AROUND THE PROTEAN TABLE: From Judy Chicago to changing notions of Digital Era Connection

To live together in the world means essentially that a world of things is between those who have it in common, as a table is located between those who sit around it; the world, like every in-between, relates and separates men at the same time.

— Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition

The table appears and reappears a total of 17 times in this — Arendt’s exposure of humanity and its flaws in a long, unravelling polemic. The comparison of the table with the world is a good one. For not only does the table signify humanity’s shared space — an in-between, a centering — but it too bears our marks. Worn edges, fingerprints, burns, grooves and holes; an unsteady leg. These are the impressions we make, fueled by greed, or a need or desire.

By table I mean the post-industrial table of the home, positionally contingent but often located in the kitchen. Not the desk — that solitude — for it comes with its own limitations, nor the antiquity of the dining table, but the table as a protean notion. By protean, I mean a looseness, a tendency to change; the ability to do many different things. I mean, adaptability –– a table as office, accidental canvas, cut-and-stick page — and shifting in meaning. I mean all the qualities of the table — its gravity, its capacity to gather us, its generosity — without the solid base. Or rather, the base exists, it just looks different now. It is unsteady — this table — but it is open. A table that suits this space we’re in, with its shifting social practices and domestic rituals, themselves a consequence of technology, displacement, borders.

It’s hard to push over something with four legs. Try.

Chess table. Photography by Alan Mak. Courtesy Wikipedia.

My father used to deal in large wooden things from far away places and now, at 74, deals in smaller things from nearby. Though recently he had to deliver a table that was too big for the boot of his dirty station wagon. So he fixed it to the roof with dogged ties, near defunct now. He emanated pleasure at the task as he spoke of it. And the sun was so low — that winter-kind-of-low — that it cast the table’s shadow onto the road below the driver’s window and my father watched the table’s cut black version of a form as he drove in that orange sun. He smiled the whole way, as if he were in the company of an old friend on a long journey.

Even upside down, a table is a table.

It is also a fixture, a fixative, a moment of communion between people, forced or needing. It is a meeting place, a site of nourishment. It is ceremonial and social. Temporary — in its durational acts — and permanent — in its place. It calls the feast and whispers famine. The table is duplicitous. that is to say it is also a reeking void, site of gluttony, a trap. A domestic burden too often governed by structures of authority — that of prayer or husband.

For some cultures the table has never existed, though people still gather, with a space between them, laden with edibles or burning with fire, which means much the same thing.

And now, the table is classroom, office, studio, for a displaced or replaced human population. I say replaced because the rhetoric is insisting, with some truth, that this global pandemic on a scale that none of us have witnessed before is also a kind of return. A reappraisal of the world and our place in it. And as we return to the table — in this temporal liminal space, in our moderated formations of togetherness — or simply alone — we are bound and apart.

Delbert Mann's film Separate Tables (1958). Courtesy The Movie Database.

The table is all of these things and none of these things and at a distance it gains and loses meaning. We may return to its values, but the means by which we reach them look vastly different — COVID-19-enforced-isolation-accelerated technology, and our capacities to connect at a distance. But this oscillation between solid material, and protean notion, is itself indicative of our transient collective state.

So how might we use it to think through and shape creative practice?

The table has always been generative. Once that meant forms of domesticity and labor and was suffocating on those same terms. Women served the table, though possession was a different matter. Then tentatively, around it, they began to stitch stories into quilts and share them out loud, in oral tradition. Through such acts of togetherness, women made their mark, proffered new perspectives, shared knowledge and offered counsel.

These functions still stand.

A solid table binds us so that we can do the “thinking business” Arendt spoke of, together, in friendship and labor. A table makes an evening, a breakfast. Give me a table over a sofa or armchair. I don’t want to be reclining. I want to sit upright, present, talking to you now, with something solid beneath my glass.

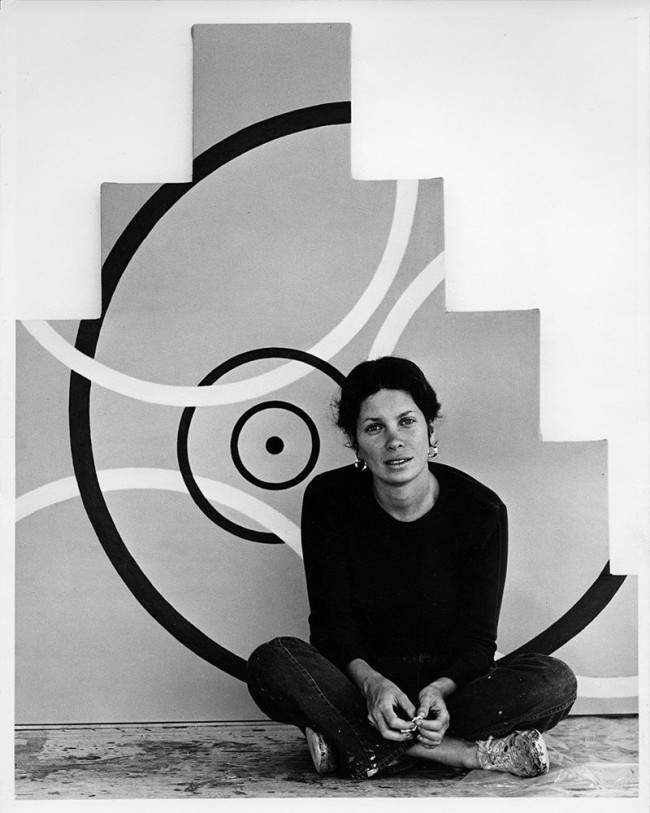

Judy Chicago's Thursday Night Potluck with “The Dinner Party” Workers (1978). Courtesy Brooklyn Museum and Through the Flower Archive.

The public realm, as the common world, gathers us together and yet prevents our falling over each other, so to speak. What makes mass society so difficult to bear is not the number of people involved, or at least not primarily, but the fact that the world between them has lost its power to gather them together, to relate and to separate them.

— Arendt

Arendt was skeptical about gathering. Its abuse for economic benefit. She felt the modern world was neither participating in the public active realm or private, domestic one, rather sinking into the social realm — one devoted to mass production and consumption where we each lose definition, and with it, our voice.

She lacks my peaked optimism. Or is it renewed optimism?

Even before this slow dissolution of formal dining tables and cut-glass gender roles, the table became form and site of protest. We see it in the generative nature of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, the reflective state of Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook and Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, for whom table is stage and altar. The table became powerful in its conflation of the political with the personal. A common ground.

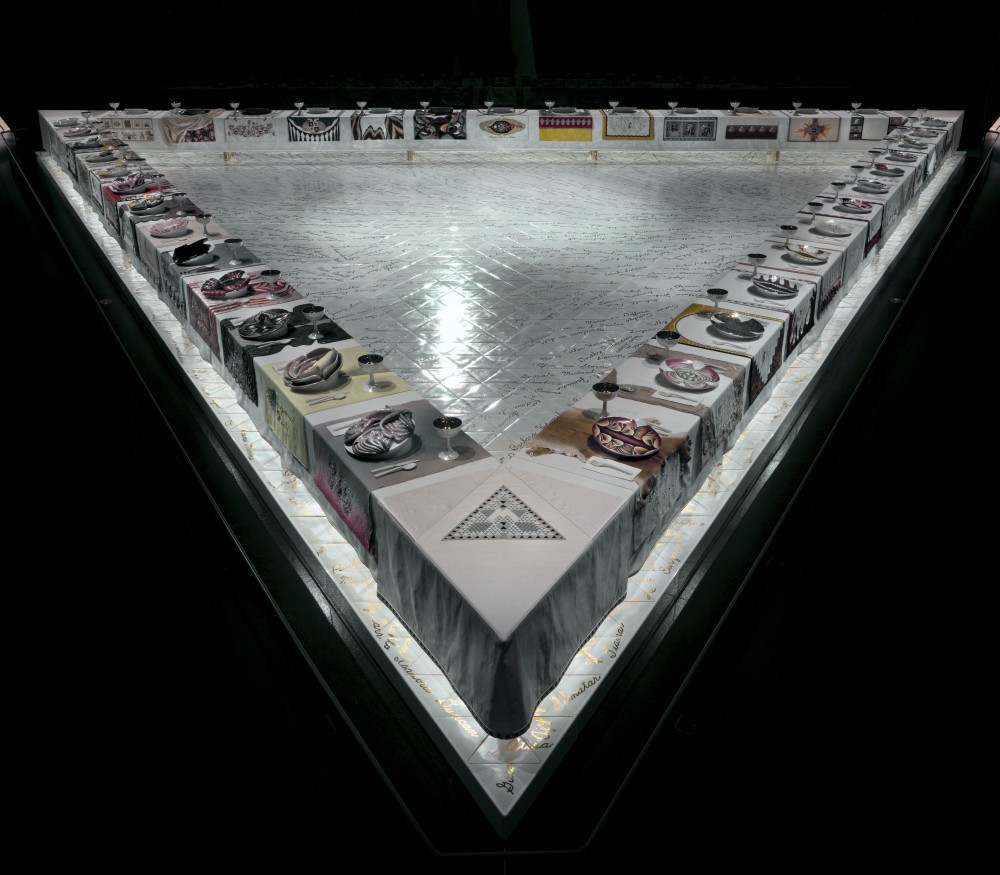

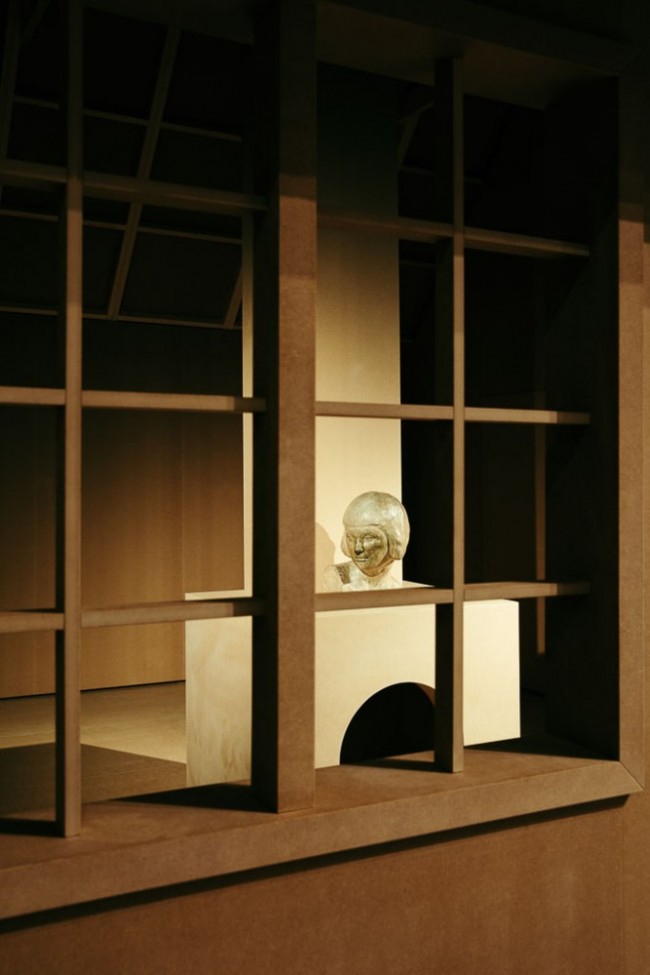

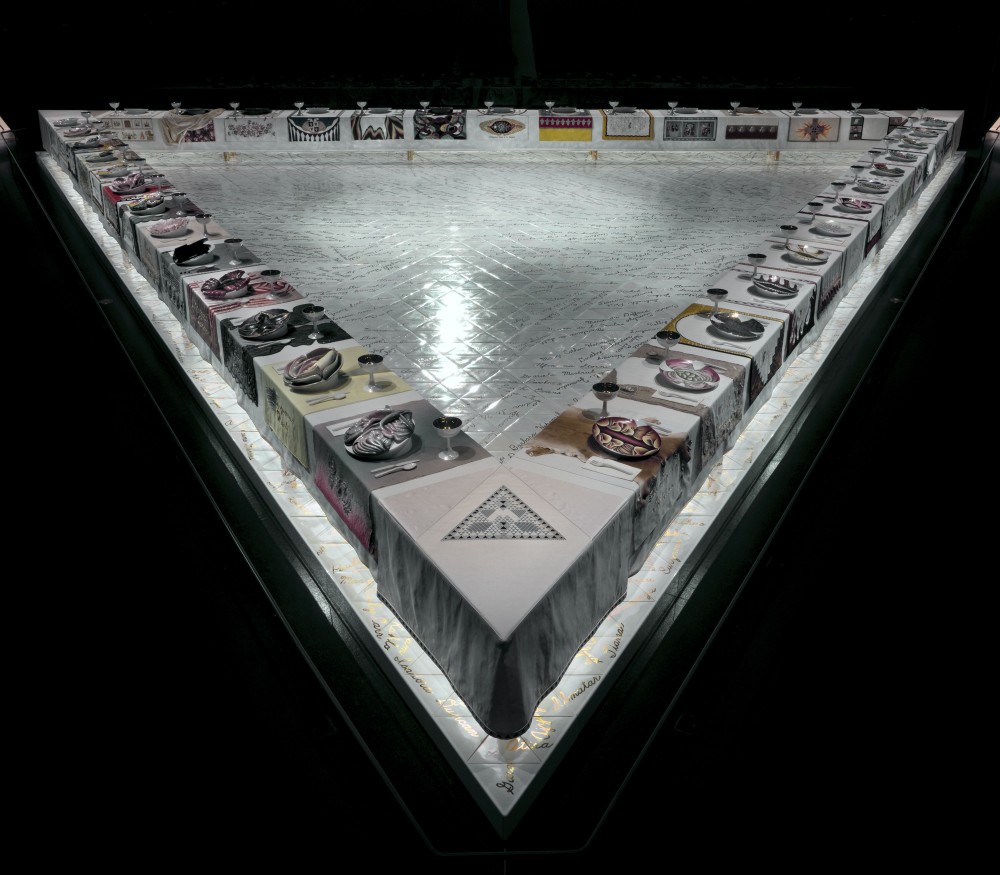

Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party (1974–79). Photography by Donald Woodman. Courtesy Brooklyn Museum.

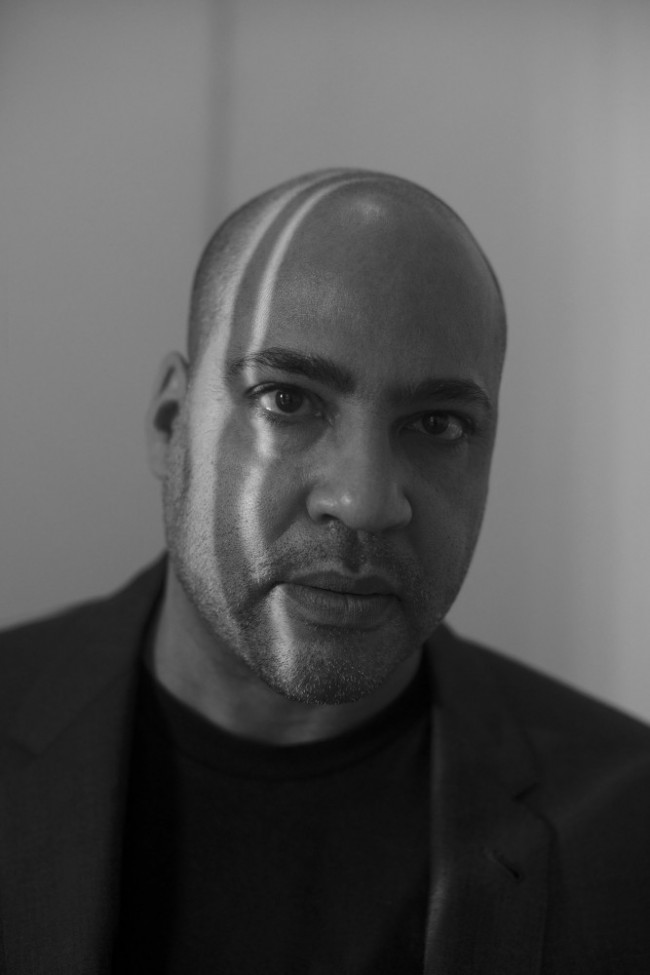

In the late 70s, Judy Chicago made a table with the middle cut out. Its gaping central void was indicative of women’s omission from history, something this seminal work titled The Dinner Party (1974–79) looked to impress. In 1974, Chicago began to conceive of this colossal, triangular, banqueting table, 48-foot-long on each side with places set for 39 eclipsed women who shaped Western civilization — the mythological and wise Sophia, the biblical Judith, the painterly Artemisia Gentileschi. The five year project was, Chicago said, a “reinterpretation of the last supper from the point of view of those who had done the cooking.”

The table’s form and scale was protest — at odds with the quotidian version of a table, and the scale at which women were used to working — in needle and thread, keepsake canvases. But it had another function too. It articulated Chicago’s grand ambitions of making space for and giving voice to thousands of women lost to the aeons, and to gather others, to participate in its formation. 400 volunteers — specialists in ceramic painting, casting, and needlework — gathered over the course of the project to make their mark, and then thousands flocked to see it — they still do — and thousands more crowd-funded its first US tour. The Dinner Party spoke to people on some level, and then they spoke to other people and we’re still talking now.

Michael Beitz's Avoid Conversation Dining Table (2011). Courtesy My Modern Met.

Any doubts Arendt had about humanity’s social aptitude should be crushed by Chicago’s table. It gathered people up; those sharp angles forming points of connection. Each place was set with a hand-cast china plate — painted vulva-like — and ceramic flatware, and chalice and embroidered napkin and beneath them needlework runners, and the relationship between plate and runner spoke of women’s connection with their environment. While under the table, 999 other women’s names were inscribed in gold on the hand-cast porcelain tile floor. Large banners above the entryways to the exhibition read: then all that divided them merged and like to like in all things. And there were other tables, out of sight — in archival photographs documenting these collaborators gathered around tables for “Thursday Night Potluck Dinner,” to eat and drink and discuss their joint endeavor.

The table was collaboration, communion, celebration, ritual, return. The scale, temporal quality — five years of labor and over five decades of display — and its displacement — Chicago struggled to find it a permanent home — speaks volumes about humanity. But also of hope. When it’s not out touring the world with Chicago and her crop of ultraviolet hair, the table resides now in the Brooklyn Museum.

If Chicago’s table was generative and social, the tables — and there are several — in Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1975) made around the same time, do something else. In the film, table is stage and alter, on which domestic duties take on a near sacrificial quality. Jeanne, the widowed housewife, is trapped in a life. This stagnation is enunciated by the presence of the table — kitchen, dining, dressing — it anchors the picture, or frames it, as carnal butcher’s block, preparatory zone for her schnitzel and for her sexual exploits, which occur off-screen. Until, that is, the film’s post-coital murder climax where we witness her in bed. This signals her renewal, her agency — a break of routine — and her awakening. So that the drawn-out circumspection of banal tasks and her solitude become radical.

Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). Courtesy British Film Institute.

Like her peer Martha Rosler with her Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), Akerman co-opted the thing women were given, as resistance, so that domestic objects became weapons. These women were autonomous in their practice, but forms of production are rarely solitary pursuits, and film a wholly collaborative effort. Highly visible and performative, the table is for Akerman and her peers, a centerpiece, from which to project out — a ripple effect. Those ripples reached Delphine Seyrig — Jeanne Dielman's lead actor. Up until that point, Seyrig had played ornamental parts in films such as Last Year at Marienbad (1961). But working with Akerman, Marguerite Duras and Ulrike Ottinger over the course of the 70s encouraged her to critically reflect on the role of women in film. Rather than a renouncement of the table, Akerman makes it a test site, psychiatrist’s couch and stage.

Much later, in 2015, she returns to the table in a film about her mother — a Polish immigrant and Auschwitz survivor — called No Home Movie. Capturing the essence of a tender, complicated relationship, this was Akerman’s roughly shot and cut journey towards and away from her mother’s table in Belgian with its long-faded palette of post-war vitality. From this central location, in person or via Skype, they unravel her mother’s story. It too is an awakening. And it too is a ripple. Around the table mother and daughter discuss the merits of potatoes served skinless, or not, and it evokes the potato peeler in Jeanne Dielman’s hands. In No Home Movie, we see the solidity of the table deteriorate through the pixelated screen of a computer, as Akerman calls in from a distance — in Oklahoma, New York, Israel — like the wandering Jew. And as her mother’s health deteriorates over the course of the film, the table shifts from beating heart to hollow chasm.

Other noteworthy tables include the table of friendship, labor, and ambition, in Doris Lessing’s novel The Golden Notebook (1962). Despite the book’s post-modern form, the thing I remember most of this four-part “kitchen sink tale” is the table and the two women — comrades in arms, friends — who gather there. The table in Leonora Carrington’s painting The Old Maids (1947), some years earlier, is equally meditative though iridescent gold and loaded with spiritual premonitions and childhood fairytales — an inversion of Lessing’s quotidian aesthetic. For this surrealist, the table steadies the composition, or rather, acts as a point of departure from which to make gendered domesticity appear uncanny. The work is saturated with signs — in moons and crows and glowing eggs — and spectral oddities. In Mexico, where the British-born painter spent most of her adult life, she gathered other women around her table — fellow artists and immigrants Remedios Varo and Kati Hornaborn. Together they staged parties, practiced forms of witchcraft and boiled herbal elixirs, illustrated in the shadowy Three Women around the Table (1951). For Carrington, alchemic transformation — human to bird, or bird to goddess — looked like freedom.

Leonora Carrington’s The Old Maids (1947). Courtesy Sainsbury Centre.

A mirage is when a sheet of ice or tar refracts particles like light, air, dust. And then the whole picture trembles and fades out.

The weirdness of this situation resembles a spiritualistic séance where a number of people gathered around a table might suddenly, through some magic trick, see the table vanish from their midst, so that two persons sitting opposite each other were no longer separated but also would be entirely unrelated to each other by anything tangible.

— Arendt

The table has faded out. Not yours, or mine perhaps, but ours.

Though this fading out is also an invitation — to start again.

The table turns from solid, to liquid, to air. It is now, in this pandemic, the act of keeping close through immaterial means. An acceleration of technology –– summoning more complex, sensory forms of communicating –– freeways of love and channels of generosity –– and with it, a reappraisal of our structural foundations — of home and work, online and offline in remote working and fibre-optical lifelines.

Let us shut our eyes and imagine other forms — variations of ourselves — somewhere loud and bright and warm. Drink it up. How might we summon the hum of those bodies, reach out and touch, in new forms — online, in parts, from afar? Because humans are social. And the table is generous, and willing. It is generative too, in its modes of transformation — dressed up as stage; a portal inwards and a projection out. An awakening.

If you turn a table on its side, you get a screen, which is also a kind of portal.

The screen with its impressions and connections is a table of sorts. The table (as screen) is bountiful. It is boundless too — a table without limits. It proposes new modes of making and sharing and thinking. We invent things from flour and water, or paper and paint and pixels and in doing so, spark another to assemble from the bare bones of their cupboards. And so on it goes.

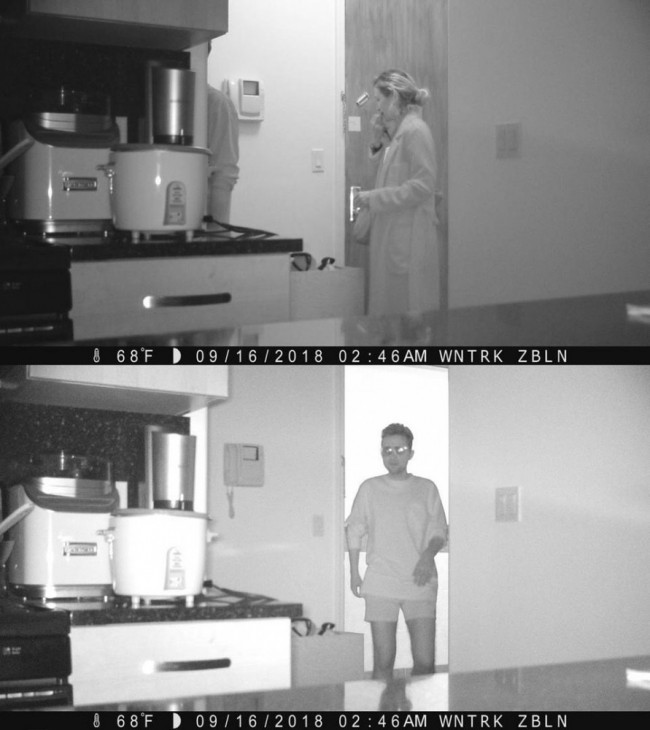

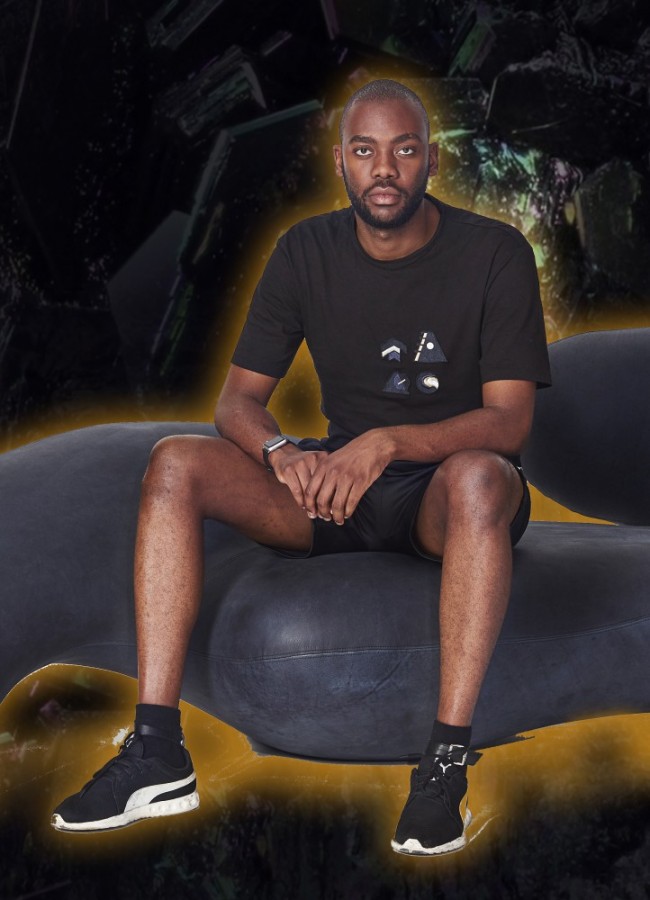

Naima Green's Yellow Jackets Collective (2018). Courtesy the artist.

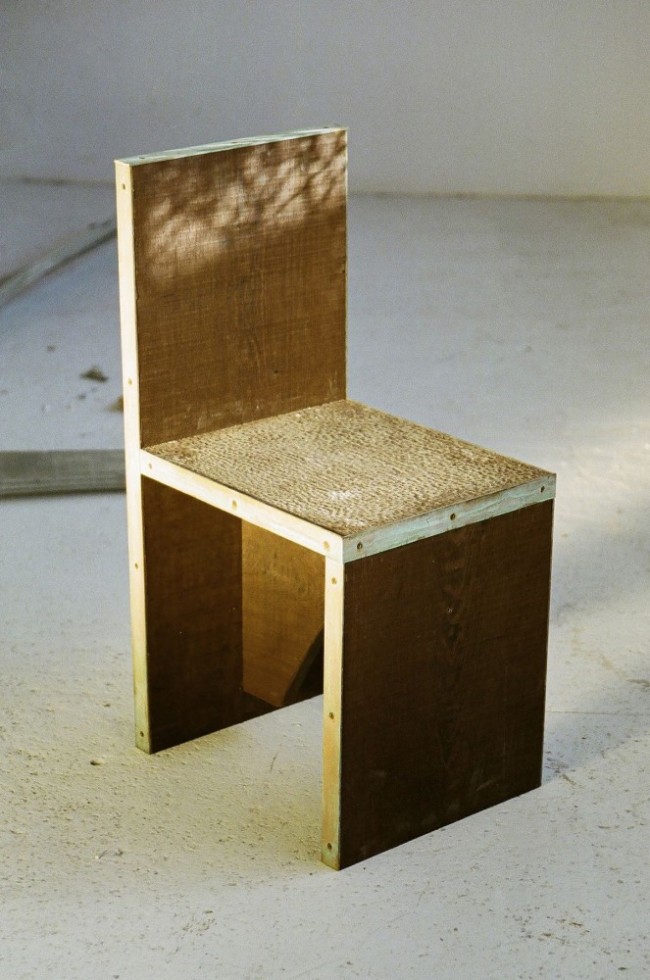

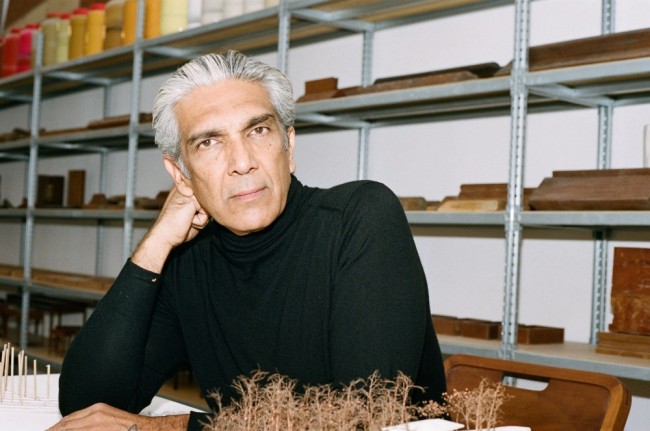

2 & a Possible, presented in 2019 by Miami’s Supplements Projects + ARTS.BLACK considered the table as “a microcosm of infrastructure” — what it is and what it could be. How it could proffer the intricacies and intimacies of relationships that blur work and life. Where it fell short in relation to gender and race. Through this project in Miami, artists GeoVanna Gonzalez and Najja Moon wanted to “challenge how an object can be absolved of expectations attached to gender” by blurring physical and ideological lines. Drawing on Naima Green’s Pur·suit deck of playing cards featuring queer womxn, trans, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming people, the pair fostered the fluidity of alchemic transformation for the 21st century. For Miami Art Week they planned to hold a spades tournament, where Green’s cards would be “accompanied with excessive amounts of shit talking at a table designed by Gonzalez and Moon.” I try and fail to find evidence that the event ever took place, and enjoy the ambiguity in its realization. The table was intended to be generative and social, in shades of Chicago’s — though its blurred lines — at the intersection of gender and sexuality and race — remind us how much further the conversation has come since the 70s. While inclusion of Naima Green’s Pur·suit deck whispered of ritualistic and occult practices historically forged by outsiders –– this once meant women, particularly “mad” women like Carrington but now, Green and Gonzalez and Moon remind us, might be those who are in between, who refuse categorization, welcomed at this table in reparative modes of practice. That the next installment of 2 & a Possible was made impossible in recent months, due to the pandemic, comes with its own cruel irony. And it is crueler still within the context of this notional table — of unrealized material projects.

Moon and Gonzalez responded to the enforced stasis of COVID-19 with The Aesthetics of Mobility — a YouTube series that they — life and work partners — have made from within the confines of their static truck-box home, itself the foundation of a bigger project called Living Life as Practice. Through short video installments that mostly take place around their self-realized table, the couple talk casually of the slippage between their daily lives and their practice — of “learning about ourselves and design through the process of living in this space.” So that perhaps this space is a kind of preparatory zone. Or another kind of test site.

Because a table is still a table even when it has wheels.

Modern American dining table. Courtesy Vermont Woods Studios.

It still stands for generation, communion, protest, ritual, shackles, stage, anchor, test site. But now it also stands for elasticity, transience, alchemy, blurring, a liminality, intimacy, openness, and acceleration –– this forward-motion on wheels. Our relationships with our screens, our interactions online began as solitary acts –– habitual in gaming and programming and chat rooms — but have been forced now into shared spaces that elicit some of the intimacy, the communion, and the openness of the table.

And these are versions of the protean table –– summoned, returned to, accelerated from –– that have the disorderly, glitchy feel of DIY. They become familiar as punctuation marks in time –– weekly, daily –– and expansive in their offering.

To touch something or someone is to make an impression — an elbow-polished top, the stroke of a soft cheek. How do we do this from afar? OUT OF TOUCH — a dialogue and artistic program curated by HERVISIONS founder Zaiba Jabbar at LUX in London — reconsiders intimacy during and beyond the pandemic, asking “what a meaningful language of touch might look like beyond the physical” in this new liminal, immaterial landscape. Jabbar suggests we might find auditory cues of kinship in a bird song or sensory potential in a quantum computer’s entanglement.

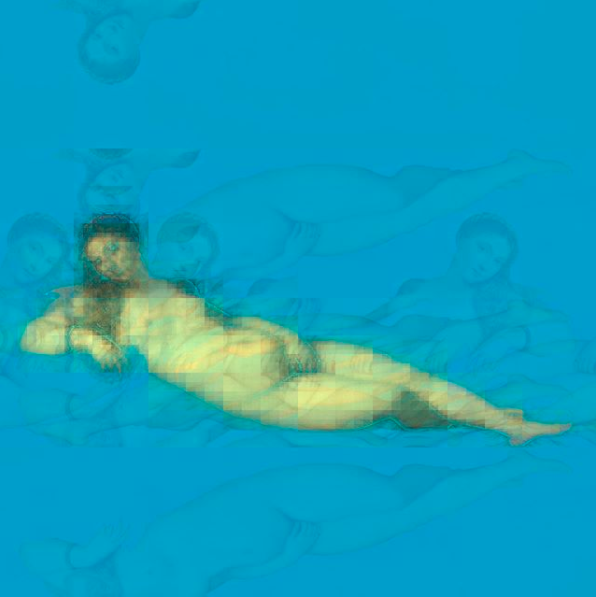

Featured artist Libby Heaney's reinterpretation of Titian’s Venus of Urbino for HERVISIONS (2020). Courtesy the artist.

Transmission is the act or process or passage of giving and receiving. And as such, Transmissions — a DIY TV show by Anne Duffau, Hana Noorali and Tai Shani — was a shared table. A late night table. One seen through bleary eyes. A dinner party table that spills over. People talk over each other until conversations are distorted and become entirely different things. Out of our collective isolation, Transmissions, streamed via Twitch, gathers and introduces us to one another and to weekly guests –– artists like Sophie Jung and writers like CAConrad. It is the stuff of chaotic late night parties where chance encounters happen and ideas are formed — amorphous and expanding, open and generous.

In this sense, it chimes with another Twitch-streamed communion, Radio Caroline, a word-of-mouth spare-bedroom radio show with the slogan Your Isolation Station. In the early evenings, we share our table with its host — writer and critic Jonathan P. Watts — to listen to grime punctuated with chamber music and birdwatching segments. Until we can return to each other’s tables, to pub tables, it will be these broadcasts and their chat rooms that impart daily handshakes, the squeeze of a shoulder, explosions of laughter. These projects won’t last forever, will likely come unstuck, or run their course, as is often the way with home-spun things –– but that makes room for something new, someone new, to join the table.

So here we are, gathered around the table, in remote lectures and intimate discussions and social circles in variable formations of togetherness, and in conversations from afar, the stream chat expelling heart-eyed emojis into Chicago’s shock of purple hair…then all that divided them merged, she said. Let us pull up a chair and sit. To be still, in the world, is a generative act. We do this until our hands twitch and we reach towards the table — laden with things — bountiful distractions — and fashion a white bird from a leaf of paper, or peel an orange. Then we look at each other across the table. And you speak or I speak. There is, of course, a question of who gets heard. But words vibrate, gestures are made. And on it goes. Who is to say whether we are left sated or hungry. That decision is ours alone.

But these are the ways of the table.

Text by Rose Higham-Stainton, a London-based writer interested in femininity, aesthetics, resistance, abundance, materiality, fashion, body, dress, adornment, and voids. Her work has been published in NOIT, MAP magazine, LOVE, Dazed, Jungle Magazine, V Magazine, CR Fashion Book, Rollacoaster, Pigeons&Peacocks, Lets Be Brief, and the East End Review.

Images courtesy the author unless otherwise noted.