A Show at the Schindler House Harnesses The Soft Power Of Plural Storytelling

When I arrive in West Hollywood to walk through Soft Schindler, a design exhibition curated by Mimi Zeiger at the early Modernist landmark Schindler House, it’s full of activity. In preparation for an event celebrating architectural historian Esther Choi’s cookbook Le Corbuffet, people are passing from room to room, setting a table, cooking in the kitchen. It’s a fitting introduction to an exhibition about taking time to enjoy a domestic space.

Zeiger’s curatorial mission for the show is based on rendering plural the story of the historic home, designed in 1921 by architect Rudolph M. Schindler. While today it’s one of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture’s three Los Angeles venues, the house was built as an experiment in communal living. Austrian-born Schindler conceived of the space as both residence and workplace for himself, his wife Pauline, and another couple, Clyde and Marian Chace, the bungalow’s pinwheel layout incorporating four studios, outdoor sleeping porches, a shared kitchen, and a guest house. (A nursery was added later.)

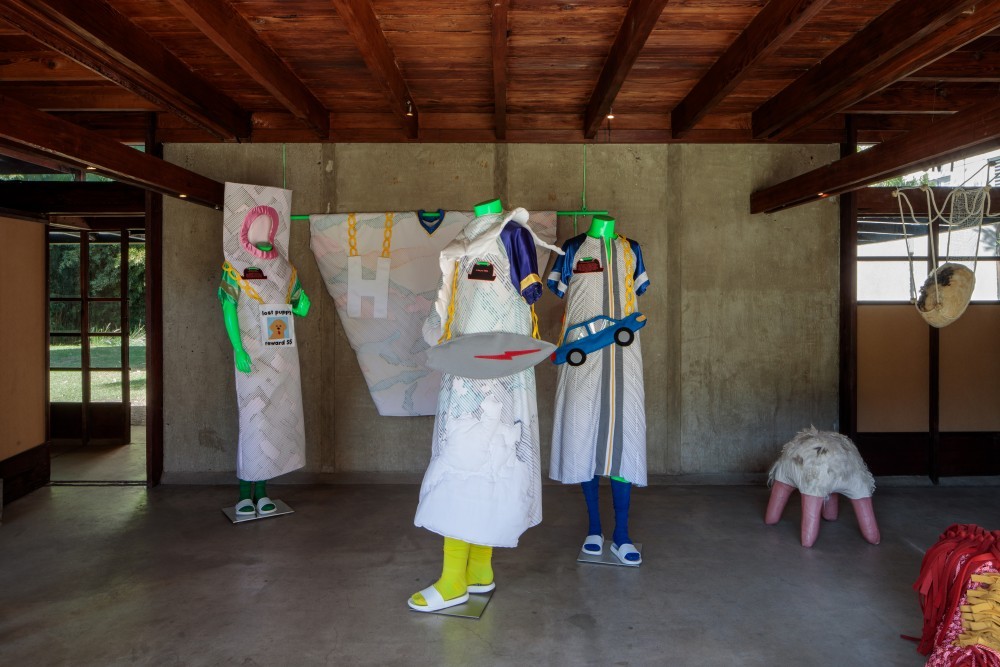

Pedro Alonso and Hugo Palmarola, Choreographies, 2016. Photo © Taiyo Watanabe. Courtesy of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

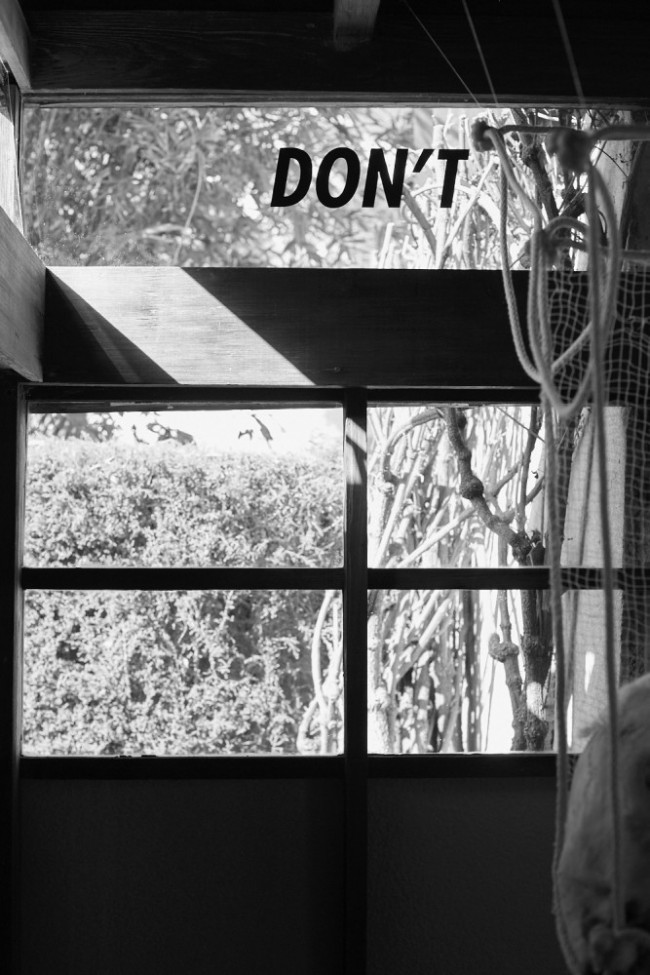

Zeiger’s desire to invite in less common readings of the space came from discovering vestiges of pink paint on the Schindler House walls, and wondering what other stories the house might tell. Pauline and Rudolph separated in 1927 but in an unconventional arrangement, Pauline moved back into the home in the 1930s and painted pink her half of the house (the quarters originally designed for the Chace couple). Zeiger explains that the challenge of installing multiple audio works in the show without aural overlap — including a sound collage by Jorge Otero-Pailos which plays recordings of Merce Cunningham’s rehearsal studios, and an animated diptych video by Pedro Alonso and Hugo Palmarola — made her keenly aware of the house’s architecture too, which “is remarkably resilient” and expressly “designed to allow for distinct spaces.”

In conceiving of the show Zeiger describes that she was trying to figure out “how do you create work that is embodied — that is not just material but an experience as well?” One solution is immediately offering visitors a place to sit, ensuring that comfort and care are more than just conceptual considerations. An installation by Sonja Gerdes in the nursery room of the house requires visitors to sit or lie on a pink carpet in order to listen to its accompanying sound piece. (It’s the chill-out tent to Soft Schindler’s music festival.) Visitors are also encouraged to touch Bryony Roberts’s readymade-assemblage Felty: a textile piece draped invitingly over a reproduced Schindler chair. It’s a moment that plays with our expectations given that the real Schindler chairs in an adjacent room of the house are not to be touched.

Sonja Gerdes, Pie of Trouble. Stays Trouble. Belly on Belly. Let’s Hang. Breathe you infinite. Animal Creature Plant Breath Soul. The Energy Plan. Amorphous Hypersensibility. Do Spiders Breathe? Mothersmilk. The Multiple Amorphous Us. Air For Free., 2019. Photo © Taiyo Watanabe. Courtesy of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

The interaction between the exhibition’s works and the Schindler House’s architecture prompt radical ideas about the future of domestic living. Architect Anna Puigjaner’s ongoing research on “kitchenless” housing is presented through illustrations that consider what it could mean to take the kitchen out of the single family home. While Fermentation 01, a culinary experiment in which recipes by foodies Ai Fujimoto and Jessica Wang are fermented over months in marble block vessels designed by architects Leong Leong, turns one of the home’s patios into an outdoor kitchen.

-

Leong Leong, Fermentation 01, 2019. With fermentations by Jessica Wang and Ai Fujimoto. Photo © Taiyo Watanabe. Courtesy of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

-

Leong Leong, Fermentation 01, 2019. With fermentations by Jessica Wang and Ai Fujimoto. Photo © Taiyo Watanabe. Courtesy of the MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

Leong Leong describe these fermentation vessels as inhabiting a playful space between sculpture and tool. The architects gesture at ideas of experimentation and liminality that apply to the show as a whole which, by requiring active engagement, turn the viewer (of a sculpture) into a user (of a tool). Soft Schindler makes a case for the power of plural approaches to living, and makes room for softness and slowness. The Schindler House is many things; Soft Schindler suggests we stay in to see them.

Text by Emma Leigh Macdonald.

Installation photography by Taiyo Watanabe.

Soft Schindler is on view at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles at the Schindler House until February 16, 2020.