WAKE UP CALL: Architectural Comfort in the Age of Passivity

Image via IStock.

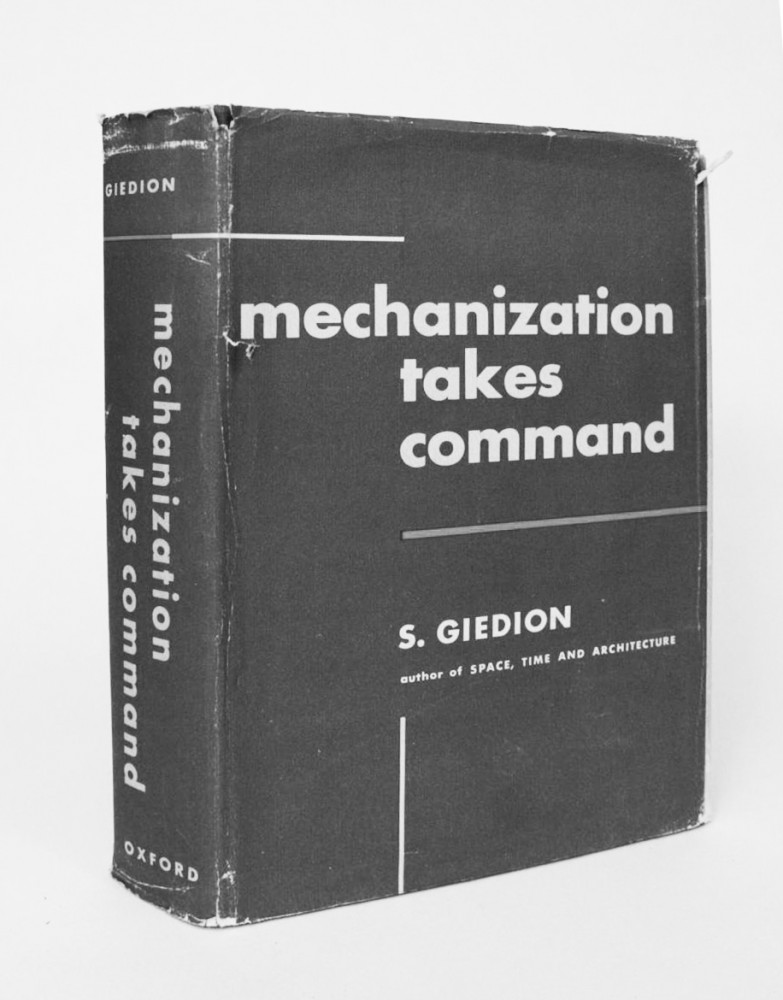

Comfort is a tricky concept. Commonly understood as a positive value, it is a double-edged sword. In his 1948 treatise Mechanization Takes Command, Sigfried Giedion reminds us that the word comfort, in its Latin origin, meant “to strengthen.” It was only after the 18th century, in Western culture, that comfort became identified with “convenience,” he explains. Since then, in architecture, comfort is normally related to bodily experience in terms of sensory relaxation. Generally presented as an objective parameter, comfort refers to a physical state rather than a psychological mode. It is differentiated from wellbeing or happiness as, initially, it does not operate at a mental level, although it might have later consequences upon the mental. Comfort is achieved in an atmosphere where material conditions allow the body to repose. The air, the lighting, the sound, the smell, and the solid elements provide relaxation and avoid pain. In a space that is considered comfortable, activity can be pursued with the minimum effort.

Man shall order and control his intimate surroundings so that they may yield him the utmost ease. This view would have us fashion our furniture, choose our carpets, contrive our lighting, and use all the technical aids that mechanization makes available. — Sigfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command (1948)

Sigfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command, 1948.

Since the invention of the modern sofa for the French aristocracy, infinite means of comfort have been introduced into everyday living spaces. With the Industrial Revolution, sophisticated machines, like the escalator or air conditioning, became indispensable in our buildings. The emergence of the digital age brought advanced devices to adjust the qualities of our environment and optimize the use of the city; from domotic systems to geo-localized mobile applications, architecture has undergone profound transformations due to new technologies. Spatial programs and spaces themselves are continuously adapting and being drastically altered according to the requirements of techno-comfort, whether it’s the simple alcove and fireplace that were replaced by central heating, or the neighborhood bar that is rendered obsolete by online-dating apps like Tinder.

With the advent of the 20th century, Modern architecture made techno-comfort a political battle: the Existenzminimum became a central theme. Spatial standards of comfort for the house were developed along with a vision of a functional and productive city. In 1936, Ernst Neufert published Architects’ Data, a guide to architectural design that provides spatial requirements, with specific dimensions, to comfortably accommodate the body in space. Since its first edition it has been translated into 17 languages and re-edited on uncountable occasions. In parallel to Neufert’s polite recommendations on how to optimize our living spaces came impositions: to guarantee minimums of comfort — and also maximum control — public and private spaces have been strongly regulated by legal institutions. This tendency came with the emergence of the nation state, and has achieved, today, the highest level of intervention in the built environment: the volume of rooms, the dimensions of openings, the articulation of programs and the properties of materials are some of the parameters that are regulated by law and by increasingly rigorous building codes.

But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness, I want sin. — Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (1932)

Through the voice of one of his characters, British “acid” novelist and social critic Aldous Huxley warned of the dangers of a society of comfort. He was not the only one. Thinkers like Herbert Marcuse also warned that legal imposition and implementation of a material culture of comfort would bring social and political passivity. Embracing comfort was seen as accepting a hegemonic power that provides everyday ease in order to manipulate, in return, all aspects of our lives. Marcuse, who believed the erotic dimension of the body had an emancipatory role, clearly differentiated comfort from pleasure. Comfort differs from pleasure as the latter may imply demanding and tiresome bodily activation. Pleasure awakes new understandings of reality, while comfort numbs us.

I think we are faced with a novel situation in history, because today we have to be liberated from a relatively well functioning, rich, powerful society. — Herbert Marcuse, Liberation from the Affluent Society (lecture, 1967)

An uncomfortable space can be a pleasurable space. An uncomfortable space can be a space of consciousness. In a 2016 article in El Estado Mental magazine, Paul B. Preciado describes his experience of inhabiting a completely empty house in Greece.

My hips crush against the wood at night and I wake up stiff. Nevertheless, it is an inaugural experience, an aesthetic experience: one body, one space. — Paul B. Preciado, Casa vacía (2016)

In the emptiness of the house, there was no comfort. Preciado describes how techno-bourgeois conventions were suspended. All physical and digital technologies developed with the aim of bodily ease provide fixed and standardized spatial and symbolic relationships. Techno-comfort machinery is the catalyst of fixed social and political structures. From Preciado’s point of view, a lamp next to a bed is a marriage of convenience.

Ikea is for the art of inhabiting what heterosexual normativity is for the desiring body. — Paul B. Preciado, Casa vacía (2016)

A well-sized flat with one double room and two single rooms is a machine for the perpetuation of the social norm. A constantly well-illuminated space is a machine for the reproduction of the liberal economy. A well-insulated wall is the fear of the other. But a steep stair is an achievement, a cold flat a reminder of your limits, and a too-small room the perfect place to become lovers.

Discomfort is a weapon.

Text by Pol Esteve. Derived from a course Esteve taught at the Architectural Association in London.

Taken from PIN–UP No. 23, Fall Winter 2017/18. Image via iStock Photo.