BOOK CLUB: A Not-So-Gossipy Study of The Arensbergs’ Art CollEction And Hollywood Home

As dedicated patrons of Marcel Duchamp, during the first half of the 20th century, Walter and Louise Arensberg came to possess an enormous collection of Modern art (art advising was among the services that Duchamp provided). The couple’s collection is the subject of a new book, Hollywood Arensberg: Avant-Garde Collecting in Midcentury L.A (co-authored by Mark Nelson, William H. Sherman, and Ellen Hoobler) as is the Arensbergs’ 1920 Mediterranean Revival home, where works by Constantin Brancusi, Salvador Dali, Paul Klee, and Pablo Picasso, among others, were shown to friends, specialists, even students. Among their intellectual pursuits, the Arensbergs were also devoted believers of the “Baconian Theory,” which follows that Francis Bacon was the true author of William Shakespeare’s writings with cryptic clues embedded in the texts. And later on, the Arensbergs also became zealous buyers of Pre-Columbian sculpture. Near the end of their lives (Louise passed away in 1953 and Walter in 1954) the couple donated their Modern and Pre-Columbian collections to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and with their collection of rare Bacon books, established the Francis Bacon Foundation dedicated to furthering their cryptographic research.

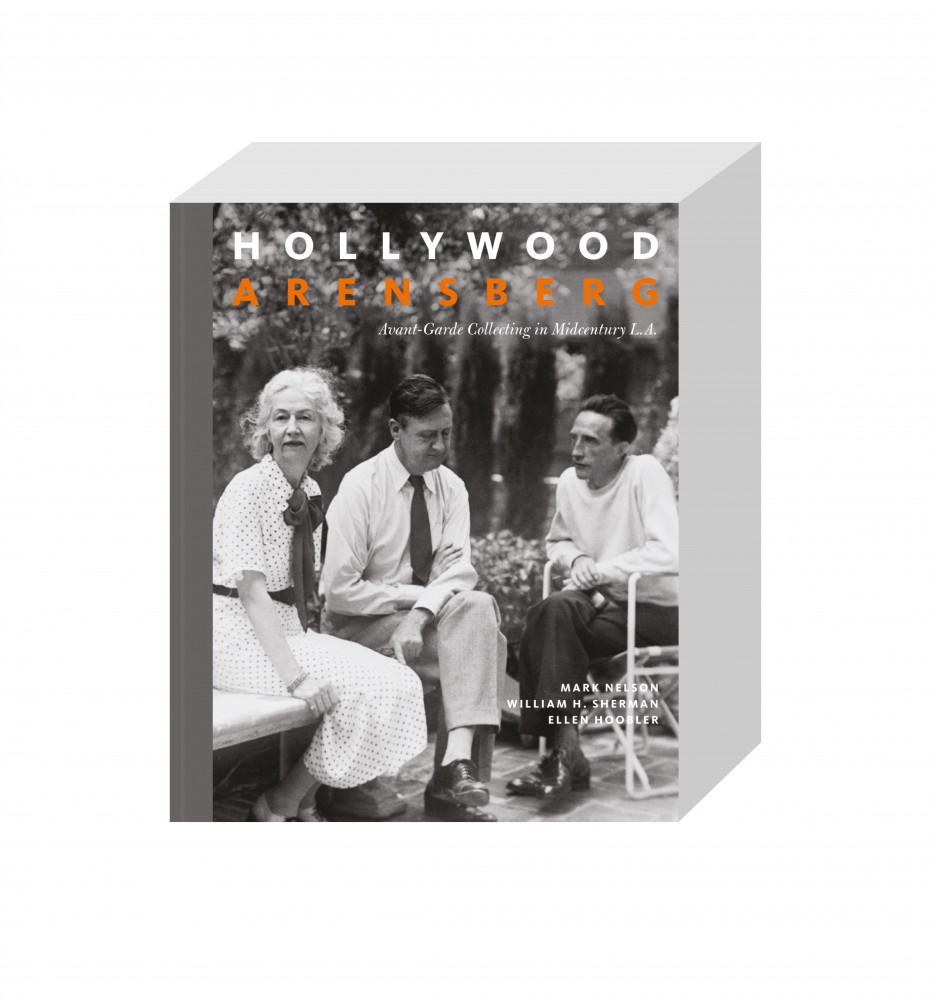

Hollywood Arensberg: Avant-Garde Collecting in Midcentury L.A by Mark Nelson, William H. Sherman, and Ellen Hoobler (Getty Publications, 2020).

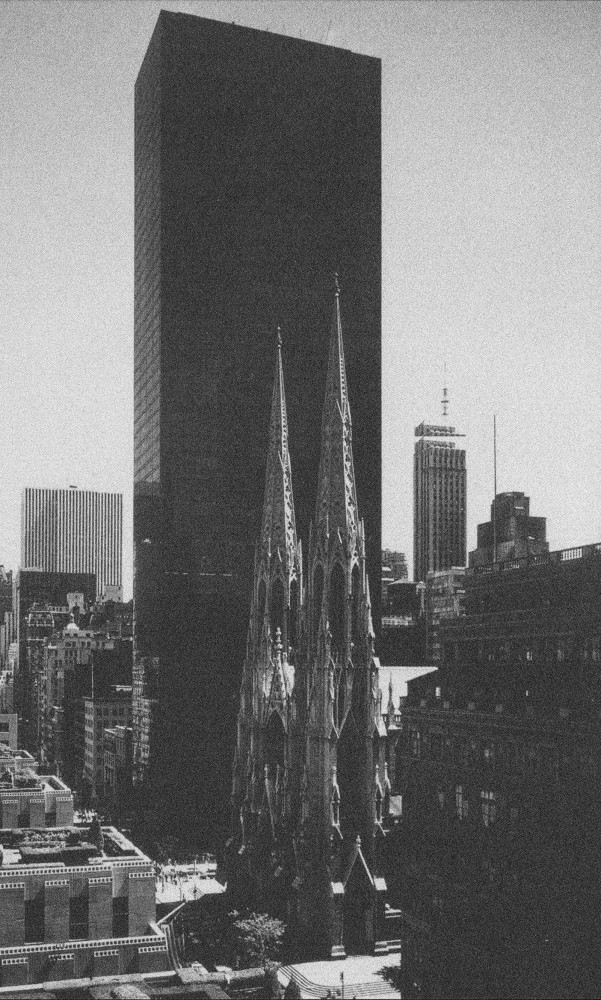

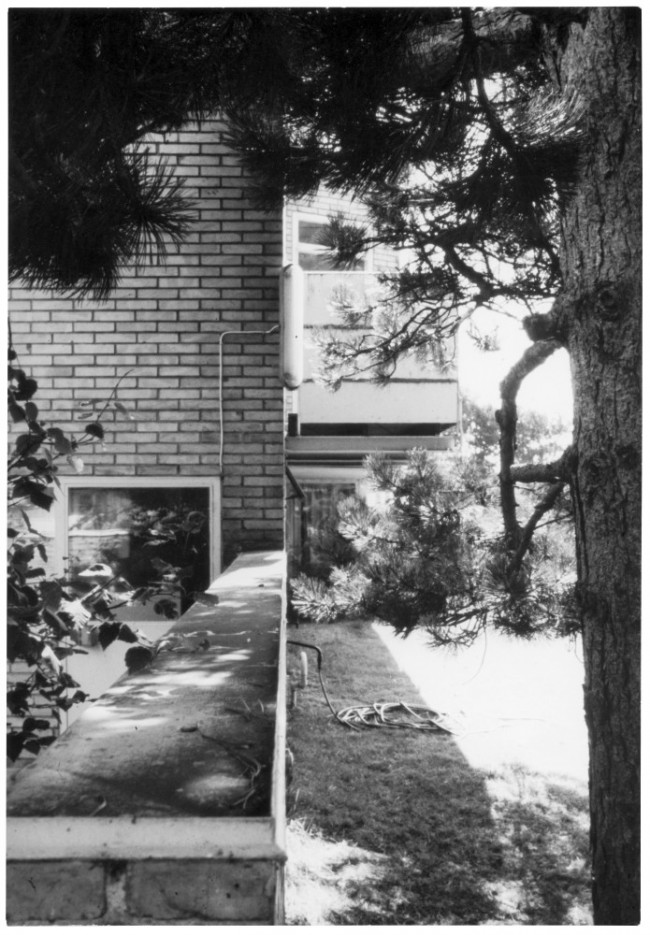

The authors of Hollywood Arensberg have produced an impressive cross-disciplinary and collaborative publication, imparting a great wealth of information while reckoning with the Arensbergs’ eccentric passions. The book is devoted in large part to photographs, floor plans, and diagrams of the interior of the house. Every artwork in the home has been painstakingly identified. Exact locations are given for each object. The overall effect is a tour-de-force of minutiae, made possible by detective-like devotion to detail. We are even given a thorough chronology of the architectural interventions over the years, including an entrance foyer by Henry Palmer Sabin (1928), a sunroom by Richard Neutra, assisted by Gregory Ain (1933), and a carport by John Lautner (1955).

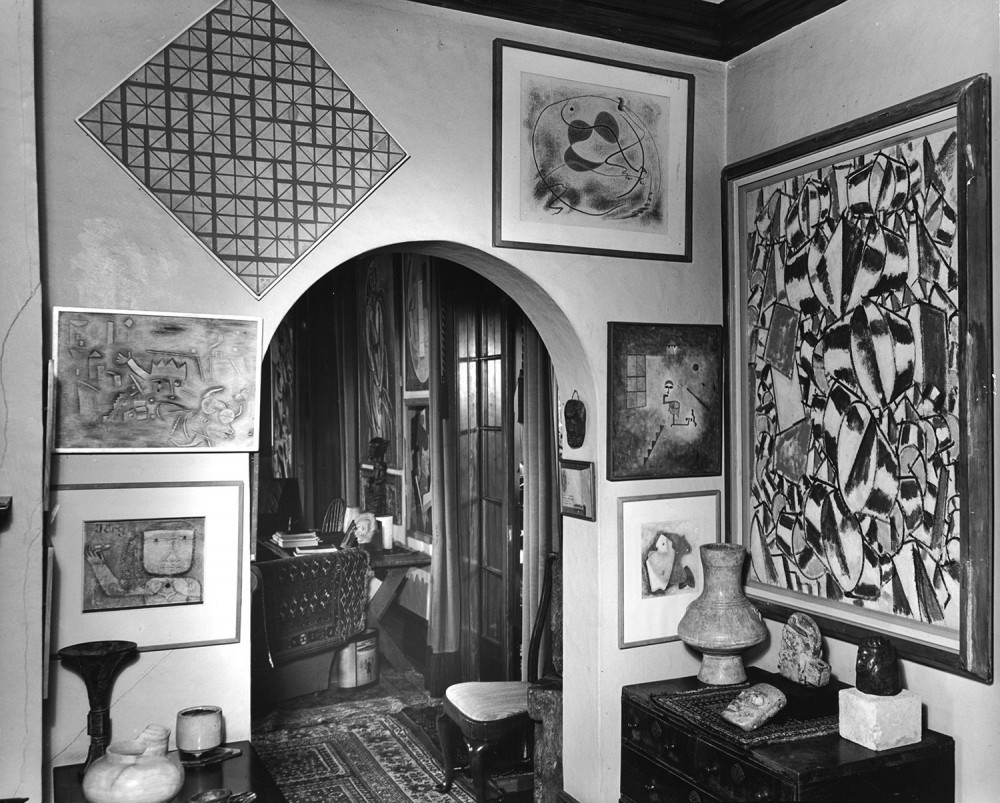

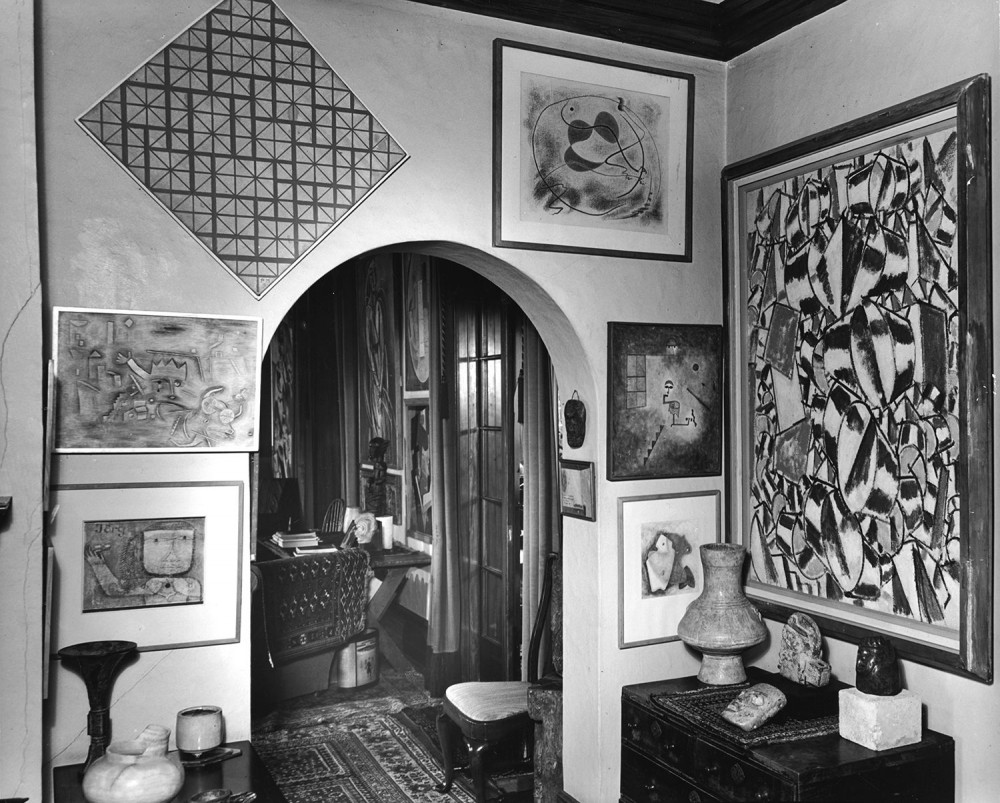

Walter and Louise Arensberg’s dining room, with a view into the living room through the north archway, ca. 1944. Photograph by Fred R. Dapprich. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives, Arensberg Archives (PMA-WLA), box 54. Paul Klee, Animal Terror, 1926, Jörg, 1924, and Prestidigitator (Conjuring Trick), 1927. Fernand Léger, Contrast of Forms, 1913–14. André Masson, Animal Caught in a Trap, 1929.

This coffee-table sized book is something of a sequel to an obscure precursor. In 1980 the art dealer and scholar Francis Naumann wrote an article for the Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin detailing Walter and Louise Arensberg’s life in New York from 1915–1920. It included a diagram of their Upper West Side apartment and a list of artworks that could be seen in photographs by Charles Sheeler. Hollywood Arensberg applies a similar method to the Arensbergs’ Los Angeles home (which they moved into in 1927) and its more expansive collection. It’s a terrific book that could be a template for other monographs about art collectors.

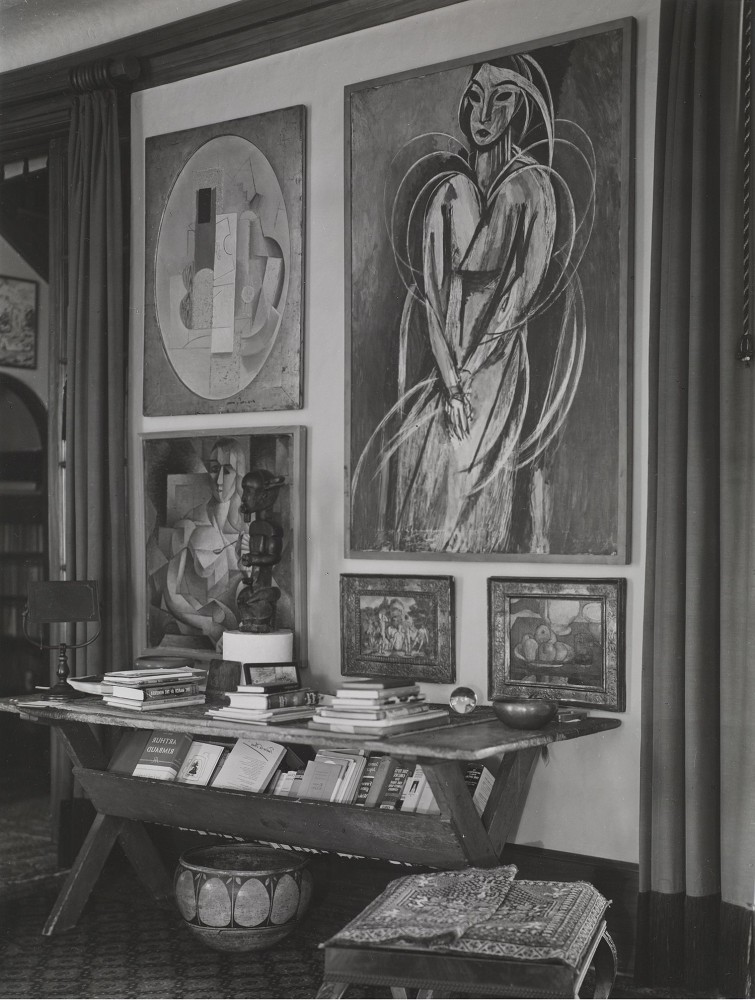

The sitting room at Walter and Louise Arensberg’s art-filled Hollywood home, ca. January 1951. Photograph by Floyd Faxon. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives, Arensberg Archives (PMA-WLA), box 54. Constantin Brancusi, White Negress (I), 1923, and Prometheus, 1911. Marcel Duchamp, Portrait of Chess Players, 1911. Francis Picabia, Dances at the Spring, 1912. Pablo Picasso, Still Life: The Table, 1921.

My only gripe is that the authors are perhaps too even-handed and too deferential to their subjects. For instance Nelson and Sherman mention only in passing that the Arensbergs left New York “on the brink of insolvency” and that “Walter philandered and drank to excess while Louise, bored, began an affair of her own.” But I wanted more gossipy details, not least of all because they offer important context. Throughout the book, the couple's proximity to an array of cultural luminaries feels obscured. There is little made of the Arensbergs’ association with architects like Neutra and Ain. Similarly, more on the couple’s Hollywood connections and friendships with actors like Vincent Price (also a collector) would help to illustrate their celebrity-adjacent influence, which ultimately must have contributed to the status of the art they championed.

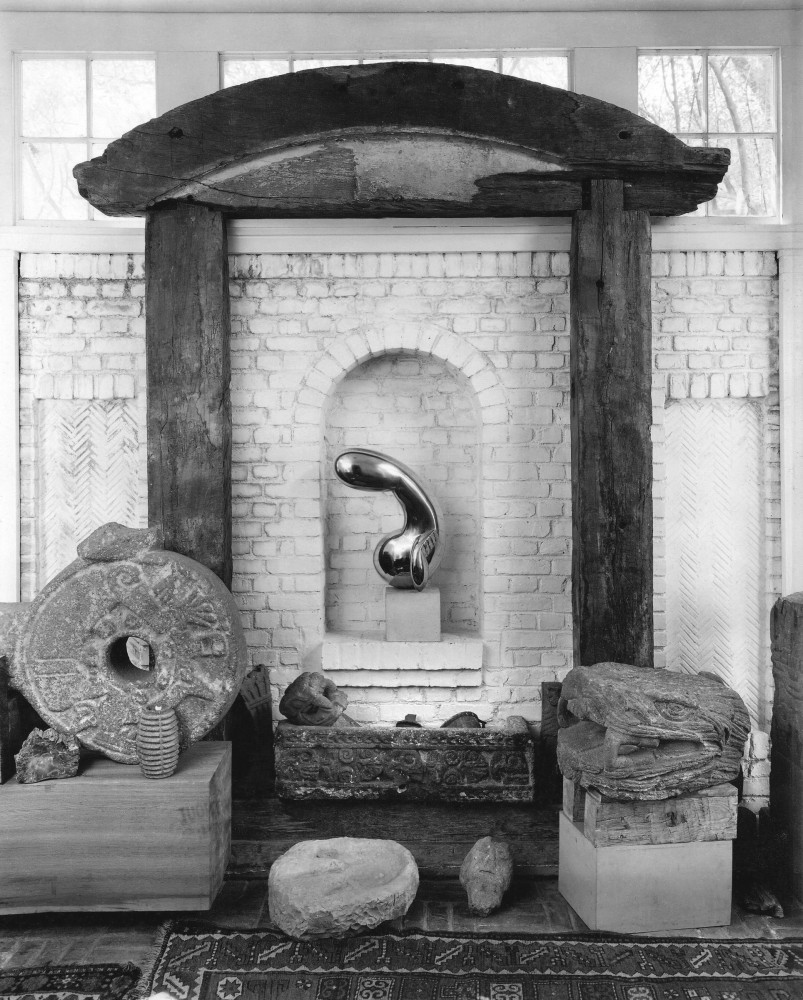

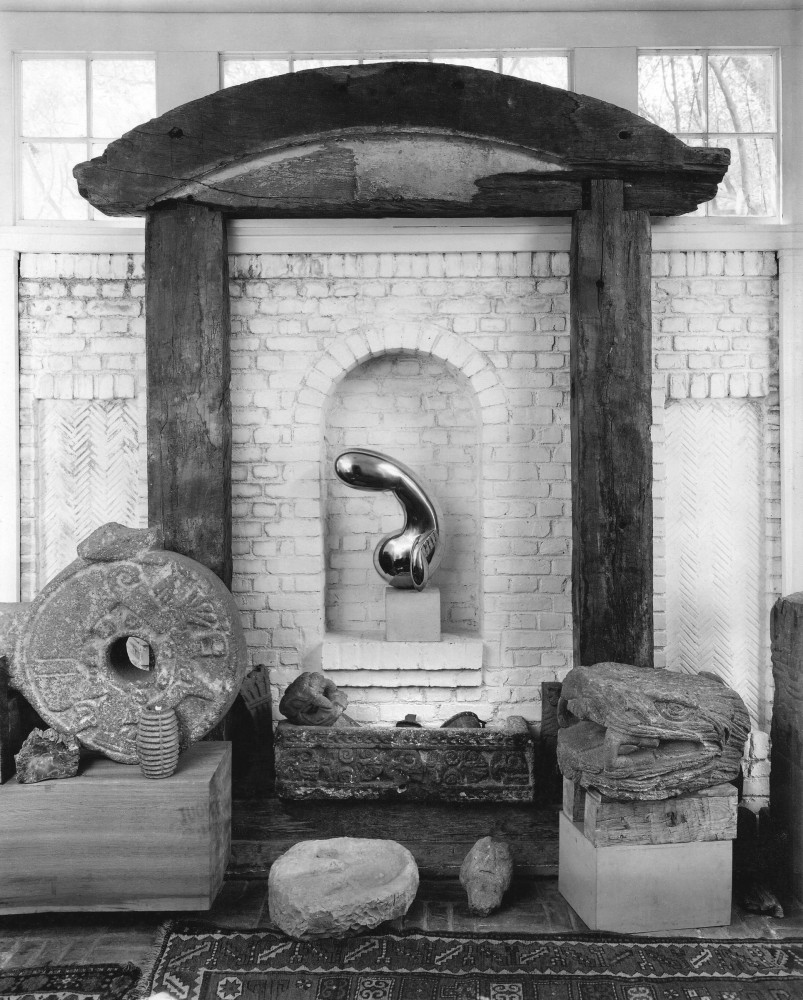

The foyer at the Arensbergs’ Hollywood home with Arch and Princess X by Constantin Brancusi, among other works — after September 25 but before October 12, 1948. Photograph by Floyd Faxon. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives, Arensberg Archives (PMA-WLA), box 54. Constantin Brancusi, Arch, ca. 1914–16, and Princess X, 1915–16.

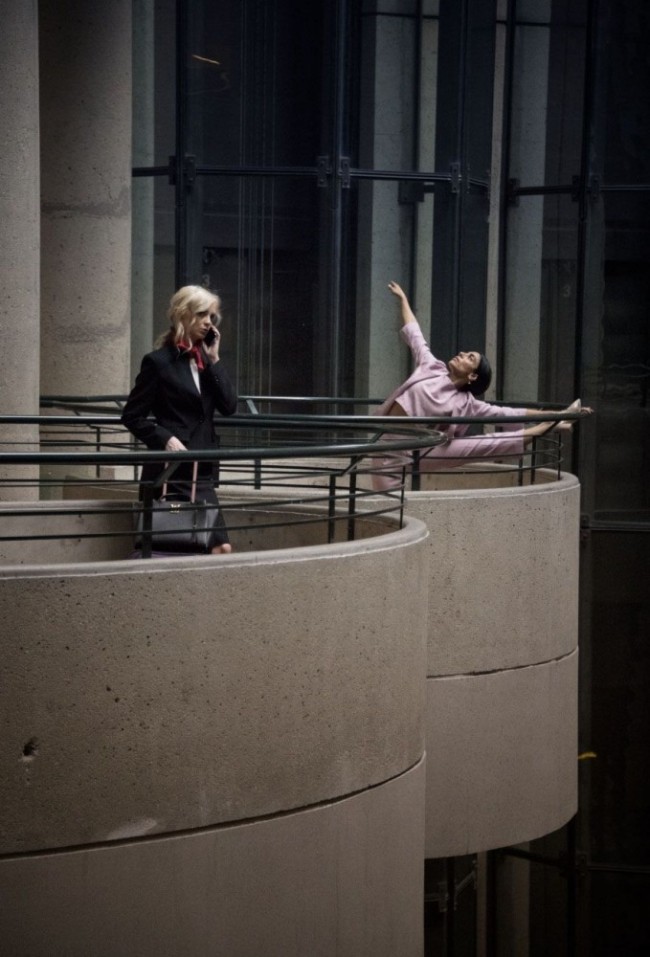

Its lack of tabloid fodder withstanding, Hollywood Arensberg is a book of extraordinary images. Among the most potentially iconic are the photographs by Floyd Faxon that document two Brancusi sculptures, specially situated in a custom-designed entrance foyer. Brancusi’s enormous wooden Arch (c. 1915) and phallic polished-bronze Princess X (c. 1915–16) were composed by the Arensbergs in a provocative arrangement that should prove stimulating for both art historians and design enthusiasts. Also incredibly beautiful are the photographs by Karl Bissinger, Fritz Block, and Fred R. Dapprich which capture the interaction between Marcel Duchamp’s glass sculpture Glider Containing a Water Mill in Neighboring Metals (1915) and the architecture of Neutra’s sunroom, which together complement a view out onto the home’s garden. Thanks to Nelson, who did double-duty as both a co-author and the book’s designer, the volume’s formal qualities help to highlight the fascinating nexus of artist, architect, and collector.

View of Louise and Walter Arensberg’s sunroom designed by Richard Neutra, showing Marcel Duchamp’s first work on glass, Glider Containing a Water Mill in Neighboring Metals, March 16, 1950. Photograph by Karl Bissinger. University of Delaware Library, Newark, Special Collections, Karl Bissinger Archive (MSS0682). © Estate of Karl Bissinger.

While Hollywood Arensberg might appear to be an excessive exercise in train spotting for art junkies and design obsessives, it is in fact a book with consequences for art history and politics more widely. The history of collecting is a burgeoning field and not just because people like to look at nice houses. As we wrestle with questions about who the museum is for and how the art canon became so slanted (favoring the rich, white, and male) we must revisit the patrons and collectors who have played a role in art history’s evolution. This book starts to fill in one of the major gaps that exists in our knowledge. We find out about the life of art objects after they leave the artist’s studio and before they enter the art museum. For this reason Hollywood Arensberg is an instant classic for a nascent field.

Text by Robert McKenzie.

Images courtesy of Getty Publications.

Rob McKenzie is the co-author with Paul Foss of The &-Files: Art and Text 1981–2002 and works as a curator and art market expert in New York.

Hollywood Arensberg: Avant-Garde Collecting in Midcentury L.A by Mark Nelson, William H. Sherman, and Ellen Hoobler (Getty Publications, 2020).