TOTAL SPACE: A Disorienting Exhibition For Disorienting Times

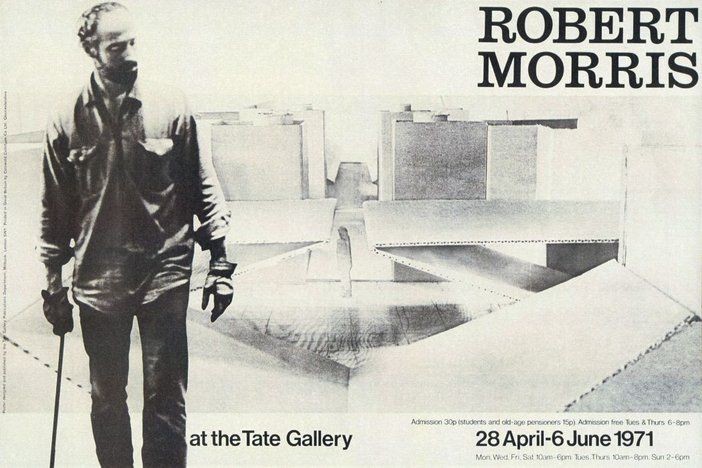

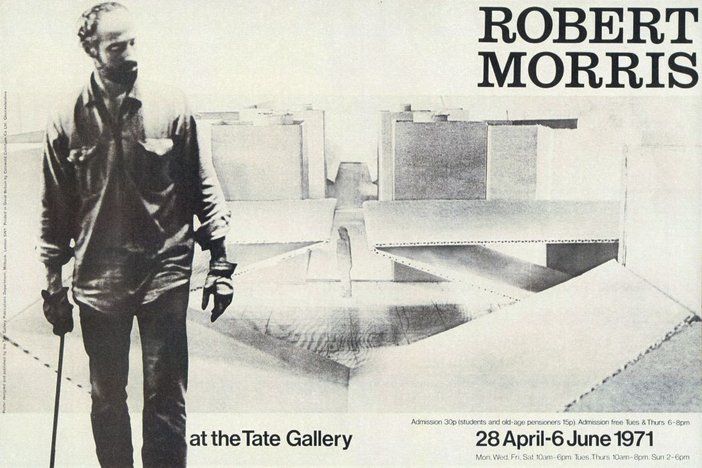

In 1971, the American conceptual artist Robert Morris mounted Bodyspacemotionthings, a solo exhibition at Tate Britain in London. While the English institution thought it was getting a retrospective, Morris had other plans: the museum’s grand sculpture hall would become a raucous site for sensory exploration. Some 2,500 visitors stormed the exhibition’s playground of geometric objects, balancing atop inflatable white balls, lugging bricks across plywood ramps, and spinning themselves sick inside concrete cylinders. Here, boundaries between subject and object, object and environment, and individual and collective experience became porous and sticky, as the gilded architecture of the museum cracked under the ecstasy of play (several of the museum’s other exhibitions were reportedly damaged in the pandemonium). Ordered to shut after four short days, the show nonetheless went down as one of the most transgressive exhibitions of the 20th century.

-

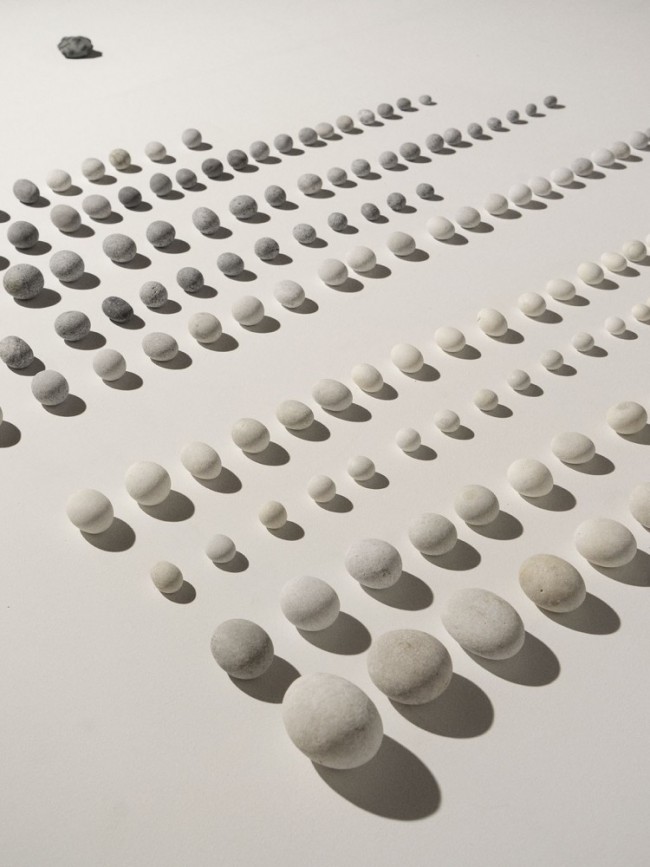

Robert Morris, Bodyspacemotionthings exhibited at the Tate Gallery, 28 April – 7 May 1971. Image courtesy Tate Archive.

-

Exhibition poster for Robert Morris, Bodyspacemotionthings. Image courtesy Tate Archive.

This desire to rupture the social hierarchies of space and create new kinds of knowledge through sensory encounter was nothing new. (Before Morris came writers like Italo Calvino, Jorge Luis Borges, and Vladimir Nabokov, whose multi-sensory, multidimensional work can be thought of as analog hypertext fiction; back in the white cube, radical movements like Gutai, expanded cinema, and Fluxus were poking holes in institutional spaces since the 1950s.) Yet Bodyspacemotionthings got at a gnawing hunger for a totalized experience of space that dials up the intensity and agency of embodiment. Fifty years on, Total Space, curated by Damian Fopp and Matylda Krzykowski at the Museum für Gestaltung in Zürich, addresses that same desire — this time, with the added complexity of digital space.

“Total Space is a proposition as much as an exhibition,” suggests Krzykowski. “It’s a call to break the mold of (design) exhibition making: away from the white cube, the historical viewer-subject relation, and the labels, in order to create experiences that are inviting, illuminating, and active.”

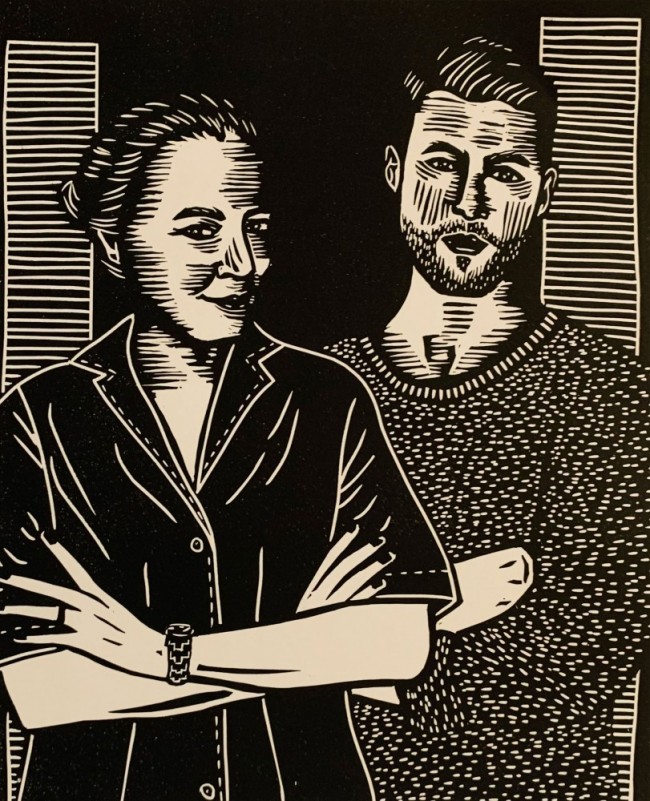

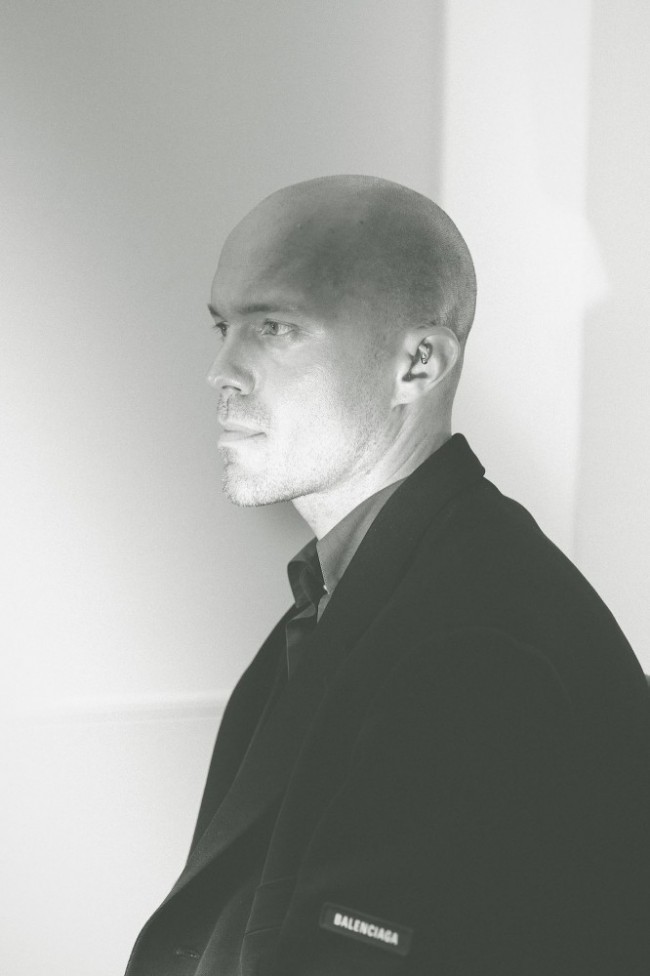

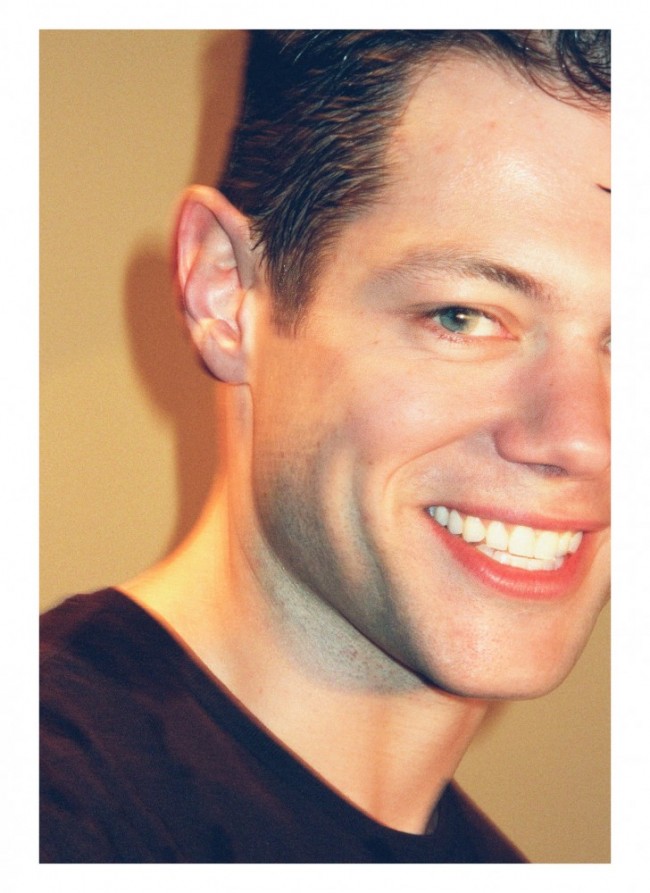

Serenity TV featuring Matylda Krzykowski (right) and Damian Fopp (left), curators of Total Space for Museum für Gestaltung Zürich. (Video produced by Tristesse)

Fopp and Krzykowski selected five international design studios — Trix and Robert Haussmann, Soft Baroque, Kueng Caputo, Luftwerk, and Sucuk & Bratwurst — to create their own version of a “total space” in a sequence of rooms that radiate outwards from a rotunda-like exhibition core. An intergenerational mix was crucial to the show — the groups are in their 20s to 80s — as was a collaborative approach to design that heightens sensory experience. These installations were conceived to provoke, hypnotize, disorient, and delight visitors in equal measure.

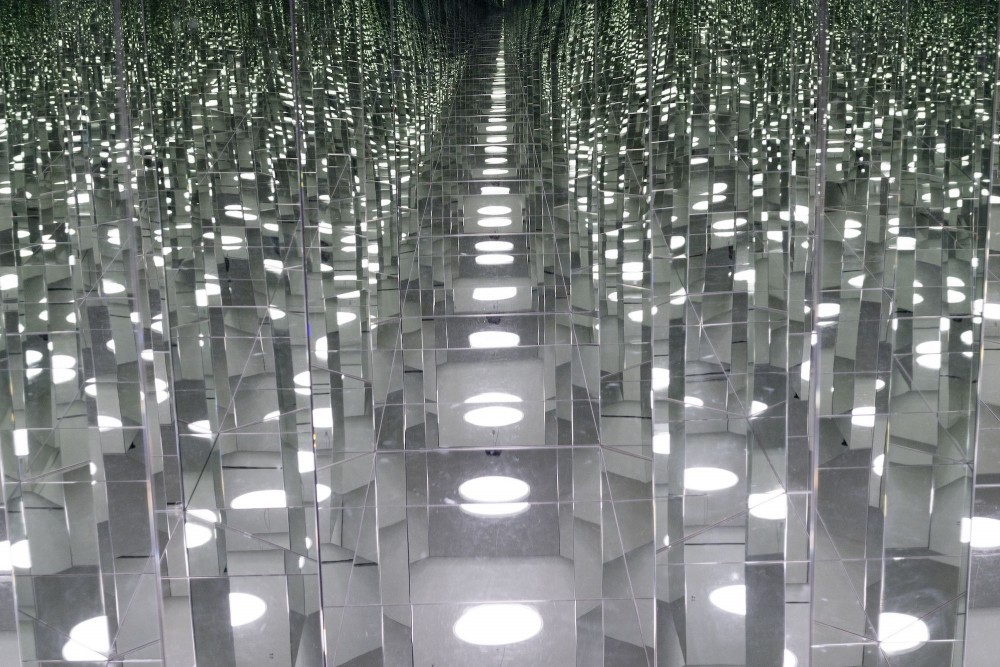

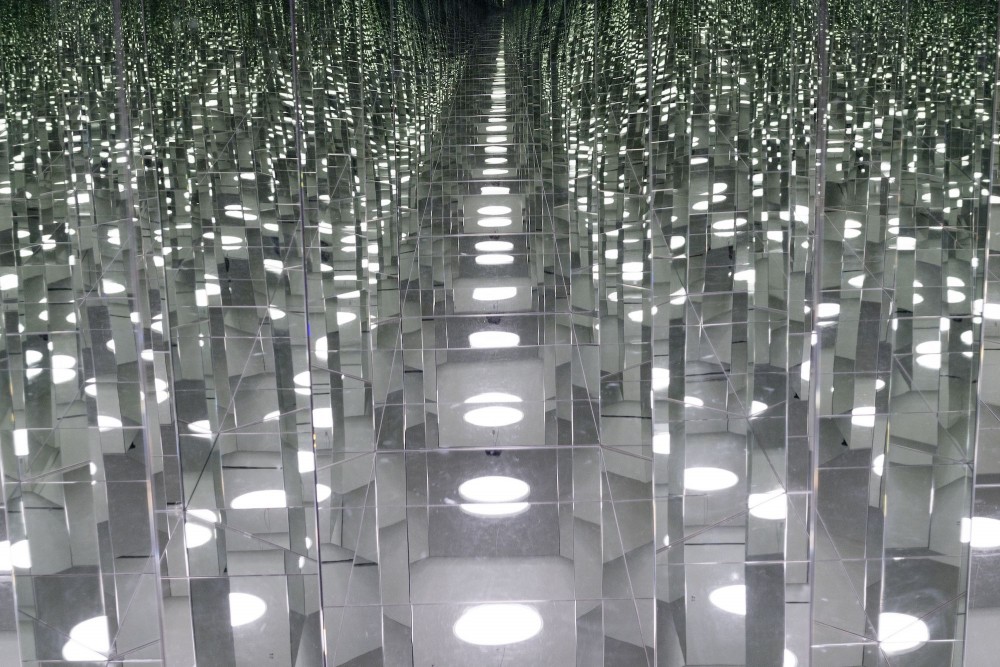

In Trix and Robert Haussmann’s Octagon room, the architect and designer duo play with mirrors: floor-to-ceiling reflective cabinets create an infinity room of right angles with no discernible beginning or end. A mirrored door leading into the space is kept ajar like a portal to an alternate dimension. Thinking about the illusory environment of mirrors as a kind of analog virtual space, Haussmann’s total space is the inverse of Sucuk & Bratwurst’s installation, Once Upon a Time There was a Ladybug, which was conceived digitally before being materialized in physical space.

-

Trix & Robert Haussmann’s mirrored installation designed for Total Space curated by Damian Fopp and Matylda Krzykowski at the Museum für Gestaltung in Zurich. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Octagon, an installation designed by Trix & Robert Haussmann for Total Space. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Trix & Robert Haussmann designed Octagon, a mirrored infinity room. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

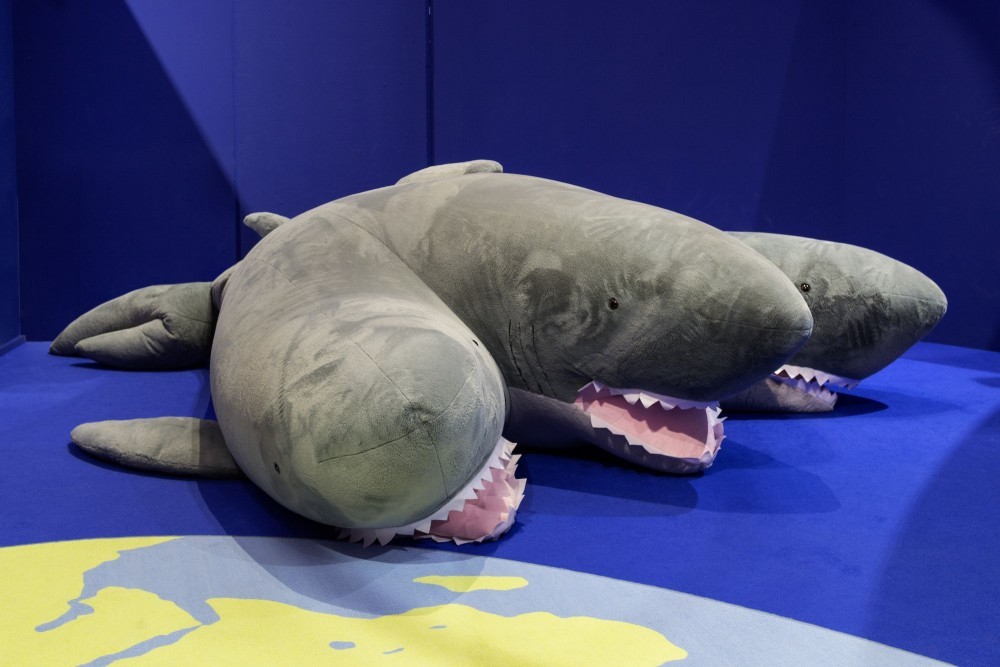

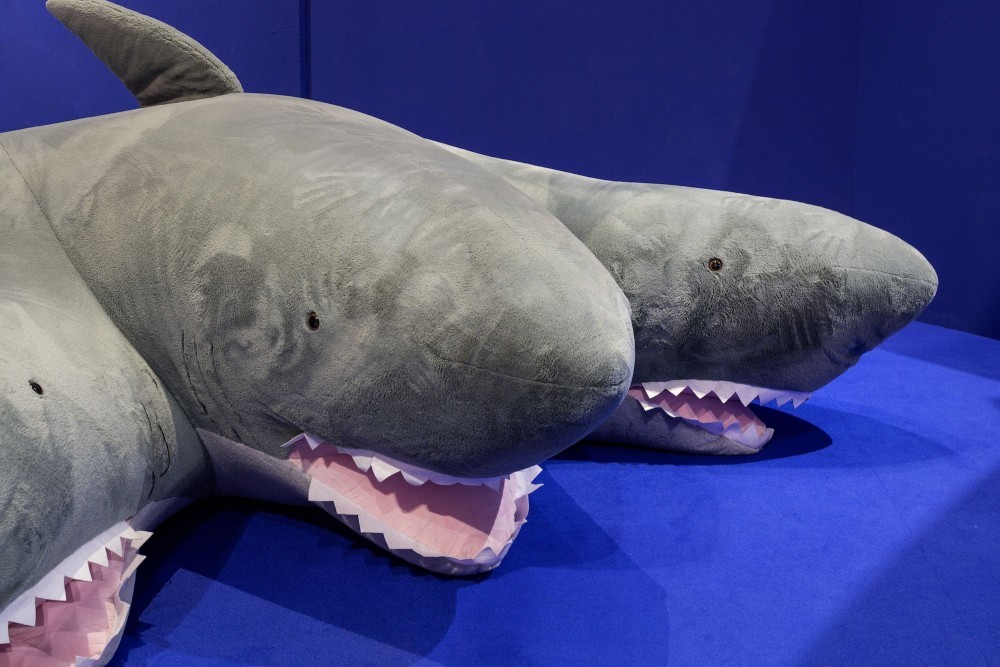

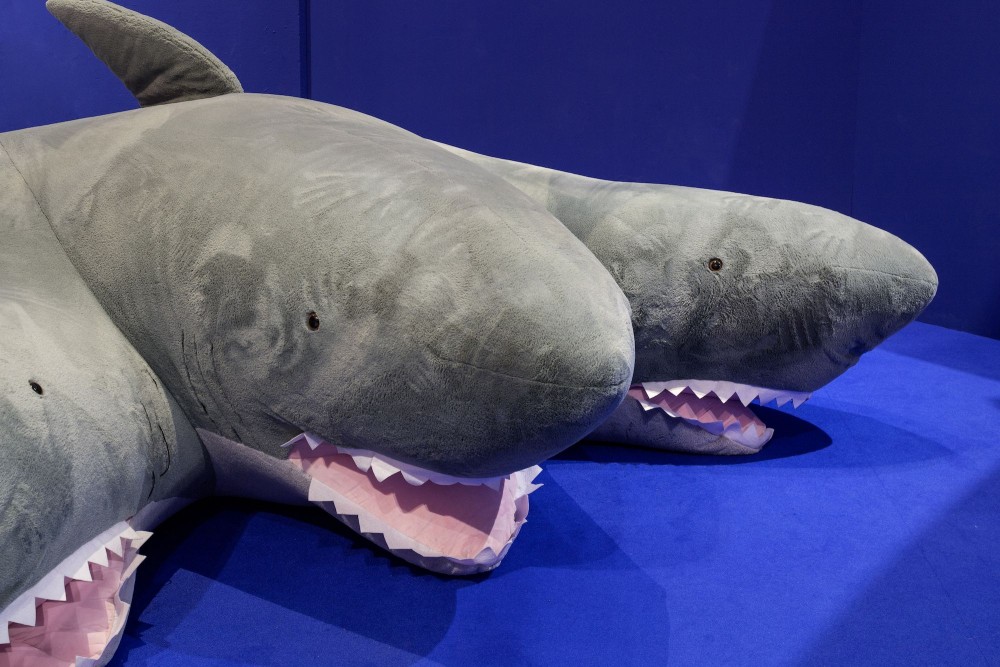

Populating their cobalt-washed room are a variety of 3D-rendered fantastical creatures transformed into XXL plushies, including a three-headed shark, five-headed swan, and a two-faced Frankensteined giraffe. These critters are citizens of an Anthropocene nursery: beneath them lies a rug shaped like the Earth split in two, while above, a baby mobile modeled on the EU flag whizzes erratically. Tension builds beneath the cuteness. “We wanted to reflect on the bitter, heartbreaking transformations of our planet,” suggests the collective, “While creating a space of total nostalgia, a safe place to play again.”

-

XXL plushies populate Sucuk & Bratwurst’s installation, Once Upon a Time There was a Ladybug. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Sucuk & Bratwurst’s installation Once Upon a Time There was a Ladybug evoked an anthropocene nursery. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

An XXL flamingo plushie, part of Sucuk & Bratwurst’s installation for Total Space. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Plushies and an EU-themed mobile in the nursery themed installation by Sucuk & Bratwurst. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

A three-headed shark plushie in Sucuk & Bratwurst’s installation for Total Space. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

A three-headed shark plushie in Sucuk & Bratwurst’s installation for Total Space. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

A five-headed swan is one of the plushies, first conceived as a 3D-rendered creature for Sucuk & Bratwurst’s cobalt-blue installation. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

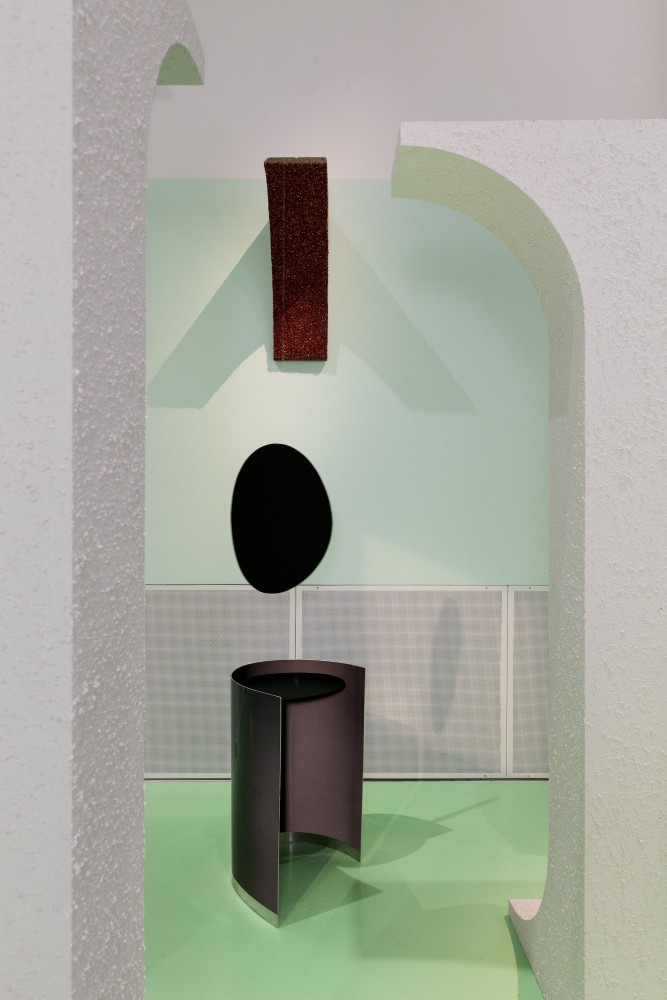

Sneaking through a tunnel clad in acoustic paneling lands you in the pastel utopia of Kueng Caputo. Titled Cosa Pensi? (Italian for “what do you think?”), the installation is a forest of columns made from an assortment of materials including pigmented sand, cinder blocks, travertine, and LED tube lighting. Designed to challenge the visitor’s sense of scale and stimulate the senses through a layering of materials that are not what they seem, Kueng Caputo’s space is one of provocation and play.

-

Cosa Pensi?, an installation by Kueng & Caputo designed for Total Space. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Cosa Pensi?, an installation by Kueng & Caputo designed for Total Space. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Kueng & Caputo’s pastel utopia leads into a light installation by Luftwerk. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

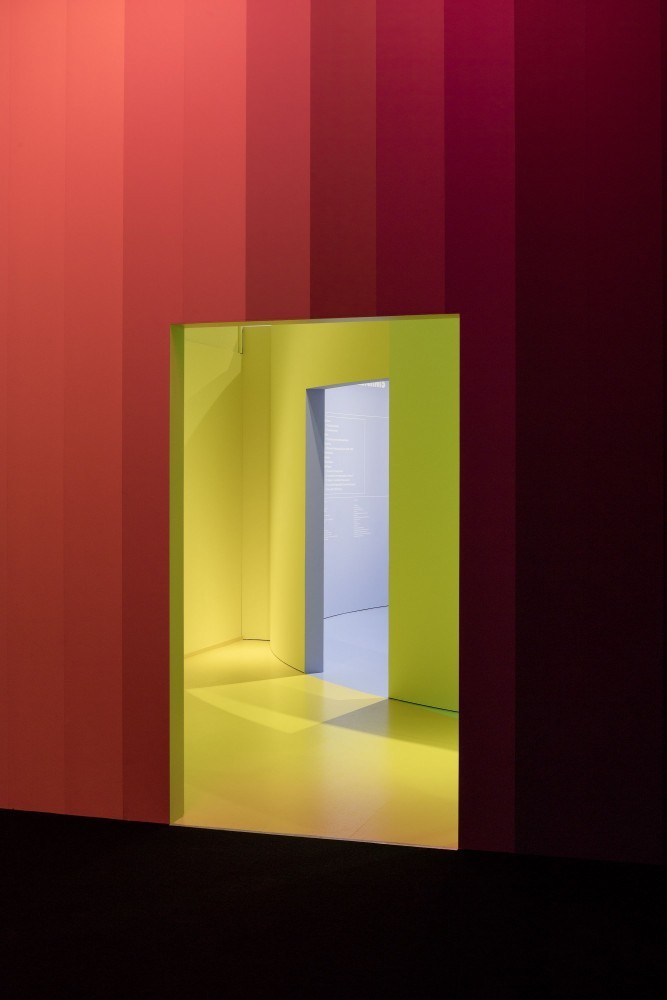

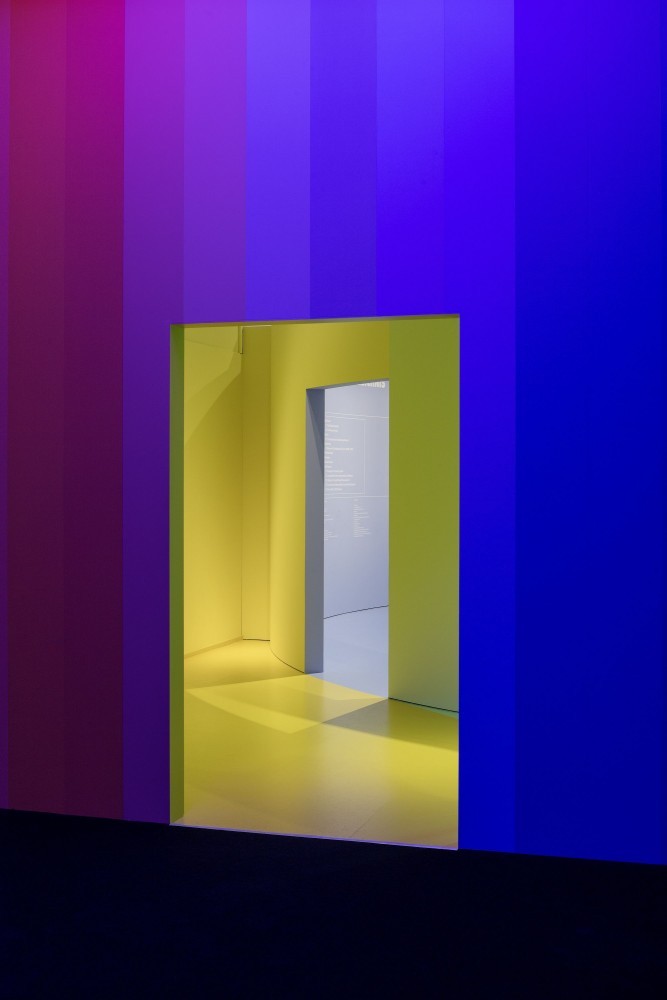

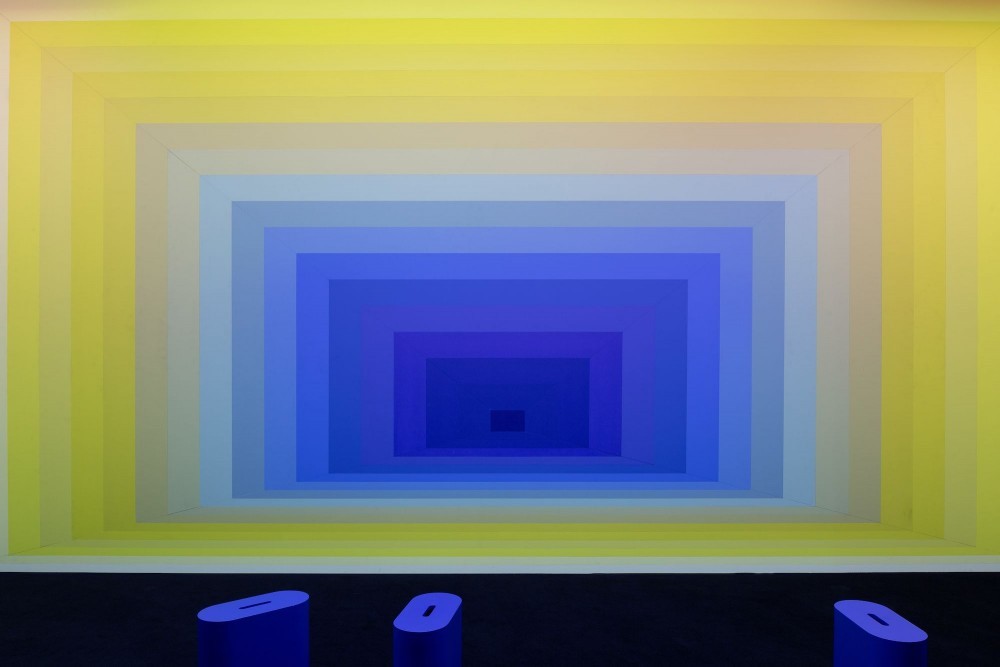

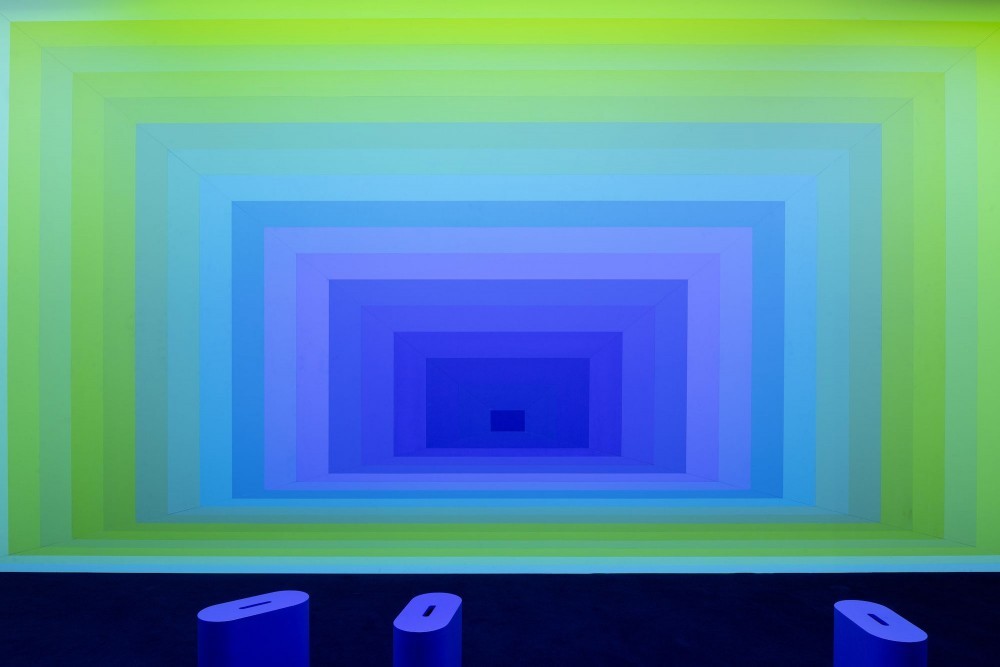

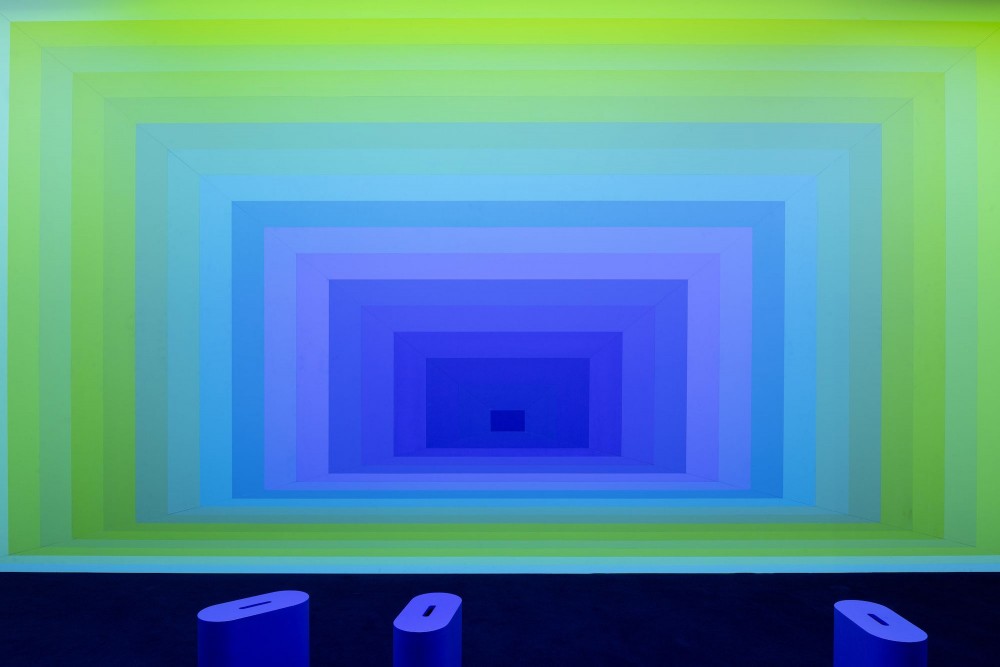

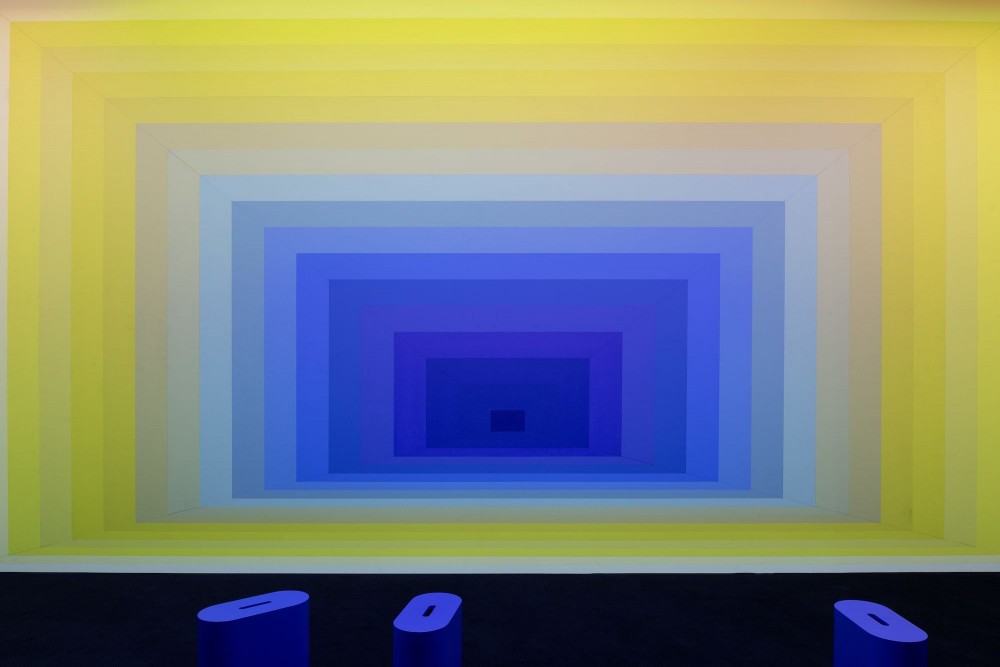

The forest leads into Landscape is a Composition, a light art installation by Luftwerk that riffs on Renaissance man Leon Battista Alberti’s musings on color and experience. Hallucinogenic gradient light projections bifurcate the room, distorting the user’s sense of space. This is the most ocularcentric room in Total Space, reducing the presence of the body beneath a strobe-like neon glow.

-

Landscape is a Composition, a light art installation by Luftwerk. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Landscape is a Composition, a light art installation by Luftwerk. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Landscape is a Composition, a light art installation by Luftwerk. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Landscape is a Composition, a light art installation by Luftwerk. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Landscape is a Composition, a light art installation by Luftwerk. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

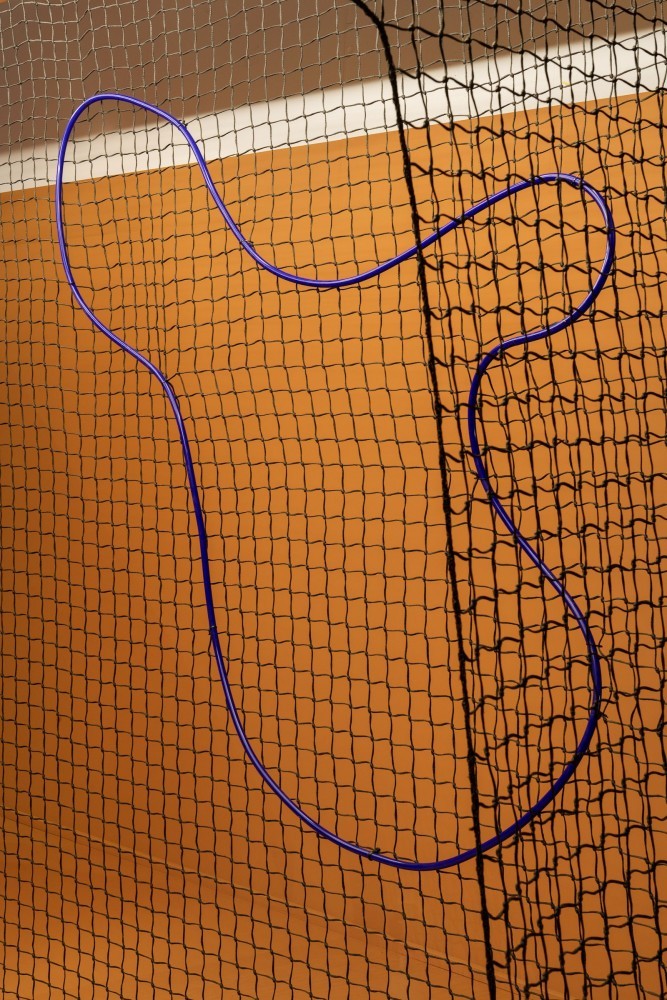

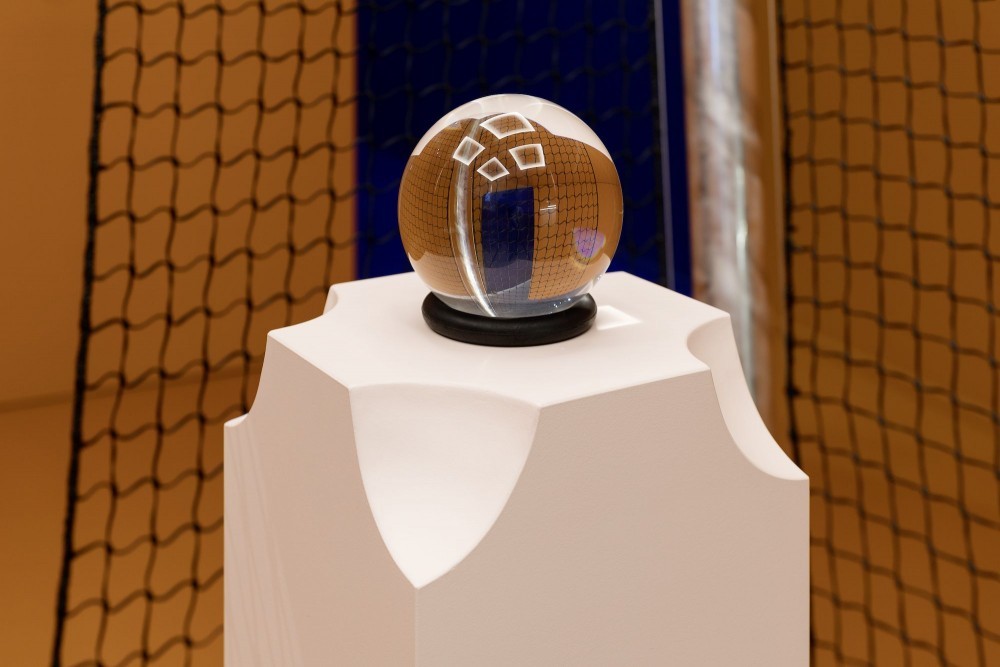

In hard contrast is Soft Baroque’s Dance Mix. Conceived as an alternate universe to the traditional gallery space, the duo’s pavilion is composed of a gyrating mock white cube made from transparent nets. Inside, visitors can take a seat on a Cracker Barrel-aesthetic wooden chair as the walls dance around them, or peruse a fantastical furniture catalog printed on a white tablecloth. Nearby, a snow-globe inscribed with the word “placeholder” sits atop a scalloped pedestal with bites taken out of it. Sporty orange walls and LED overheads morphed into stadium-style floodlights dial up this discombobulating spatial experience; as the mesh cage stutters and jerks around you, a wrestling match feels inexplicably near. “Dance Mix is a funny surreal jab at modernist style and the way it's become a very decorative thing,” shares Nicholas Gardner, who runs Soft Baroque together with Saša Štucin. “But it’s also a serious proposal for an alternative gallery infrastructure.”

-

Soft Baroque’s installation Dance Mix is one of five visions of a “total space” included in the exhibition. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

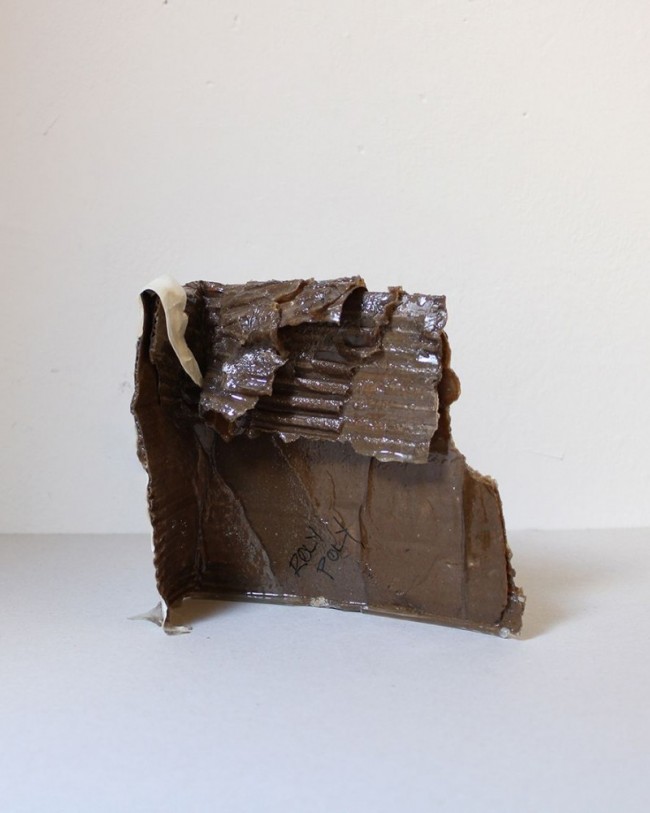

A snow-globe atop a scalloped pedestal with bites taken out of it in Soft Baroque’s installation. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Detail of a snow-globe inscribed with the word “placeholder” in Soft Baroque’s installation for Total Space. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

The exhibition design of Total Space (also by Fopp and Krzykowski) borrows from familiar tokens of digital space: pervading the installation is Pantone’s Serenity Blue, a peculiar RGB mash-up that fundamentally exists online. (“It’s a very weird abstract blue on the border of purple; all the folders on your desktop are that color,” explains Krzykowski.) Visitors are guided through the sensory emporium by the intrepid pointer cursor: a beloved relic of early 90s Internet wayfinding. A cross between Mickey Mouse’s chubby mitts and the clinical post-Covid handshake, the gloved hand inevitably conjures a different association today. Information on the artists and the Total Space manifesto appear in a Wikipedia-style layout at the exhibition’s core — which is in itself a portal, a non-linear funhouse with doors leading to all the total spaces. “Why do we believe that text must appear at the entrance to a show?” ponders Krzykowski. “What other types of experience are available if you first encounter the exhibition with your body, not with your eyes?”

-

Information on the artists and the Total Space manifesto appear in a Wikipedia-style layout at the exhibition's core. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Wall texts for the exhibition are consolidated on the serenity-blue walls of the rotunda-like exhibition core. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

On screens the curators included contributions from two dozen architects, designers, curators, and scenographers, offering their own example of a total space. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

The exhibition asks the audience to offer their own ideas of what a total space is. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

-

Total Space includes a portion titled Total Info, including wall texts, screens with commentary on the theme, and the chance for the audience to add their ideas. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

As method, total spaces move fluidly between architecture and art, blurring interior and exterior space and complicating corporeality: think of the atmospheric architecture of Diller Scofidio + Renfro's cloud-like Blur Building, to Niki de Saint Phalle’s cosmogenic Tarot Garden, to the Reversible Destiny Foundation's topsy-turvy domiciles. It fundamentally involves a type of world-building, is often collaboratively conceived, and it drips with affect. But most of all, total spaces are slippery: everyone has their own idea of what they are. Acknowledging this inherent subjectivity, Fopp and Krzykowski called upon two dozen architects, designers, curators, and scenographers to offer their own example of a total space. Ranging from 1960s museum shows to British nightclubs and artificial tropical islands, the heterogeneous mix finds its way into the exhibition through a series of screens — the same way most of us will experience the show mid-pandemic.

-

View of Variation On A Basic Item: Bread, MAN transFORMS. Aspects of Design, curated by Hans Hollein and Lisa Taylor, Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York, 1976. © Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

-

The entrance to Kueng & Caputo’s installation titled Cosa Pensi? is a tunnel clad in acoustic paneling. The gloved hand cursor pointer on the screen is a beloved relic of 1990s wayfinding. Photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.

Alongside Morris’s Tate heist, the curators of Total Space cite Hans Hollein and Lisa Taylor’s 1976 show MAN transFORMS at the Cooper-Hewitt as a key reference. Hollein and Taylor’s exhibition deconstructed the museum space and allowed visitors to build their own total environment in its place. Across history, the desire for total space emerges from and is catalyzed by periods of global instability and cultural stasis. It’s a rush toward a new kind of feeling and a new kind of space; a reassertion of embodied knowledge when everything else is so uncertain. While the pandemic constricts our ability to move through the world with all our senses, Total Space becomes an increasingly urgent design premise for life after lockdown.

(Serenity TV - Video for Total Space)(https://vimeo.com/488193188) from (MATYLDA KRZYKOWSKI)(https://vimeo.com/matylda) on (Vimeo)(https://vimeo.com).Text by Alice Bucknell.

Installation photography courtesy Pierre Kellenberger ZHdK.