EIGHT CREATIVES TALK ABOUT THE PARADOX OF COMFORT

According to the 1995 article The Paradox of Comfort in the journal Nursing Research, “comfort is not an ultimate state of peace and serenity, but rather the relief, even temporary relief, from the most demanding discomfort.” Rather than providing comfort, medicine’s stated goal is the minimization of discomfort. In that sense comfort is the state we attempt to arrive at by living with a body — even one that is in some way disabled — without being dominated by it. This opposition is part of the paradox of comfort: we seemingly can’t define comfort except by what it is not. So often architecture and design are required to produce (or to fail to produce) comfort, whether it’s the overstuffed upholstery or mattresses that promise perfect relaxation, or the “hostile architecture” created to be intentionally uncomfortable (think anti-homeless spikes). For PIN–UP, eight architects, artists, curators, and designers offer their personal vision of what to them embodies the comfort paradox. From genre-defying household objects to devices that create both physical anxiety and relief, each one pushes us well outside of our “comfort zone.”

SAM CHERMAYEFF

Architect and cofounder of June14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff, Berlin, Germany

June 14Meyer-Grobruegge and Chermayeff, Triangular bed, 2014. Photographed by Luca Girardini.

Comfort can be about possibilities, paths of escape, and freedom. Comfort can grow from clarity, support, and the familiar. Our triangular bed from the series For the Nuclear Family and Its Opposite Together (2014) concerns itself with the coziness and the unknown at once. A giant soft triangle lets you lie in a lot of different ways. The shortest side is really very long. Nearly independent activities can happen all at once here but it remains one space. Most rooms are rectangular. With the triangle a room becomes four spaces: the bed itself, and the other three, one per side. A rectangular bed, by contrast, makes just one space. It is all bedroom. Comfort on and around the triangle becomes very specific when other programs emerge. Each person does something different on each side. There is usually a place for a desk somewhere, a place for a wardrobe, a place for a chair, and so on. The key to being comfortable is being flexible of course. You make peace with the fact that on the very same spot you might have an orgy one day or simply cuddle up with a few of your kids the next.

NICHOLAS GARDNER AND SASA STUCIN

Designers and founders of Soft Baroque, London, United Kingdom.

Image © NASA.

If we analyzed comfort in a direct way, we could use the formula: comfort is proportional to the amount we can distribute our mass over a surface area. Think of an animated diagram in a mattress advertisement, a cross-section displaying an androgynous computer-generated figure with butt, spine, and foot support pulsing with soft red and blue gradients — ‘complete support.’ Beanbags, hammocks, La-Z-boys, floating sensory deprivation pods, and ball pits are geared towards minimizing the earth’s gravitational effect on our bodies. In the same way a walrus has evolved to have a layer of blubber for the cold, common furniture has been designed for maximum comfort. People cherish fully upholstered sofas in a desperate attempt to never be in contact with anything that has a shore hardness greater than skin. If gravity is the only thing getting in the way of true comfort, then in a low-gravity environment, such as the International Space Station or the moon, what criteria are we left with to judge comfort? In the emptiness of space, the most comfortable place humans have ever experienced, there is a sense of unease. In the words of Mike Fossum, a former Space Station astronaut: ‘I will get the sleeping bag all zipped up and the bungee holds a little bit of force, holding me up against the wall. It makes me feel a little bit like I’m back home, in bed.’ It’s a paradox: part of us wants to escape the pain of gravity, and yet we can’t find comfort without it. We’ve all seen images of astronauts shakily climbing out of a shuttle after re-entry, acclimatizing to weightiness — like coming down from a high, too much of a good thing. If common sofa design, in response to the problem of gravity, results in fat folds of leather-upholstered memory foam with down throw cushions, what will we have to construct to be comfortable when we eventually populate zero-gravity environments? Maybe a series of harnesses and tethers that try to inject an evolutionary need to feel the earthly pull? A bed that spins at a critical number of revolutions per minute to create centrifugal force, Gravitron style? Or will it be stylistically referential to earth conditions, a sort of gravity nostalgia? We can’t wait to find out.

OLALEKAN JEYIFOUS

Artist, Brooklyn, USA

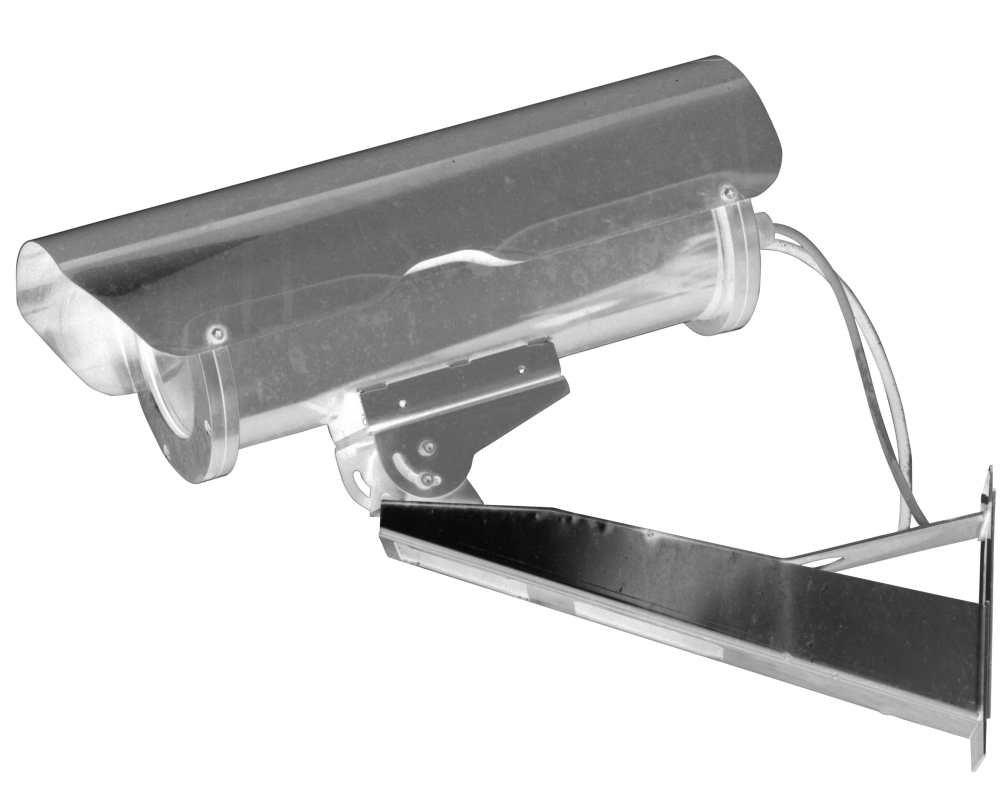

I was born in Ibadan, Nigeria, to an American mother and a Nigerian father, and settled in the U.S. for good when I was six. From then until I attended college, my life was marked by constant moving and perpetually adapting to new places. As a result, much of my work responds to either the anxiety or potential of certain spaces, and how one navigates, maps, and perceives them. The speculative architecture I create reinforces this notion, and is often wrought with a synthesis of utopian or dystopian ideals that employ ‘failure’ as a conceptual catalyst. When considering the socio-economic conditions and/or geo-political issues my artwork frequently responds to, I’m reminded of a quote from Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale: ‘“Better” never means better for everyone... It always means worse for some.’ As an example, one need look no further than our current neo-McCarthy-like government which has far exceeded its predecessors in its disregard for the civil liberties of marginalized communities, the blurring of lines between public and private, or the increasingly abiding faith in technology which enables the perception of its sophistication to confer validity, invoking a near ubiquitous trend towards total surveillance. The ‘failure’ on the part of numerous urban development practices to adequately consider the needs or even the existence of disenfranchised communities, instead reproducing the repressive aspects of economic deprivation and political marginalization, is in many instances an intentional by-product of a self-replicating and aggressively capitalist system that serves precisely who it was intended to.

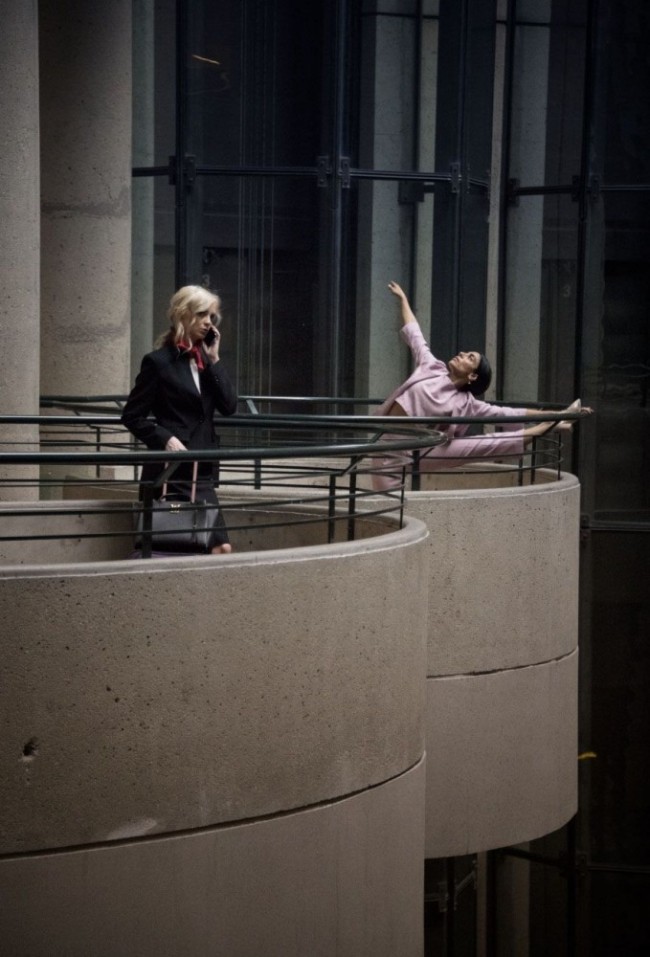

MARIA CRISTINA DIDERO

Design writer and curator, Milan, Italy

Atelier Biagetti, Tornello table, 2017.

A table formed of a turnstile in chrome-plated steel, finished with brass-coated edges, and topped with an oval-shaped piece of ultra-white glass: if the structure is reminiscent of a supermarket, waiting in a line might have never been so luxurious. The object, called Tornello (turnstile in Italian), is part of a body of work by the Milan-based design studio Atelier Biagetti, headed by Laura Baldassari and Alberto Biagetti. It is also part of GOD, the third episode in a trilogy that I had the pleasure (and fun) to curate over the past three years with Laura and Alberto. Together we analyzed a number of contemporary society’s greatest obsessions via immersive, experiential design projects comprising furniture and performances. Atelier Biagetti’s approach is unique, and so are the objects originated by their practice. After BODY BUILDING (2015), which looked at the obsession of fake beauty in our era and NO SEX (2016), which teased the idea of being addicted (or not interested at all) in fornication, GOD tackles contemporary society’s real deity: money. While the name evokes religion, icons, and values of morality, its true declared meaning was legible through the environment created by Atelier Biagetti as a place where the rites and rituals associated with money were carried out through objects in a very playful though respectful way. The Tornello table — in keeping with the exploration of the sensibility of human beings towards money, wealth, competition, market rules, and social climbing — boldly expresses the dichotomy between the comfort of a well-designed object and the discomfort of its conceptual critique. As the authors say, Tornello ‘investigates how the idea of money can reverse any process, making the uncomfortable comfortable and vice versa.’ But philosophy and speculation aside, if you really want to have a seat at this table, you should be comfortable enough to shell out 20,000 euros.

MIMI ZEIGER

Architecture writer and curator, Los Angeles, USA

Frank Lloyd Wright, 606 Barrell Armchair 1937/1986. Available through Cassina.

As busy, busy people who move through the world and occasionally need to sit still, we have a tacit understanding that furniture should be, if not comfortable, at least neutral — ready to accept the buttocks of any size, gender, race, or orientation. Beautiful designs tempt us into repose. However the conceit of universal design is upset when we are forced to recognize that not all bodies fit in or are supported by the most elemental of objects. So when, earlier this year, Hunger and Bad Feminist author Roxane Gay was fat-shamed for requesting a chair sturdy enough to support her frame and outcry ensued against this affront on body acceptance, I was also shocked by how a simple function — sitting — could be weaponized against bodies. It’s with Gay’s incident in mind that I approached maneuvering my wide hips into the dimensions of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Barrel chair. Low ceilings are generally cited for the architect’s famous disregard for bodies other than his own, his sense of scale being modeled on his (alleged) 5-foot-8-and-1/4-inch height. Designed in 1907 as part of the custom furniture of his Gesamtkunstwerk, Darwin Martin House in Buffalo, the Barrel chair is one of his most popular designs, often replicated in its nearly circular geometries. Settled into a reproduction of its oak corseting and obliged thereby to adopt a morally good posture, I imagine other people, other soft bits, shifting uncomfortably against the constraints of universality, yet comforted by the allure of an icon.

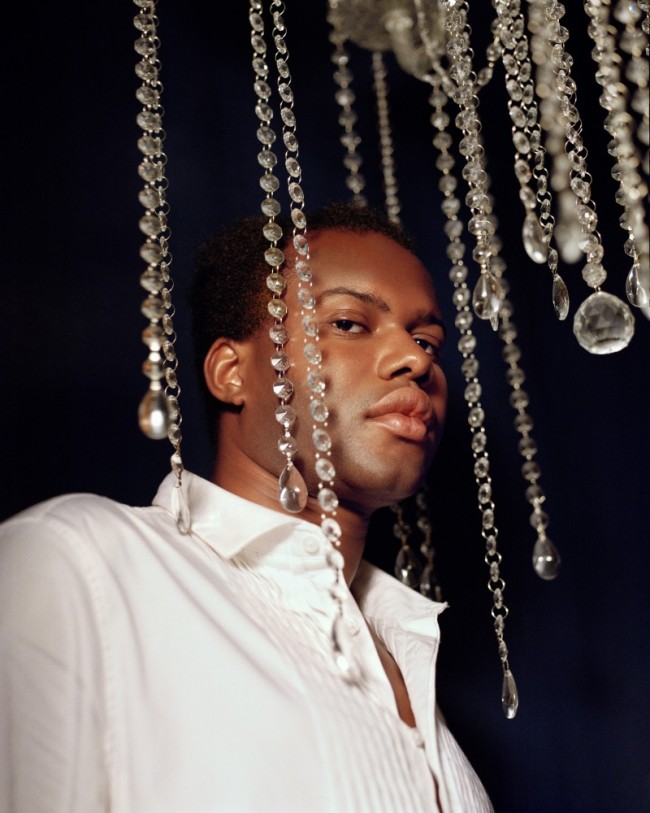

GABRIEL HENDIFAR

Designer and cofounder of Apparatus Studio, New York City, USA.

Khatam Box photographed by Antwan Duncan for PIN–UP.

I am on a plane as I write this, which feels fitting because I’ve recently begun to understand that I exist in a liminal state. I’m a first-generation American, born in Los Angeles to parents who fled Iran in 1979 on the eve of the Islamic Revolution. My warmest memories of childhood are centered around large family gatherings. My grandmother would peel platters of fruit to be passed among guests and my mother would be coaxed to the piano to sing songs from a place I had never been. Everyone would join in the chorus, with distant gazes, in a form of collective mourning for somewhere that no longer existed. As a young child I was very close to my grandmother, Shazdeh, who lived next door in our duplex. She would take me on walks around the neighborhood and tell me stories of this faraway place — about her beloved brother who was creative like me, and who died in Iran before I was born (was he also gay?); about summers in the country; and about her childhood in Shiraz. As I grew up, I assimilated. I distanced myself from a heritage that I only knew through food, music, and stories. I felt that it wasn’t mine, and that I needed to shed its weight to form my own identity. I visited family less, finding myself uncomfortable speaking Farsi unless I had to. Yet I would never really feel American either. When my grandmother died, my mother asked if there was anything of hers I wanted. I took a long leopard-print cardigan and a housedress that I remember as her uniform. I also took a box that she had brought with her from Iran, covered in an intricate style of marquetry called khatam that was made popular in her birthplace of Shiraz. It was tucked away high in her closet, well worn and almost falling apart. The box has been sitting on a shelf in my office for the past couple of years — a room that expresses a modern, cosmopolitan idea of taste that formed almost in opposition to the ornate and cobbled-together rooms of my upbringing. Recently, I’ve found myself fixated on this box, as though it can reconnect me with the warmth of childhood memories and reconcile my discomfort with a binary sense of self. Coincidentally, the box is locked and does not have a key.

NANU AL-HAMAD

Designer and co-founder of the art collective GCC, Brooklyn and Kuwait, USA.

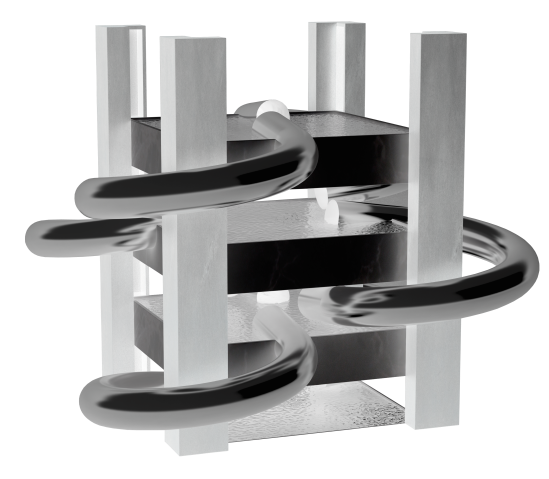

Nanu Al-Hamad of Al-Hamad Design, Enabler (Structure-Activity Relationships), 2015. Photo: Bek Andersen.

The paradox of comfort hides in the fact that we must define comfort while prioritizing it. Comfort is unstable, varying between each individual nervous system. A gentleman once said, ‘As a furniture designer, I rarely sit; discomfort is terribly motivating.’ It was his method to inspire desire, it made him care. He imagined throwing a chef onto a desert island for days just to see the next meal he would prepare. These daydreams steam out of discomfort. However, he had continued this practice for so long, he lost his sense for what ‘comfort’ was. Comfort became being uncomfortable. His furniture designs began to place users into a position of their very own disliking, and to hope (ceremoniously) that they would eventually permit themselves to find comfort within it. We make things to help people, but never allow people to help things. Carrying a bioluminescent sea crab with great care in an attempt to save its life, fixing a flat tire in a snowstorm, washing your father’s deceased body, and building his tomb with your own young hands. How terribly distressing these actions are, but then relief sets in. Comfort is the greatest disappointment that has ever existed. It doesn’t enable perspective. Anguish forces your way into awareness. One day, this gentleman saw a little girl in a wheelchair. The girl looked up at the Enabler. She transferred herself onto it. Slowly pulling the hydraulic shaft, she lifted herself up higher and higher, perspiring. Then she began to swing. Truly all on her own. This journey was a course of pain, but it ended up in swinging bliss. The girl thought to herself, ‘Even though comfort is a reality, its effects are temporary.’ Alleviation is very much about enjoying a situation’s malaise. This gentleman suggests we support our efforts in attaining discomfort.

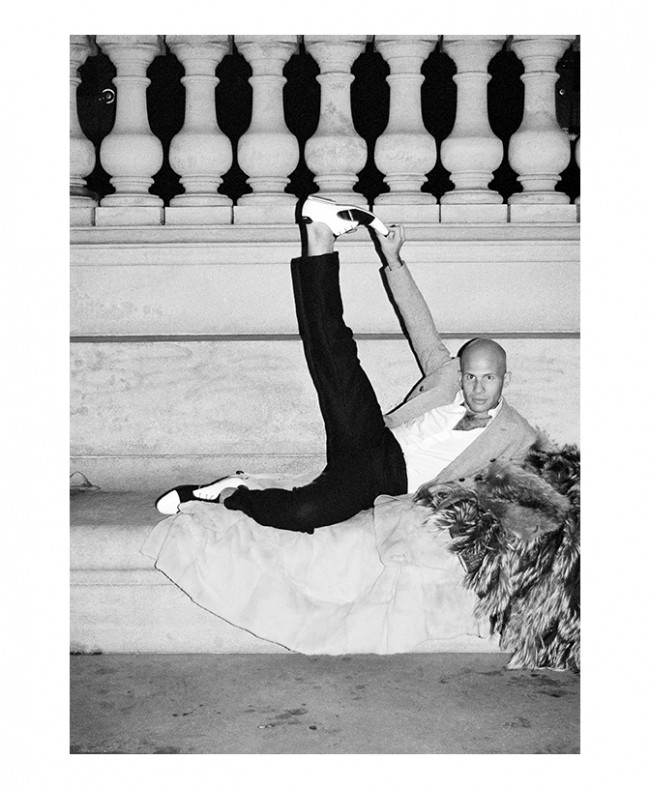

RAFAEL DE CÁRDENAS

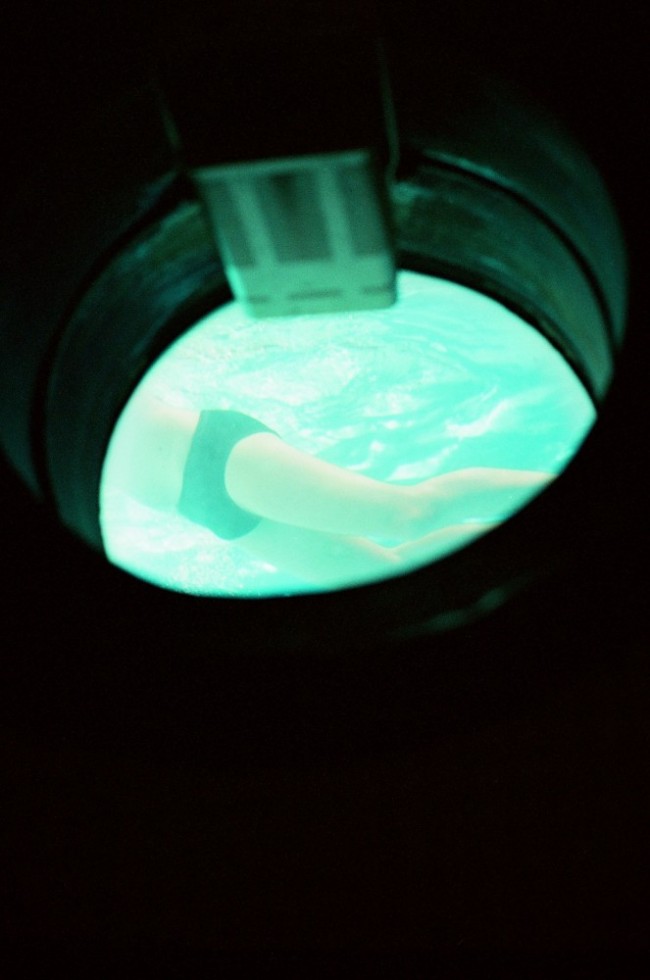

Designer and founder of Architecture at Large, New York City, USA

© Rafael de Cárdenas / Architecture at Large.

A good slide, particularly a good waterslide, is a kaleidoscope of comfort and discomfort. It cradles you, cools you off, and makes the force of gravity viscerally felt. It drags you, twisting and turning, through an eye of falling water, into the open-ended luxuriance of the pool. It offers an endlessly repeatable cycle of full-bodied suspense and full-bodied tranquility. Water, air, you, tumble over each other, collide and mix. Rinse, repeat. This design prolongs that cycle by breaking down the slide-pool binary somewhat, in order to heighten the ambiguous states of (dis)comfort that a good slide offers. A labyrinthine, cascading structure, in which slides and pools alternate as isolated and isolating spaces, draws out the typical state of bodily suspense and renders it atmospheric. Rather than a confined space leading into a relatively unrestricted one, here the only truly unrestricted space sits at the apex, with all the suspense of the descent lying before you. And the slide itself becomes open-ended by being unraveled into a multiplicity, with double openings at each level. Ordinarily, the variables of using a waterslide are limited to time spent on the slide versus time spent in the pool. But the variables here are numerous, and the way someone might engage with this structure is deliberately ambiguous. Uncertainty can be terrifying.

Introduction by Drew Zeiba.

Taken from PIN–UP 23, Fall Winter 2017/18.