim Gallery the group show For Mario, a mix of contemporary and modern art and design objects complemented by unconventional exhibition design, floor-to-ceiling cotton muslin drapes that evoke a tension between preservation and transience.

-

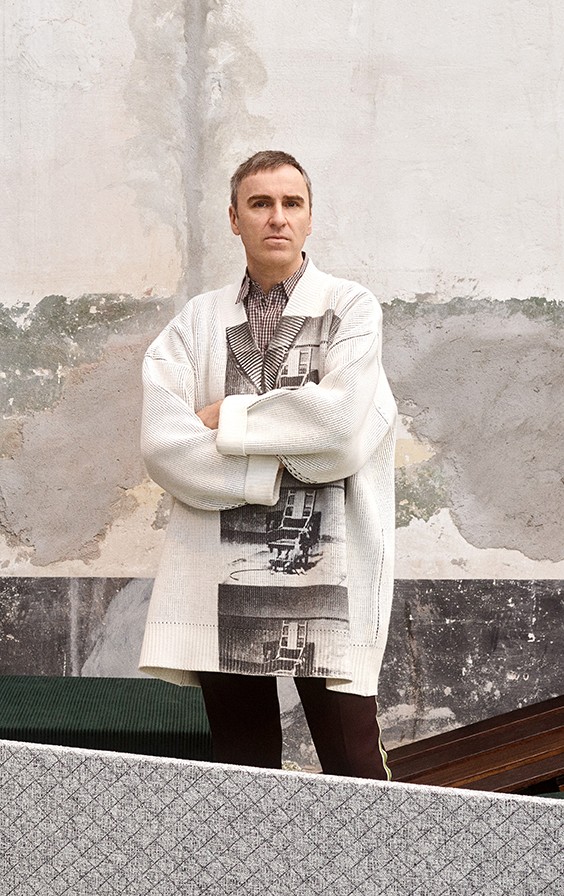

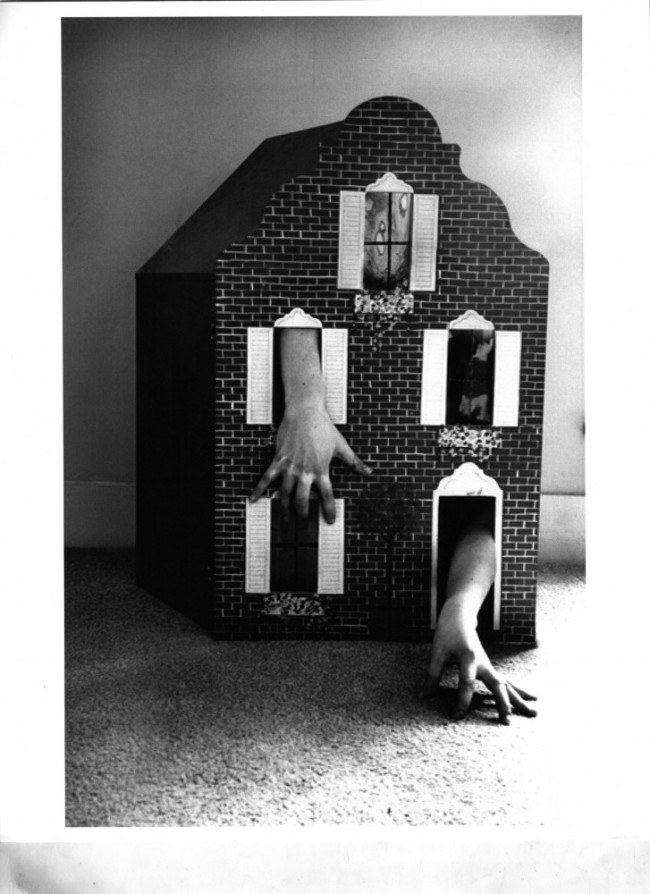

Installation view of For Mario, 2019. Image by Jeremy Haik.

-

Installation view of For Mario, 2019. Image by Jeremy Haik.

-

Installation view of For Mario, 2019. Image by Jeremy Haik.

The curtains, in addition to a triangular bed (courtesy of June 14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff) in the exhibition’s first room also draped in the same cream-colored cotton muslin as the walls, lend the gallery the feeling of a domestic space, transforming the viewer’s gaze into a voyeuristic one, making one feel as if they’re meandering through the collection of a bygone host whether Praz or someone else. The objects in this collection include Louise Bourgeois’s fabric sculpture Couple (2001), two bodies formed in a gentle caress; Thomas Barger’s hefty and whimsical chair for two, Love Me, Protect Me Chair (2018); and Davide Balliano’s ceramic sculpture, UNTITLED_CG_L (2014), an ambiguous hollow form like one half of a vase — all three in varying shades of a robin’s egg blue. There’s a sense of playfulness in many of the works and how they’re displayed. Girl in a Red Landscape (2014), Ghada Amer’s colorful portrait of a woman on ceramic, is hung in front of the drapery in a way that the figure seems like she’s gently sneaking her head out for a peek. Oren Pinhassi’s adjacent work, a plant-like sculpture with leaves pierced with hanging toothbrushes, injects a sense of humor into the exhibition while maintaining the domestic theme. At the same time, Pierre Jeanneret’s steel manhole cover, Manhole (ca. 1951–54), which the Swiss architect designed for the Indian city of Chandigarh, sits on the gallery floor near the bed, a sudden interruption to the domesticity that adds to the show’s surreality. Carlo Mollino’s Polaroid of a female nude — one of the architect’s posthumously discovered photos — evokes a sense of intimacy and mystery while the decision to leave Johannis (2007), an Anselm Kiefer painting of a hazy fall scene, sitting on the floor unhung, leaning against the wall, urges a feeling of abandonment, the type of melancholy that permeates into homes with furniture moved in preparation for departure, or arrival.

-

Installation view of For Mario, 2019. Image by Jeremy Haik.

-

Installation view of For Mario, 2019. Image by Jeremy Haik.

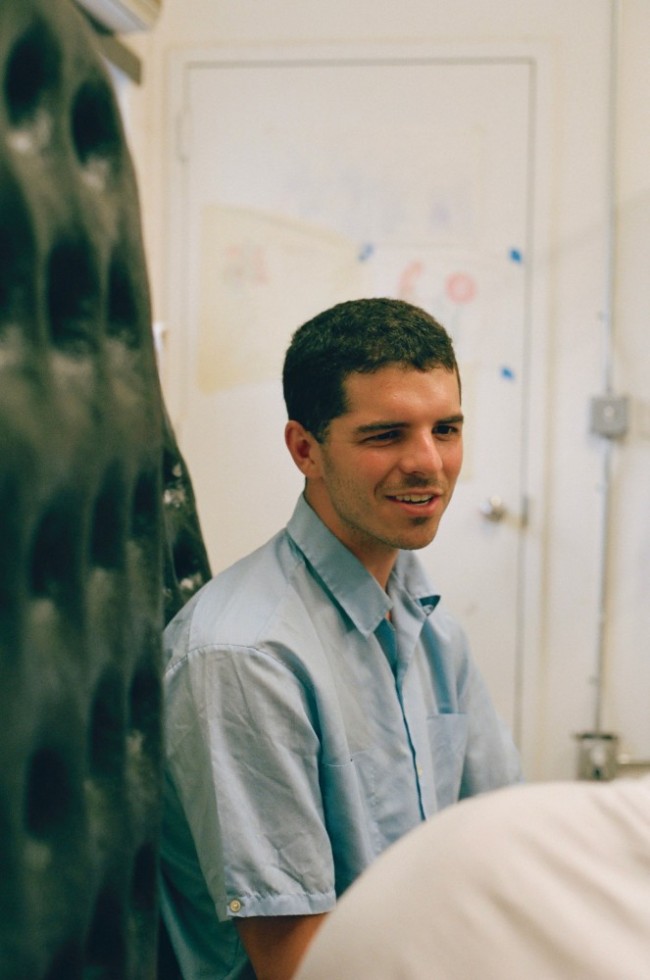

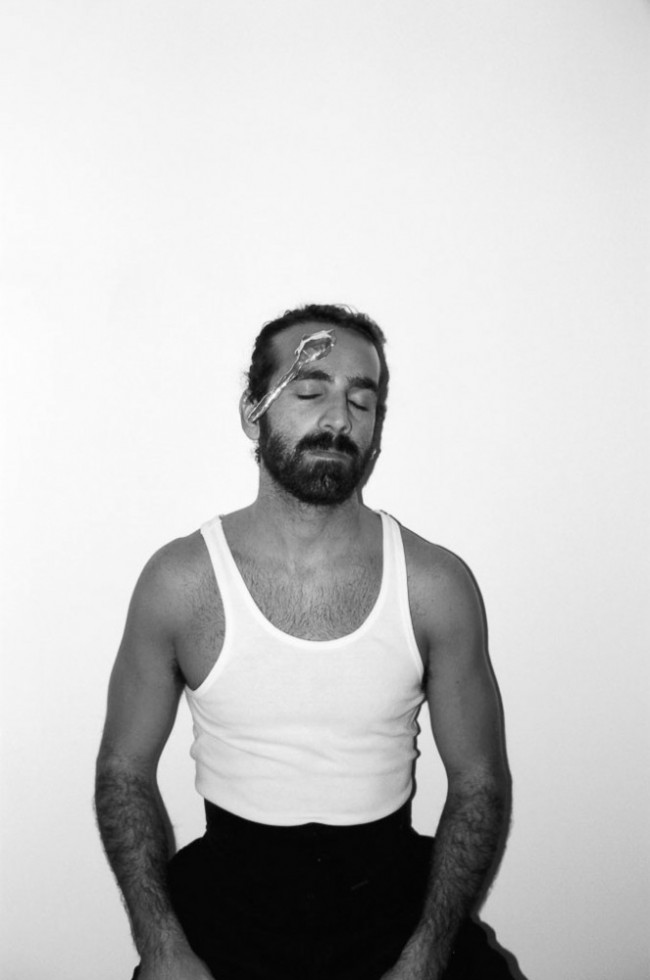

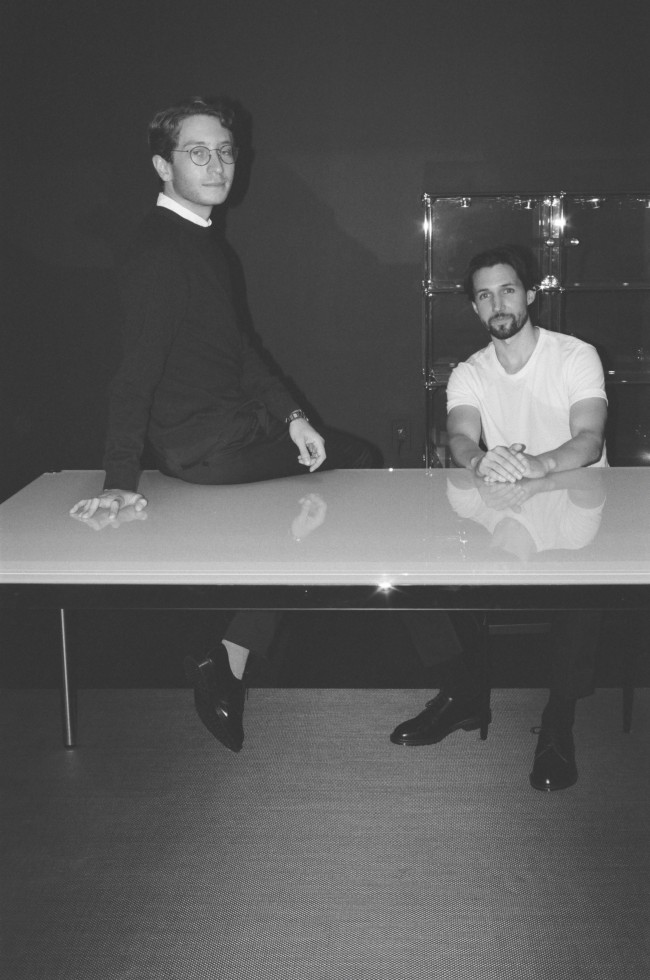

In fact, homes detaching from their objects have long attracted the show’s curators Andre Herrero and Adam Charlap Hyman, whose participation in the 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial consisted of three miniature models of the grand salon at Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé’s rue de Babylone apartment in Paris. The maquettes chronicled the abrupt emptying of the home as Bergé, no longer desiring to live with their collection following Laurent’s passing, auctioned off each piece. The duo’s models underscored ideas of attachment and impermanence that are echoed in For Mario. “There is melancholy in someone’s biography becoming dispersed,” says Charlap Hyman, “but materials outlive us. They go onto lead different lives in others’ houses, carrying traces from their former owners’ biographies.”

Text by Osman Can Yerebakan.

Photography by Jeremy Haik.