NUDISM AT CAP D’AGDE: Sea, Sex, And Sun, In The Name Of Utopia

Héliopolis means city of the sun in Greek. There are two in France, both on the Mediterranean coast: one on the Île du Levant, near Hyères, the other at Cap d’Agde, an hour’s drive west of Montpellier. Both were founded by brothers, and both are iconic destinations for naturists.

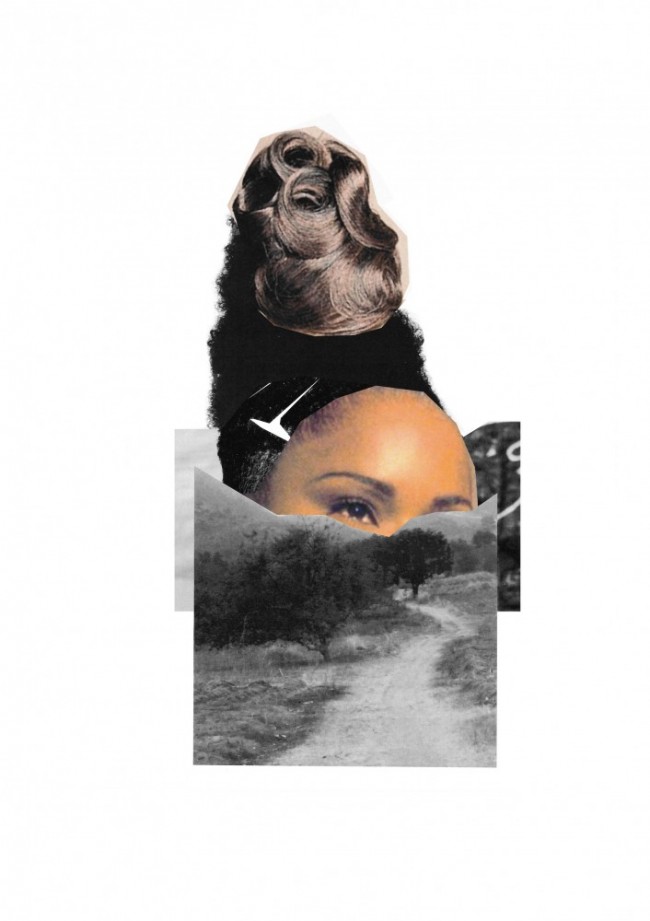

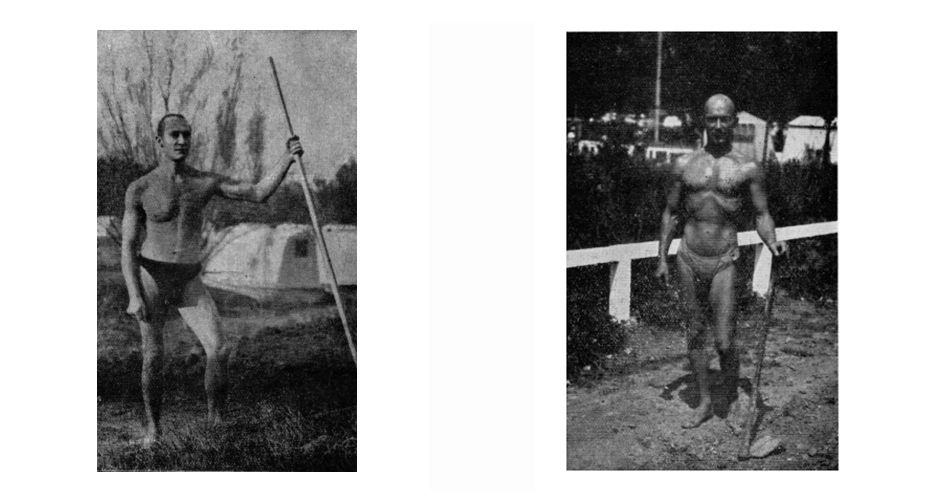

The brothers André and Gaston Durville (left to right), who in 1928 started the naturist campsite Physiopolis on Ile de Platais near Paris, an antecedent to Héliopolis in Cap d’Agde.

The first French Héliopolis was built in Levant in 1931, created by Gaston and André Durville, Parisian doctors who supported alternative medicine, founded the Society of Naturism, and edited its influential periodical, Naturisme. Sons of a famous occultist and magnetizer, the Durville brothers defended a way of life close to nature based in physical activity and exposing the body to the sun, water, and air. Their first endeavor, Physiopolis (city of nature), located on an island in the Seine near Paris, was essentially a weekend and vacation campsite founded in 1928. No doubt seeking better weather for an extended season, as well as a more isolated location, the brothers shifted their attention to the “Physiopolis of the South,” as Héliopolis was first billed, where their growing base of urban followers could practice their still controversial naked health routines at greater length and liberty. Héliopolis’s early days were a great success: a bakery, post office, bar, and (vegetarian) restaurant were built for the first summer, which allowed residents to settle and also to welcome visitors. Most of the building plots (unlike Physiopolis, the settlement was to have real houses) sold out in the first year. The “greatest international naturist center in the world,” as the Durville brothers dubbed it, was one of the most tangible European manifestations of the body-conscious heliotropism that underlay much Modernist social-utopian thinking at the time. Somewhere between a commune, a sanatorium, and a Robinsonade, Héliopolis found its echo in the early days of Californian Modernism, where Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra built beach houses, health houses, and gyms for the naturopathic naturist Dr. Philip Lovell, who was a regular patron of John and Vera Richter’s vegan raw-food restaurant, the Eutropheon.

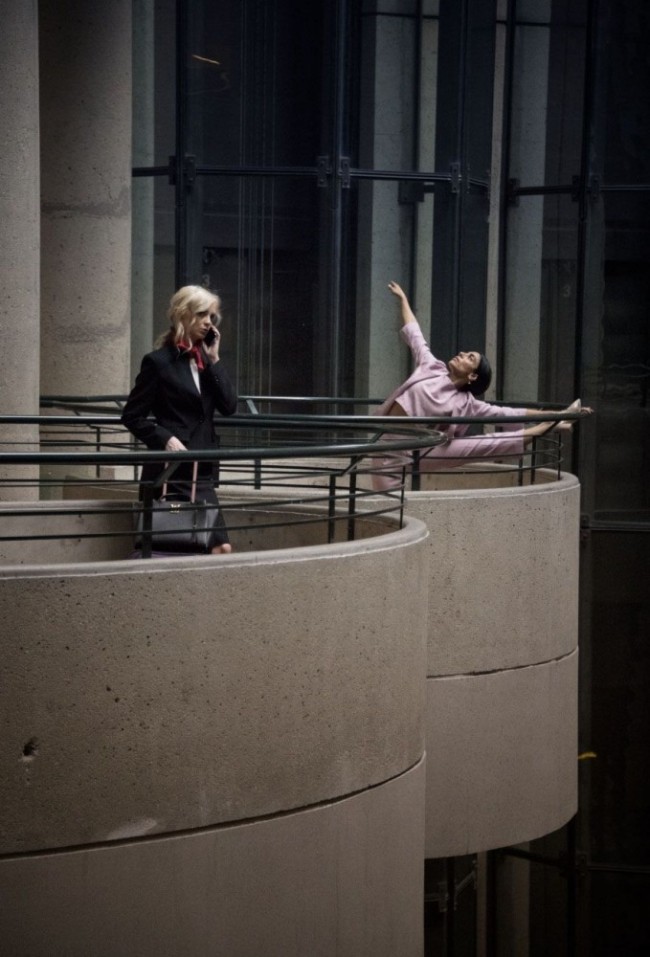

An archival image of an unclothed guest posing on a balcony at Héliopolis in Cap d’Agde.

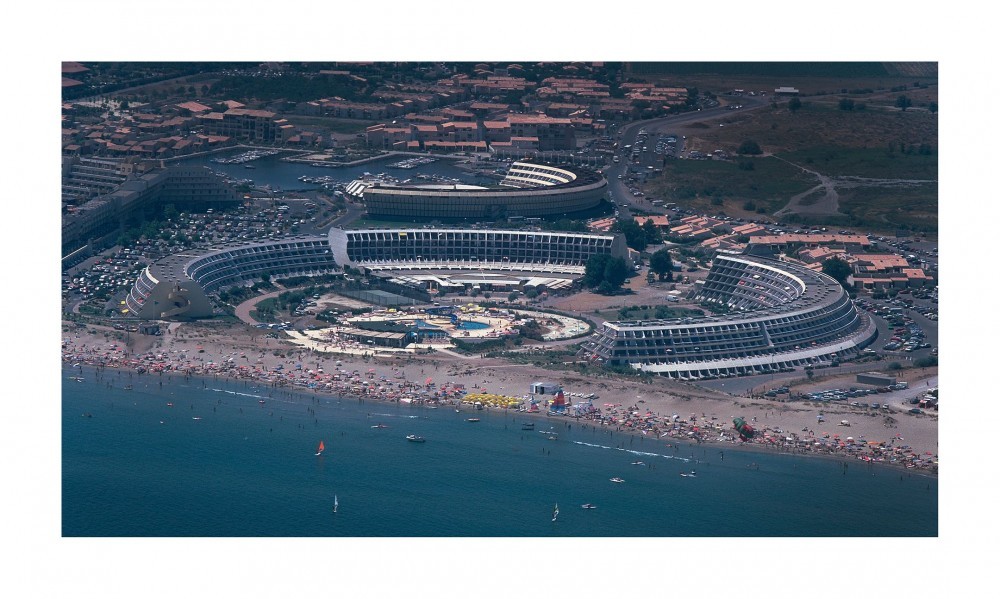

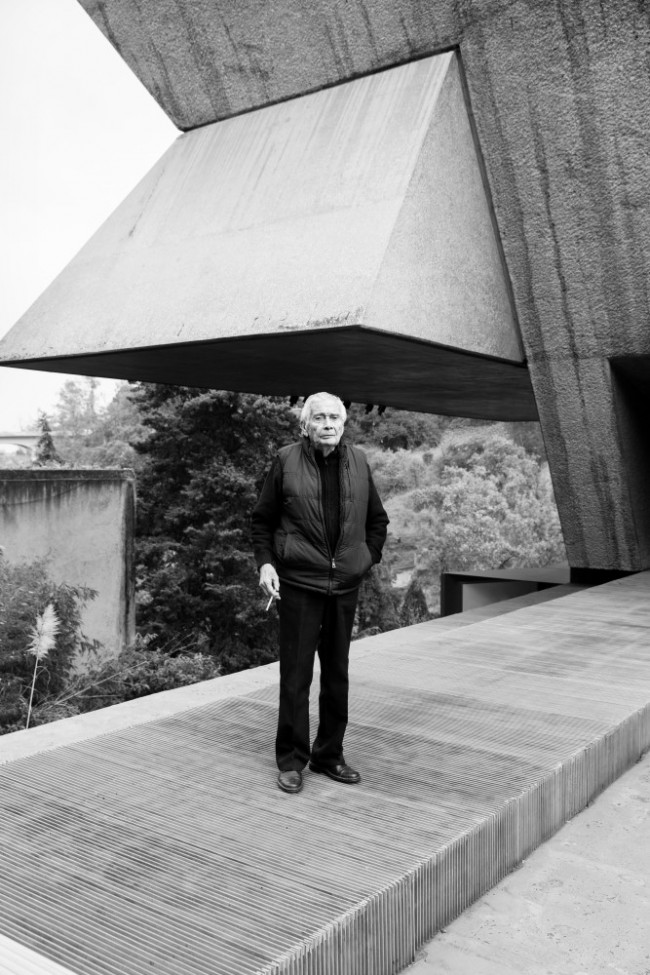

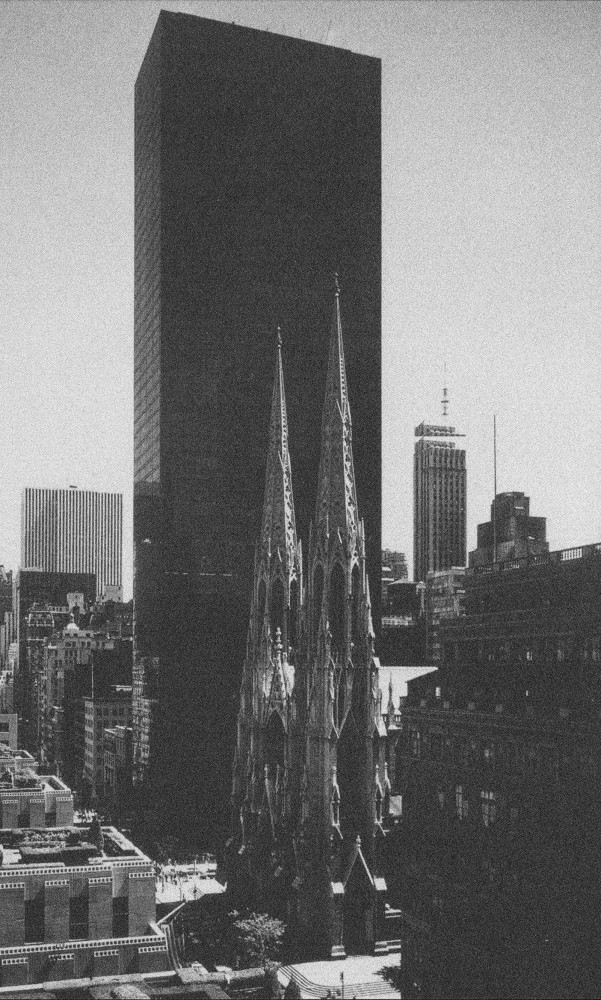

Although France’s first city of the sun spawned no architecture of note, it lent its name to part of another nudist colony that did: the village naturiste at Cap d’Agde, which has been the largest in the world for the last several decades. At Cap d’Agde, Héliopolis is the name of the village’s most monumental building: designed by local architect François Lopez in 1975, it takes the form of a four-story, 3,000 foot-diameter, horseshoe-shaped residential block which opens onto the beach, its façade angled so that each apartment receives maximum sun exposure. At the center of this Modernist panopticon-colosseum for nude living are a bar (Le Bangkok), a restaurant (La Moule d’un Soir), and a nightclub (Le Glamour Beach), as well as a private pink-tiled pool club (Le Jardin d’Eden), which today all cater to swingers. The Héliopolis building in Cap d’Agde is the unexpected result of two visions of holiday resorts: naturist idealism and state-led vacation urbanism. Cap d’Agde is one of seven mass-tourism beach resorts planned by General de Gaulle’s government in the 1960s on the coast of Languedoc-Roussillon, between the Rhône delta (Camargue) and the Spanish border. Known as the “Mission Racine,” after its director, Pierre Racine, it remains one of the largest postwar infrastructure projects undertaken in France, with facilities for half a million holiday-goers having been constructed between 1963 and 1983 in inhospitable mosquito-infested marshes (15 percent of the overall budget was allocated to eradicating mosquitos).

Aerial view of Héliopolis designed by François Lopez in 1975.

It was in this context that brothers Paul and René Oltra transformed the naturist campsite they had founded in 1956 into a giant beach resort. They employed Lopez — who was working alongside Jean Le Couteur, Cap d’Agde’s architect in chief — to help them build the largest naturist colony in the world, centered around three massive concrete buildings located away from the textiles (naturist jargon for people who wear clothes) behind gates, a harbor, and dunes. Between 40,000 and 50,000 naturists gather there each summer, half of them in Modernist architecture (Héliopolis alone can accommodate 5,000), half of them in camping bungalows. The 1970s and 80s were the golden age of Cap d’Agde’s naturist colony. It was championed by the local authorities because of its profitability and dominated by a rather chaste family naturism. But, by the early 90s, sex had become the resort’s main raison d’être: the clubs now welcome swingers, shops sell kinky gear among the groceries, and the beach is home to an internationally famous summer-long orgy that reaches its apogee in the dunes of the Baie des Cochons (Pigs’ Bay), with endless open-air group sex and bukkake. Several pages are devoted to Cap d’Agde’s late-modern condition in Michel Houellebecq’s 1998 novel Atomised, which describes the architecture, the clubs, the sex, and the fortuitous geography of the site as “an idyllic phalanstery out of Fourier.”

-

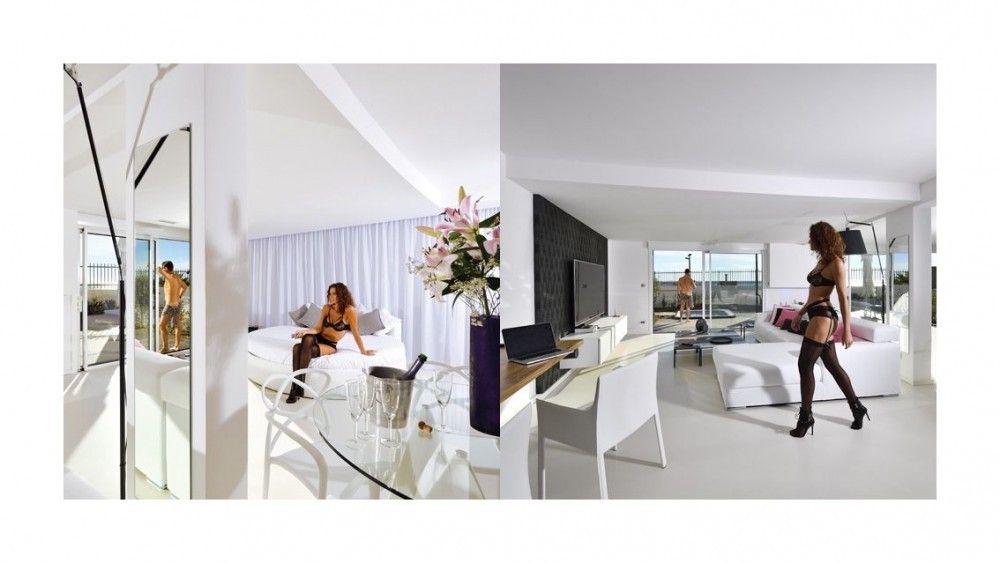

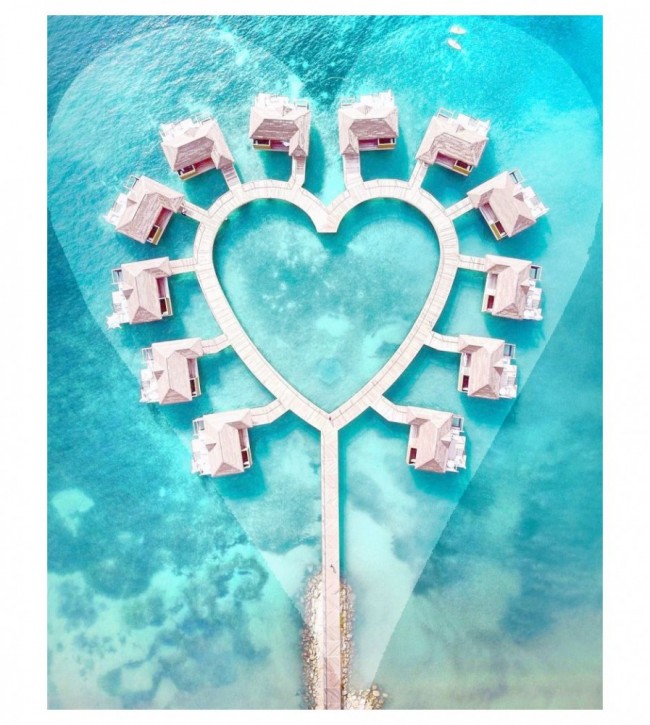

Cap d’Agde rentals marketed to swingers.

-

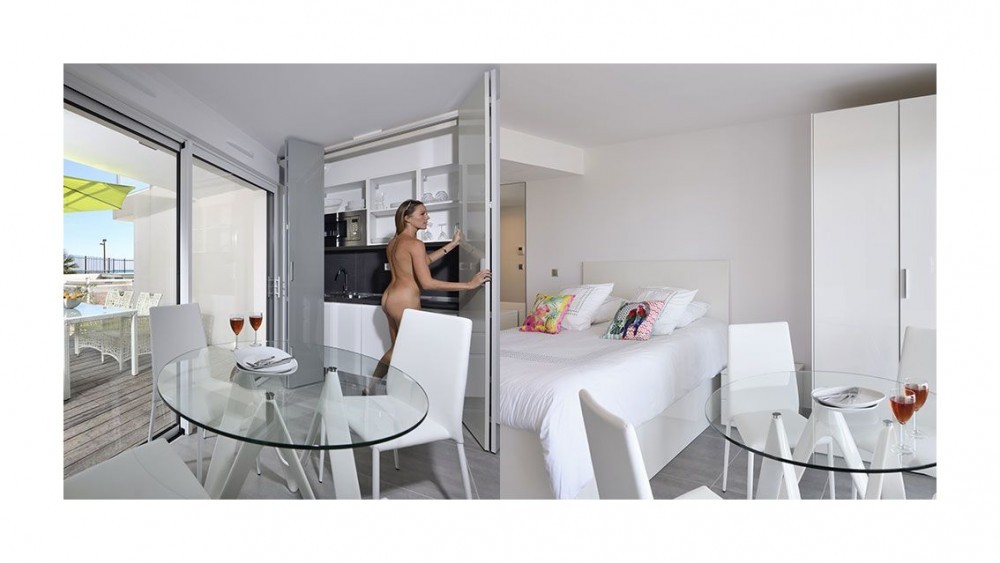

Cap d’Agde rentals marketed to swingers.

-

Cap d’Agde rentals marketed to swingers.

Although business is still pretty good at Cap d’Agde’s village naturiste, things at Héliopolis are said to be different today. Naturists are aging, and so is the architecture. Gendered swinging is not so aspirational and porn sexuality is not so utopian, especially in the context of a rise in incidents involving non-naturist male opportunists. Furthermore, many now prefer newer resorts in Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, or Eastern Europe. Cap d’Agde’s village naturiste may end up simply being absorbed into the rest of the resort — unless a critical mass of sex-positive porn-friendly queer youth takes over the site, though they may be better off building their own Héliopolis somewhere else.

Octave Perrault is an architect based in Paris. Curators Pierre-Alexandre Mateos and Charles Teyssou invited Perrault to visit the Cap-d’Agde offseason in Decembre 2017 as part of their residency at the LUMA Foundation in Arles. Soon after, they started working together on Cruising Pavilion, an exhibition series about gay sex, architecture, and cruising cultures.

All archival photography sourced by Pierre-Alexandre Mateos and Charles Teyssou.

Taken from PIN–UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.