Interview with Jay Ezra, Co-Founder of ANNEX Gallery in Los Angeles

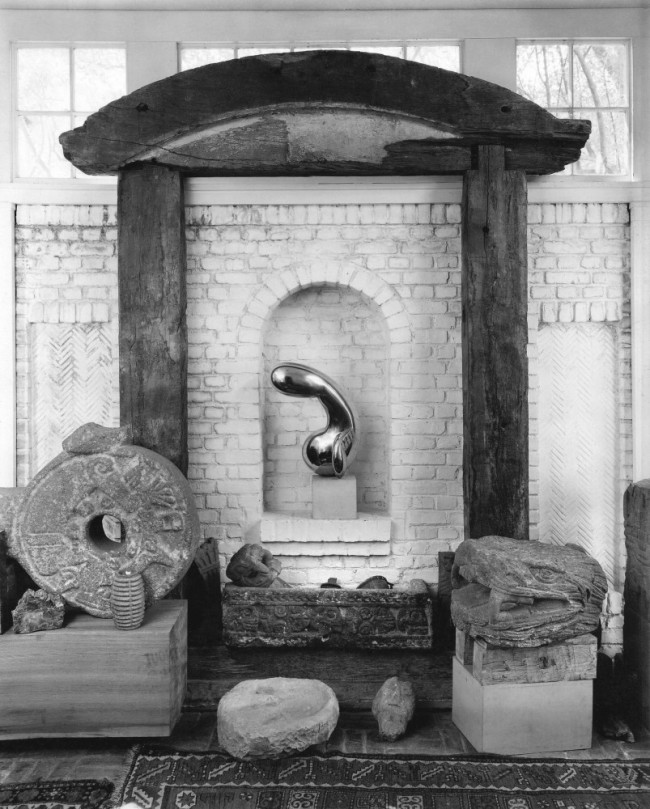

ANNEX co-founder and curator Jay Ezra Nayssan photographed by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP. Stool by Greg Ito, silverware by Oren Pinhassi.

Founded in early 2018, ANNEX is a “project-store” located in the former offices of M+B Gallery in West Hollywood. A joint venture between curator Jay Ezra Nayssan (of Del Vaz Projects) and art dealer Benjamin Trigano, the 750-squarefoot space is dedicated to showcasing artist-made design objects, “post-functionalist” artifacts that blissfully toss out the prescriptive mandate of design proper. Carefully assembled by Nayssan, ANNEX’s list of artists ranges from historic figures (Salvador Dalí, Picasso) to living icons (Charles Hollis Jones, Pedro Friedberg, Lucas Samaras), to contemporary newcomers like Bailey Scieszka and Max Hooper Schneider — they all share the stage together in what Nayssan dubs a “craftsman bungalow.” As ANNEX is gearing up for its Fall display as well as for a forthcoming solo show by New York-based Misha Kahn at the end of the year, PIN–UP caught up with the curator to discuss dinnerware, Fellini, and his love of the non-linear.

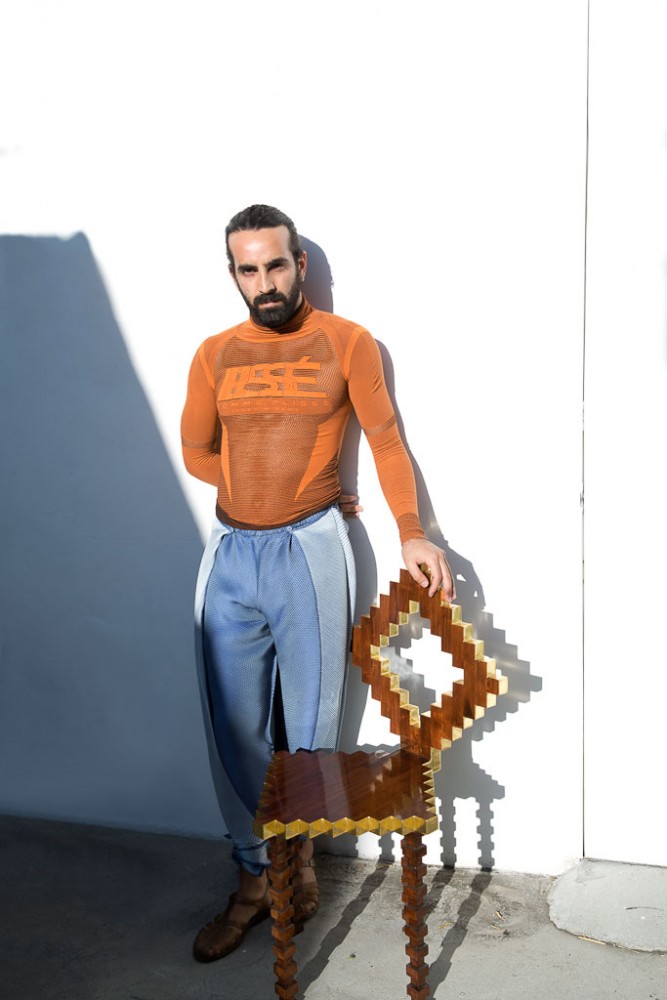

Jay Ezra Nayssan photographedy by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP. Chair by Pedro Friedeberg.

Back in 2014 you began a space out of your apartment, Del Vaz Projects. What’s it like running a show out of your apartment and using your own domestic, intimate space as a public exhibition?

My parents are both Iranian and there’s a cultural tradition of hosting and welcoming people into the home — it’s called paziraei. Del Vaz Projects is like a performance of this cultural practice that I’ve inherited. When I have visitors to an exhibition, it’s about preparing the tea and the dates and having somewhere to sit, having a conversation, and not necessarily going straight into the exhibition — just getting to understand people, what their interests are. On the side of hosting artists, that’s something that’s obviously a lot more involved because the artists usually come here for two to three weeks. They often make the work here in my home. I cook for them, I take them out. Sometimes we do an excursion to somewhere outside of Los Angeles. I introduce them to my friends and my family.

The artists stay with you?

Yes. I have two guest bedrooms, so if the artists are not from Los Angeles, they stay in one of the bedrooms, and they produce the work in the other bedroom — or in my garage — and then we install the show in the two bedrooms.

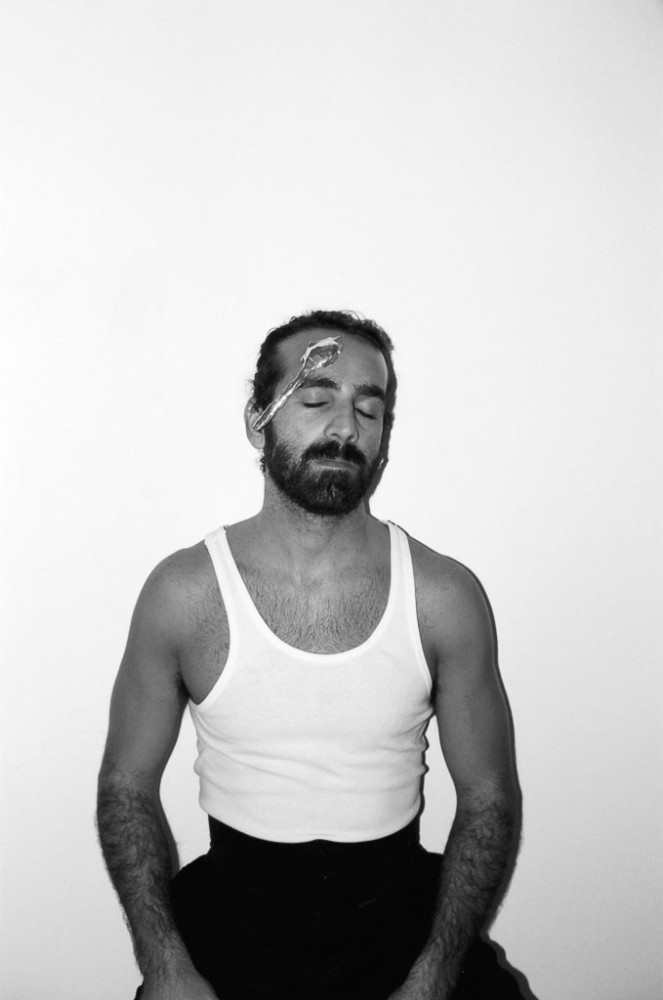

Jay Ezra Nayssan photographedy by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP. Silverware by Oren Pinhassi.

Do artists ever leave any of their work behind?

Yes. A lot of things from shows are left over here, or given to me as trade from the artists. I keep a lot of it in my living room and in my bedroom, where all the previous shows are starting to stack on top of each other.

-

ANNEX Winter 2018 installation: Greg Ito candlestick stool on Sophie Stone carpet. Photography by Ed Mumford. Courtesy of M+B Los Angeles.

-

ANNEX Winter 2018 installation: Painted room divider by Alina Perkins; Parrot cordless floor lamp by Grau01; illustrations by Pedro Friedeberg; carpets by Sophie Stone, Capitello chair by Studio 65. Photography by Ed Mumford. Courtesy of M+B Los Angeles.

-

ANNEX winter 2018 installation, from left to right: Floor lamp by Nicolas L.; tattooed toilet by Art of the Unknown; sand mirror by Alison Veit; wall lamp by Tiziana La Melia; tiled stool by Lisa Jo; ceramic vase by Ben Wolf Noam; porcelain bead curtain by Brittany Mojo . Photography by Ed Mumford. Courtesy of M+B Los Angeles.

How and why did you start working with Benjamin on ANNEX? And how is ANNEX different from what you are trying to do with your solo project, Del Vaz.

Benjamin and I kept in touch after Synesthesia, which was the exhibition that Daniele Balice and I did together at M+B gallery back in 2012. Over time our friendship became something that was based on a lot of shared interest and also disinterests. We realized we had the same tastes and distastes and at some point, he said, “You should come back and do a show.” And I thought that if I’m going to come back a do a show, it’s so much work for only six weeks in a gallery. I give myself three months anyway in my apartment. And if we’re going to do something together, I would love for it to be something kind of monumental, and for it to champion a cause, or establish a new community, or a new feel, or something like that. So Benjamin said, “All right, here’s the front house at the gallery, why don’t you take over for a year and we’ll see where it goes.” Eventually, that invitation for an exhibition evolved into this showroom space that really champions the ideas of in-betweenness and what Benjamin and I call “post-functionalist objects.” At ANNEX, we’re dealing mainly with visual artists, because that’s the community that Benjamin and I have been building over the years. We invite them to make design objects, in order to re-bridge these two often-separated realms of art and design. For artists, the function of an object isn’t really premeditated upon, it isn’t the primary goal. They’re unconcerned with dogmatic design principles. Benjamin and I are not really concerned with scale or convenience or order when it comes to objects or to design. We can leave that stuff to IKEA. What we want is trickery and humor and spectacle. And we want to bring absurdity to design.

-

ANNEX SUMMER 2018 Installation. Folding screen by Alina Perkins,; ceramic vessels by Brittany Mojo; aluminum stools by Skye Chamberlain; carpet by Andiseh Avini; stacking melon lamp by Michael Parker; desk by Pedro Friedeberg. Photography by Ed Mumford.

-

ANNEX SUMMER 2018 Installation. Dolphin chair by Nuri Koerfer; ceramic vessels by Fabian Marti; photograph by Matthew Brandt; carpet by Mattea Perrotta; ceramic vessels by Kelly Lamb; ceramic mushrooms by Kate Hall; carved coat hanger by Lukas Geronimas; peacock blanket by Andisheh Avini; dog-head chair by Nuri Koerfer. Photography by Ed Mumford. Courtesy of M+B Los Angeles.

What does that absurdity and that post- or non-functional design look like right now?

Right now we’re talking mostly about dinnerware objects; they create this performance somewhere between a Louis XIV dinner at Versailles and Marco Ferrari’s La Grande Bouffe (1973). None of this stuff needs to make sense immediately. There’s humor in all of the things we show.

Jay Ezra Nayssan photographedy by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP. Chair by Pedro Friedeberg.

You always use a lot of cinematic and historic references when discussing or writing about your work — from Federico Fellini to Fernando Pessoa to Roland Barthes, to name but a few. Is that how you develop and how you like to talk about your exhibitions?

An exhibition doesn’t need to look like an exhibition; it doesn’t need to be coherent. It doesn’t need to be congruent. It can read like a movie script. It can read like an unfinished book. It can sound like George Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique (1923–24). And if it pisses off people and it makes people uncomfortable, then even better. Why can’t an exhibition follow the idea of the unnarrative, the non-linear? When you're working within a gallery, it’s a cube where the white walls and everything are quite linear — why not introduce a non-linear narrative disparity of aesthetic? The idea that something feels unfinished is super interesting to me. Finality is so boring. It doesn’t offer the possibility or opportunity to evolve, to absorb somebody’s critique or admiration and build upon that. It doesn’t provide the opportunity for triviality. I want to champion a space that brings absurdity to design and elevates trickery and spectacle and humor.

Interview by Drew Zeiba.

Portraits by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.